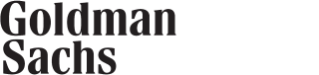

Federal Reserve Chair Powell has said that the tight labor market at the end of last cycle was narrowing economic disparities and “delivering life-changing gains,” particularly for people from low- and moderate-income communities. The FOMC incorporated this lesson into its new monetary policy framework and now says that maximum employment “is a broad-based and inclusive goal” that is assessed with a “wide range of indicators.”

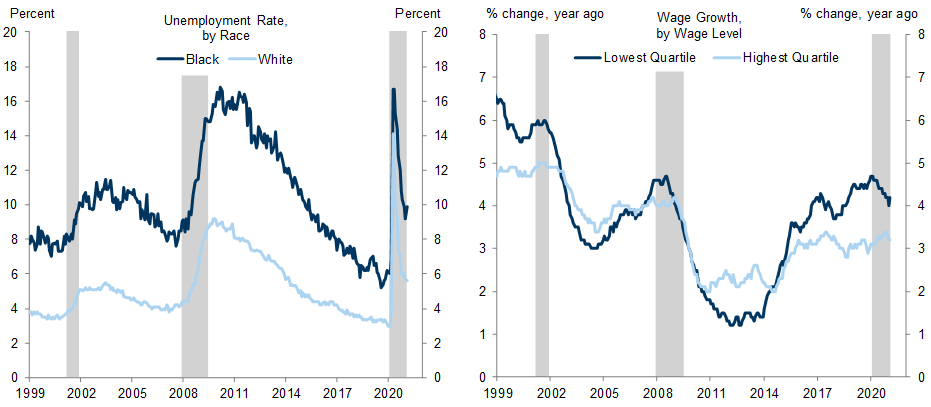

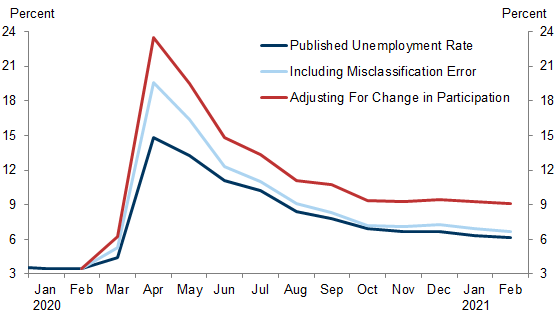

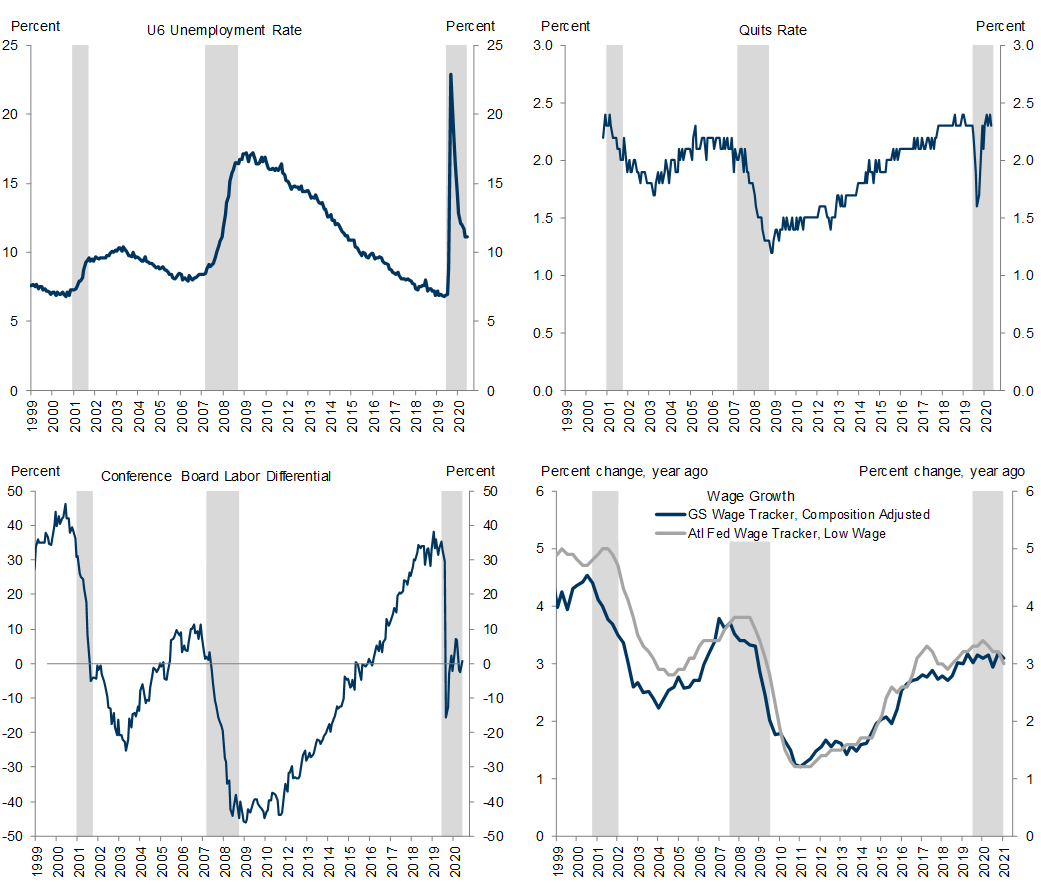

Fed officials increasingly emphasize the new broad and inclusive mandate when discussing the employment outlook. At the March FOMC press conference, Chair Powell cited the Black and Hispanic unemployment rates as among the “dozen things” that the FOMC looks at in addition to the overall unemployment rate. After collecting labor market indicators Fed officials have mentioned into an updated dashboard, we find that many suggest more slack than headline unemployment.

