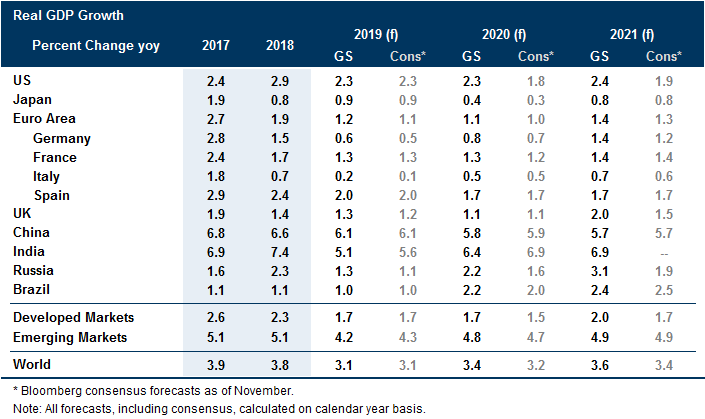

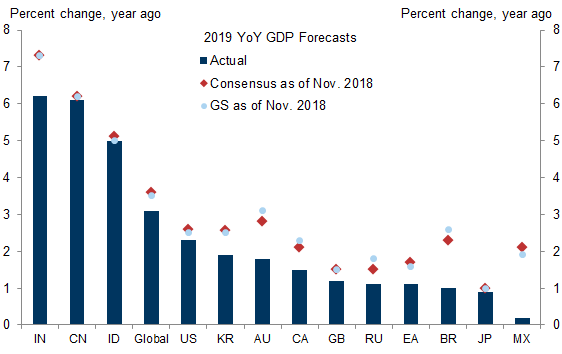

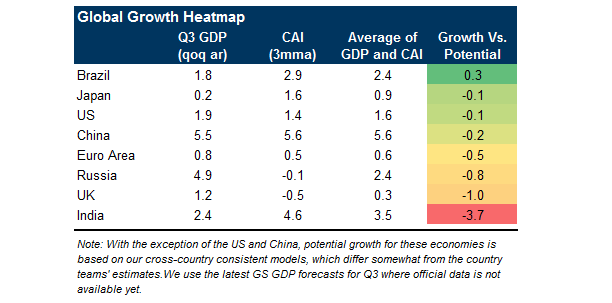

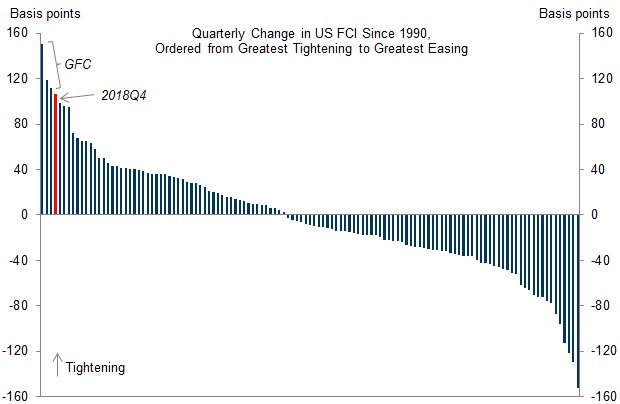

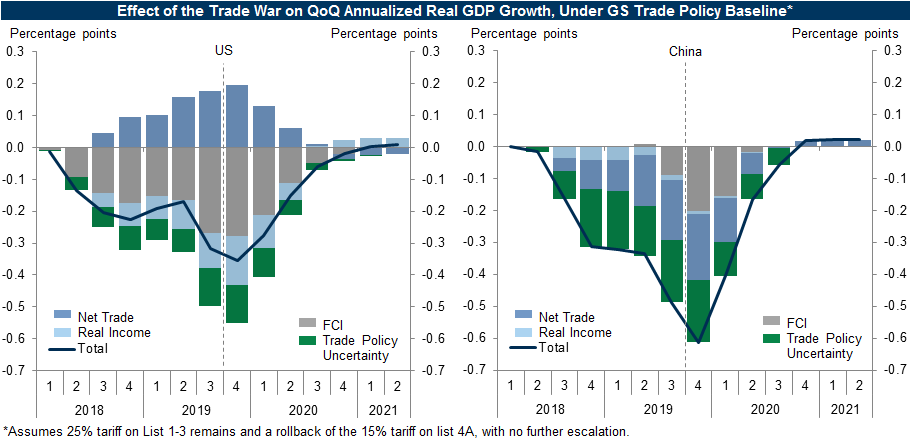

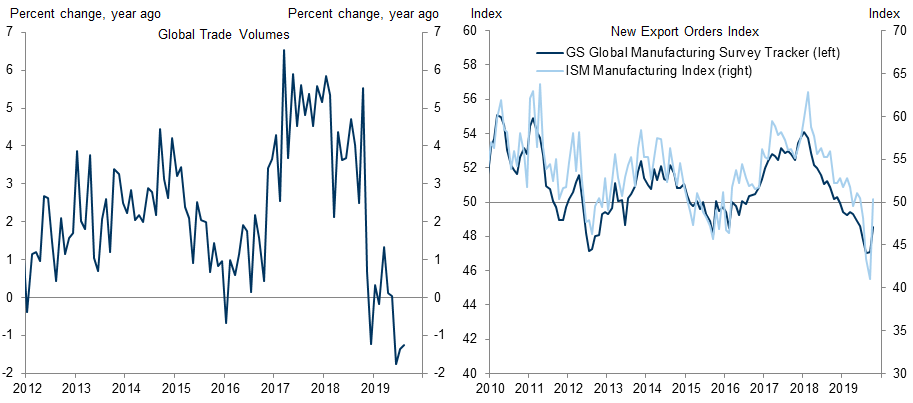

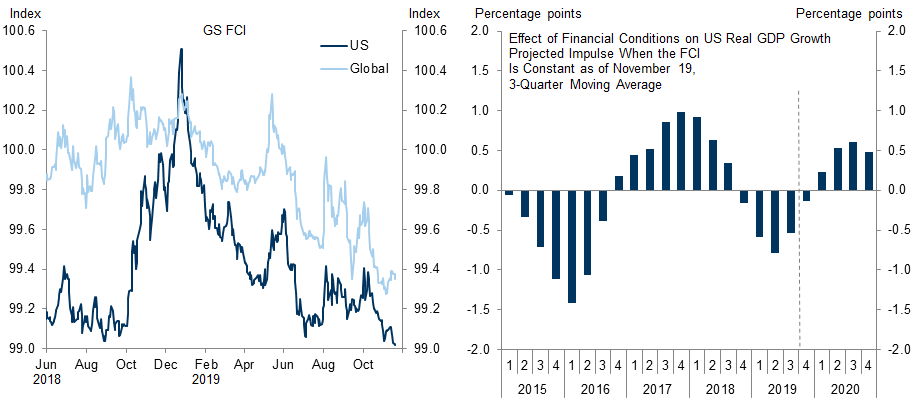

We expect the global growth slowdown that began in early 2018 to end soon, in response to easier financial conditions and an end to the trade escalation. Although annual-average GDP growth is likely to rise only modestly from 3.1% in 2019 to 3.4% in 2020, this conceals a more pronounced sequential pattern of slowing growth this year and—in our forecast—gradually rising growth next year.

