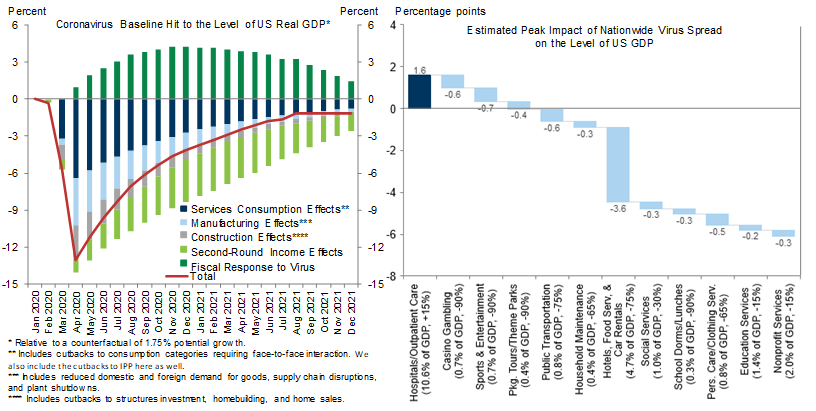

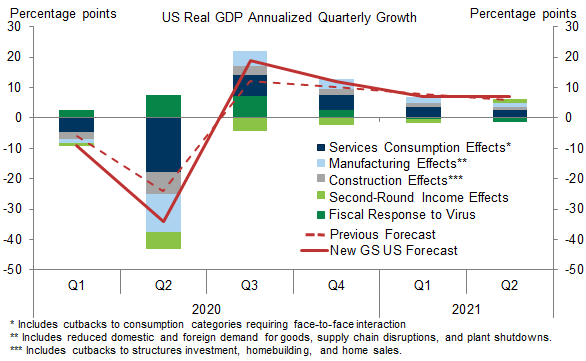

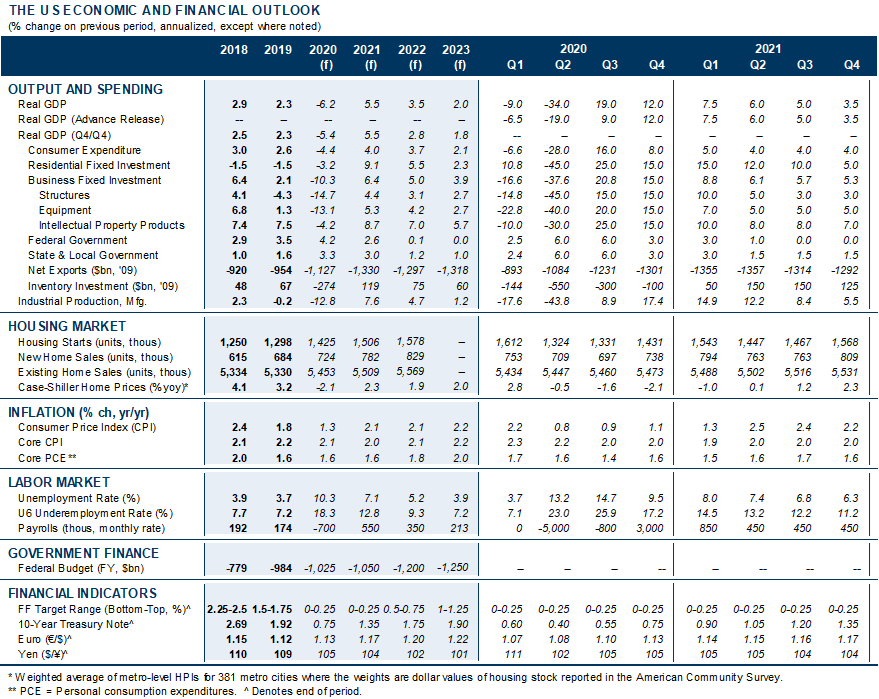

We are making further significant adjustments to our GDP and employment estimates. We now forecast real GDP growth of -9% in Q1 and -34% in Q2 in qoq annualized terms (vs. -6% and -24% previously) and see the unemployment rate rising to 15% by midyear (vs. 9% previously). However, we have upgraded our expectations for the recovery after midyear, with a 19% qoq annualized GDP gain in Q3 (vs. 12% previously). Our estimates imply that a bit more than half of the near-term output decline is made up by yearend and that real GDP falls 6.2% in 2020 on an annual-average basis (vs. 3.7% in our previous forecast).

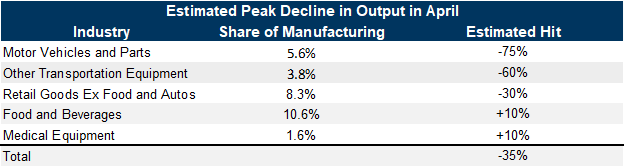

These forecast changes reflect the net effect of two directionally offsetting changes. On the one hand, the anecdotal evidence and the sky-high jobless claims numbers show an even bigger output and (especially) labor market collapse than we had anticipated. This not only means deeper negatives in the very near term but also raises the specter of more adverse second-round effects on income and spending a bit further down the road.

On the other hand, both monetary and fiscal policy are easing dramatically further, which will tend to contain these second-round effects and add to growth down the road. The Phase 3 fiscal package was much bigger than we had expected, we now anticipate a Phase 4 package focused on state fiscal aid, and the Fed is likely to use the $454bn addition to the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund aggressively to sustain the flow of credit to private-sector and municipal borrowers.

