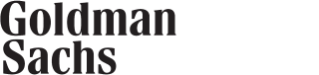

The historical correlation between yield curve inversion and recession is impressive. But what exactly is an inversion of, say, the 2s10s curve supposed to tell us? Roughly, an inversion indicates that the monetary policy stance is restrictive or is expected to become restrictive.

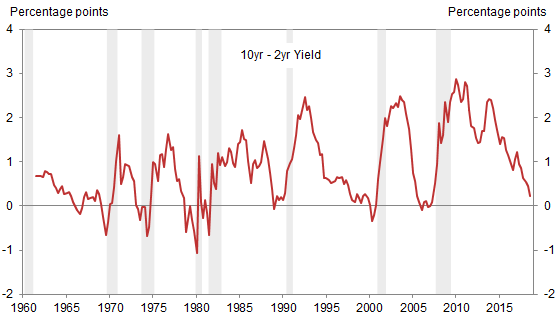

This signal has worked well historically because US recessions have tended to follow overheating that led to restrictive policy. But it raises two problems. First, it is inconsistent: the decline in the term premium has dramatically changed the signal about the restrictiveness of policy. Second, it is narrow: recessions do not have to be preceded by restrictive monetary policy.

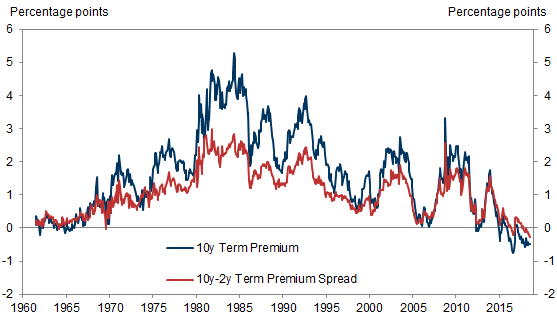

This does not mean that the yield curve is useless for assessing recession risk. In our view, the “wisdom of the crowd” embodied in the yield curve can provide useful input on two questions. First, the near-term forward spread provides a sense of the market’s view of the economic outlook. Second, the market’s view of neutral helps us judge how far into restrictive territory we have gone. At the moment, however, neither measure indicates heightened recession risk.

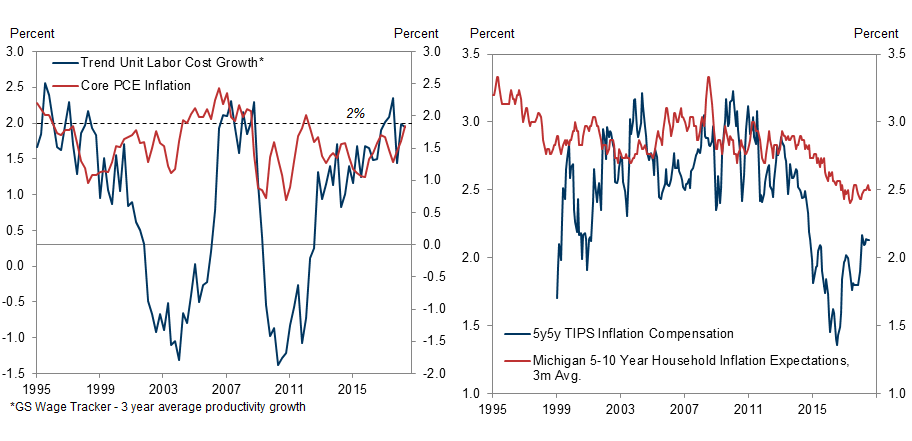

In gauging overheating risk, we think it is more straightforward to look directly at the economic data. We currently see moderate cause for concern: while price and wage pressures look contained for now, the US unemployment rate is headed to historically low levels.

The Yield Curve Does Not Indicate Elevated Recession Risk

- 1 ^ This is also true if we use model estimates of the neutral rate instead of market-implied estimates. The real fed funds rate (net of core PCE inflation) has exceeded the Holston-Laubach-Williams real neutral rate estimate in every recession since 1969, the first for which data are available.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.