The Federal Reserve concluded its framework review last Thursday at the annual Jackson Hole Symposium with the adoption of flexible average inflation targeting (AIT). Going forward, the FOMC will aim for inflation moderately above 2 percent following periods when inflation has run persistently below 2 percent in order to average 2 percent over time.

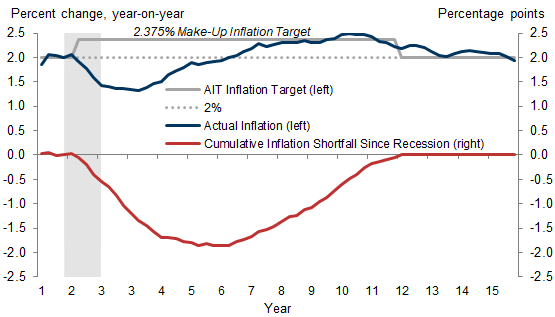

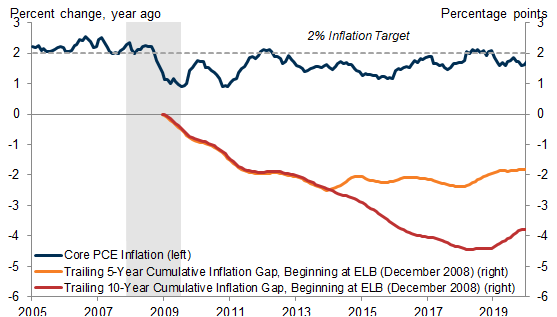

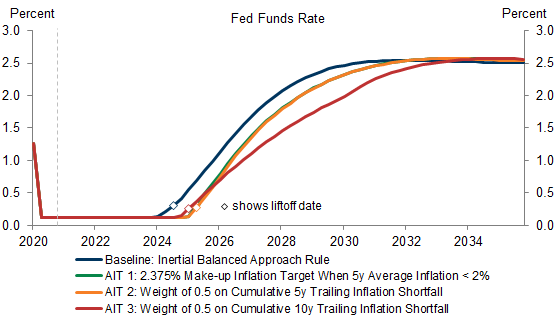

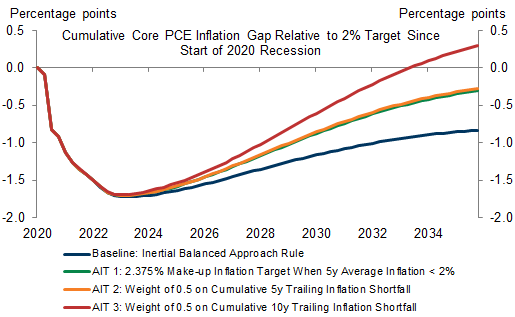

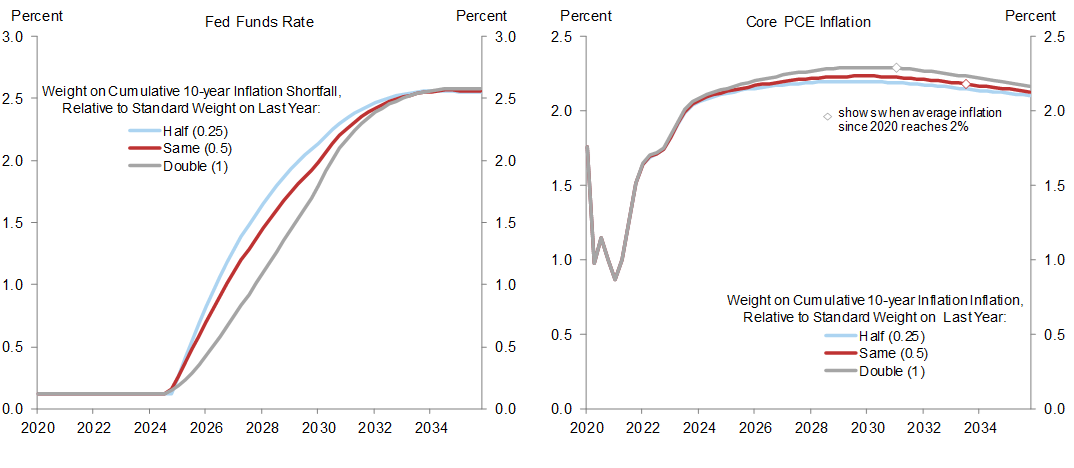

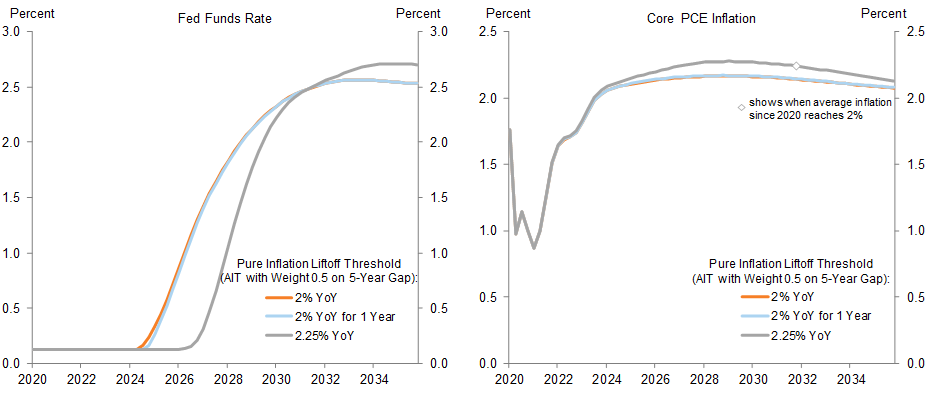

We see two straightforward interpretations of AIT as a modification to a standard Taylor rule reaction function. The first would temporarily raise the inflation target in the policy rule, say to 2¼-2½%, when average inflation over some trailing window falls short of 2%. The second would add the cumulative inflation shortfall over some trailing window, perhaps starting in a recession, as an additional term in the reaction function.

