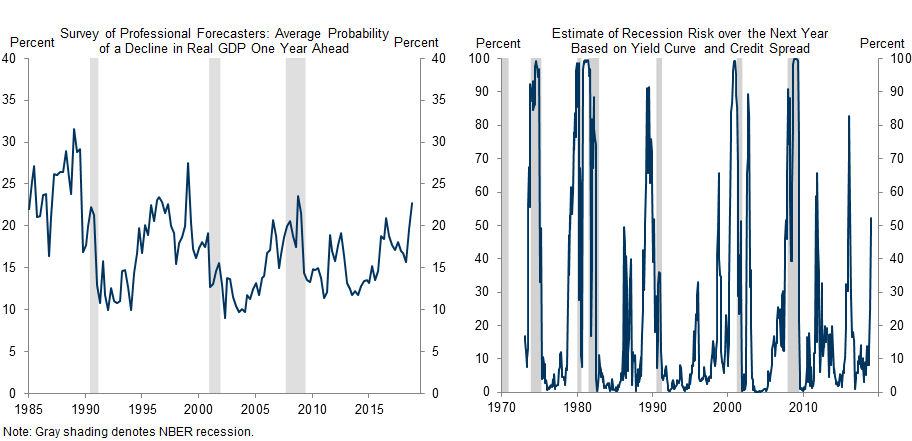

Investors have become more concerned about recession risk in recent months, as financial conditions have tightened and growth has slowed. On the surface, the worry is understandable, as soft landings are exceedingly rare in US history.

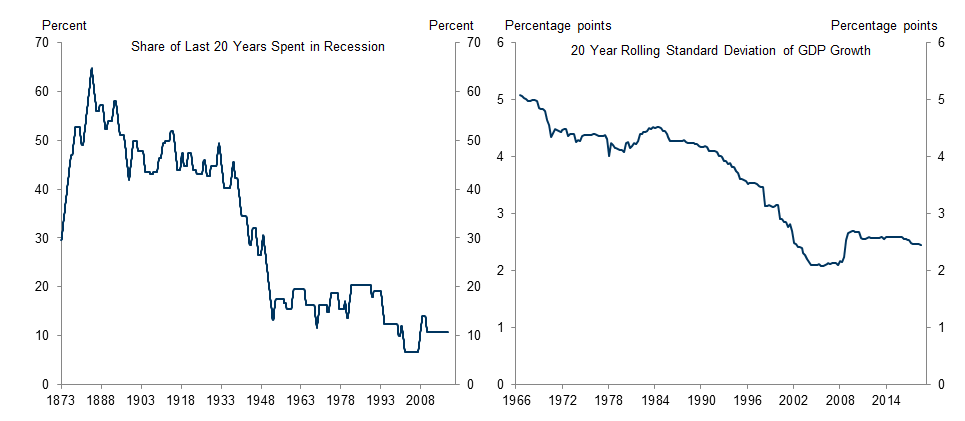

During the “Great Moderation” period before 2007, many economists were hopeful that various structural and policy changes had made the economy fundamentally less recession-prone. While this view took a serious hit in the crisis and the subsequent deep recession, we think many aspects of the Great Moderation are still intact, and some have even strengthened.

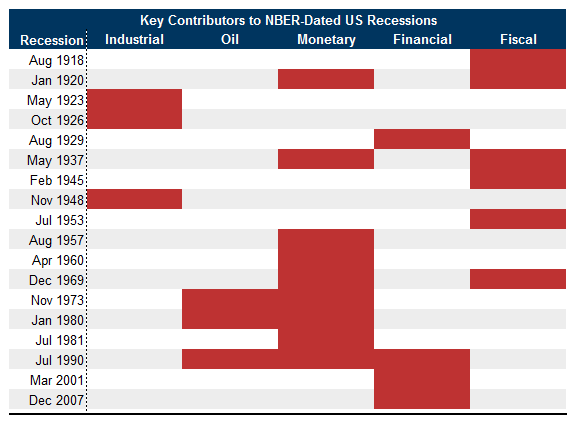

A review of the last century of US recessions highlights five major causes: industrial shocks and inventory imbalances; oil shocks; inflationary overheating that leads to aggressive rate hikes; financial imbalances and asset price crashes; and fiscal tightening.

