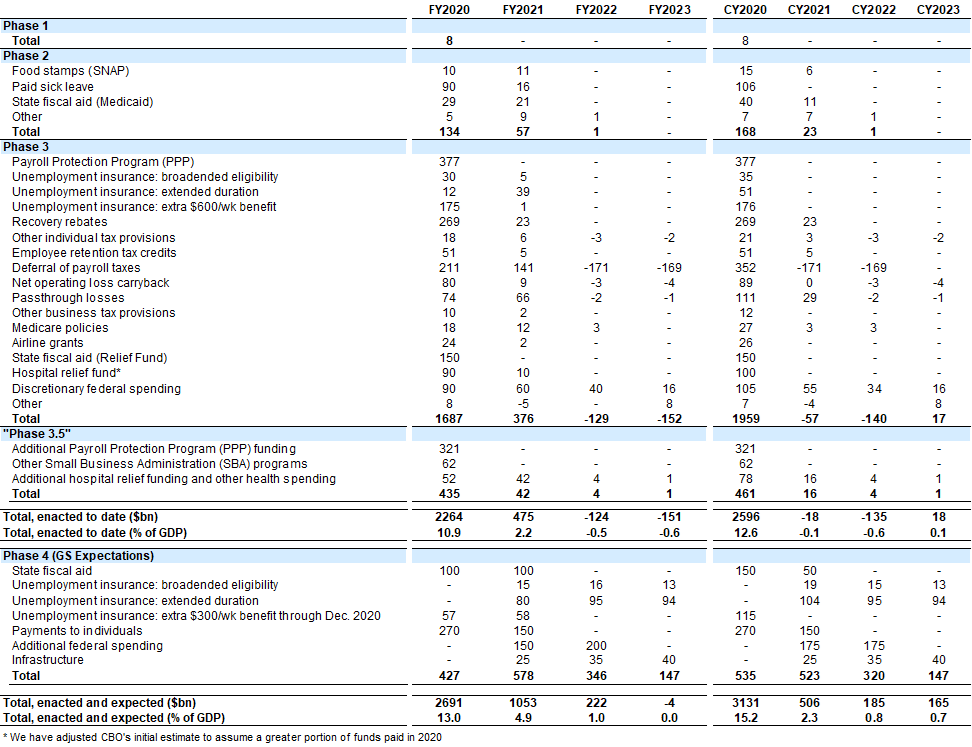

As Congress returns to Washington—the Senate returns May 4th, the House plans to return a week later, on May 11th—attention has already turned to another package of policies to address the economic effects of COVID-19.

However, after four rounds of legislation over the last two months, there appears to be less agreement on what a fifth round of policy measures should include and, to a lesser extent, whether further fiscal intervention will even be necessary. Despite this, we expect that Congress will enact additional measures by mid-year.

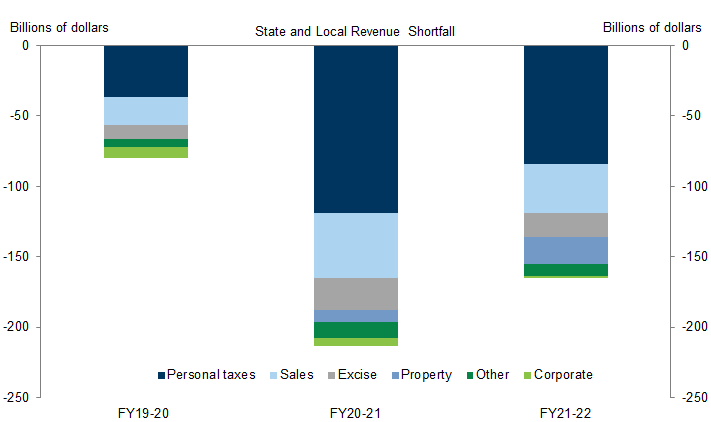

Fiscal aid to state and local governments appears to top the list of priorities. We estimate that states will run a cumulative shortfall over the next two years of roughly $450bn (around 1% of GDP over that period). Measures that Congress has passed to date and rainy day funds are likely to cover less than half that amount, and we expect Congress to provide another $200bn to shore up state and local budgets.

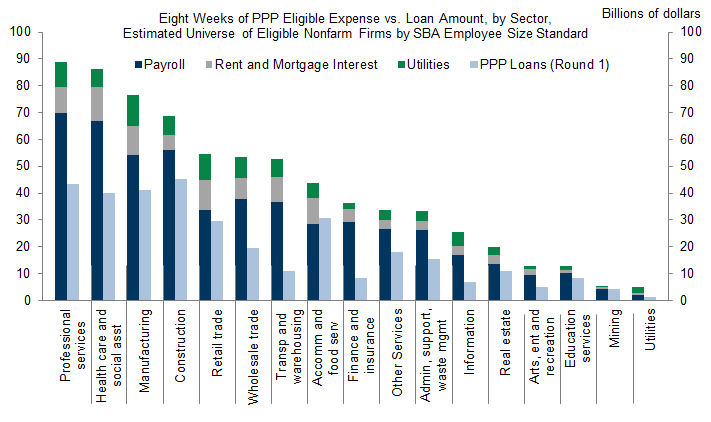

Congress recently renewed funding for the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for small businesses, but we do not expect further funding. There are other options to assist small businesses without increasing PPP funding, however, including extending the period to incur forgivable expenses under PPP beyond 8 weeks. In addition, businesses will soon be able to obtain loans via the Fed’s Main Street Lending Program (MSLP), and there is potential for a broader wage subsidy program.

