As the upcoming school year approaches, it is still unclear if schools will be able to reopen. While reopening carries virus risks, the costs to the economy and students of keeping schools closed are also substantial.

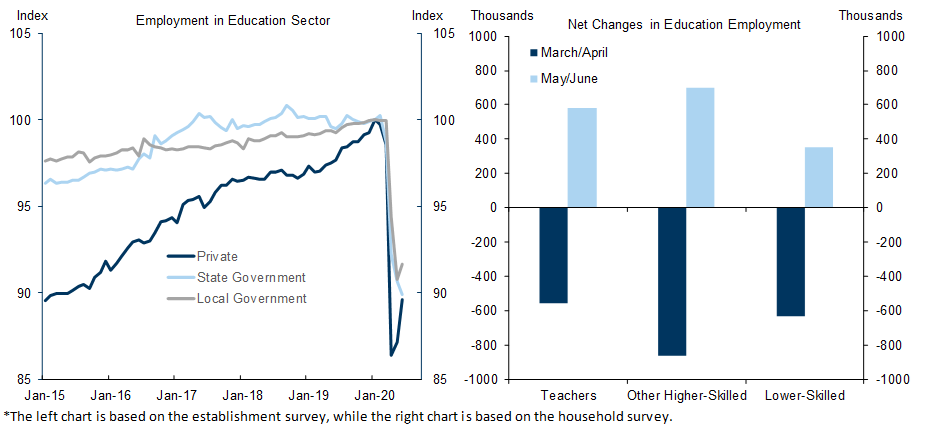

School closures directly reduce employment in the education sector, which fell dramatically following widespread school closures in March. We estimate that shutdowns in the education sector directly subtracted 2.2pp from annualized growth in Q2. School closures may also have a large impact on other parts of the economy closely tied to the education sector, such as food providers for meal programs and businesses in college towns.

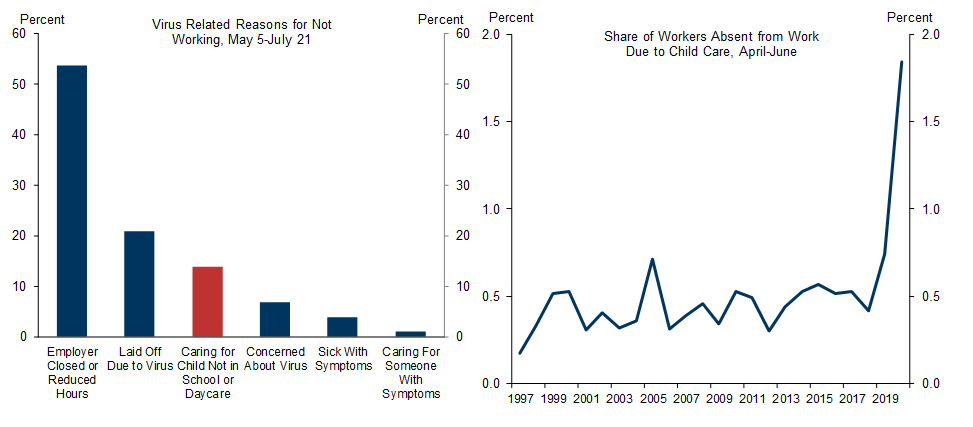

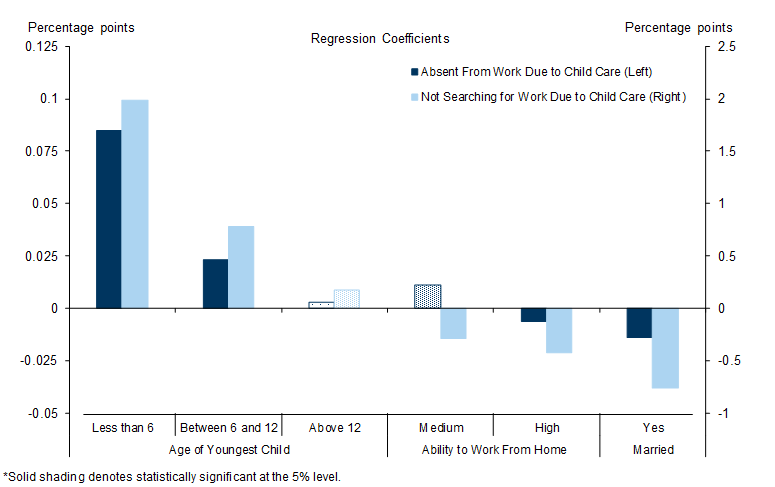

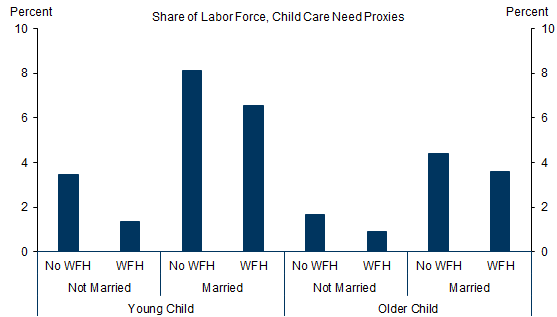

School closures also indirectly weigh on employment and productivity by increasing child care needs, which we find caused a large increase in worker absences. Single parents, workers that cannot work from home, and parents with young children are more at risk of not working due to child care needs. We estimate that roughly 24mn workers, or 15% of the labor force, are in at least two of these three situations.