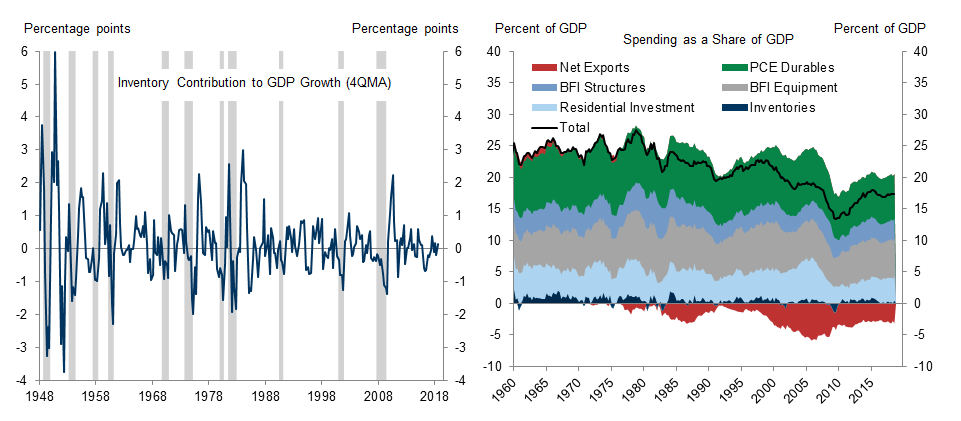

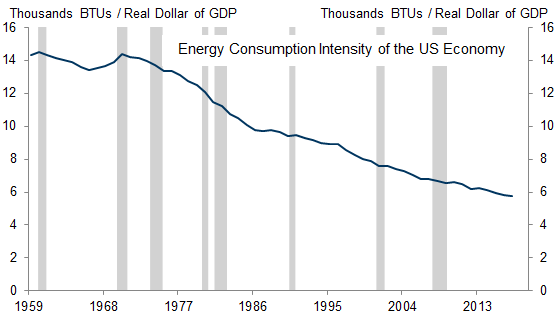

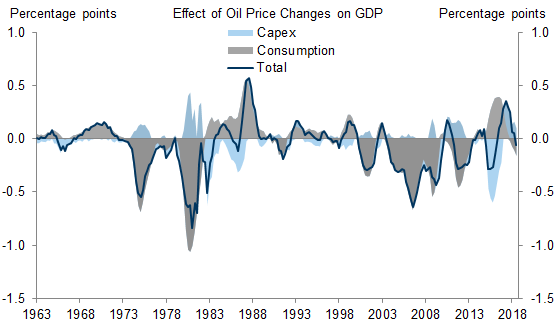

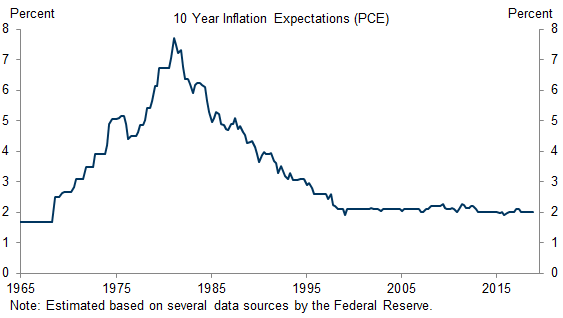

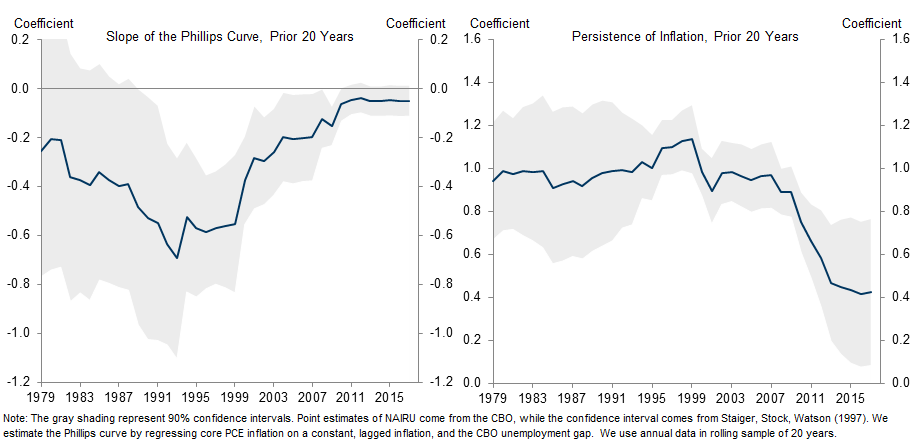

The first three causes of recession have become structurally less threatening, in our view. Better inventory management and the shrinking output share of the most cyclical sectors have reduced the impact of industrial fluctuations. The decline in the economy’s energy intensity and the rise of shale have reduced the impact of oil price shocks. And better