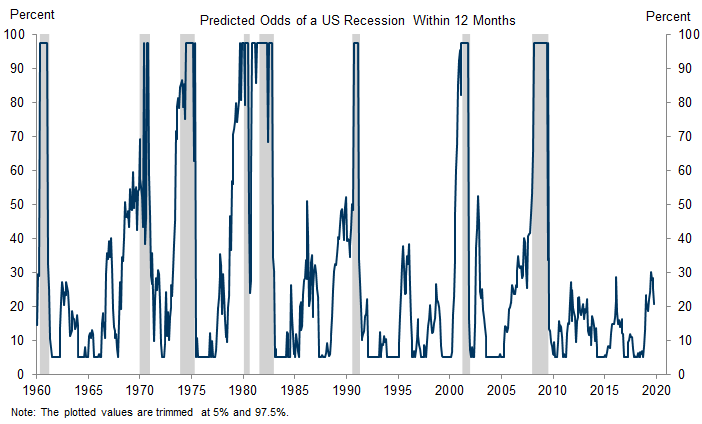

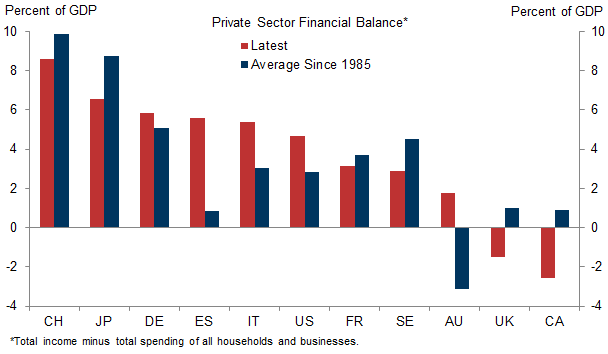

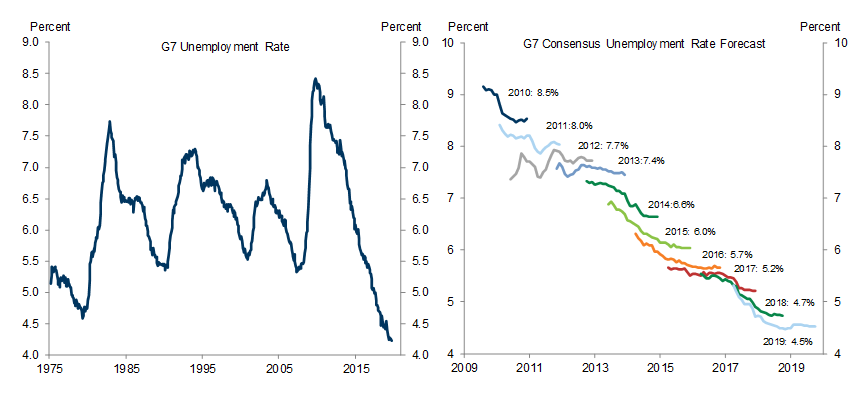

The risk of a global recession remains more limited than suggested by the flat yield curve, which partly reflects a structural decline in the term premium, and the low unemployment rate, whose predictive value for inflation and aggressive monetary tightening has fallen. We also take comfort from the absence of significant private sector financial deficits in all but a few advanced economies.