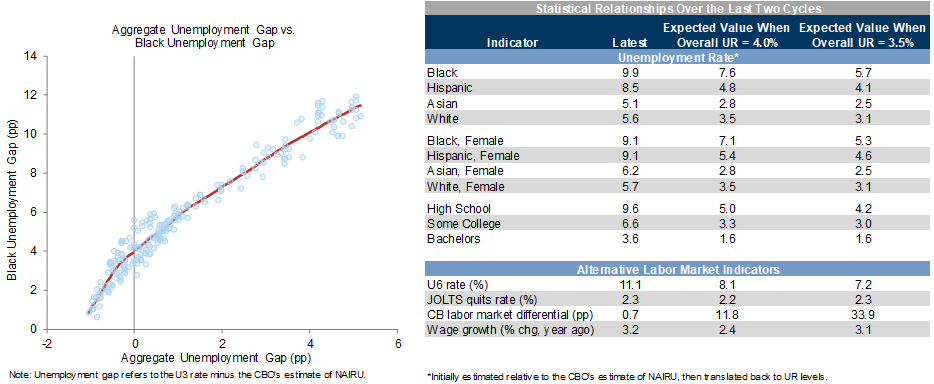

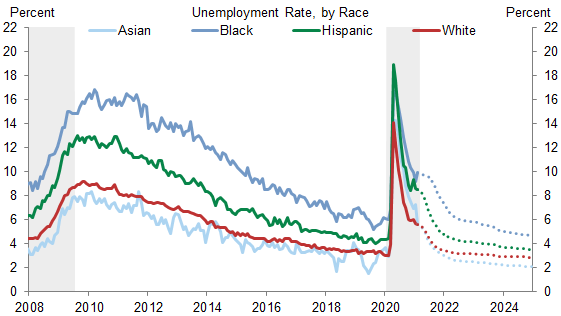

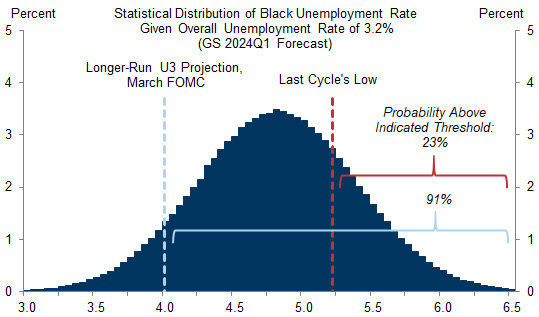

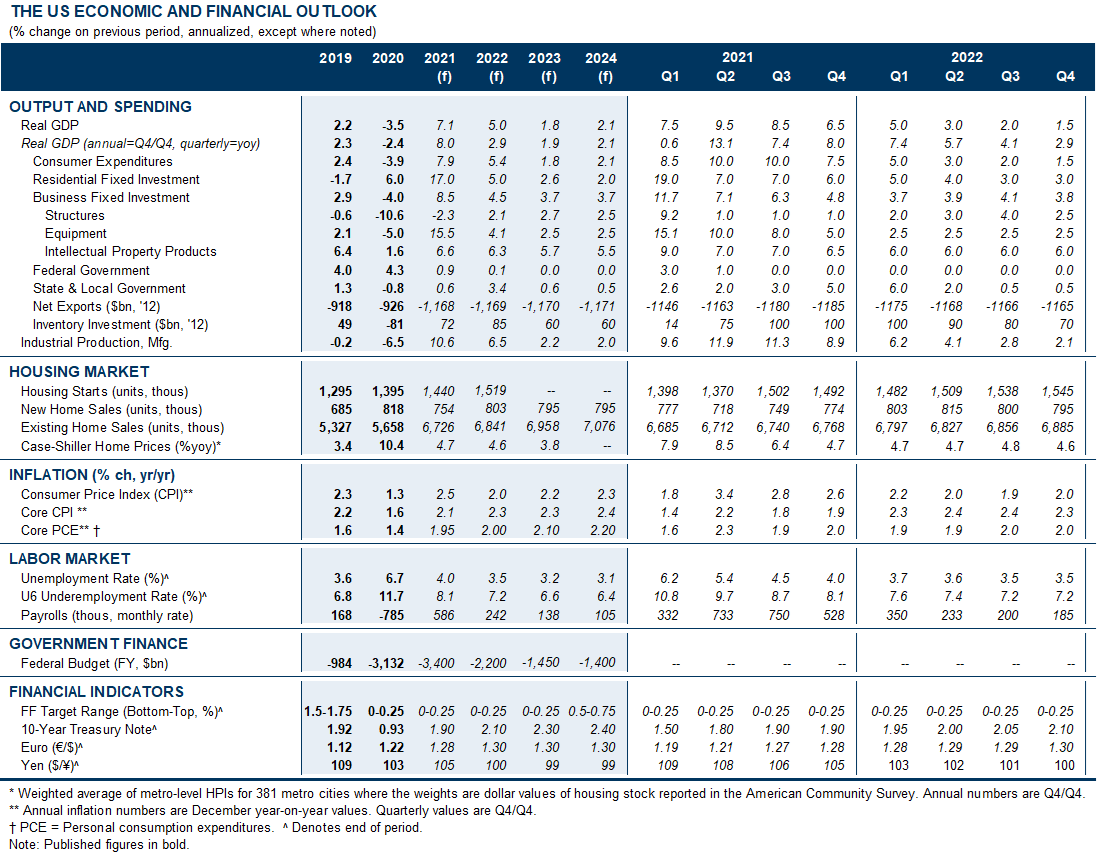

Interpreting the Fed’s new maximum employment goal is somewhat difficult because many indicators don’t have a familiar maximum employment benchmark. To aid interpretation, we estimate a level equivalent to maximum employment for several indicators based on their historical relationship with U3 unemployment. We also use our unemployment forecast and the relationship of individual indicators with U3 unemployment to project demographic-specific unemployment rates through 2024. While we forecast that the overall unemployment rate will fall below the FOMC’s longer-run estimate of 4% by early next year, historical statistical relationships suggest that some demographic groups’ unemployment rates will remain above 4% for much longer.