School closures may also have many other important long-run costs, such as lower-quality education, a lack of social and emotional skill development, mental health problems, food insecurity, and worsening income and educational inequality.

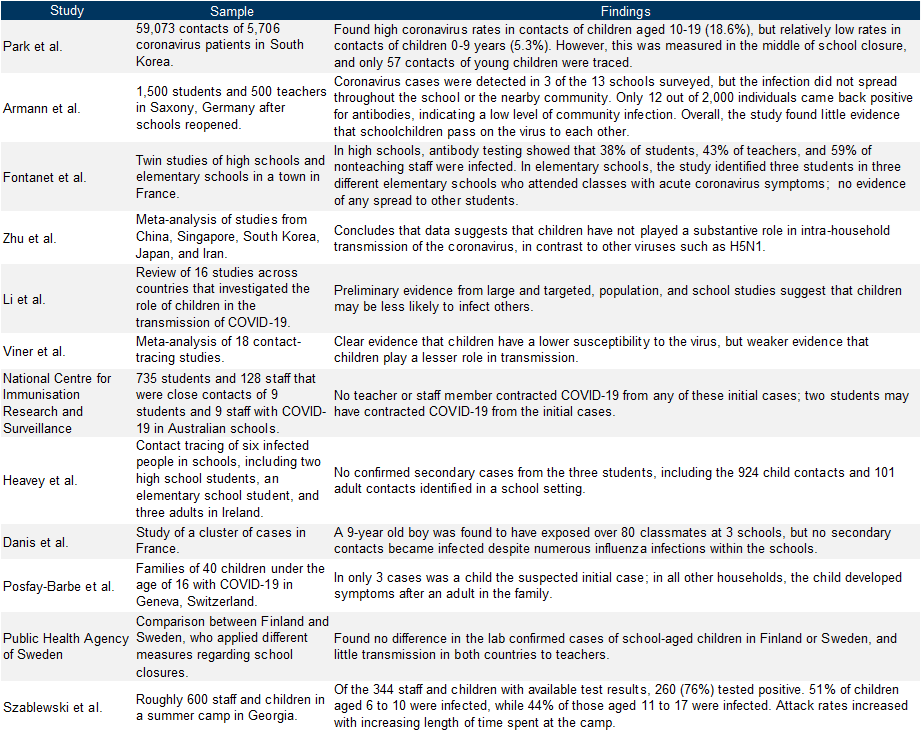

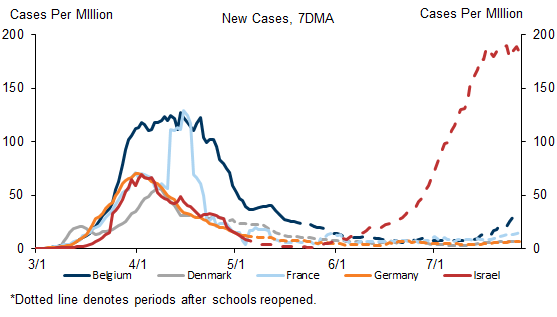

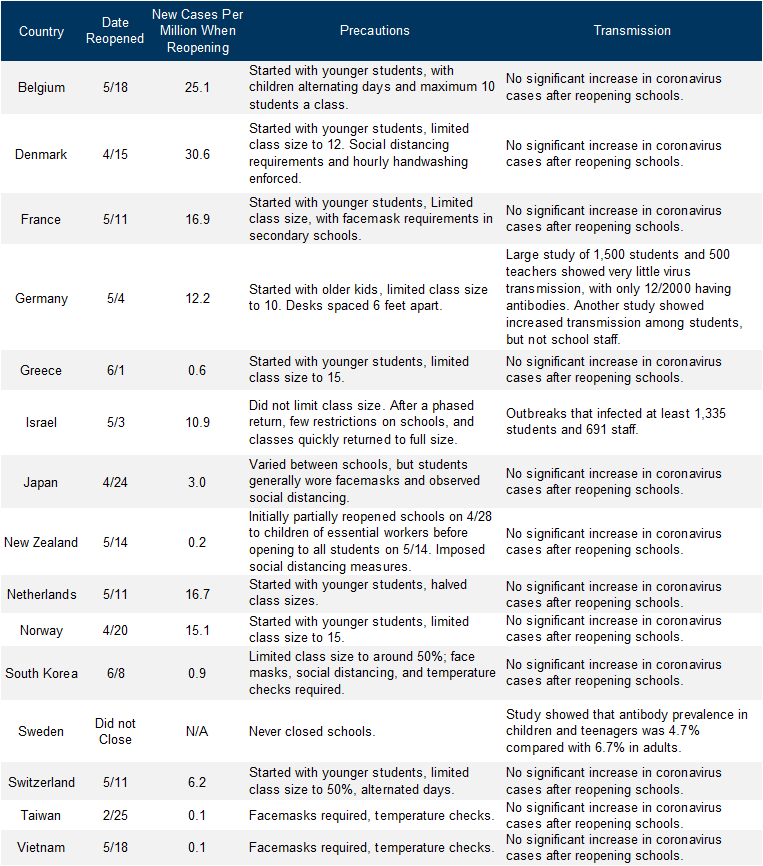

Preliminary evidence suggests that younger children may be less likely to transmit the virus to others, and international experience also shows that it may be possible to reopen schools without triggering a spike in virus cases. However, countries with successful school reopenings had significantly less virus spread than the US currently has, suggesting much higher risks in reopening for most of the US.