To explore what the new framework means for monetary policy and the economy, we use the Fed’s macroeconomic model, FRB/US, to run simulations that compare AIT policies with the old framework. We simulate these policies under current conditions using the baseline economic trajectory in FRB/US, which initially follows the FOMC’s June Summary of Economics Projections.

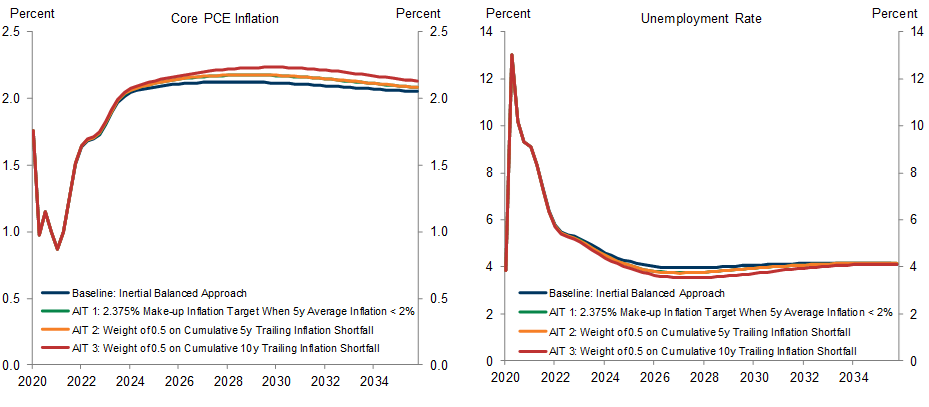

We draw three main conclusions. First, AIT rules appear roughly consistent with our forecast of liftoff around early 2025. Second, moderate AIT policies generate a moderately lower funds rate path and slightly higher inflation and lower unemployment than the old framework, but return average inflation to 2% very slowly. Third, an aggressive AIT policy with a 10-year lookback window generates a much lower funds rate path and somewhat larger economic effects, and returns average inflation to 2% in a little over a decade. These conclusions are sensitive to the baseline economic trajectory and the model's assumptions.