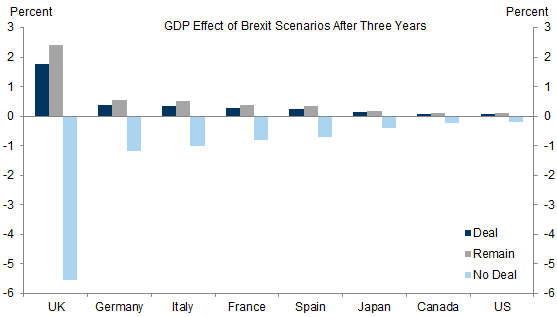

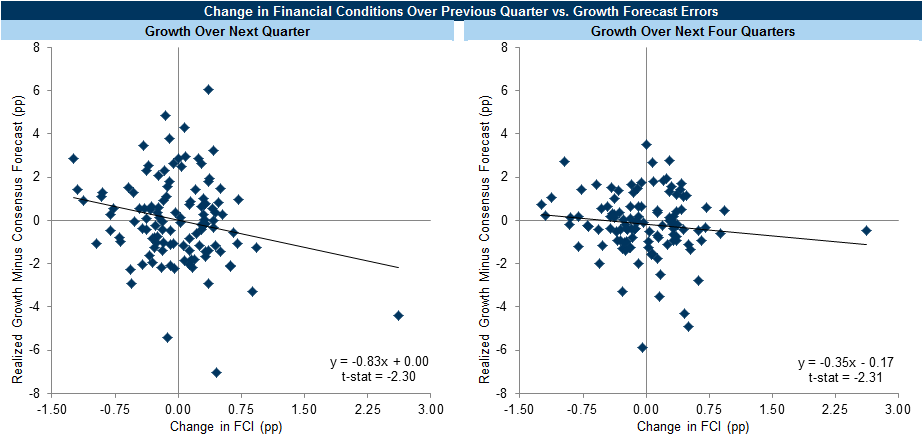

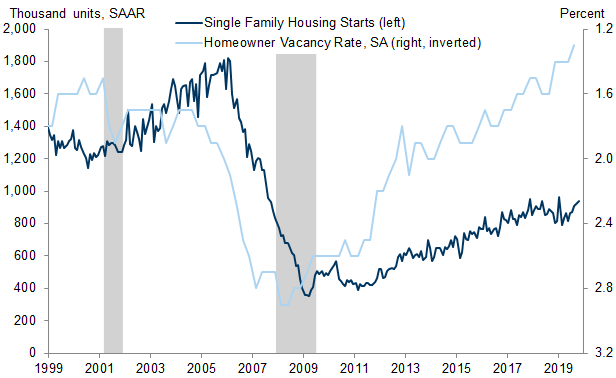

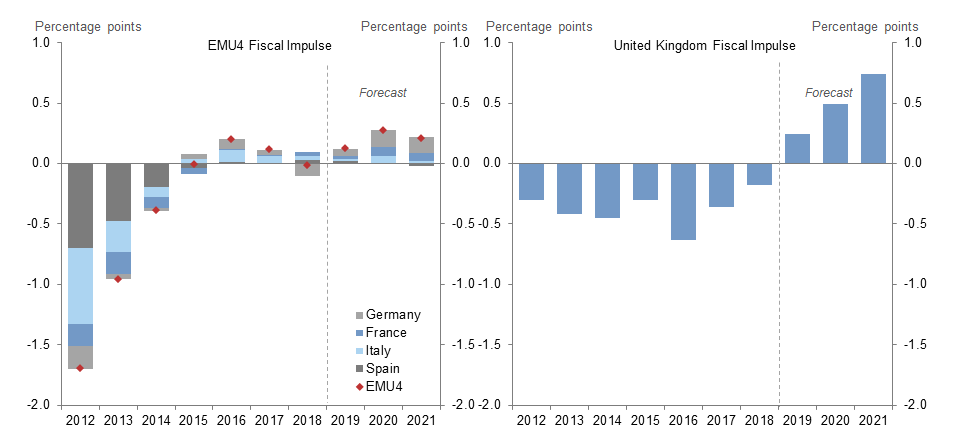

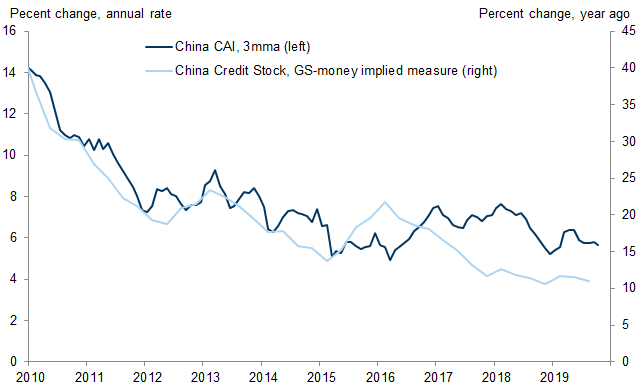

Our confidence that growth will improve sequentially is highest in the US, where demand is most responsive to financial conditions, and the UK, where we expect the Brexit drag to reverse and fiscal policy to ease. We look for a more gradual pickup in Europe, where the fiscal boost is likely to remain (too) limited, and Japan, where we are watching carefully for a negative impact from the October consumption tax hike. We expect growth in China to slow modestly from just above 6% to just below, in line with gradually decelerating potential.