We expect Congress will extend both the extra $600/week benefit payment expiring July 31 as well as the expanded duration and eligibility requirements, which are scheduled to expire at year-end. Additionally, while another round of payments to individuals has fallen out of the headlines, we continue to expect that Congress will approve some type of additional tax benefit for individuals this year. President Trump has once again suggested a payroll tax cut, while many members of Congress appear open to additional rebate checks.

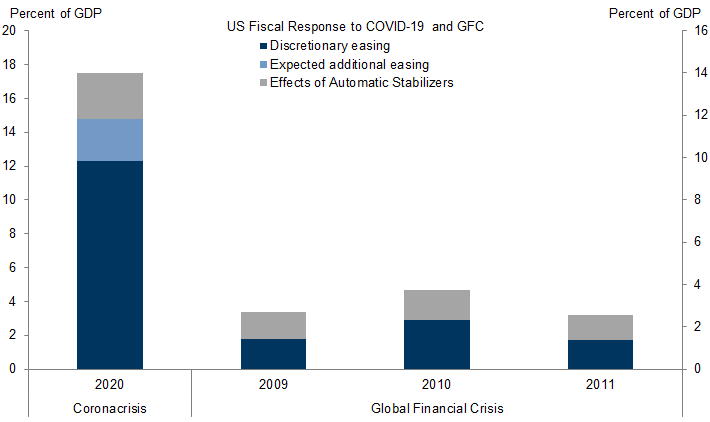

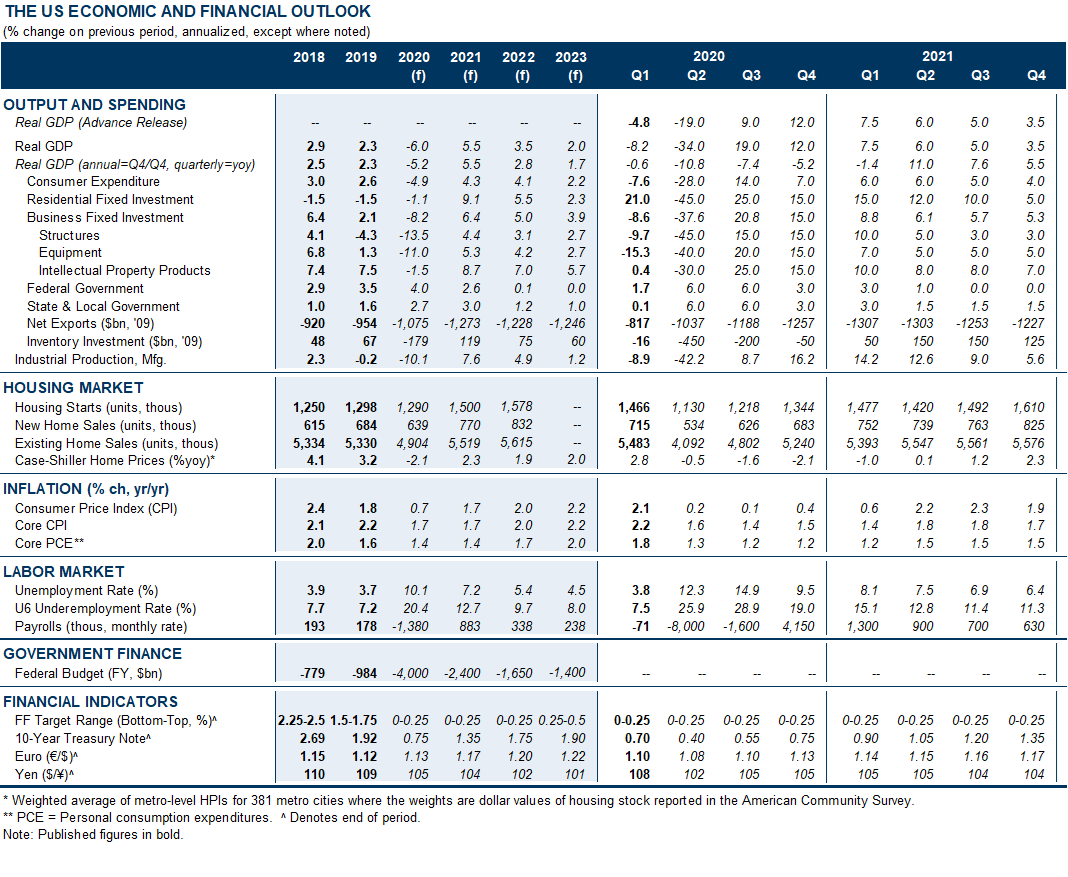

Overall, we expect Congress to approve fiscal measures adding another $550bn (2.6% of GDP) in 2020, taking total discretionary fiscal policy measures to $3.1 trillion (15.2% of GDP) this year.

