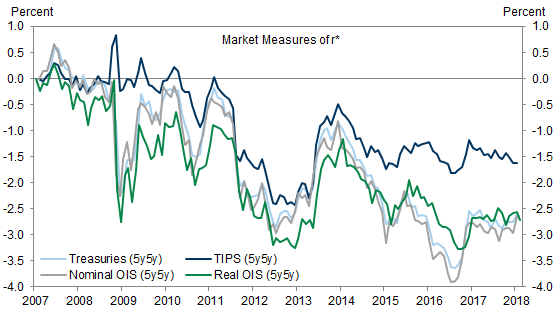

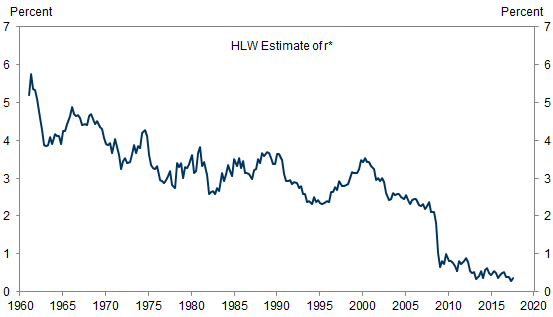

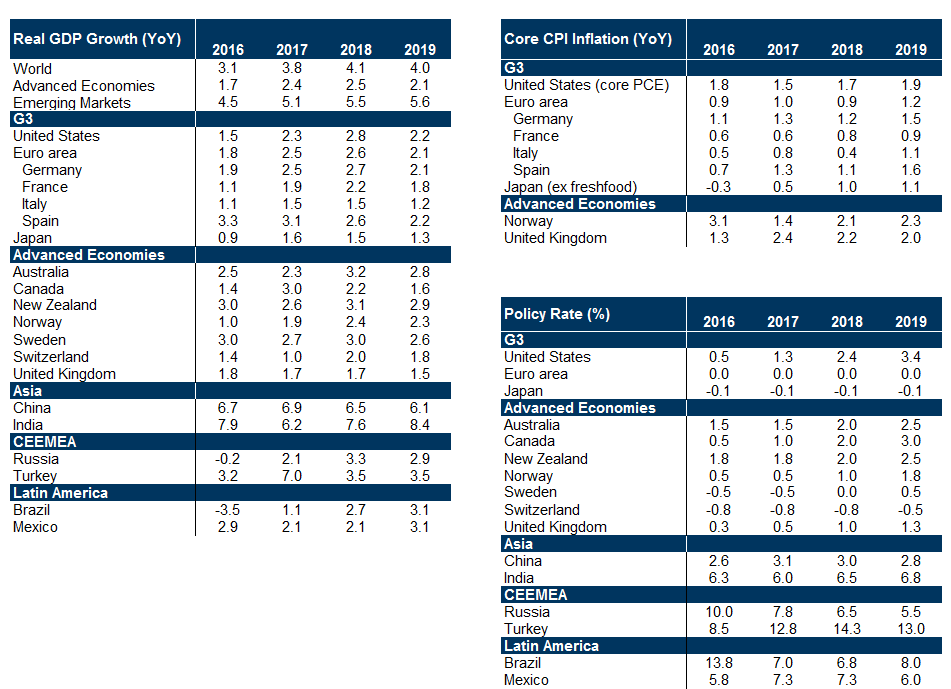

Although markets have recently upgraded their Fed view in light of stronger growth and inflation, longer-term expectations for the funds rate remain very low by historical standards. This downbeat assessment is consistent with the well-known model of Fed economists Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach and John Williams (HLW), which currently produces an estimate of just 0.3% for the real neutral funds rate, r*.

