In economic terms, the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic is often compared to a war – national resources have been commandeered in a battle against an ‘invisible enemy’, driving government debt levels sharply higher around the world. To see how far this analogy can be extended, we use data extending back to the Black Death in the 1300s to compare how inflation and government bond yields have behaved in the aftermath of the world’s 12 largest wars and pandemics.

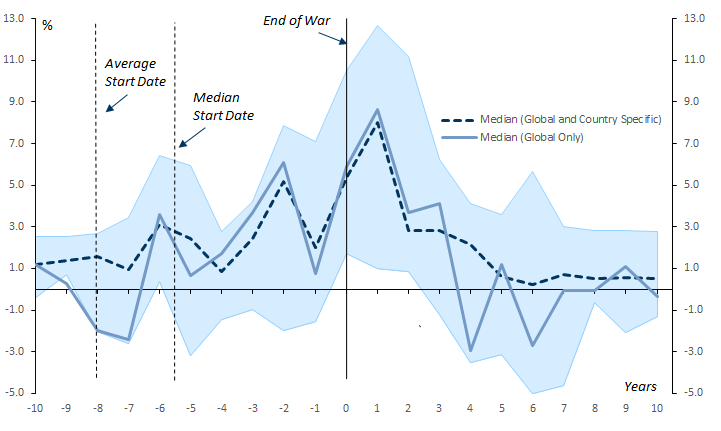

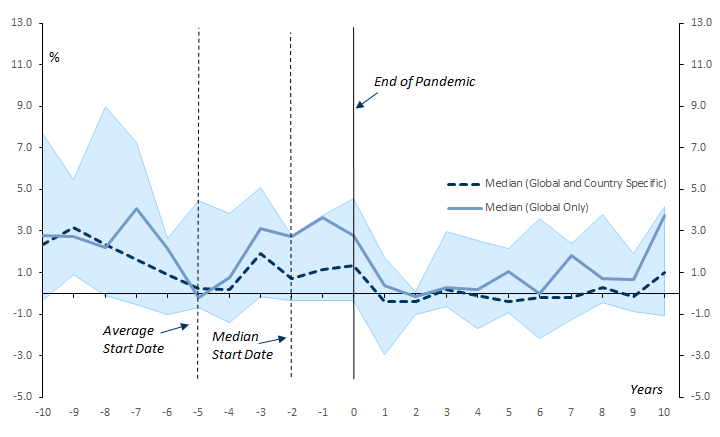

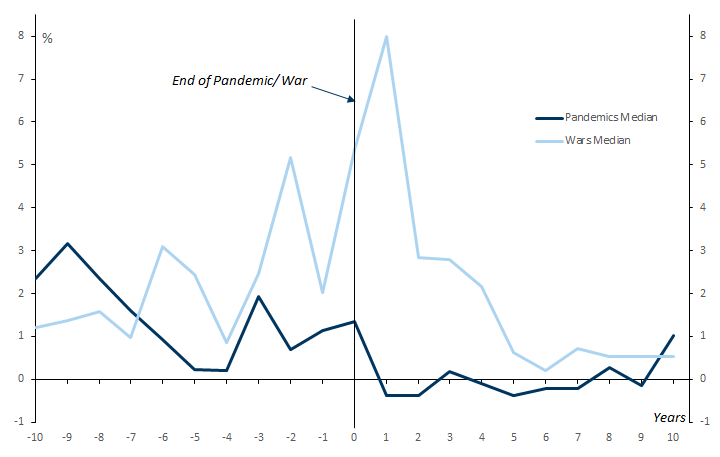

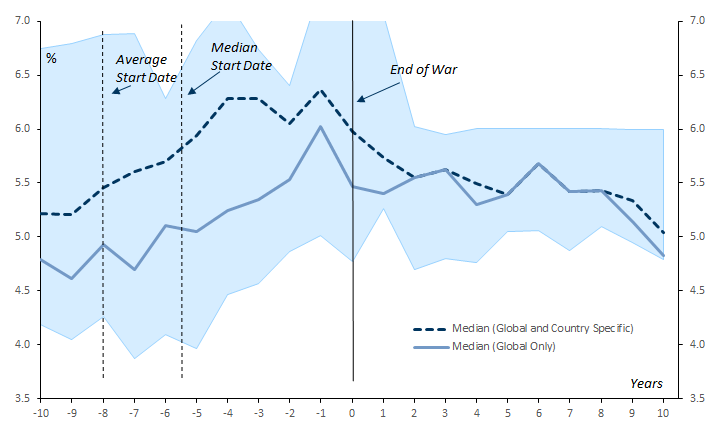

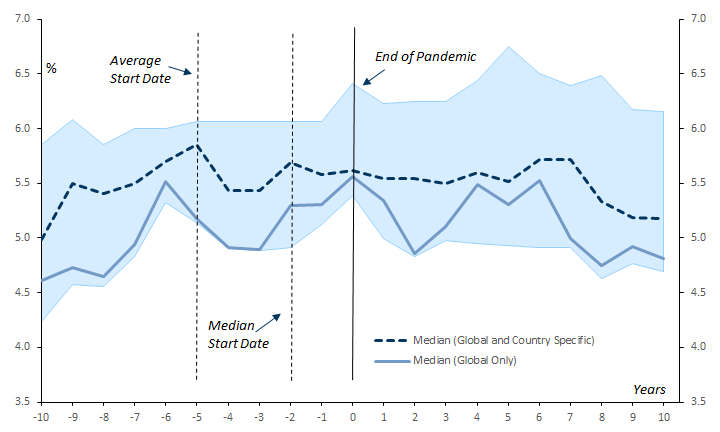

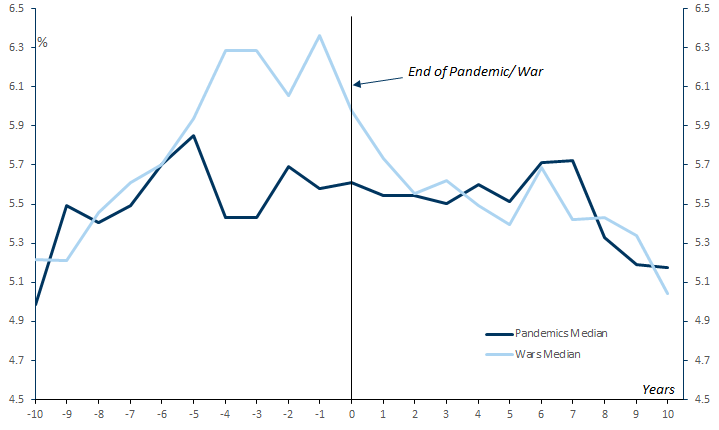

We find that, while inflation has typically risen sharply during and (especially) in the aftermath of major wars, it has generally remained weak during and after major pandemics. Moreover, while bond yields have typically risen during wars, they have remained relatively stable during pandemics and fallen in their aftermath.

In our view, this contrast in the performance of inflation and bond yields during wars and pandemics makes intuitive sense, for two reasons: First, in wars, government spending is used to fund increased war-related expenditure (before and during wars) and reconstruction efforts (in the aftermath), placing significant strain on available resources. In pandemics, by contrast, any increase in government spending is used to fill the gap left by absent private sector demand, with very different implications for the overall balance between aggregate demand and supply. Second, wars are often associated with the widespread destruction of physical capital, a development that increases the demand for investment and pushes interest rates higher. While pandemics result in a widespread loss of life, they do not result in any loss of physical capital.

Every war and pandemic is different, and we should be cautious of drawing lessons from events that occurred in the long-distant past and in very different circumstances. One feature of the current pandemic that is clearly distinctive to past episodes is the size of the government response. Equally, however, one can argue that an unusually large government response was necessitated by an unusually large collapse in private sector demand.

What is clear is that history provides no evidence that higher inflation or higher bond yields are a natural consequence of major pandemics.