monetary policy has led to a flatter and more anchored Phillips curve, reducing the risk of inflationary overheating.

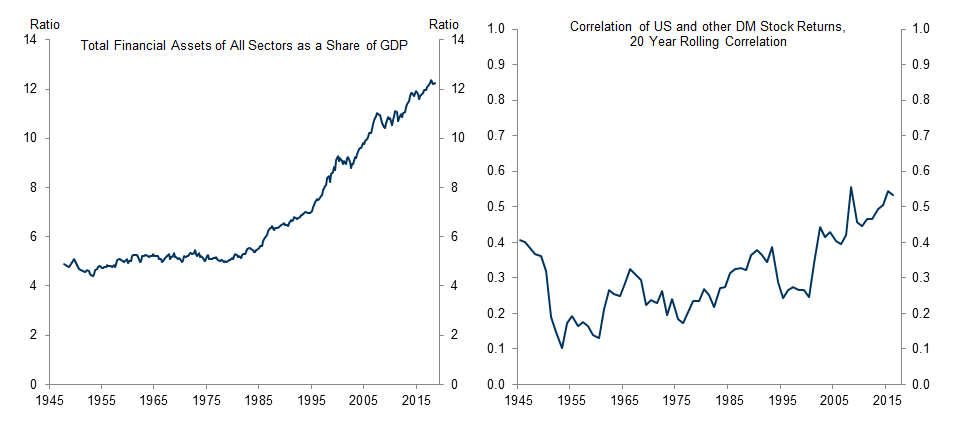

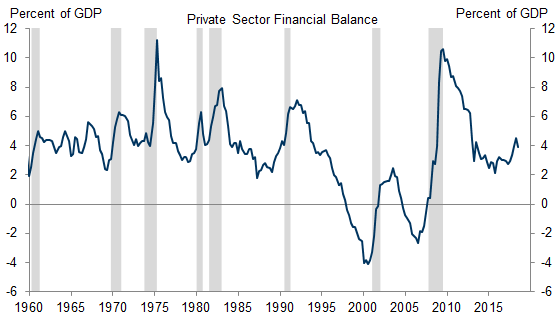

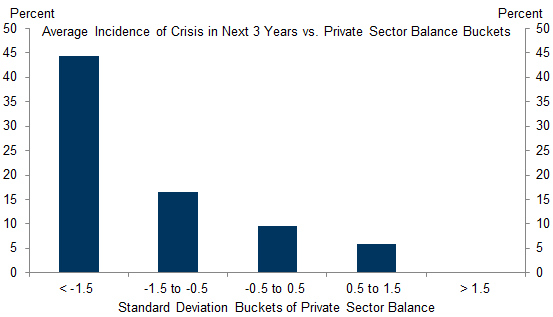

The fourth cause, financial risk, has been the main source of recent recessions. Old risks could reemerge, and the growing financialization of the economy or shocks from abroad could create new risks. But for now, regulation and private sector restraint in the post-crisis environment have kept financial risk subdued.

