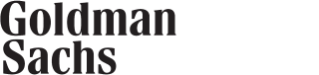

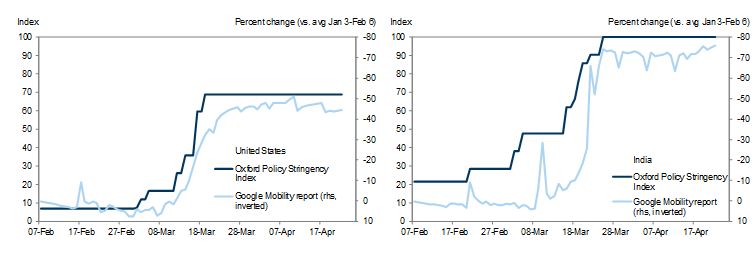

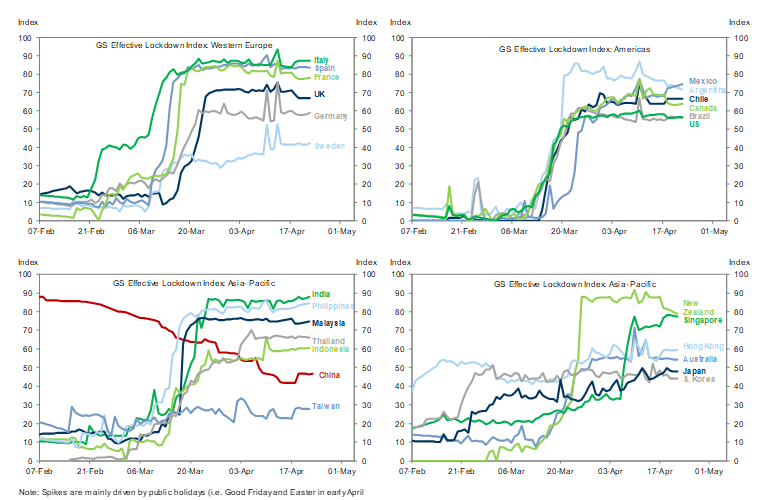

In today’s note, we combine two prominent measures of lockdowns and social distancing—the Oxford policy stringency index and the Google global mobility reports—into an Effective Lockdown Index (ELI) for every economy under our coverage. Globally, the ELI rose sharply in late March and has been stable since then. Readings are high almost everywhere, with only mainland China on a clear downward trend.