Fiscal Policy: The Next Round

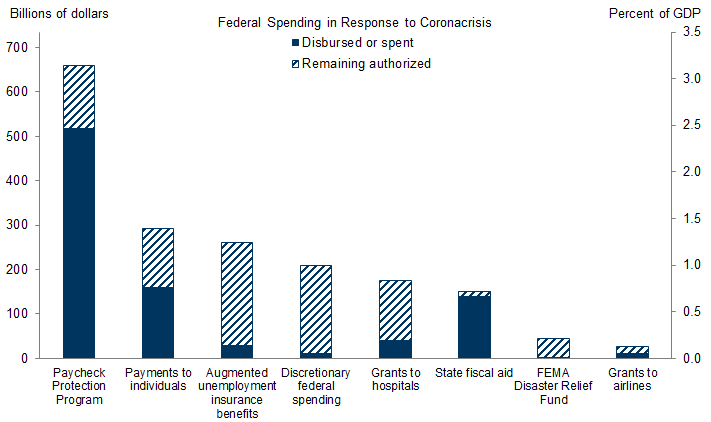

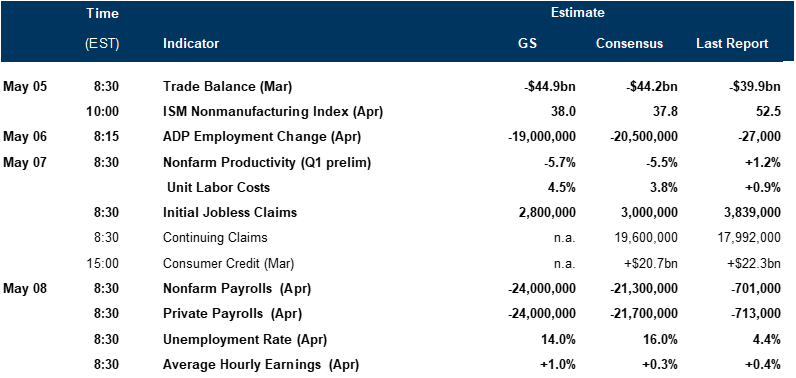

Payments to individuals: $160bn out of $292bn. Treasury began to deposit economic impact payments (stimulus checks) in taxpayer accounts starting in mid-April. Treasury reported that as of April 17 it had made 90 million payments amounting to $160bn, and daily tax refund data suggests that stimulus payments have slowed since that date. Another $110bn in payments will likely occur over the next several weeks, and about $20bn will be paid out in early 2021 as a tax refund.

Federal unemployment insurance expansion: approximately $30bn out of $262bn. The CARES Act adds an additional $600 benefit to weekly unemployment insurance payments, broadens eligibility, and extends the benefit period. Due to processing delays, benefits paid have lagged continuing jobless claims. Individuals received $48bn in unemployment insurance benefits in April, roughly $30bn of which we estimate is new federal benefits and $18bn is standard benefits.

Paycheck Protection Program: $518bn out of $698bn. Congress appropriated an additional $321bn for the PPP after the first round of funding ran dry, of which roughly $175bn has been disbursed over the last week.

State fiscal aid: $140bn out of $150bn. The CARES Act created a $150bn fund to compensate states for public COVID-related expenses. Nearly all of the funds have been paid to states, but this will not necessarily translate into immediate state spending.

Hospitals: $40bn out of $150bn. The CARES Act provided $100bn in relief for hospitals, and the “Phase 3.5” legislation added $75bn more. It appears that $40bn has already made its way to hospitals. Much of the remainder has been earmarked for costs related to the uninsured, and might be paid more slowly. Nevertheless, payments just in April already exceeded the amount CBO expected to be paid in FY2020.

Airline grants: $12bn out of $26bn. Several airlines have taken advantage of direct grants to cover payroll conditional upon avoiding layoffs or furloughs and accepting restrictions on stock buybacks and dividends.

FEMA disaster relief fund: $3bn out of $45bn. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has an additional $45bn in spending authority in response to COVID-19. However, emergency spending has been modest in response to the crisis so far at around $3bn.

Discretionary federal spending: Less than $10bn out of $210bn. The CARES Act included a number of smaller spending provisions, many of which look likely to take a bit longer before they increase federal outlays.

What’s Still on the Agenda

Alec Phillips

Blake Taylor

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.