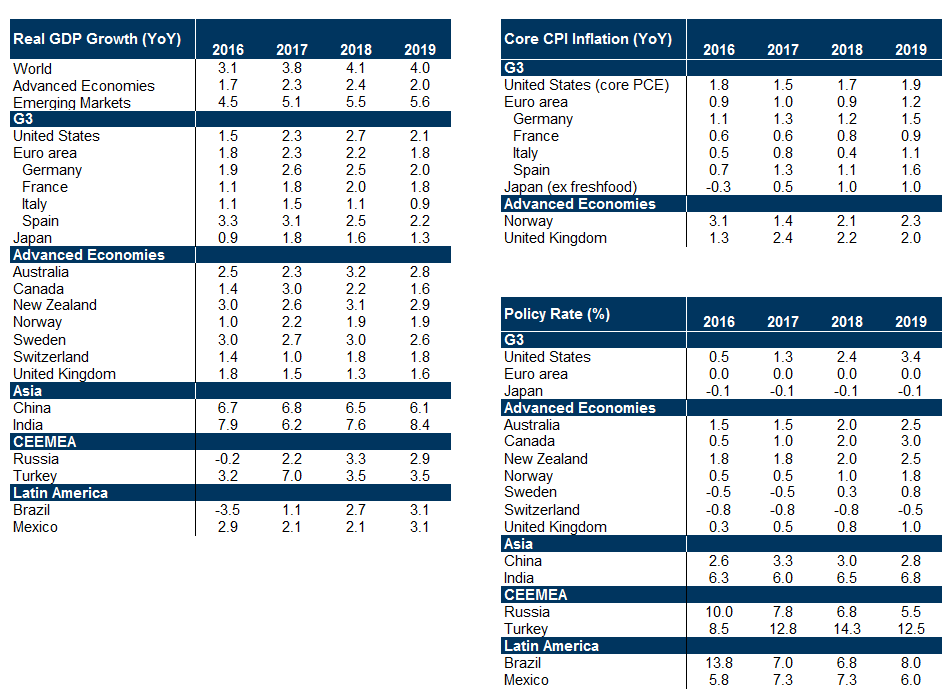

We expect strong global growth this year, given firm current momentum, easing financial conditions, and supportive fiscal policy. But high asset valuations and the prospect of labor market overheating suggest that the recent strength might be “too much of a good thing” further down the road.