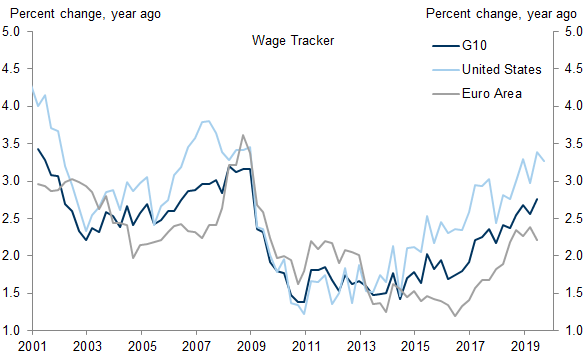

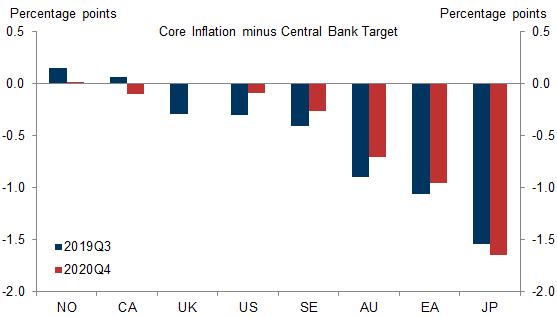

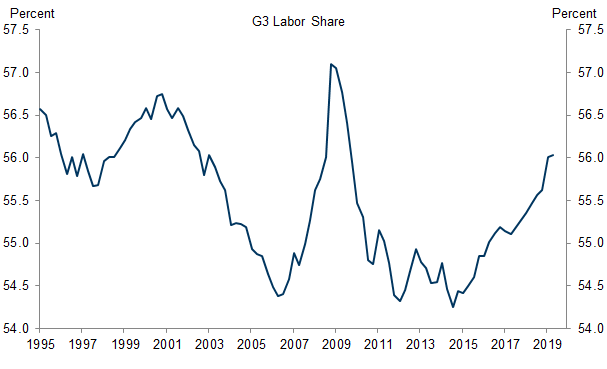

Across many advanced economies, we expect continued labor market improvement and upward pressure on wage growth, which is likely to push unit labor costs above central bank inflation targets. However, the pass-through to core price inflation should remain limited because the price Phillips curve is much flatter than the wage Phillips curve given stable inflation expectations.

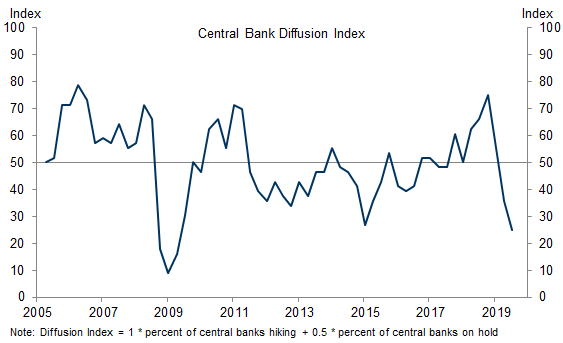

In our baseline forecast, most DM central banks stay on hold in 2020. At least in the early part of the year, however, the risk is on the side of further easing, especially in the Euro area and Japan where growth is weak and inflation far below target. We also expect further cuts in a number of EMs and smaller DMs.

Slightly better growth, limited recession risk, and friendly monetary policy should provide a decent background for financial markets in the early part of 2020. However, concerns about the impact of higher corporate taxes on profits could rise in the runup to the US presidential election. Even aside from politics, rising wage growth looks set to reduce profit margins over the next several years.

A Break in the Clouds

Recession Risk Still Limited

A Rising Tide …

… Should Lift Most Boats

Central Banks Move to the Sidelines

Profit Margins Under Pressure

- 1 ^ See Daan Struyven, David Choi, and Jan Hatzius, “Recession Risk: Still Moderate,” US Economics Analyst, October 27, 2019.

- 2 ^ See Jan Hatzius and Nicholas Fawcett, “The Private Sector Financial Balance: Mostly Clear Skies,” Global Economics Analyst, August 23, 2019. A breakdown of the aggregate US private sector financial balance shows healthy balances for both the household and business sectors and for business segments. See Spencer Hill, “Stuck in the Middle with You: Searching for Corporate-Sector Imbalances,” US Economics Analyst, November 12, 2018.

- 3 ^ See Alec Phillips, "Tariff Rollback and Its Risks," US Daily, November 11, 2019.

- 4 ^ See Daan Struyven, Hui Shan and Helen Hu, "The Trade War Drag on US-China Growth Should Abate in 2020," Global Economics Comment, November 18, 2019.

- 5 ^ See David Choi, “Do Forecasters Fully Account for Financial Conditions?” US Daily, November 12, 2019.

- 6 ^ See David Choi, “Consumption Leads the Way,” US Economics Analyst, November 2, 2019.

- 7 ^ See Adrian Paul, “UK—A Post-Election Pickup,” European Daily, November 13, 2019.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.