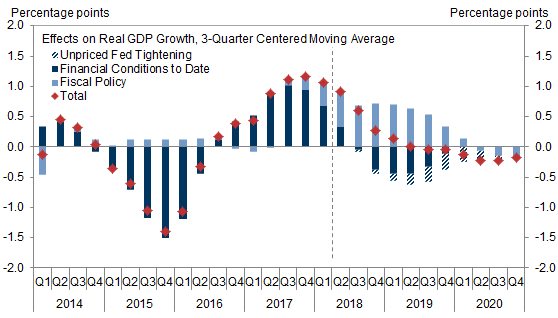

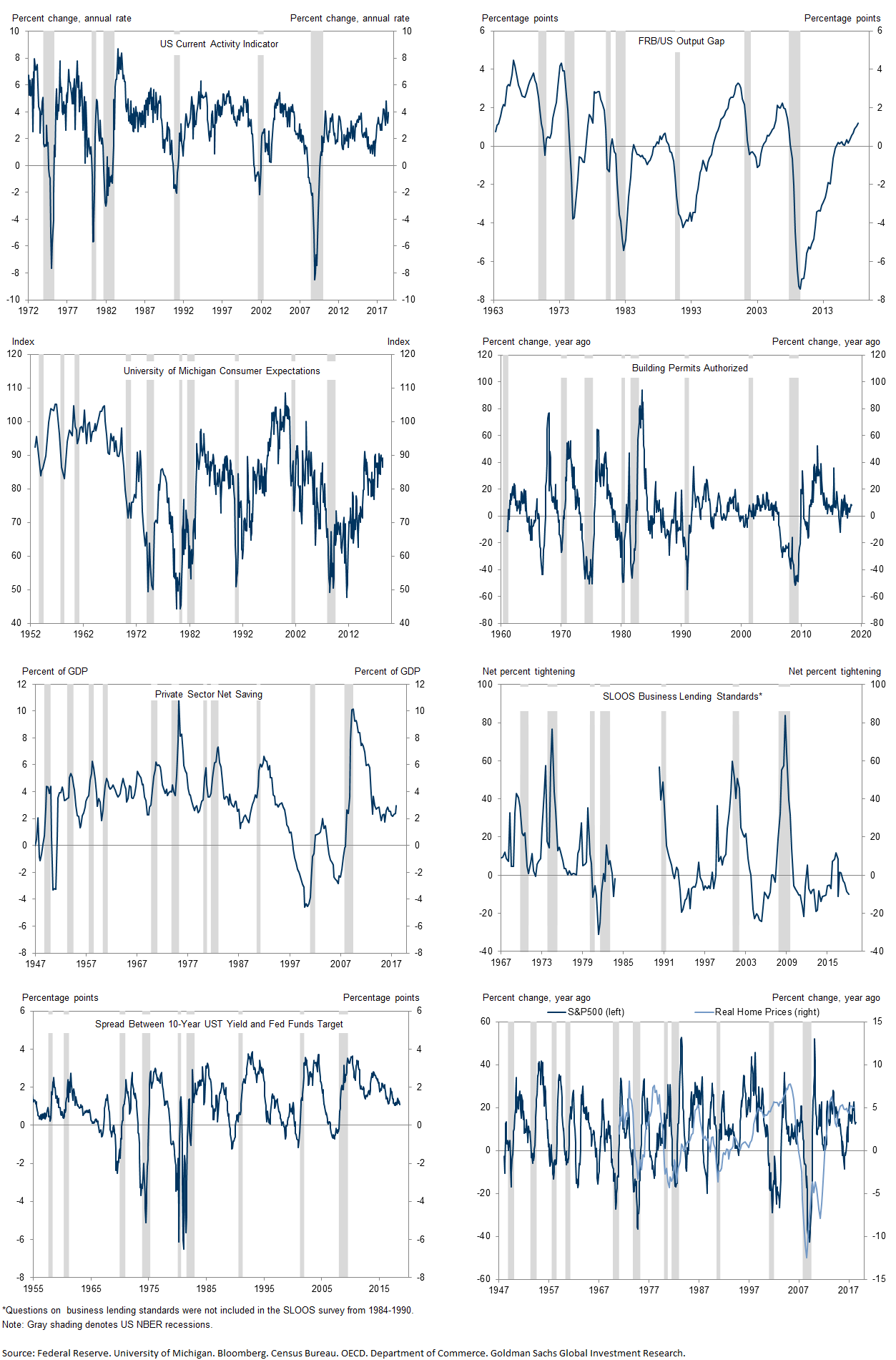

The expansion is now the second longest in US history and will become the longest if it survives another year. So far, the odds look good. But with monetary and eventually fiscal tightening on the agenda in the years ahead and concern about trade wars and spillovers from vulnerable foreign economies growing, markets have begun to grumble about the risks down the road.