We have not made major changes in our assumptions on the time path of the recovery. While the uncertainty is substantial, we expect the lockdowns and social distancing to result in sharply lower new infections over the next month, and our baseline is that slower virus spread and adaptation by businesses and individuals should set the stage for a gradual recovery in output starting in May/June.

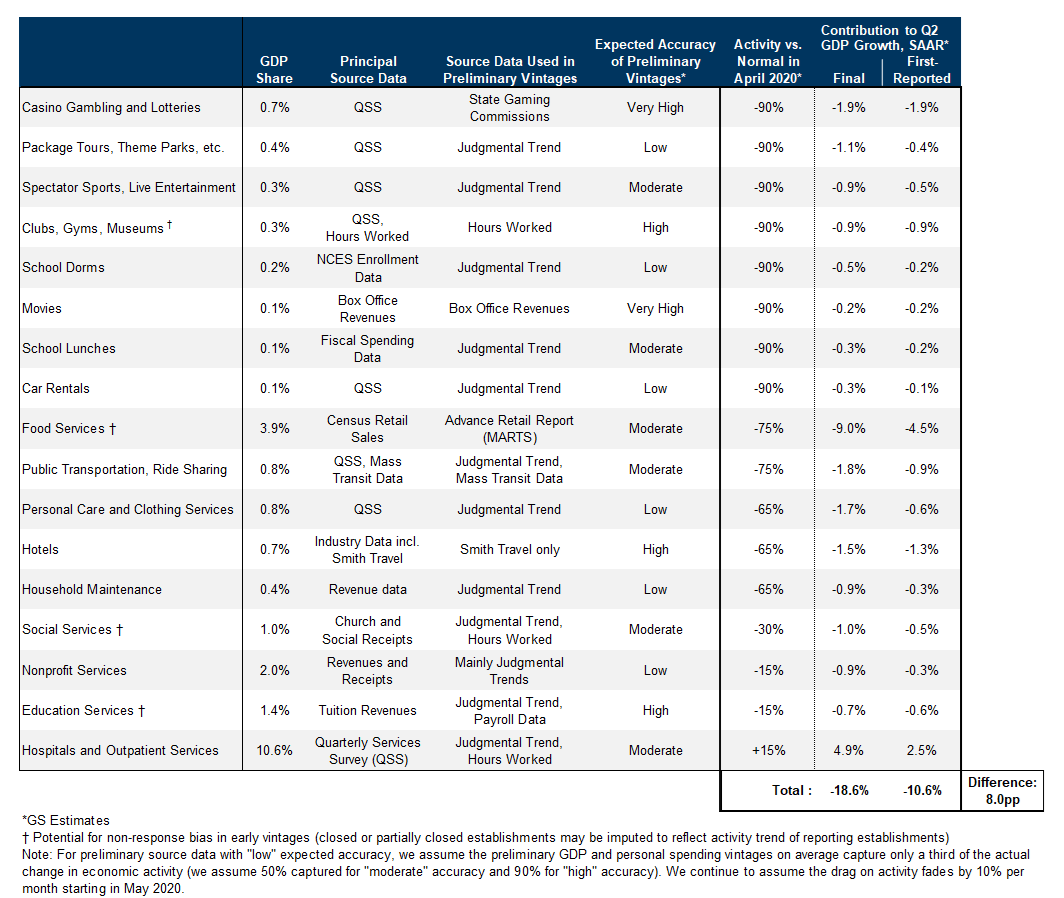

The depth of the near-term output decline is unlikely to show up fully in the Q1/Q2 advance GDP reports, many of whose components are estimated on the basis of judgmental trends that are only replaced by actual source data in later vintages. If the true Q2 decline is 34%, we would expect a reported decline of “only” -19% in the advance report.

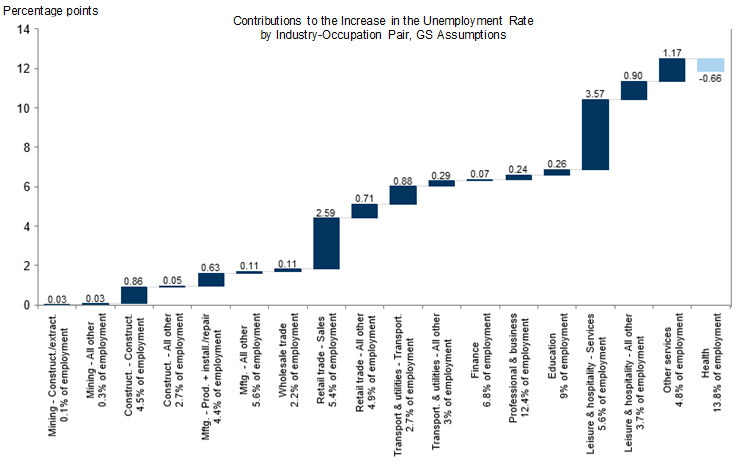

By contrast, the labor market data—especially jobless claims and the household survey—are likely to provide much better real-time signals. Our working assumption during this crisis is that each 1pp increase in the unemployment rate corresponds to roughly a 1% decline in the level of real GDP relative to trend. We plan to lean heavily on this relationship—and its industry-level counterparts—to keep our GDP estimates up to date in coming months.

The Sudden Stop: A Deeper Trough, A Bigger Rebound

A Deeper Trough in GDP…

…And a Dramatic Hit to Employment

Focus on the Labor Market

US Economics Team

- 1 ^ We expect a few methodological pivots as statisticians seek alternative data on which to base their estimates—but not enough to avoid sizeable measurement error in several GDP components, as the BEA may be reluctant to assume outsized declines in spending and investment activity in cases where alternative data is lacking or has insufficient history.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.