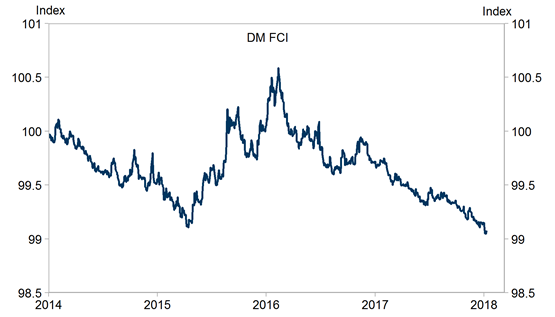

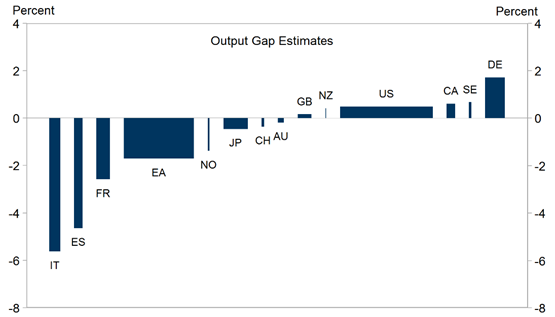

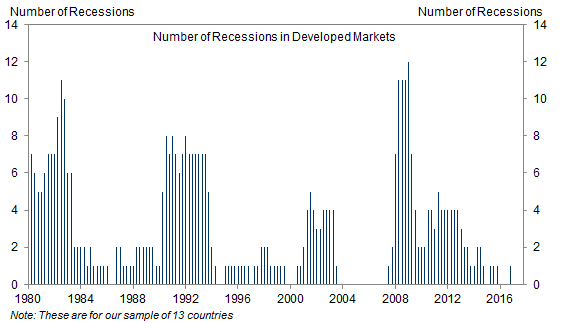

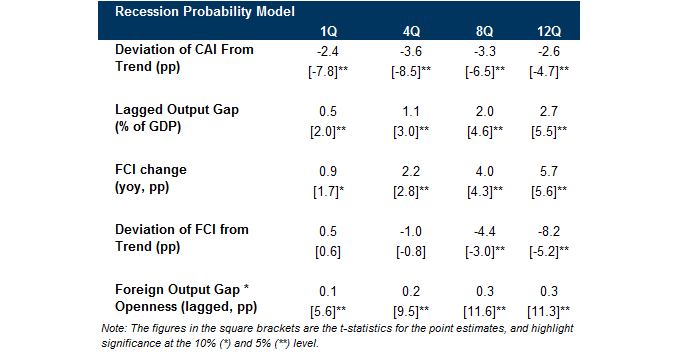

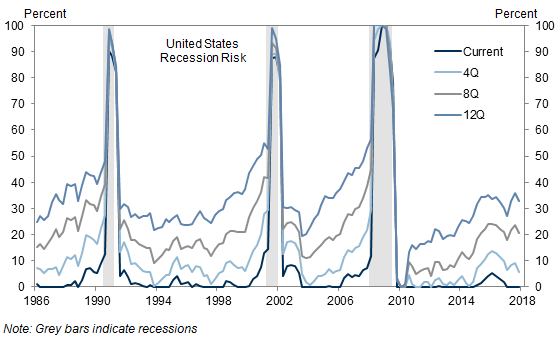

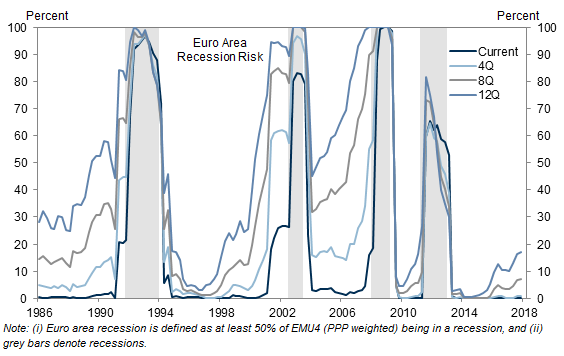

We revamp our cross-country recession model to gauge the risk of a downturn across major advanced economies with our proprietary indicators. At short horizons of less than a year, weak growth momentum (as measured with our CAIs) and tightening financial conditions are the best recession predictors. At longer horizons, output above potential, and unusually accommodative FCI levels signal recession risk.

