Climate change has increasingly drawn the attention of economists in both academic and policymaking circles. In this week’s Analyst we survey the literature on the economic effects of climate change and possible policy responses.

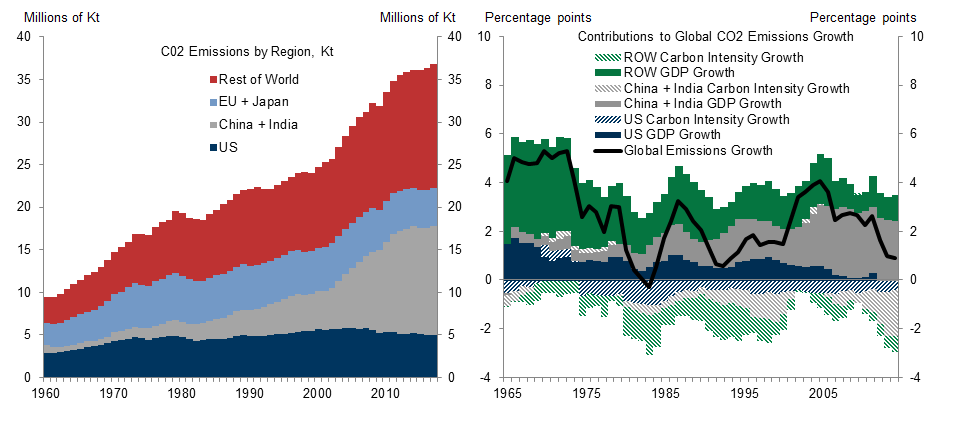

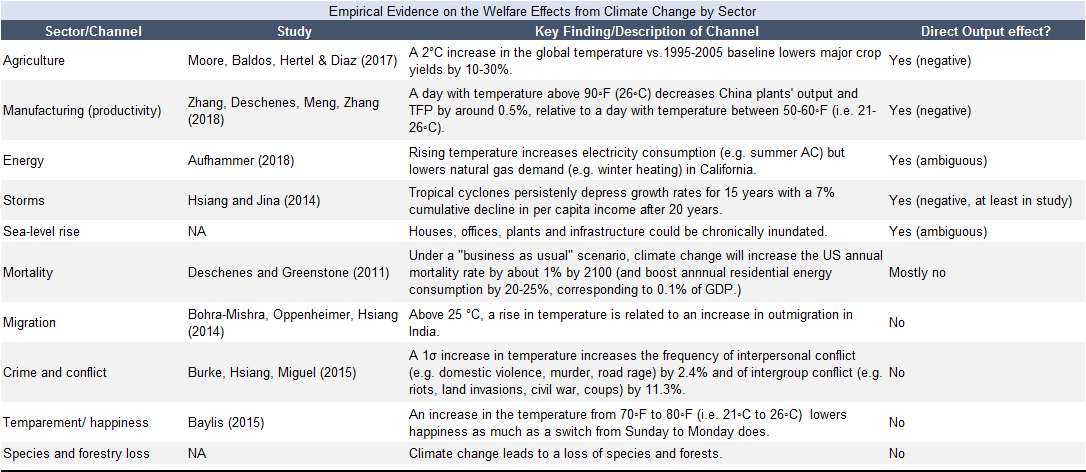

Researchers have estimated the welfare effects of climate change due to output loss and monetary damages as well as increased mortality, species loss, and environmental degradation. The empirical evidence suggests that climate change has likely already had a significant impact on economic welfare through a wide range of channels. The estimated welfare impact also tends to vary sharply across geographies and is often highly non-linear in temperature.