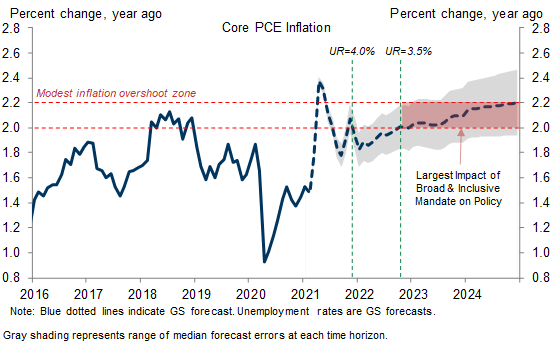

This new approach could have dovish monetary policy implications, though probably modest ones. It will probably not affect monetary policy when core PCE inflation is running below or well above 2%, since the Fed’s new inflation criteria rules out liftoff in the former case and the Fed would likely tighten policy in the latter case to keep inflation expectations anchored. However, it could affect policy decisions even after overall U3 hits the Fed’s longer-run goal if inflation is only modestly above 2% and stable. In this scenario, some FOMC members may prefer to wait for further improvement before raising the policy rate if unemployment for some demographic groups remains elevated.

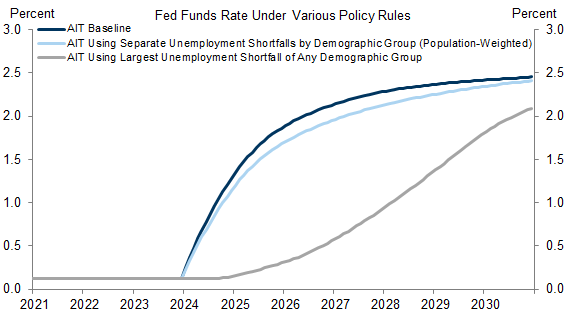

To provide a concrete interpretation of the new goal’s impact, we modify an average inflation targeting policy rule to also incorporate the broad and inclusive employment goal. This exercise implies that the broad and inclusive goal slows the pace of tightening only slightly, with a peak impact of -20bps, although more dovish interpretations of the new employment goal are also possible.

The Fed’s Broad and Inclusive Maximum Employment Goal

A Broad and Inclusive Employment Goal

Fed Commentary on Maximum Employment and the Broad and Inclusive Mandate

Date | Speaker | Key Quotes | Venue |

Mar 17 | Powell | We look at a very broad range [of labor market indicators]. You hear us talk all the time about participation, about employment to population, which is the combination of the two, about different measures of unemployment. So it’s wages. It’s the job flows. You know, all of those things go into an assessment of maximum employment. | |

Mar 5 | Kashkari | Maximum employment, for me, is a labor market that is tight enough that it generates 2 percent inflation on average over time. We had not yet achieved that before the pandemic hit. So, we need to get back to where we were before the pandemic, but then we need to go beyond it to really put all Americans back to work. | |

Feb 24 | Brainard | 1. I would not recommend relying on any single indicator, but rather consulting a variety of indicators that together provide a holistic picture of where we are relative to full employment. 2. [In addition to unemployment rates by wage-level] There is also important information in the disaggregation of unemployment by different racial and ethnic groups. 3. While the EPOP ratio is a strong indicator of the extensive margin in the labor market, or how many people are working, there is also important information in the intensive margin—that is, how much work each person is doing. | |

Feb 23 | Powell | We emphasize that maximum employment is a broad and inclusive goal. This change reflects our appreciation for the benefits of a strong labor market, particularly for low- and moderate-income communities. | |

Feb 19 | Rosengren | 1. The pandemic has had significantly divergent impacts on different industries and workers, leading to very different economic outcomes across different segments of the population. 2. My view is that policymakers must work to ensure that the benefits of the eventual recovery are widely shared. | |

Feb 10 | Powell | Given the number of people who have lost their jobs and the likelihood that some will struggle to find work in the post-pandemic economy, achieving and sustaining maximum employment will require more than supportive monetary policy. It will require a society-wide commitment, with contributions from across government and the private sector. | |

Jan 7 | Daly | There's a danger in computing a [single indicator] and saying that means we are there. | |

