Why the narrative has shifted from inflation hedge to financial distress

Not all property types are created equal

Losses and contagion: Could this time be different?

CRE: Will this time be different?

Why last year’s friend has become this year’s foe

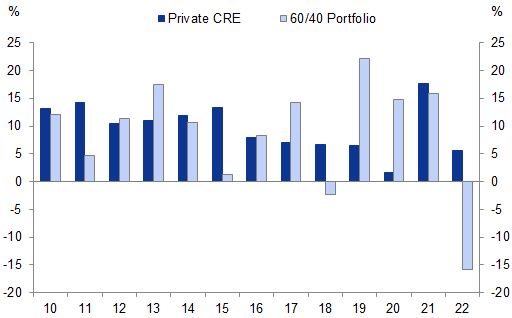

Exhibit 1: Private CRE vehicle outperformed the public fixed income and equity markets in 2022

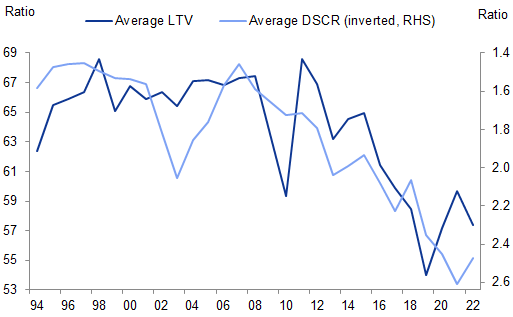

Exhibit 2: Leverage on CMBS has fallen over the past decade while debt coverage has improved

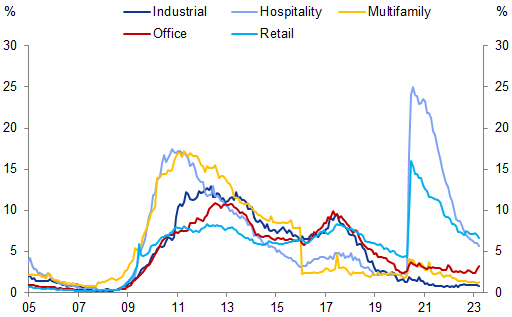

Exhibit 3: Delinquencies remain in benign territory

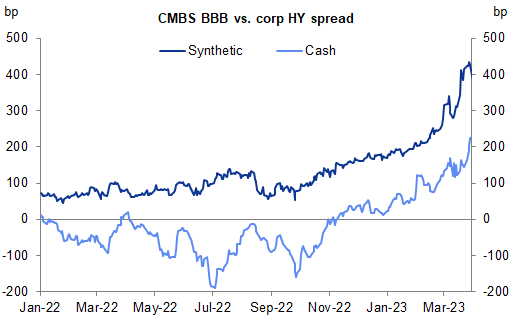

Exhibit 4: CMBS spreads have materially underperformed in recent weeks

Exhibit 5: The rapid run-up in CRE valuations over the past two years has many market participants questioning vulnerability to a higher for longer funding cost environment

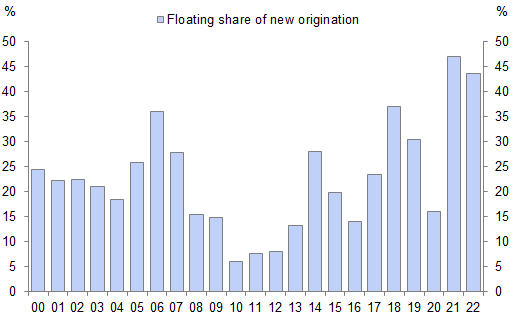

First, although greater guardrails have been put in place to contain systemic risk, CRE borrowers have increased their exposure to floating rate liabilities over the past few years. Using the universe of securitized commercial real estate loans in the CMBS market as a proxy, Exhibit 6 shows that the issuance of floating rate CRE loans has materially increased in recent years. While lenders often require floating rate loans to be paired with interest rate caps (tied to SOFR), borrowers are still exposed to higher rates up to the cap’s strike. Perhaps more importantly, the duration of the cap is generally shorter than the duration of the mortgage at full extension, which means that hedges would need to be reset at a higher cost.

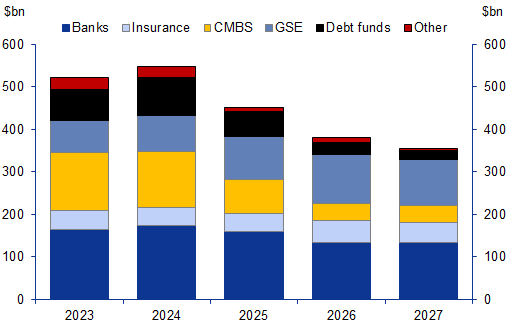

Second, in addition to the borrowers’ greater sensitivity to floating rate liabilities, near-term refinancing needs are also elevated. On our estimates, $1.07 trillion worth of mortgage loans will come due before year-end 2024 (Exhibit 7). Unlike residential mortgages, which tend to be fully amortizing, commercial mortgages generally have balloon maturities. This means that barring a dovish pivot by the Fed in upcoming quarters, many borrowers will likely have to refinance their fixed rate loans at higher rates. And while the recent significant widening of CMBS spreads may incentivize borrowers to extend their mortgages, such a move would come at the detriment of resetting the strike of their SOFR cap higher. Coupled with the ongoing pressure on NOI growth, this will likely diminish the ability and willingness of borrowers’ ability to refinance or extend loans, especially for beleaguered segments like mid- and low-tier Offices and brick-and-mortar Retail properties.

