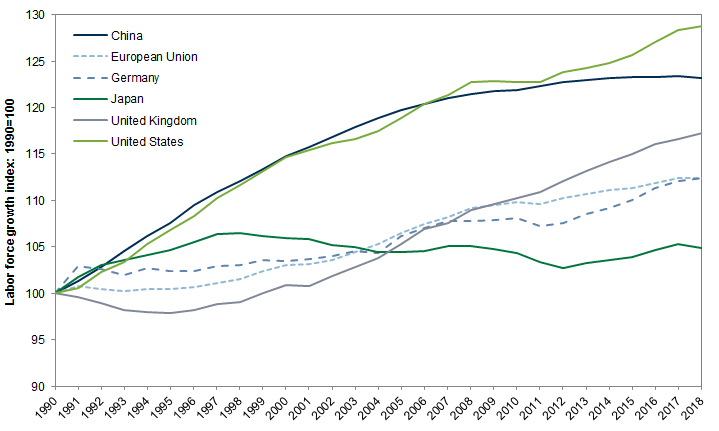

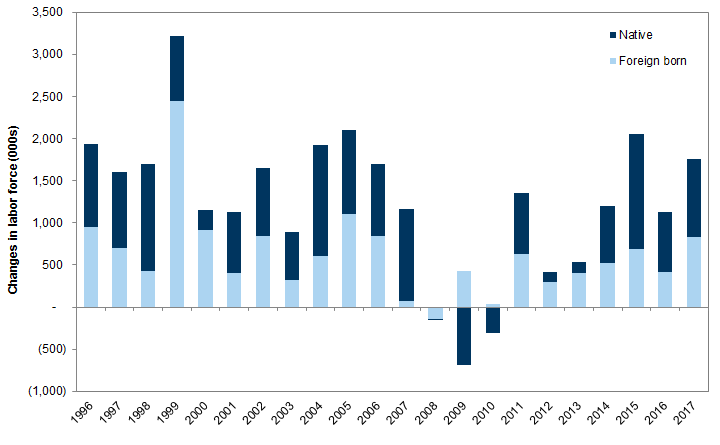

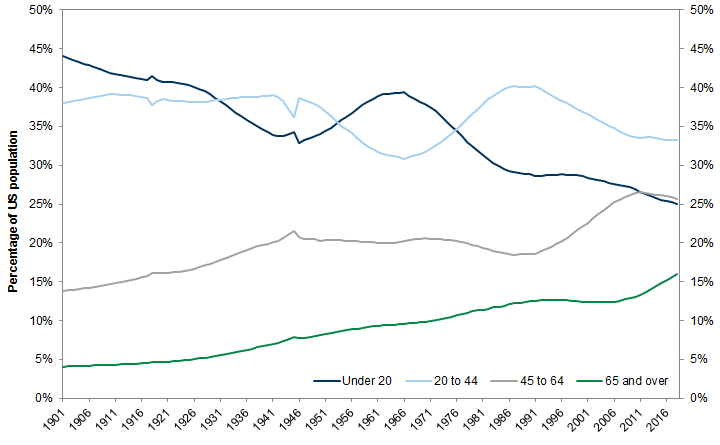

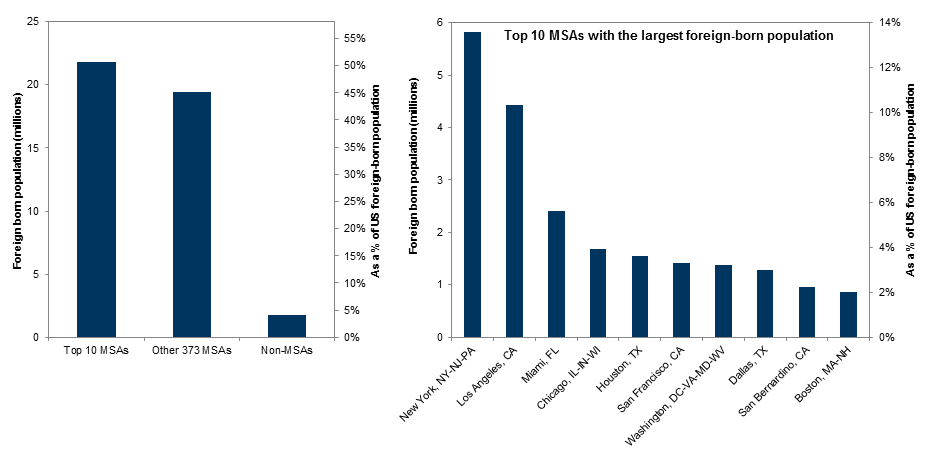

Long-term sustainable economic growth in any nation is linked to a growing and appropriately skilled labor force. Slowing labor force growth is a challenge faced by many nations. The United States has been a notable exception among the world's largest economies. Since 1990, the US labor force has grown by almost 30% and immigrants have accounted for about half of this net increase (Exhibit 1).