Nov 16 | Clarida | [Maximum employment] means to me that, when the unemployment rate is elevated relative to my SEP projection of its long-run level and other indicators—such as the prime-age employment-to-population and labor force participation ratios—are depressed relative to recent business cycle peaks, monetary policy should, as before, continue to be calibrated to eliminate such employment shortfalls as long as doing so does not put the price-stability mandate at risk. | |

Oct 2 | Harker | Tolerating the risk of slightly higher inflation, in our view, is worth it if it helps us achieve our employment goals. That’s important because one of the salutary trends of the pre-COVID economy was that economic gains, at least on a limited basis, were finally being enjoyed by lower-wage workers, a disproportionate percentage of whom are racial minorities. We still had a very, very long way to go, of course. But it’s clear that we must achieve full employment to have any hope of beginning to narrow the yawning gaps that bedevil our society. | |

Sep 29 | Kaplan | [Unemployment rates by demographic group] reinforce the need for greater efforts to invest in education and skills training in order to create a stronger and more inclusive labor market and help ensure that key groups of our society are not left behind in this recovery. | |

Sep 16 | Powell | 1. [When asked if the Fed is open to using specific measures of inequality in setting monetary policy] The thing is, we don’t really have the tools to address those. We have interest rates and bank supervision and financial stability policy and things like that, but we can’t get at those things through our tools. When we lower the federal funds rate, that supports the economy across a broad range of, of people and activities, but we don’t have the ability to target particular groups. 2. When we think about maximum employment in particular, we do look at individual groups. So high unemployment in a particular racial group like African Americans, we would look at that as we think about whether we’re really at maximum employment. We would look at that along with a lot of other data. So the answer is, we do look at all those things and, and do what we can with our tools. But, ultimately, these are issues for elected representatives. | |

Jul 16 | Bostic | From Reuters interview recap: "Bostic … 'could imagine' a day when the unemployment rate for Blacks gets highlighted in Fed statements as a way to measure the true strength of the labor market. | |

Jun 17 | Kashkari | I don’t think we have the ability to say “we’re going to target a reduction in this type of inequality through interest rates.” But I do think paying attention to these [racial] disparities gives us better insight into labor market slack in general. | |

Jun 12 | Bostic | 1. I believe the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and the Federal Reserve more generally, can play an important role in helping to reduce racial inequities and bring about a more inclusive economy. 2. We can do this, first, by fulfilling the mission given to us, which is to promote the health of the U.S. economy and the stability of the U.S. financial system. 3. The second way the Atlanta Fed can contribute to a more inclusive economy lies in the foundation of promoting maximum employment, by addressing the economic inequality that persists in this country. |

What the Fed is Watching

Assessing Maximum Employment Under the New Broad and Inclusive Goal

The Monetary Policy Implications of the New Broad and Inclusive Goal

Joseph Briggs

Ronnie Walker

Laura Nicolae

- 1 ^ Jerome Powell, “New Economic Challenges and the Fed's Monetary Policy Review,” 2020.

- 2 ^ See also Clarida and Kaplan.

- 3 ^ For additional work on the benefits of tight labor markets, see David Choi “US Daily: Tight Labor Markets: Do Lower-Skilled Workers Benefit More?” 2019 and David Choi “US Daily: Labor Force Participation: Revisiting the Role of Disabled Workers,” 2019.

- 4 ^ For a detailed overview of the economic challenges faced by Black women, see Daan Struyven, Gizelle George-Joseph, and Dan Milo, “Black Womenomics” 2020.

- 5 ^ Lael Brainard, “How Should We Think about Full Employment in the Federal Reserve's Dual Mandate?” 2021.

- 6 ^ Stephanie Aaronson, Mary Daly, William Wascher, and David Wilcox “Okun revisited: Who benefits most from a strong economy?” 2019.

- 7 ^ We make two additional adjustments to the standard monetary policy rule in our analysis. First, based on recent comments from Fed officials, we interpret the U3 unemployment rate corresponding to maximum employment as 3.5%. Second, we constrain liftoff until our core PCE inflation forecast crosses the Fed’s liftoff threshold in 2024.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.