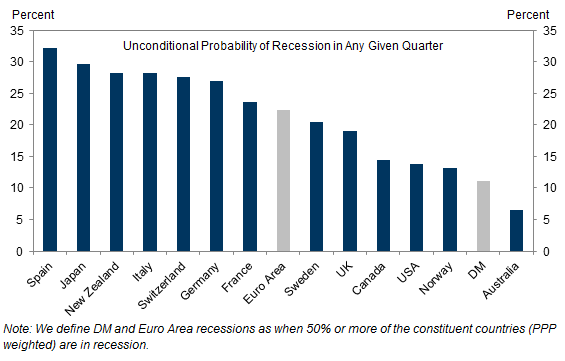

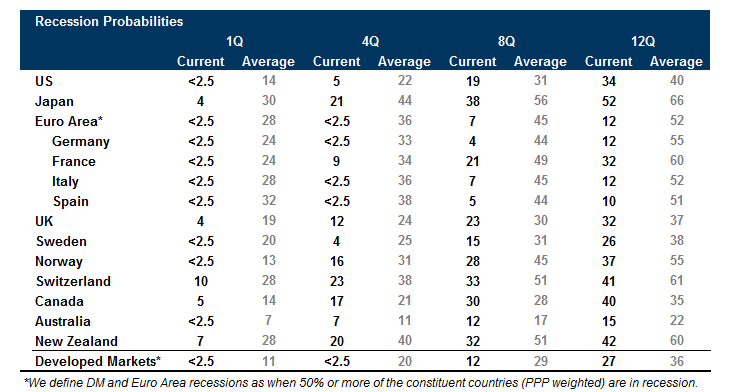

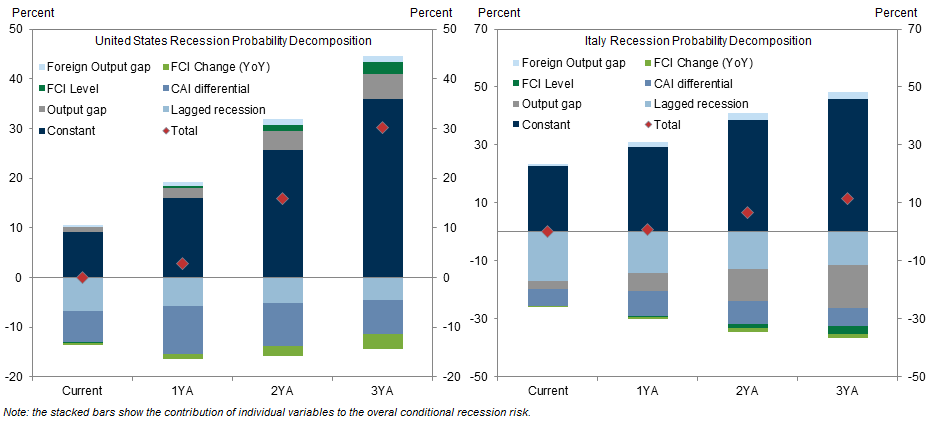

Our model suggests that near-term recession risk is low. The probability of a downturn is also below normal over the next 2-3 years, but has been rising steadily in economies that are seeing unusually easy financial conditions and tightening labor markets. These include the US, Germany, the UK and a number of smaller G10 economies (such as Canada and Sweden). Medium-term recession risk, in contrast, remains subdued in countries with remaining slack, including Spain, Italy and France.

Although our model is subject to a number of caveats, it confirms that we need to worry little about recession risk this year. But our analysis suggests that we should pay attention to measures of imbalances that signal rising recession risk further down the road. Our new recession model provides a tool to track these risks in real time.

A New Cross-Country Recession Model

Predictors of Recession

Recession Risk is Low…For Now

Nicholas Fawcett

Sven Jari Stehn

Manav Chaudhary

- 1 ^ For details of our earlier model, see Jan Hatzius, Sven Jari Stehn and David Mericle, “Doing the Numbers on DM Recession Risk,” Global Economics Analyst, February 5, 2016.

- 2 ^ For details of our potential growth estimates in DM economies, see Sven Jari Stehn, “From Demand to Supply: Our New G10 Output Gap Estimates,” Global Economics Analyst, November 5, 2017.

- 3 ^ The one-year alarm, for example, is equal to 0 in general, but switches to 1 four quarters before the start of a recession; it remains at 1 until the end of the recession episode. The two-year alarm switches to 1 eight quarters before the start of the recession, and so on.

- 4 ^ The new approach also eliminates the bias in panel probit models with fixed effects.

- 5 ^ If the country was already in recession in the previous quarter, then this raises substantially the probability of being in recession in the current quarter. We do not report this effect in the Exhibit, and focus instead on the most important drivers, assuming that the economy is not already in recession.

- 6 ^ These differences are explained by factors such as the trend rate of growth, and volatility of growth.

- 7 ^ Since we use a linear model, rather than one tailored to probabilities that lie between 0 and 1, it is possible that extreme readings of the explanatory variables lead to implied recession probabilities of less than 0 or greater than 1. In these circumstances the model may not capture the true effect of the drivers on the recession risk. Reassuringly, this happens relatively infrequently, so this problem is not severe in practice.

- 8 ^ If enough countries in an area enter into recession at once, then the area as a whole may be tipped into recession. We consider all the possible combinations of countries which would satisfy this requirement, and use our assessment of risk for each country, to evaluate the risk for the area as a whole.

- 9 ^ This is echoed by more formal comparisons of actual recessions to the predicted risk.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.