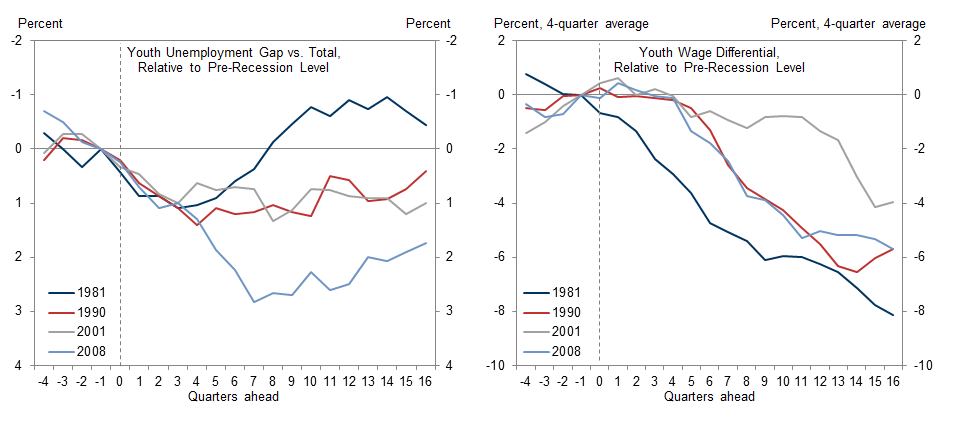

While the unemployment rate and other labor utilization measures signal an economy at full employment, wage growth has been weaker than expected recently, raising questions about the true degree of slack. To the extent that some pockets of excess slack remain, the cohort that came of age during the Great Recession would seem a natural place to find it, given the pronounced and long-lasting effects of recessions on young workers.

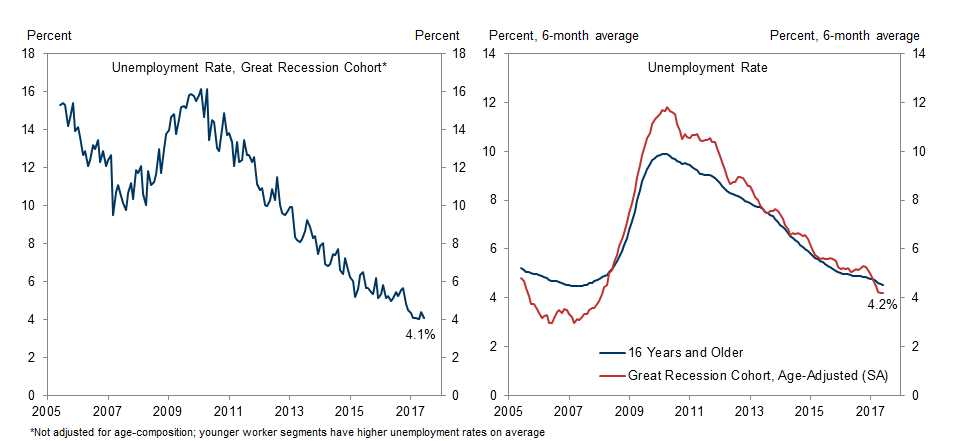

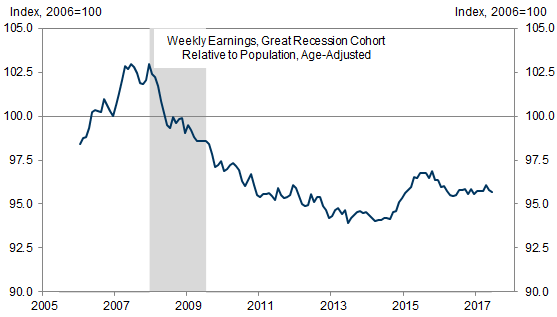

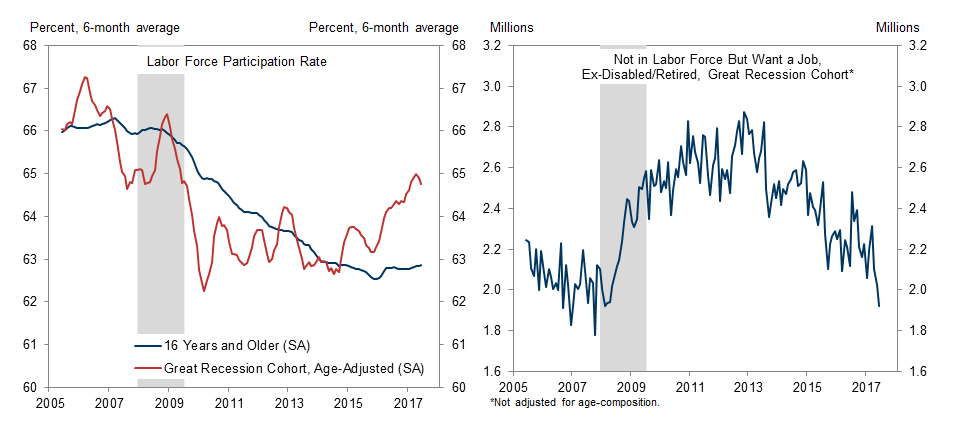

In today’s daily, we review the labor market experience of the cohort graduating college or beginning careers during or immediately after the recession. Unsurprisingly, unemployment rose sharply in this segment from 2007 and 2010. However, since then, jobless rates have improved dramatically on both an absolute and relative basis – particularly over the last year – and the unemployment rate in this cohort is now under the national average. Relative wages have also partially recovered, and broader measures of utilization suggest that minimal excess slack remains in this cohort.

- 1 ^ Specifically, we focus on the segment of the population born between September 1985 and August 1988, broadly consistent with the graduating classes of 2008, 2009, and 2010 (four-year colleges). While the recession ended in July 2009, the unemployment rate peaked in October 2009 and remained above 9% until October 2011, and we include the class of 2010 accordingly. In order to classify each age group into a cohort in a given month, we assume survey respondents were born in the middle of the year on average.

- 2 ^ Before calculating the cohort-level unemployment rate, we adjust each age-group’s jobless rate by adding back its 30-year-average gap versus the overall unemployment rate.

- 3 ^ To account for differences across age groups, we adjust average earnings in each age group by the 30-year-average proportional discount (or premium) versus national average earnings. While relative wages may have partially recovered, note that real incomes remain well below the level implied by their pre-crisis trend. Additionally, some of the recovery in wages reflects additional schooling that bore associated educational costs.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.