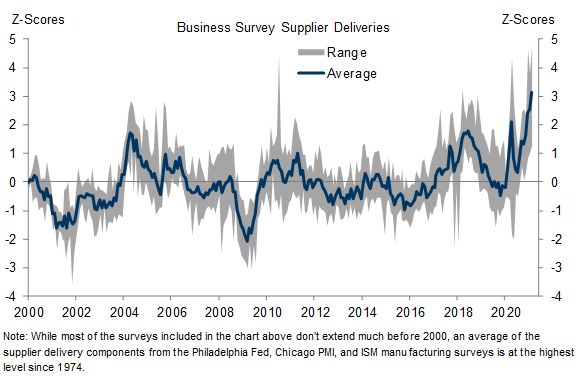

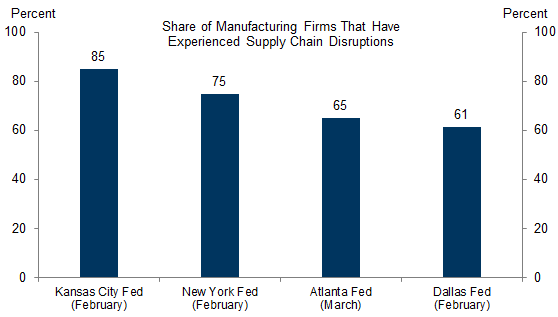

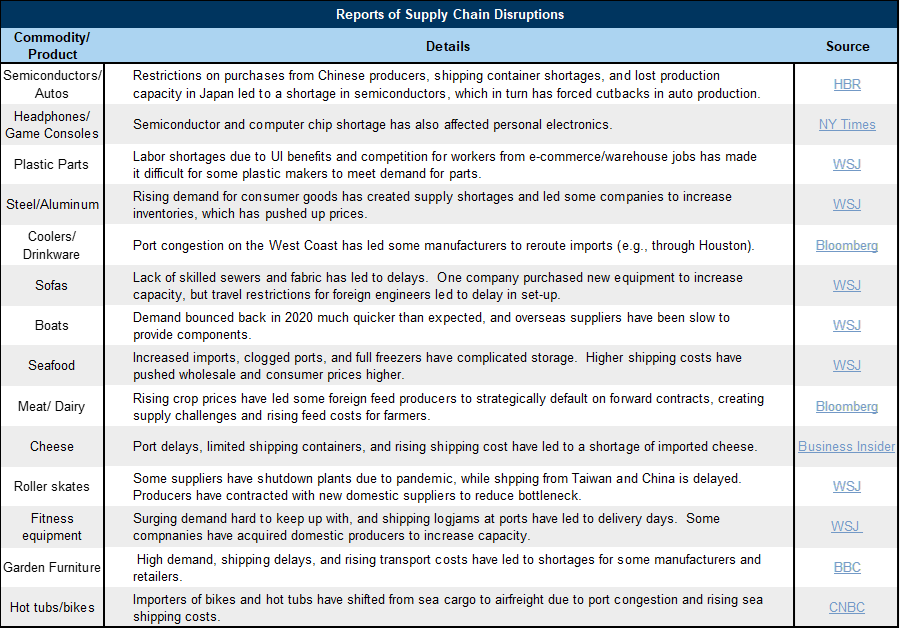

US manufacturers’ supply chains are increasingly strained, as a rapid recovery in goods demand combined with lingering pandemic-related constraints on international transport services has pushed delays in supplier deliveries to their highest level in over 40 years. As a result, a significant majority of manufacturing firms currently indicate that supply chain disruptions and delivery delays are negatively affecting production.

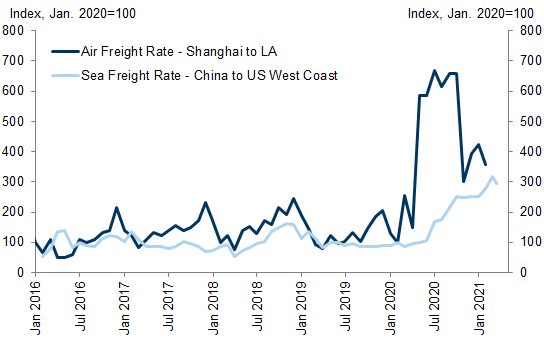

These supply challenges have significantly increased international shipping costs—particularly along routes from East Asia to the US, where shipping container prices have roughly tripled over the last year—and some of these cost increases will likely be passed on to consumers.

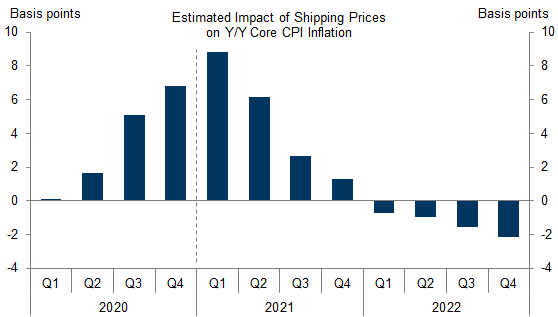

However, we expect a fairly limited impact on overall consumer prices for two reasons. First, shipping costs outside of East Asia have seen much smaller price increases. Second, total shipping costs represent only a small share of the final price of goods. As a result, we estimate that elevated shipping costs are currently boosting year-over-year core consumer price inflation by slightly less than 10bp.

Unfortunately, supply chain disruptions are unlikely to abate in the near term and will continue to put upward pressure on consumer prices for the rest of this year: fiscal stimulus will keep goods demand elevated and the virus will continue to disrupt the supply of international goods transport services. However, by early next year, we think that shipping bottlenecks are likely to resolve themselves and prices will moderate, turning the boost to core inflation into an outright drag.

The Inflation Boost From Supply Chain Disruptions: Here Today, Gone in 2022

Joseph Briggs

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ Including the New York, Kansas City, Dallas, and Atlanta Federal Reserve banks.

- 2 ^ Marcel Timmer, Erik Dietzenbacher, Bart Los, Robert Stehrer, and Gaaitzen de Vries,“An Illustrated User Guide to the World Input–Output Database: the Case of Global Automotive Production,” 2015.

- 3 ^ We assume a 50% pass-through rate of producer core goods prices to core consumer goods prices.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.