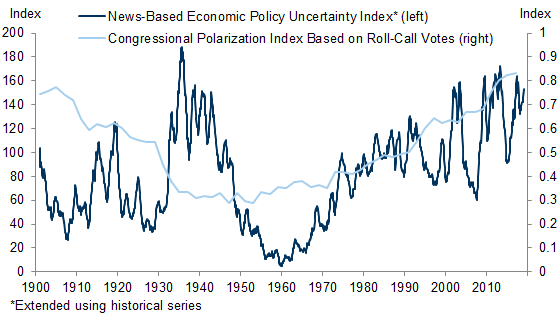

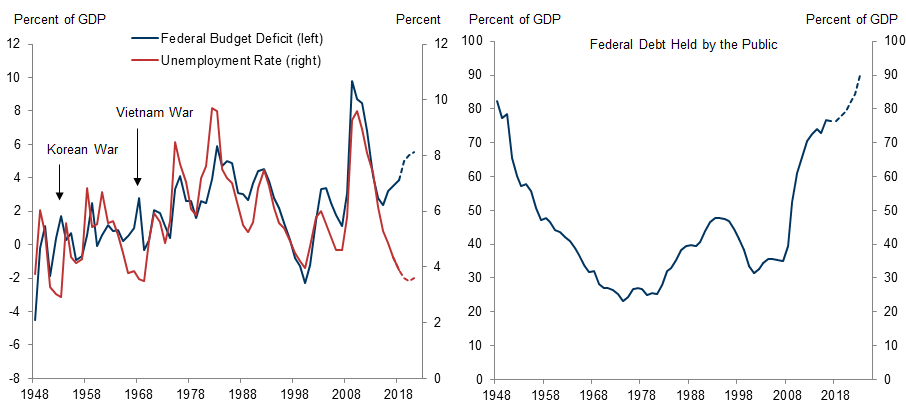

The fifth cause, fiscal policy, has historically meant major postwar demobilizations on a scale not seen since the Korean War. But here too, new risks could emerge in an era of political polarization, uncertainty, and dysfunction.

Overall, the changes underlying the Great Moderation appear intact, and we see the economy as structurally less recession-prone today. While new risks could emerge, none of the main sources of recent recessions—oil shocks, inflationary overheating, and financial imbalances—seem too concerning for now. As a result, the prospects for a soft landing look better than widely thought.

Learning from a Century of US Recessions

The Long View

The Great Moderation Revisited

Financial Restraint in the Post-Crisis Economy

New Fiscal Policy Risks in an Era of Political Dysfunction

Better Prospects for a Soft Landing

Jan Hatzius

David Mericle

- 1 ^ Charlie Himmelberg, “The Greater Moderation,” Global Markets Analyst, January 30, 2018.

- 2 ^ In particular, we use Willard Long Thorp, The Annals of the United States of America, 1926; Wesley C. Mitchell, Business Cycles as Revealed by Business Annals, 1926; Arthur Burns and Wesley Mitchell, Measuring Business Cycles, 1946; Victor Zarnowitz, Business Cycles: Theory, History, Indicators, and Forecasting, 1992; Marc Labonte and Gail Makinen, “The Current Economic Recession: How Long, How Deep, and How Different From the Past?”, 2002; and additional sources specific to individual recessions.

- 3 ^ James A. Kahn, Margaret M. McConnell, and Gabriel Perez-Quirós, “On the Causes of the Increased Stability of the US Economy,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, 2002; Steven J. Davis and James A. Kahn, “Interpreting the Great Moderation: Changes in the Volatility of Economic Activity at the Macro and Micro Levels,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2008.

- 4 ^ For a discussion of the role of monetary policy, see Ben Bernanke, “The Great Moderation,” February 20, 2004.

- 5 ^ The estimates in Exhibit 9 are from Daan Struyven and David Choi, “The Monetary Policy Response to Uncertainty,” US Economics Analyst, September 15, 2018.

- 6 ^ William C. Dudley and Edward F. McKelvey, “The Dark Side of the Brave New Business Cycle,” Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper, October 18, 1999; Hyman Minsky, “The Financial Instability Hypothesis,” The Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 74, May 1992.

- 7 ^ International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook,” April 2009.

- 8 ^ See “Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. “Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016.

- 9 ^ Alec Phillips, “How Nothing Gets Done in Washington,” US Economics Analyst, February 13, 2015.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.