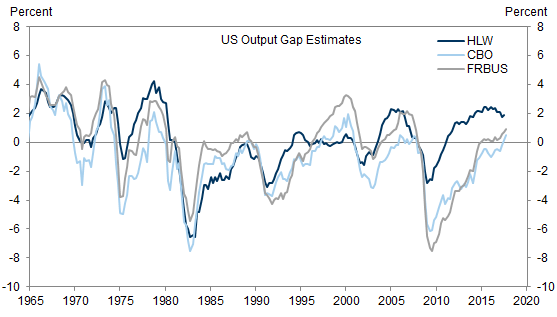

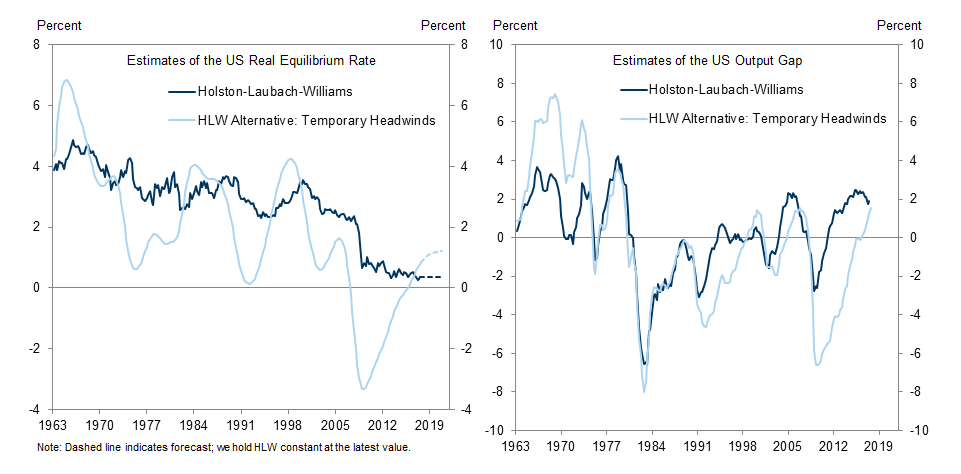

However, the HLW model is based on some strong assumptions. First, it backs out potential GDP from an “accelerationist” Phillips curve, which has worked poorly in the past decade, and it relies exclusively on GDP data to identify the economic cycle without an explicit role for labor market information. As a result, it produces an implausible estimate of the output gap, with the economy back to potential as early as 2011Q2.

Second, the HLW model does not explicitly allow for any transitory forces that might affect r*, such as disruptions in the housing and banking sector that were long-lasting but not permanent.

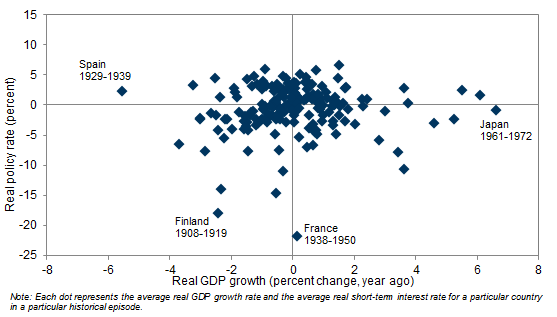

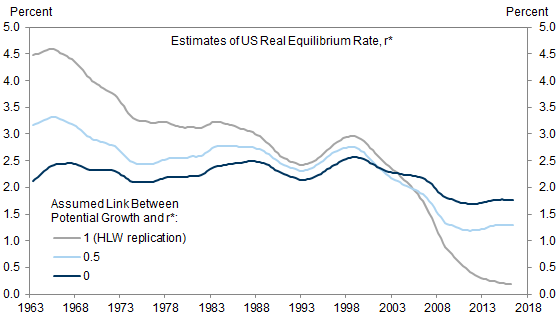

Third, the HLW model assumes that r* moves 1-for-1 with potential growth. However, long-term cross-country data show that this link is much weaker empirically than suggested by simple theoretical models.

Modifying these assumptions leads to very different results, even within an otherwise standard HLW model. If we use a Phillips curve with anchored inflation expectations, include labor market information to help identify the output gap, and allow for transitory headwinds, the r* estimate becomes ¾% now and is projected to rise to 1¼% over coming years. If we alternatively lower the impact of potential growth on r*, the estimate becomes 1¼%-1¾%.

This more upbeat view of r* is consistent with the recent performance of the economy. Despite 125bp of funds rate hikes and the beginning of Fed balance sheet adjustment, growth has accelerated sharply, the unemployment rate has fallen to very low levels, and inflation has started to firm. This is consistent with our view that the post-crisis weakness was more cyclical than secular.

Still More Cyclical than Secular

Questions about the HLW Model

Other Choices Lead to Higher r* Estimates

The r* Discussion and Economic Reality

Jan Hatzius

Sven Jari Stehn

- 1 ^ See Jan Hatzius and David Mericle, “More Cyclical than Secular,” US Economics Analyst, December 6, 2013; Jan Hatzius and Sven Jari Stehn, “The Rebound in the Equilibrium Funds Rate,” US Economics Analyst, May 29, 2015; Nicholas Fawcett, Sven Jari Stehn, and Jan Hatzius, “Depressed r* Narrative: On Shaky Ground,” Global Economics Analyst, November 29, 2016; and Sven Jari Stehn, “A More Optimistic View of the Equilibrium Funds Rate,” Global Economics Analyst, March 24, 2017.

- 2 ^ Estimates of the market’s view of r* are somewhat higher when the term premium is stripped from long-term yields instead of taking real distant forward rates. See David Mericle and Alex Demyanets, “The Market’s View of the Neutral and Terminal Rates,” US Daily, February 15, 2018.”

- 3 ^ See Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach and John Williams, “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants,” forthcoming in Journal of International Economics. The model is similar to the original paper by Thomas Laubach and John Williams, "Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest," Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 85, No. 4 (November 2003).

- 4 ^ This assumption implies that the model treats any changes in r* as permanent until the data prove otherwise.

- 5 ^ For details see Nicholas Fawcett, Jan Hatzius and Sven Jari Stehn, “The Depressed r* Narrative: On Shaky Ground,” Global Economics Analyst, November 29, 2016.

- 6 ^ This is an update of a model we first estimated in mid-2015. For details, see Sven Jari Stehn and Jan Hatzius, “The Rebound in the Equilibrium Funds Rate,” US Economics Analyst, May 29, 2015. We also include a measure of survey inflation expectations in the Phillips curve.

- 7 ^ Exhibit 6 shows our replications of the HLW estimates under different coefficients on potential growth using a two-sided filter to smooth the estimates.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.