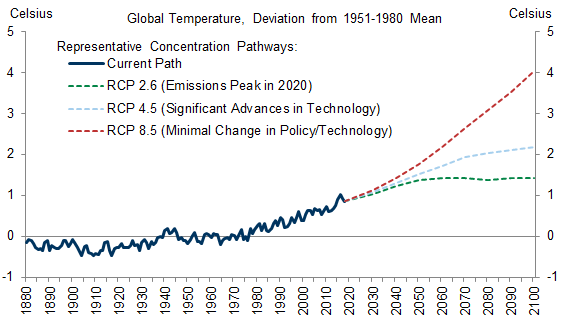

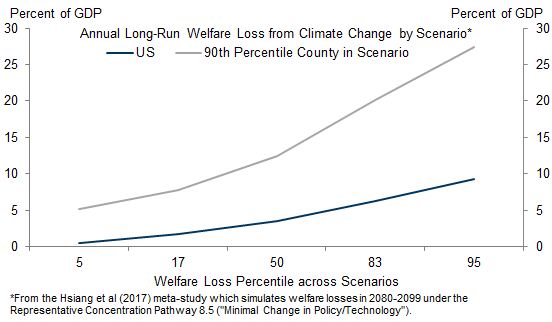

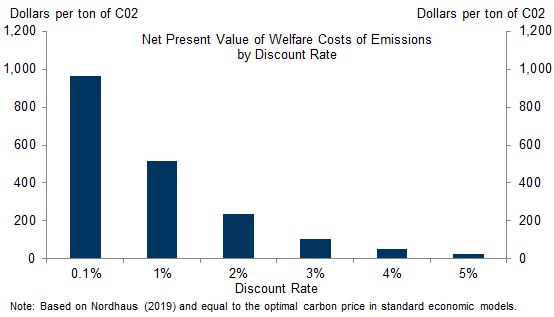

Most of the welfare costs of climate change are likely to come in the distant future. While there is considerable uncertainty over how much temperatures will rise, and how that will affect natural and human systems, growing evidence points to a significant risk of very large welfare losses.

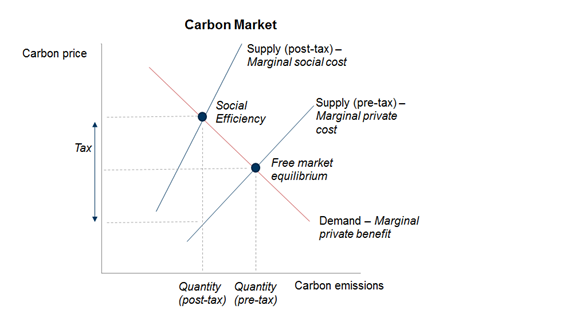

Economic principles suggest that market-based instruments like a carbon tax can efficiently deal with the negative externalities from carbon emissions. While simple in theory, most countries including the US have not implemented such policies. This likely reflects the global nature of the externality, which encourages free-riding, the highly uncertain welfare costs, and the challenges in choosing how much weight to place on future generations in cost-benefit analysis.

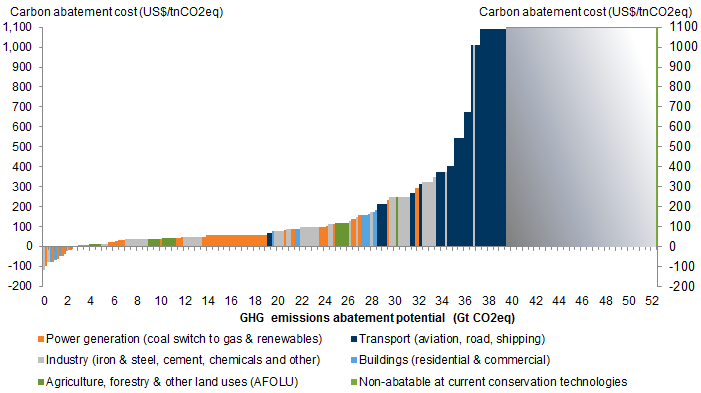

Analysis from our Energy equity analysts points to many available low-cost opportunities that would reduce emissions. The current cost curve steepens quickly, with rapidly rising costs at higher levels of decarbonization. Nevertheless, dynamic considerations, such as learning-by-doing, knowledge spillovers, and network effects, suggest that many investments that are costly today could still be efficient from a long-run perspective.

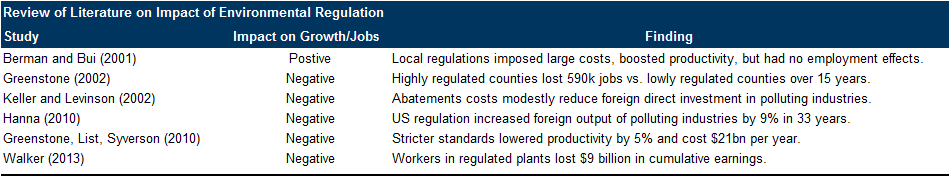

In the short run, the growth effects from decarbonization policies are likely ambiguous, with winners and losers across sectors, and are likely highly dependent on the policy details. Overall, our survey of the literature suggests that policies aimed at curbing emissions could trigger significant shifts and have the potential to raise welfare of current and especially future generations.