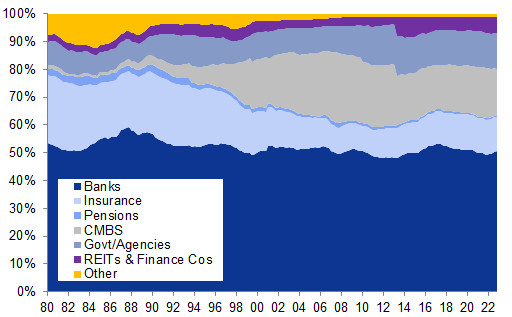

Third, financing conditions are likely to further tighten, going forward. Banks play an instrumental role in facilitating CRE transactions. Through the end of 2022, the amount outstanding of commercial mortgage loans in the US stood at $5.6 trillion. Over half of this stock sits directly on commercial bank balance sheets, with small banks capturing a much larger share than large banks (Exhibit 8). Small banks are particularly important to the CRE market: 70% of bank commercial mortgage holdings sit outside the top 25 largest banks (by assets). The potential for disruptions to US commercial real estate activity from a pullback in small bank credit availability is substantial, unaided by the fact that the segments most dependent on bank financing – offices and retail properties – are also facing the strongest risk of functional obsolescence. Outside of banks, the securitization market has also come under pressure, with the CMBS new issue pipeline drying up significantly. Year-to-date supply has declined materially vs. last year: -72% for conduit, -86% for single-asset/single-borrower, and -92% for CRE CLO.

Exhibit 6: The share of floating rate loans in CMBS portfolios has risen in recent years

Exhibit 7: Refinancing needs are elevated over the next two years

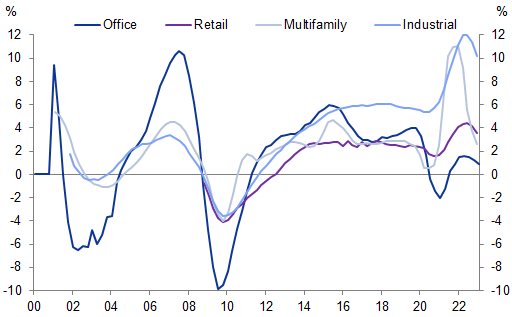

Not all properties are created equal

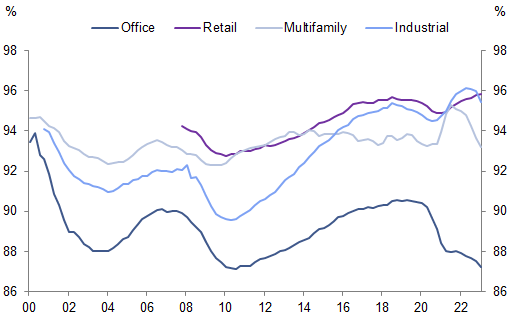

Exhibit 9: The decline in occupancy rates has been more pronounced for office vs. other types of properties

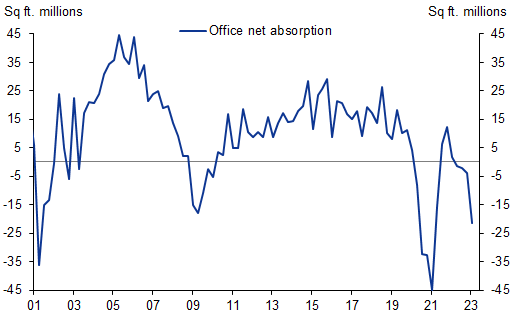

Exhibit 10: The trajectory of lease absorptions points to further spare capacity ahead for office properties

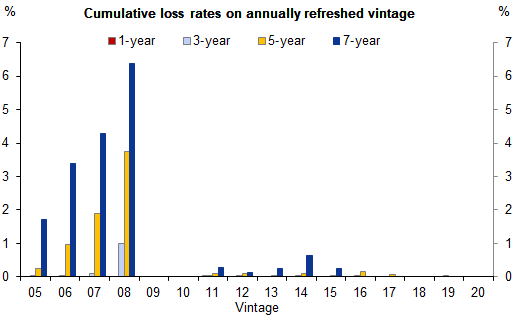

Losses: Typically, a slow burn but this time could be different

Exhibit 12: Losses on CRE loans are typically a slow-motion process

Exhibit 13: Losses in the 2007 and 2008 vintages were large but played over a long timeframe

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.