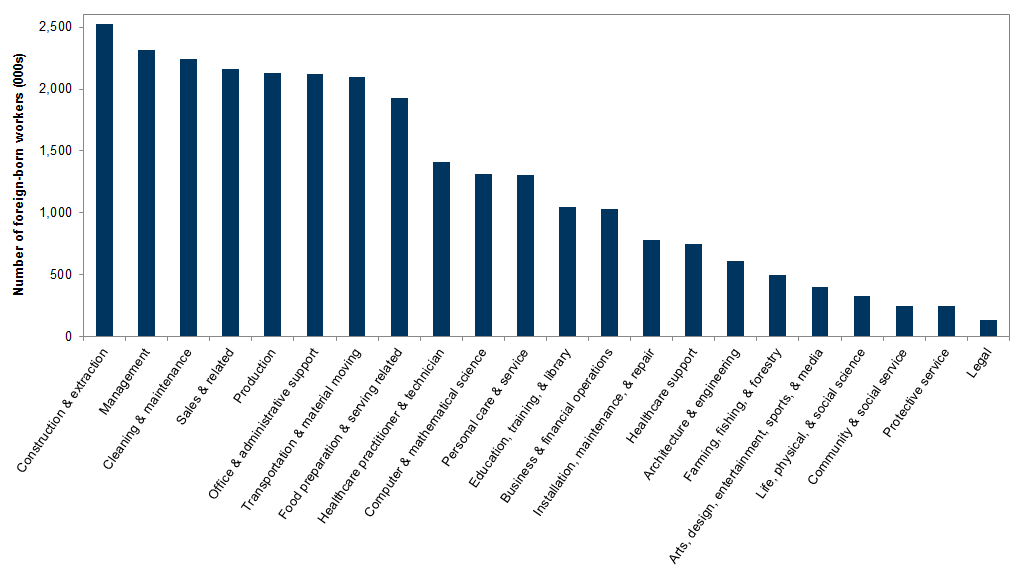

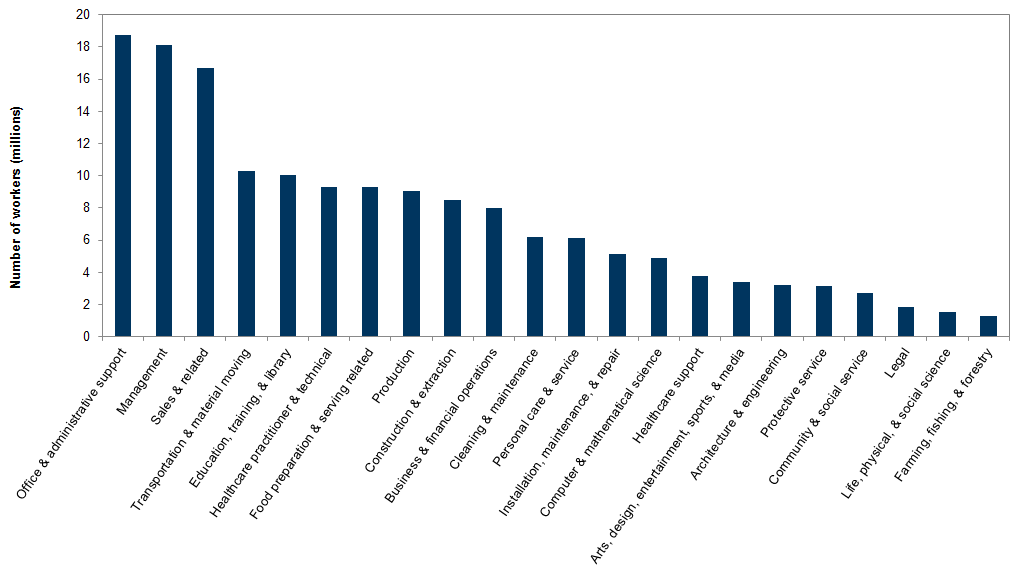

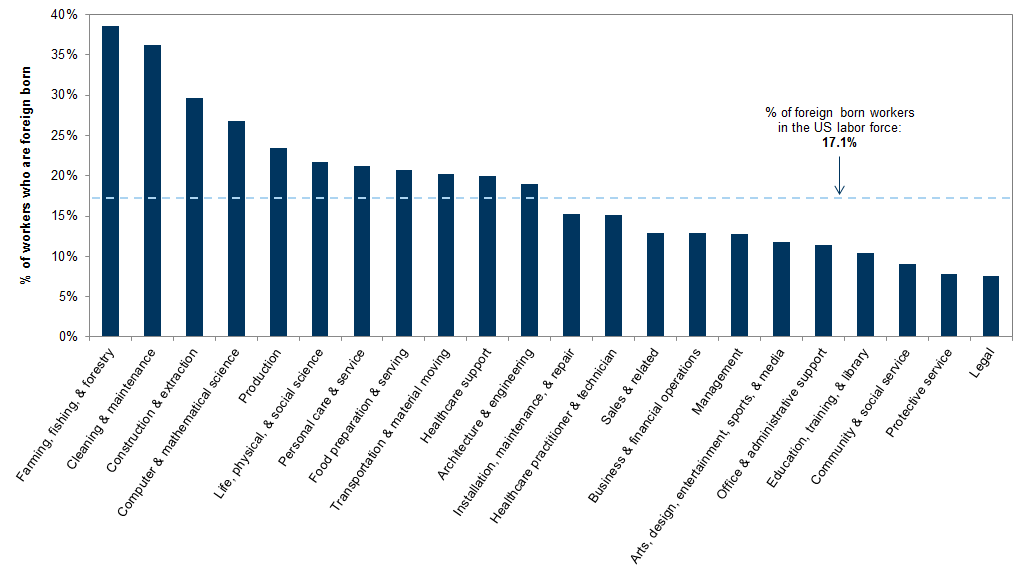

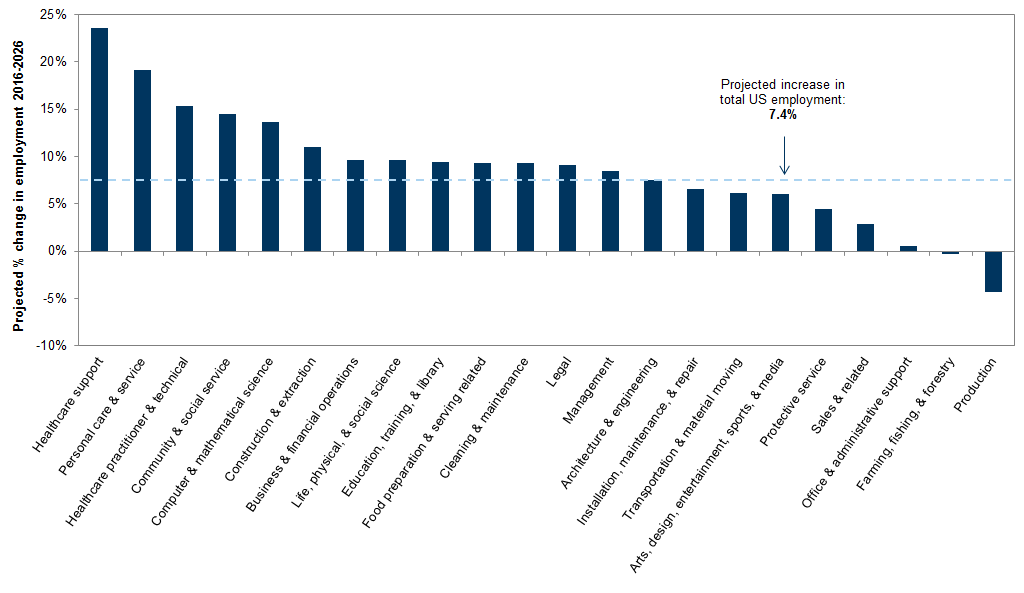

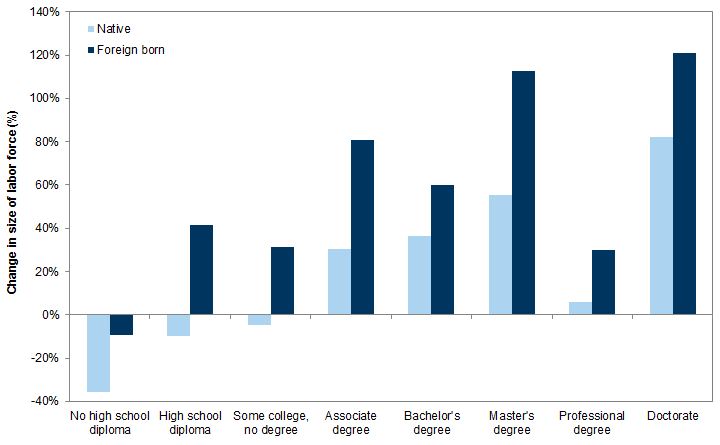

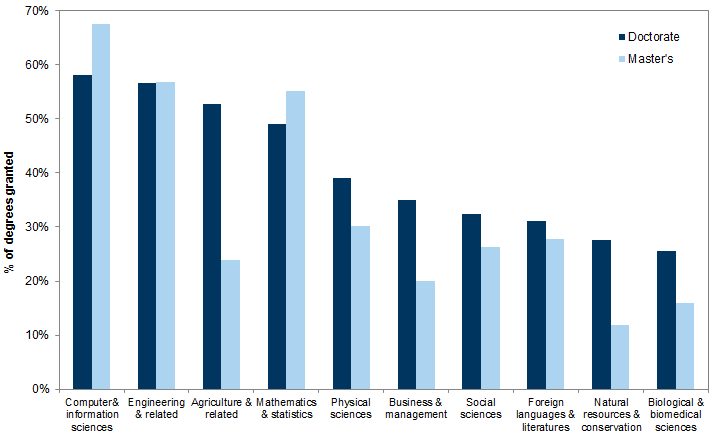

The US economy has undergone dramatic structural changes during this time. These include the shift from basic to more advanced manufacturing; the growth in service industries; and the explosion in