The Economics of Climate Change: A Primer

Surveying the Evidence on Welfare Effects from Climate Change

Projecting the Welfare Effects of Climate Change

Decarbonization Policy: Theory and Practice

The Growth Effects of Decarbonization Policies

David Choi

Daan Struyven

- 1 ^ This is particularly true when looking at carbon emissions per capita.

- 2 ^ Defined here as carbon emissions per unit of output.

- 3 ^ For instance, economists have relied on estimates on the value of a statistical life and estimates of the economic cost of crime.

- 4 ^ Andrew Boak, Bill Zu, and William Nixon, “The Macro Impact of the Bushfire Crisis,” Australia and New Zealand Economics Analyst, 6 January 2020.

- 5 ^ See Spencer Hill, “Hurricane Handbook: Natural Disasters and Economic Data,” US Economics Analyst, 9 September 2017 and Jan Hatzius, Sven Jari Stehn, and Shuyan Wu, “The Economic Effects of Hurricane Sandy,” US Economics Analyst, 2 November 2012.

- 6 ^ See Solomon Hsiang and Amir Jina, “The Causal Effect of Environmental Catastrophe on Long-Run Economic Growth: Evidence from 6,700 Cyclones,” NBER Working Paper, 2014. For example in the United States, employment in New Orleans has not recovered since Hurricane Katrina, and population projections suggest permanent output loss in Puerto Rico. The level of insurance coverage in an economy leads to very different paths of recovery from climate-related disasters, as shown in recent instances of hurricanes across different US states and Caribbean islands.

- 7 ^ Melissa Dell, Benjamin Jones and Benjamin Olken, “Temperature Shocks and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Last Half Century,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2012.

- 8 ^ Maximilian Auffhamer, “Quantifying Economic Damages from Climate Change,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2018.

- 9 ^ Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp, Amir Jina et al.,"Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States," Science, 2017.

- 10 ^ See William Nordhaus, “Climate Change: The Ultimate Challenge for Economics,” American Economic Review, 2019.

- 11 ^ See for example Julius Andersson, “Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming, and Jean-Thomas Bernard and Maral Kichian, “The Long and Short Run Effects of British Columbia’s Carbon Tax on Diesel Demand,” Energy Policy, 2019.

- 12 ^ One proposal to enforce global cooperation suggested by William Nordhaus is a “climate club,” in which members agree to put a price on carbon and to tax imported goods from non-member countries. The lack of a “carbon border tax” has also made existing proposals unpopular with unions, as energy intensive industries move abroad, leading to carbon leakage.

- 13 ^ Even if future generations are weighted equally to current generations, an argument for using market discount rates is that future generations would potentially benefit more from other investments that increase the capital stock and increase consumption in the future. See Gary Becker, Kevin Murphy, and Robert Topel, “On the Economics of Climate Policy”.

- 14 ^ Michele Della Vigna et al., “Carbonomics: The Future of Energy in the Age of Climate Change, “ 11 December 2019.

- 15 ^ Kenneth Gillingham and James Stock, “The Cost of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2018.

- 16 ^ These dynamic considerations are one reason why some seemingly cost-effective ways of reducing emissions, such as moving from coal to gas, may not be efficient in the long run if there is path dependence.

- 17 ^ Daron Acemoglu, Ufuk Akcigit, Douglas Hanley and William Kerr, “Transition to Clean Technology”, Journal of Political Economy, 2016.

- 18 ^ Philippe Aghion et al, "Carbon Taxes, Path Dependency and Directed Technical Change: Evidence from the Auto Industry," Journal of Political Economy, 2016.

- 19 ^ The net short-term growth effect from reallocating workers and capital from a polluting to a green sector may be somewhat negative if the former is more productive from a narrow GDP perspective.

- 20 ^ Adrian Paul and Silvia Ardagna, “Going Green” European Economics Analyst, 7 June 2019.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.