Our analysis also highlights some limitations of the new framework. Realistic macroeconomic models like FRB/US imply that when the policy rate is at the effective lower bound, lower-for-longer policies like AIT make only a limited incremental contribution to fighting recessions. Even with respect to their more limited ambition of stabilizing average inflation, AIT rules would likely require a quite long expansion to return average inflation to 2%, at least if the Phillips curve remains fairly flat.

The Fed’s New Framework

Two Interpretations of Flexible Average Inflation Targeting

What Average Inflation Targeting Means for Monetary Policy and the Economy

David Mericle

Laura Nicolae

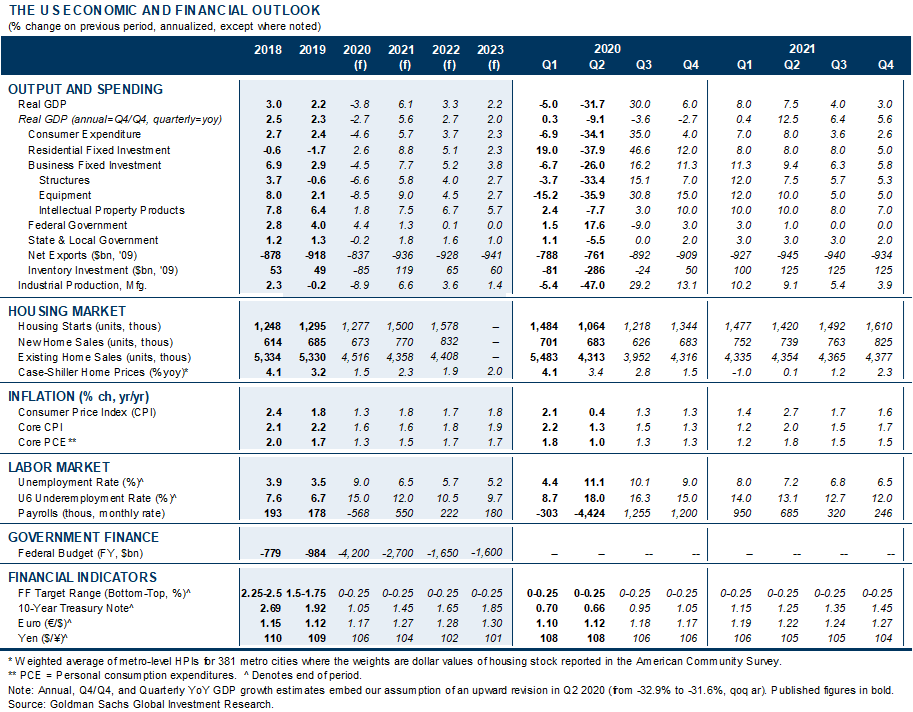

The US Economic and Financial Outlook

Forecast Changes

- 1 ^ We thank David Reifschneider and David Wilcox for sharing the materials behind their papers, “Average Inflation Targeting Would Be a Weak Tool for the Fed to Deal with Recession and Chronic Low Inflation,” November 2019, and “A Program for Strengthening the Federal Reserve’s Ability to Fight the Next Recession,” March 2020.

- 2 ^ The latest update of FRB/US has inflation returning to target more quickly than usual and somewhat ahead of the unemployment rate reaching its longer-run level. This likely explains why similar Fed staff analyses of AIT in the aftermath of a generic moderate recession, rather than in the current cycle specifically, have generally found that the funds rate would remain at the effective lower bound for even longer than in our results. In addition to the Reifschneider and Wilcox papers cited above, see Jonas Arias, Martin Bodenstein, Hess Chung, Thorsten Drautzburg, and Andrea Ra, “Alternative Strategies: How Do They Work? How Might They Help?” 2020.

- 3 ^ See David Mericle, “A New Challenge to Average Inflation Targeting,” US Daily, November 8, 2019, which discusses Reifschneider and Wilcox 2019, and “Fighting the Next Recession,” US Economics Analyst, September 29, 2019.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.