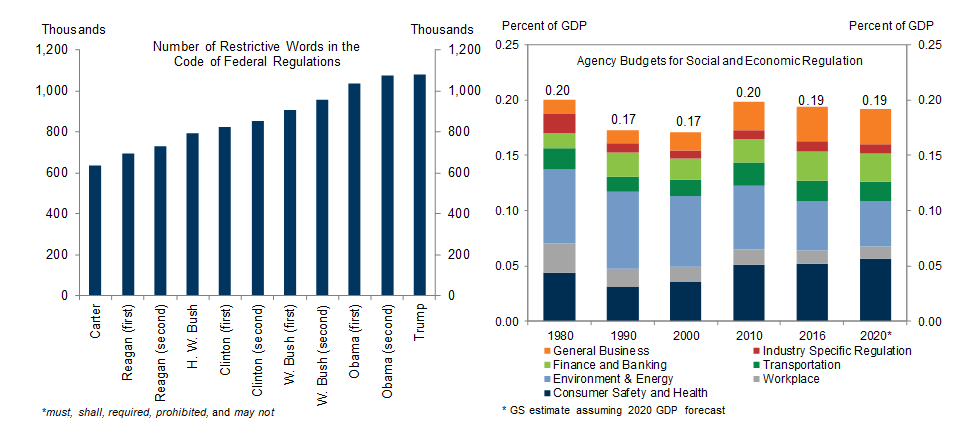

Over the past four years, the Trump administration advocated a broad deregulatory agenda with the goal of accelerating economic growth. The transition to the Biden administration raises the questions of how much deregulation mattered for the economy and what impact reversing these changes to regulatory policy might have.

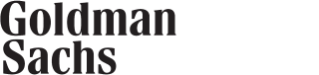

Several measures suggest that federal regulation stopped expanding but did not substantially decrease in the past four years. We assess the economic impact of the Trump administration’s regulatory policy changes using agency estimates, academic studies, and a bottom-up perspective from our equity analysts’ industry commentary. All of these sources suggest that the impact of regulatory policy changes over the last four years has been limited at a macroeconomic level.

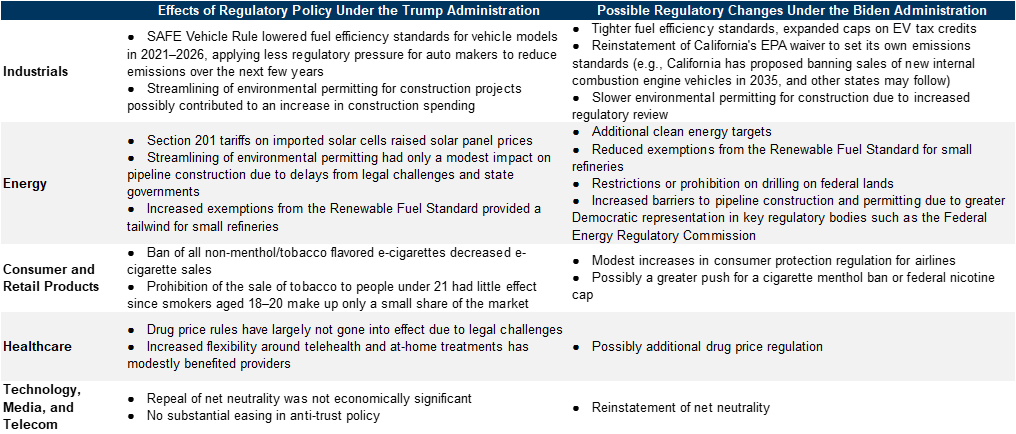

Looking forward, the Biden administration plans to reverse at least some of the Trump administration’s environmental deregulation. Possible changes include stricter fuel efficiency standards, increased renewable energy targets, increased environmental review of proposed infrastructure projects, and reduced exemptions from environmental standards for small fuel refineries. If implemented, these changes are likely to boost earnings for U.S. clean energy companies, have a neutral to slightly positive impact on many auto makers’ earnings, and lower earnings for small fuel refineries. At a macroeconomic level, the impact is likely to be modest.

Deregulation, Reregulation, and the Economy

Laura Nicolae

- 1 ^ Cary Coglianese, Natasha Sarin, and Stuart Shapiro, “Deregulatory Deceptions: Reviewing the Trump Administration’s Claims About Regulatory Reform,” Penn Program on Regulation, November 2020.

- 2 ^ The fiscal budget outlays devoted to developing and enforcing federal regulations

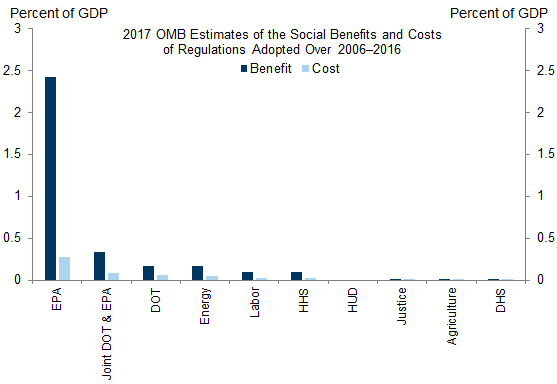

- 3 ^ Some measures suggest that regulation has decreased slightly. As we discuss later, the Office of Management and Budget’s own estimates find that regulatory compliance costs decreased by $198.6 billion (~1% of GDP) in net present value terms, implying an average cost reduction of about $13.9 billion (0.07% of GDP) each year.

- 4 ^ $ 2016

- 5 ^ Although this represents only a minority of new rules, the OMB estimates that the net benefits of the new major rules adopted over fiscal years 2017-2019 for which issuing agencies estimated both costs and benefits ranges from $2.1 billion annually to $9.5 billion annually.

- 6 ^ See Office of Management and Budget (2017), “2017 Report to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations and Agency Compliance with the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act.”The OMB estimates that the three rules adopted by the EPA during the Trump administration for which the agency estimated both benefits and costs had greater benefits than costs. However, some research suggests that agencies tend to overstate the benefits of their regulatory changes relative to costs, but it is unlikely that the benefits of environmental regulation are uniquely overstated relative to other kinds of regulation, implying that environmental regulation still likely has a higher benefit-cost ratio than other kinds of regulation. See Miller, Benjamin M., et al. (2017), “Inching Toward Reform: Trump’s Deregulation and Its Implementation,” RAND Corporation.

- 7 ^ See, for example, Ferris, Ann, Richard Garbaccio, Alex Marten, and Ann Wolverton (2017), “Working Paper: The Impacts of Environmental Regulation on the U.S. Economy,” Environmental Economics Working Paper Series, Environmental Protection Agency; Palmer, Karen, Wallace E. Oates, and Paul R. Portney (1995), “Tightening Environmental Standards: The Benefit-Cost or the No-Cost Paradigm?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(4).

- 8 ^ See also Cary Coglianese, Natasha Sarin, and Stuart Shapiro, “Deregulatory Deceptions: Reviewing the Trump Administration’s Claims About Regulatory Reform,” Penn Program on Regulation, November 2020.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.