industries tied to computer and information sciences. Immigrants comprise roughly 17% of the US workforce but are more heavily represented in highly skilled areas such as IT, mathematics, engineering, financial services and healthcare. In 2017, international students were awarded approximately 50% of the doctorate degrees granted by US universities in mathematics and 58% of those granted in IT and engineering. They were also awarded 67% of the master's degrees in IT and 56% of those in mathematics and engineering. These individuals have become a crucial source of talent for US companies (Exhibit 23).

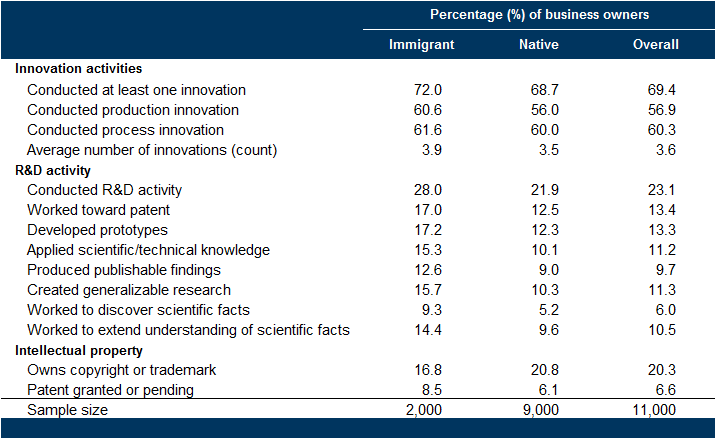

Approximately 45% of the companies in the Fortune 500 were founded by immigrants or their children. Over the last five years, more than half of the US Nobel laureates were born abroad. Since the 1930s, about one-third of all US Nobel laureates were immigrants.