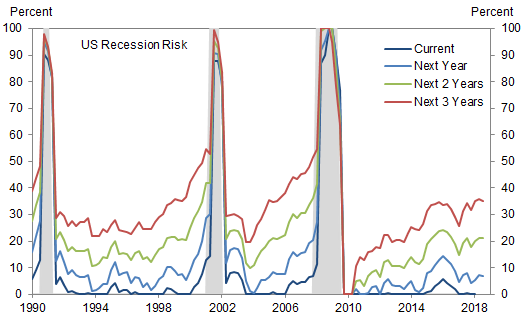

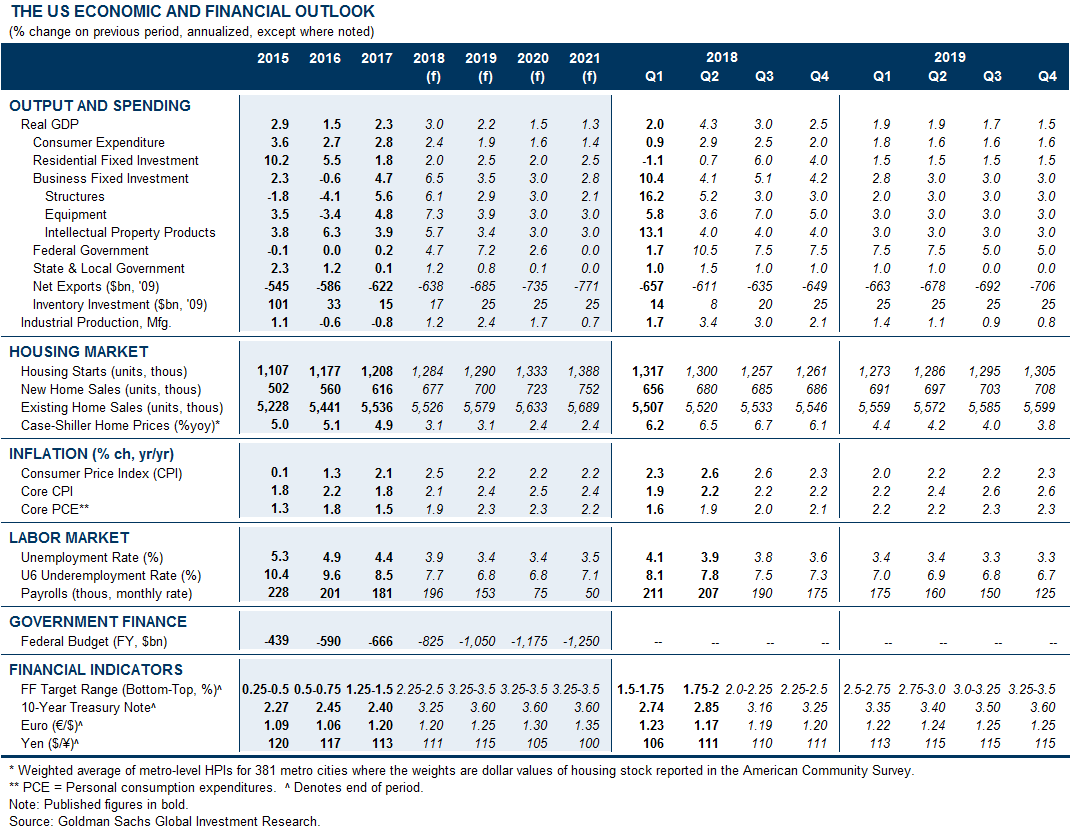

We see the popular thesis that a recession is coming in 2020 as a bit hasty. We do expect a passive fiscal tightening, tighter financial conditions, and supply constraints to leave growth ½pp below potential in 2020 at 1.25%. This implies greater risk of at least a technical recession in 2020, but it is not our base case.

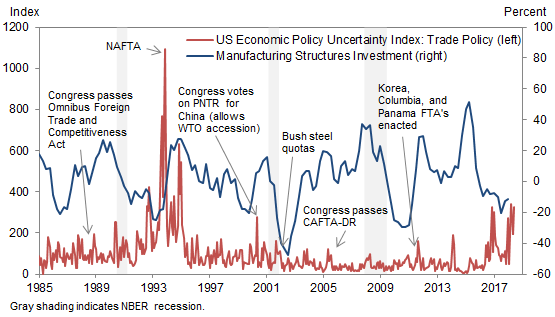

We see little evidence that the trade war has hurt US growth so far, and we are skeptical that trade policy uncertainty alone will weigh appreciably on aggregate investment spending. Even in the case of a larger trade war than we expect, both our global macro model and the relevant historical experience suggest that the direct economic effects would be limited.