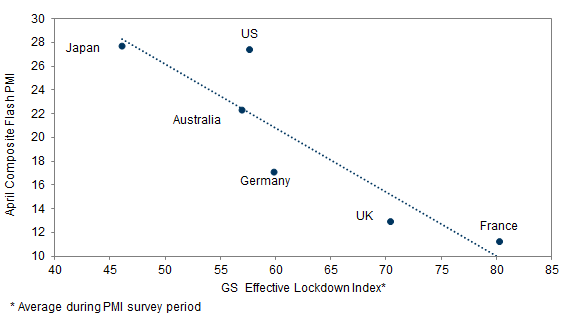

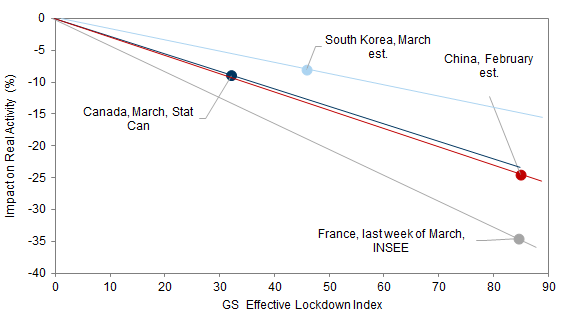

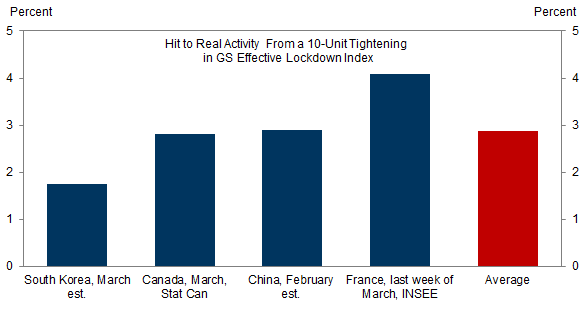

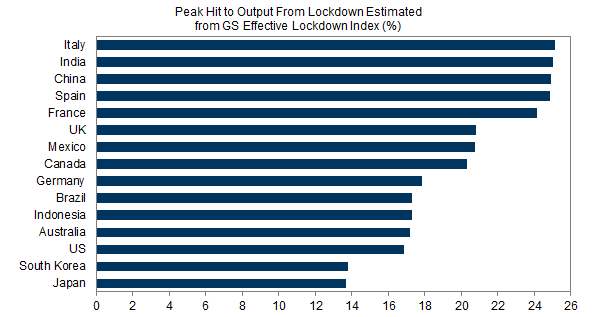

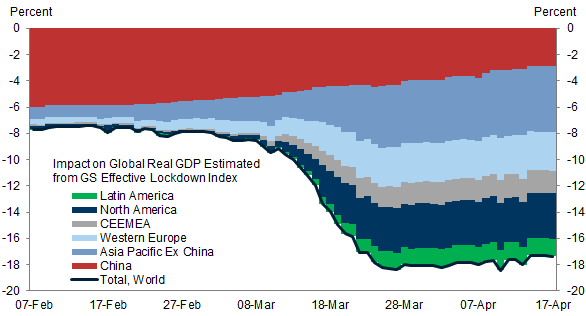

On a cross-country basis, the ELI correlates closely with measures of economic activity such as the flash PMIs for April. Building on that link, we use preliminary estimates from statistical agencies in four countries—Canada, China, France and South Korea—to construct an ELI-implied hit to the level of GDP for every economy under our coverage. This hit currently stands at 17% globally; relative to pre-virus trend growth of about 3%, this implies year-on-year GDP growth of -14% as of late April. The impact on growth for Q2 as a whole is likely to be smaller, assuming activity recovers somewhat in coming months.

A number of important caveats are in order. First, while combining two different indicators should reduce measurement error, the ELI is likely to be a noisy measure of lockdowns and social distancing. Second, our translation of the ELI into GDP assumes a linear relationship and is based on preliminary estimates from just four countries. Third, we ignore cross-country differences in the GDP weights of activities with large amounts of face-to-face interaction. Fourth, the relationship between the ELI and GDP may change over time as households and firms adapt their behavior and policymakers optimize for the least economically damaging restrictions.

The GS ELIs can be downloaded here.

Measuring the Impact of Lockdowns and Social Distancing on Global GDP

Measuring Lockdowns and Social Distancing

The Impact of Lockdowns and Social Distancing on Activity

Caution

Daan Struyven

Andrew Tilton

Jan Hatzius

- 1 ^ See Andrew Tilton, “Lockdown lexicon—virus control strategies and their economic implications”, Asia Economics Analyst, April 15, 2020.

- 2 ^ For more details, see Hale, Thomas, Sam Webster, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, and Beatriz Kira (2020). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.

- 3 ^ International restrictions should not affect domestic behavior much while contact tracing is a labor-intensive effort that involves health officials contacting a large number of potentially affected individuals.

- 4 ^ The projections are based on regressions of the daily change in the Google measure on the (7-day moving average) daily change in the Apple measure and weekend effects. For a few countries, we also use projections from regressing the Google level on the Apple level.

- 5 ^ For a detailed analysis of lockdown policies at the US state- and country level, see Blake Taylor, “Measuring Lockdown: State Orders, Economic Activity, and Social Distancing Across the US”, US Economics Analyst, April 12, 2020.

- 6 ^ The decline in China’s ELI is a result both of easing in the Oxford policy variables and of an increase in our mobility proxy.

- 7 ^ Stat Can notes the hardest hits in travel, tourism, personal transportation, restaurants, accommodation, personal services, non-food retailing, entertainment and sporting events, and movies exhibition.

- 8 ^ While the construction and manufacturing sectors have recovered slightly, the hits remain very large in manufacturing of transportation goods and electric equipment, construction, hotels and restaurants, transportation- and retail services.

- 9 ^ If the ELI were at 100 and if there was literally no movement to public transportation, workplaces or retail areas, jobs involving any physical actions would likely not happen and GDP would likely decline by more than 28%. The BLS and academic studies estimate that 30-35% of the US jobs can be done from home.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.