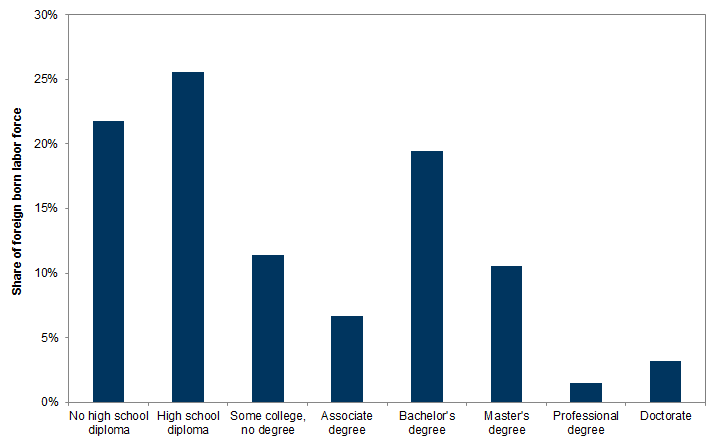

The experience of foreign-born workers in the US shows a stark bimodal distribution. While some excel, others are at the opposite end of the spectrum with regard to employment and income. Underlying factors relate to educational attainment, specific skills, facility with English and, in some cases, legal employment status. Upon entry in the workforce, immigrants have traditionally been concentrated in low-skilled occupations. More recently, occupations requiring high skills have seen the largest increases in foreign-born workers.