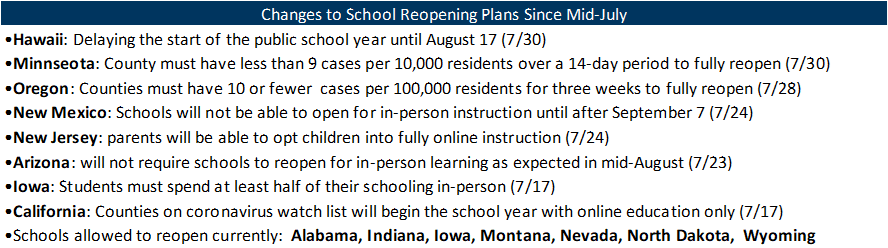

A growing number of states and districts have already pushed back start dates for in-person instruction. The reopening of schools will likely be a staggered process in the US, and depend crucially on whether the virus spread among the broader population is first managed.

The Reopening of Schools

The Economic Costs of School Closures

Schools and Virus Transmission

The Outlook for Reopening Schools

David Choi

Joseph Briggs

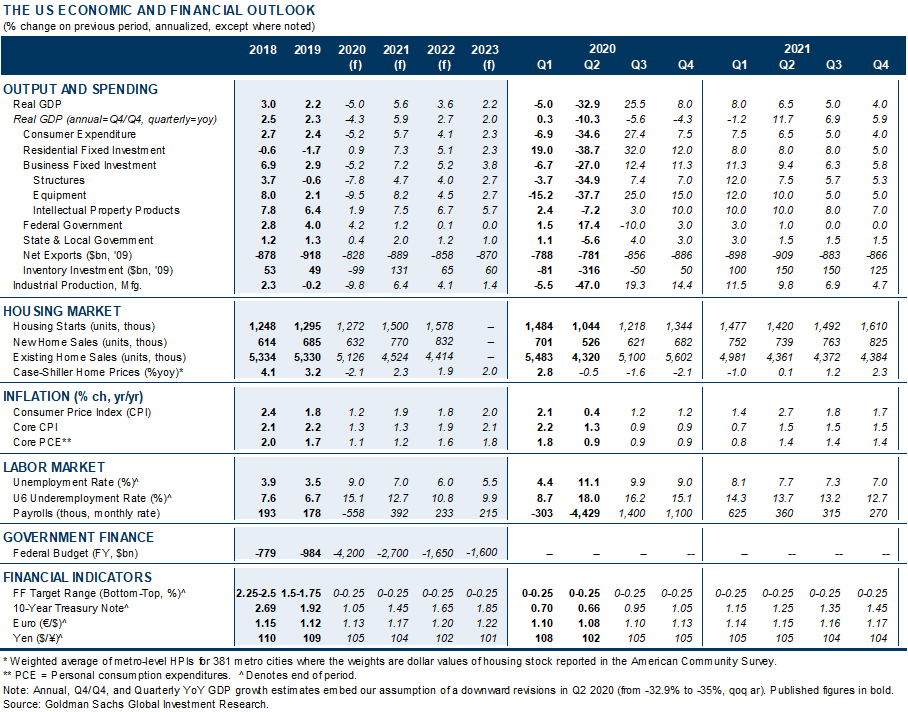

The US Economic and Financial Outlook

Forecast Changes

- 1 ^ Schooling enters GDP both through personal consumption expenditures of education services, as well as state and local government expenditures on public education. We assume a slightly smaller decline for public education, proportional to the relative declines between private employment and state and local government employment in the education sector.

- 2 ^ See for example Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why is the United States Falling Behind?” American Economic Review, 2013.

- 3 ^ For instance, in one striking anecdote, a CDC study found that school closures in Kentucky in 2008 due to an influenza outbreak led to an adult having to miss work to provide child care in 29.1% of households in which the child’s school had to close.

- 4 ^ Slightly more than 6 million workers according to the Census Pulse Survey.

- 5 ^ Some households may have informal care arrangements, such as extended family who they do not live with; however, this may be less possible currently due to social distancing guidelines, especially for older people such as grandparents.

- 6 ^ Meyers and Thomasson find that the 1916 polio pandemic, which led to quarantines and closed schools, led to less educational attainment for affected children, particularly children of legal working age who dropped out of schools.

- 7 ^ It may make more sense to start with younger children if they are less likely to transmit the virus to others. In addition, the importance of early childhood education and social skill development may be less substitutable with virtual instruction, and younger children have a higher level of child care needs.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.