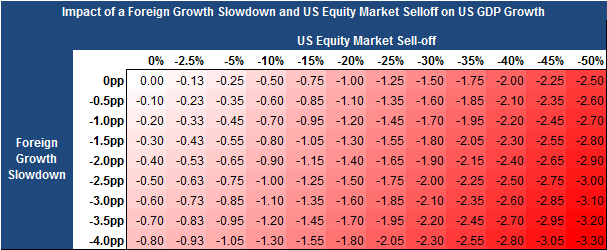

We likewise see little recession risk from purely economic spillovers from a potential foreign slowdown. But the greater synchronization of global equity markets raises the risk that the US could “import” a recession via financial channels in a more adverse scenario. Indeed, this is the most plausible channel through which a trade war or foreign slowdown could tip the US into recession.

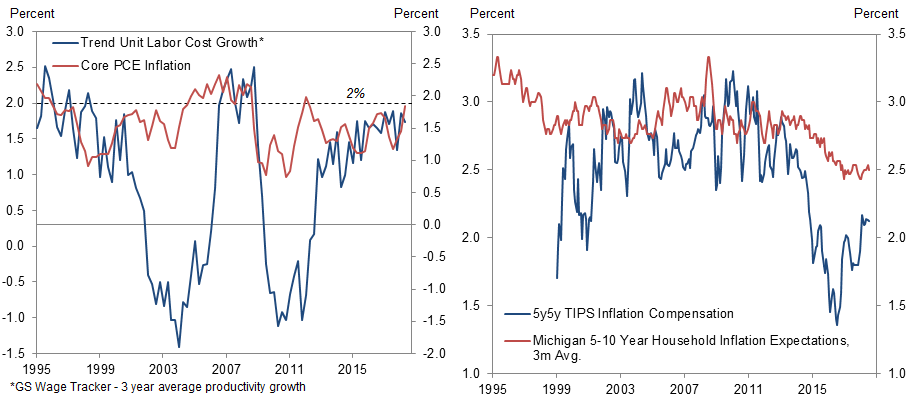

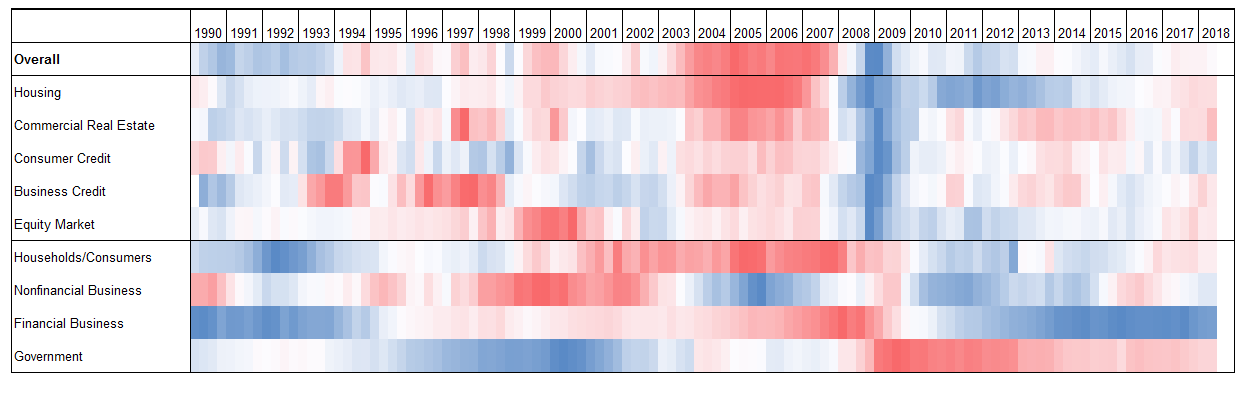

Turning to the usual suspects of US recessions, overheating and financial excess, we find little risk so far. Inflation, unit labor costs, and inflation expectations show no sign of overheating yet, but a historically tight labor market will pose risk. Our financial excess monitor also remains reassuring, with asset valuations mostly at moderate levels and few signs of private sector financial imbalances.

How long can the expansion last? The good news is that the lack of financial imbalances likely mitigates the overheating risk. But the bad news is that labor market overshoots have been very good predictors of US recession risk, and the current overshoot has a ways to go. The further it extends, the more difficult it will be to return the economy to a sustainable place. This implies an increasingly narrow runway for a soft landing.

Recession Risk Report: A Narrow Runway for a Soft Landing

Recession 2020?

Risks in Focus: The Trade War and Foreign Spillovers

Recession Risks: The Usual Suspects

Can the Expansion Last?

David Mericle

- 1 ^ While this might seem like a dramatic analogy, the impact of the Smoot-Hawley Act itself on the effective tariff rate—as opposed to the impact of the deflationary environment at the time—appears to be comparable in magnitude to the effect of the full set of White House proposals released so far. See David Mericle and Alec Phillips, “Trade Disputes: What Happens When You Break the Rules?” US Daily, 17 February 2017.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.