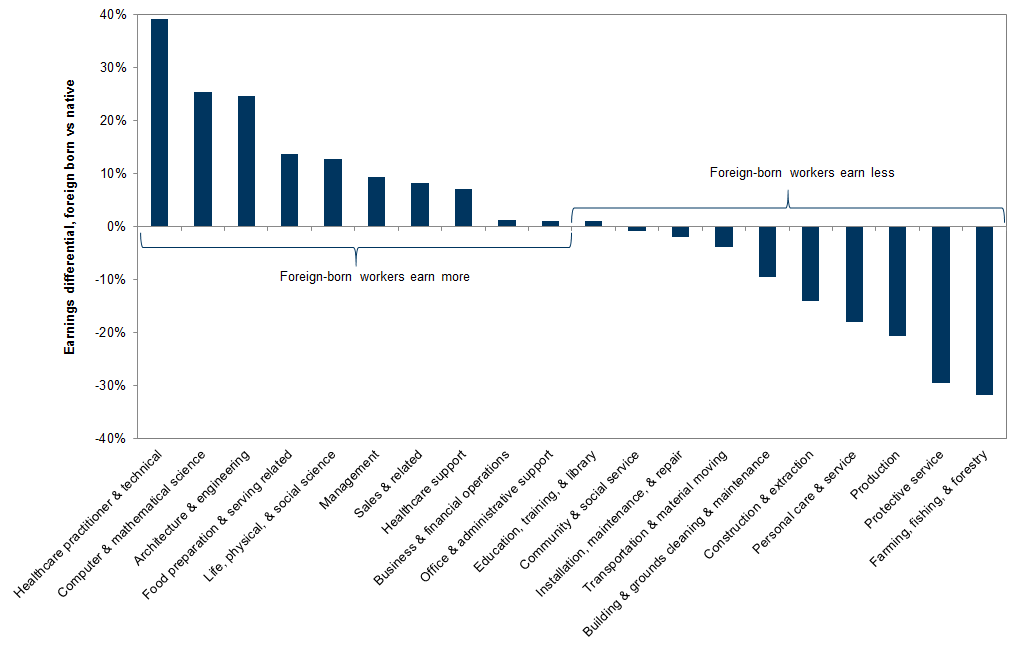

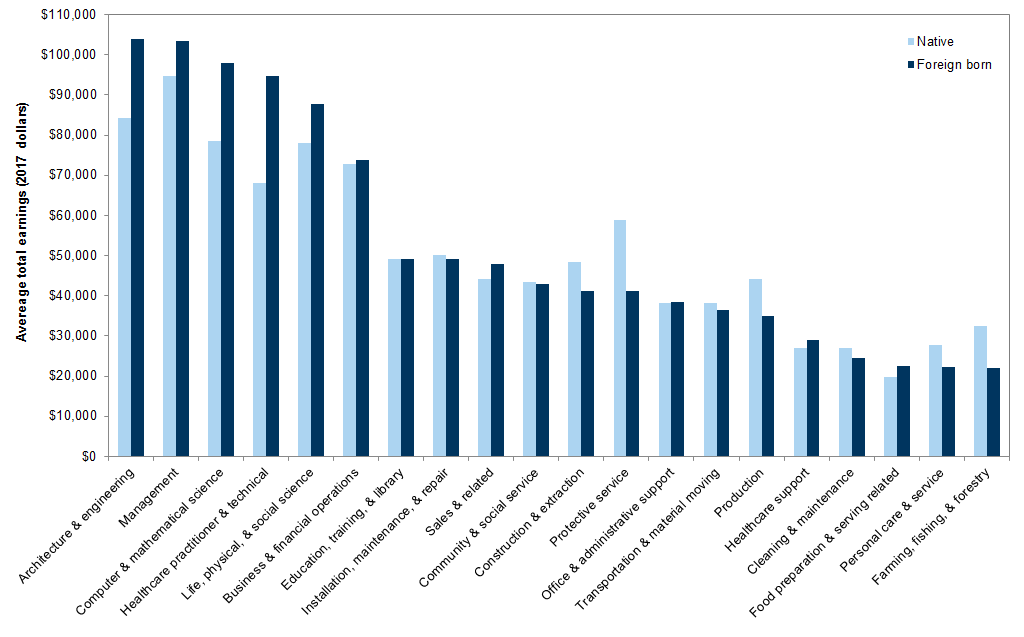

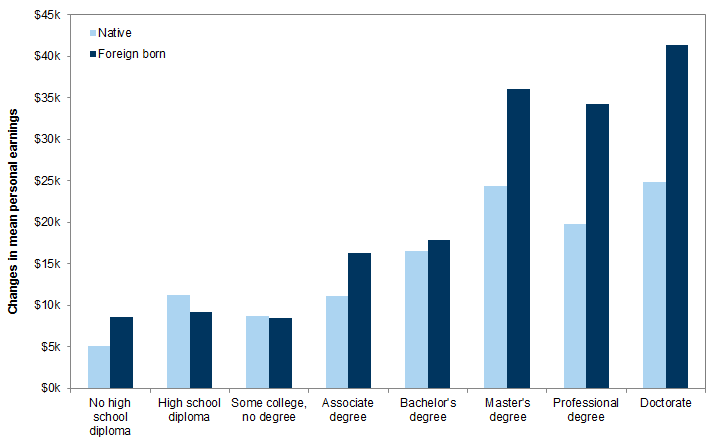

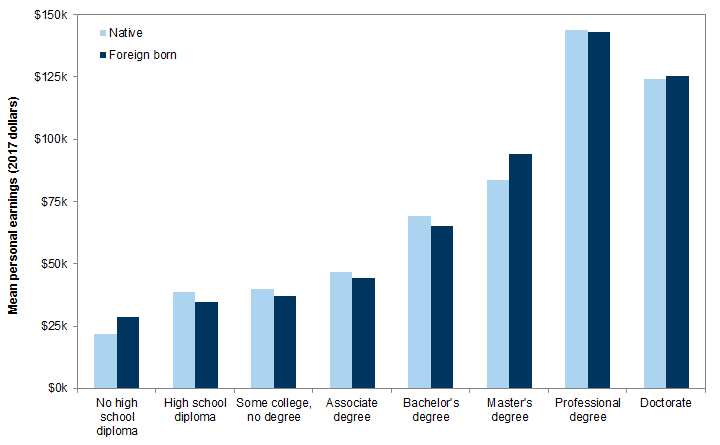

Foreign-born individuals comprise 41% of US workers who did not graduate from high school, although this number includes current high school students looking for work. In low-skilled occupations, foreign-born workers earn 15-30% less than their native counterparts, depending on occupation (Exhibit 10). Second-generation immigrants tend to perform far better economically than their parents due to higher levels of education, language proficiency and other factors (Exhibit 12).

Compared to native workers, highly educated foreign-born workers tend to have higher rates of unemployment and underemployment, particularly for those educated outside of the United States. But, field of study, not just the degree, determines employment opportunity and earnings. In some professions requiring advanced technical skills, foreign-born workers earn more than native workers due to stronger academic preparation and experience (Exhibit 10).

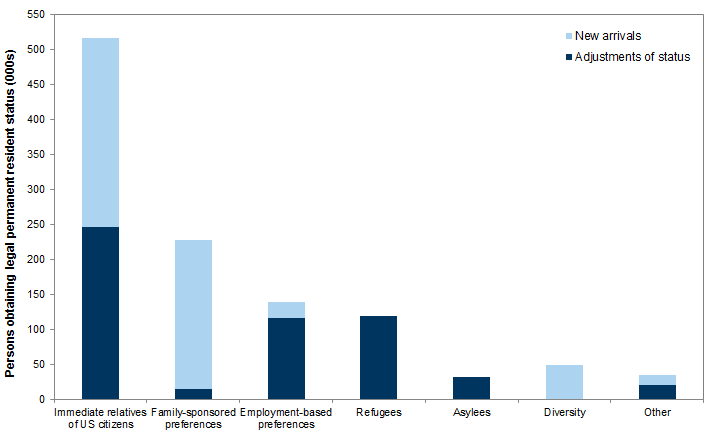

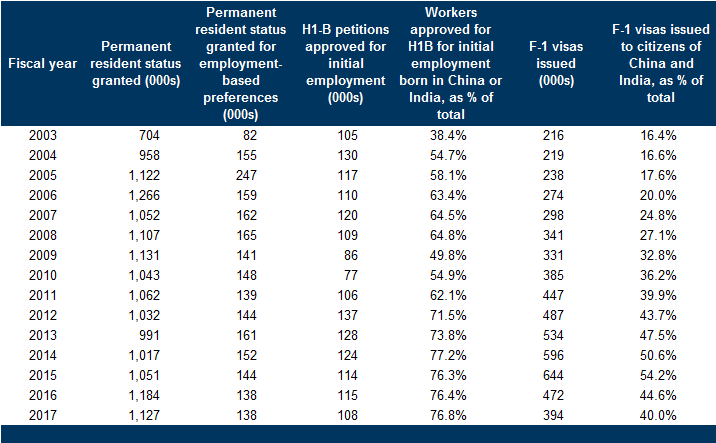

US immigration policy prioritizes family reunification. In FY 2017, 66% of individuals granted legal immigrant status were relatives of US citizens and permanent residents; 12% were granted status for employment reasons; and 11% were refugees. There have been declines in visas granted to international students and specialized workers since 2015. A large percentage of individuals granted these types of visas come from India and China. Finally, it is estimated that more than half of the newly undocumented population in the United States consists of people overstaying their otherwise legal visas and admissions.

Immigration and the US workforce

Introduction

Occupations held by immigrants: increasingly wide-ranging and professional

Exhibit 10: Earnings differential between foreign-born and native workers

Immigrants and educational attainment

Role of immigrants in innovation

Trends in employment-based immigration

- 1 ^ Germany, which experienced dramatic political strains after accepting a significant number of asylum seekers from Middle Eastern and North African countries during 2015-2018, may benefit from the resulting growth of its labor force over the coming years.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.