Inflation in the Aftermath of Wars and Pandemics

The ‘War’ Against COVID-19

From COVID-19 to the Black Death — Very Long-Run Data on Inflation and Bond Yields

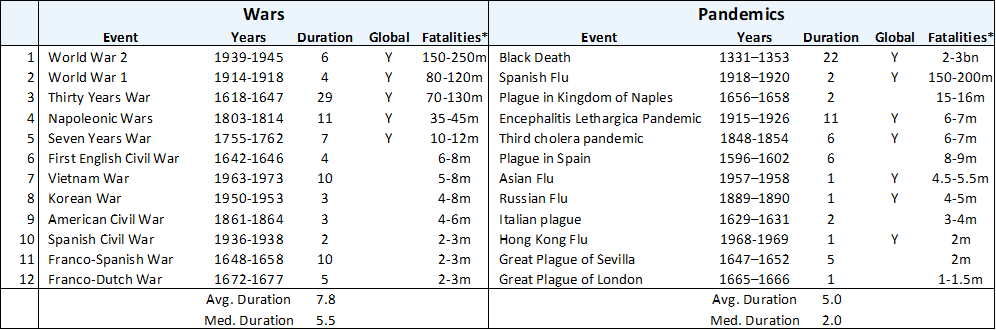

Exhibit 1: Our Sample of Major Wars and Pandemics

Wars Result in Higher Inflation and Bond Yields, Pandemics Do Not

Why Wars Are Different from Pandemics — Wars Result in Overheating and the Destruction of Physical Capital

Wars drive aggregate demand higher, while pandemics drive aggregate demand lower: In wars, there is a long history of using debt-financed spending to fund increased war-related expenditure (before and during wars) and reconstruction efforts (in the aftermath), driving aggregate demand higher relative to war-damaged supply. In pandemics, by contrast, any increase in government spending is used to fill the gap left by absent private sector demand, with very different implications for the overall balance between aggregate demand and supply.[6]

Wars destroy physical capital, driving investment and interest rates higher: Wars are often associated with the widespread destruction of physical capital, a development that increases the demand for investment and pushes interest rates higher. By contrast, pandemics do not result in any loss of physical capital and, if there is widespread loss of life, can result in an increase in the capital-labour ratio. Standard economic theory suggests that a higher capital-labour ratio should lower equilibrium interest rates, while raising real wages.[7]

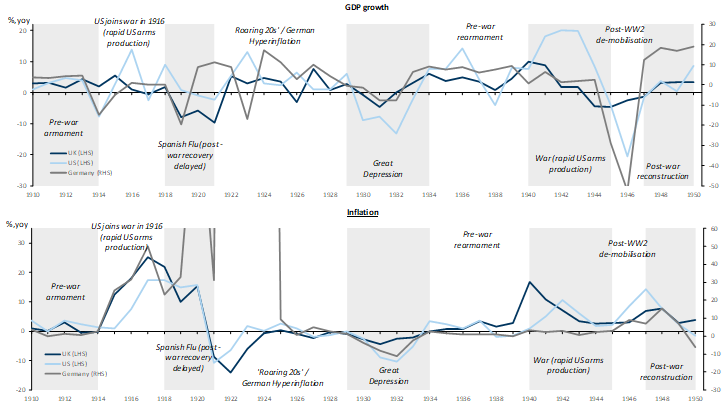

Lessons from the Past: From the World Wars to the Black Death

World War I (1914-18): The years leading up to the outbreak of war were characterised by relatively rapid growth, partly fuelled by a rapid military expansion by European powers (Exhibit 8). Inflation accelerated sharply across Europe from 1914 onwards, as the UK, Germany and France were forced to abandon the Gold Standard, rising to a peak of 50%yoy in Germany and 25%yoy in the UK in 2017. The US did not join the war until 1916 and growth and inflation both accelerated sharply in that year, with GDP rising 14%yoy and inflation reaching 17%yoy in 1917.

The Spanish Flu (1918-1920) is estimated to have killed around 40-50 million people worldwide, or 2-2½% of the world’s population, around twice the number that died during World War I. While growth and inflation both weakened during the pandemic (Exhibit 8), it is difficult to determine from time series data alone whether this was due to the war ending or the pandemic. To distinguish between these effects, Barro, Ursua and Weng (2020) use cross-sectional data on war and flu deaths.[8] On this basis, they estimate that the Spanish Flu reduced real GDP per capita by 6% on average and that, in contrast to the highly inflationary effects of World War I, the pandemic had a “negligible” impact on the price level.

World War II: In common with WWI, the years leading up to WWII were also characterised by relatively strong growth which, in Europe, was partly fuelled by rapid military expansion. Inflation accelerated sharply in the UK in 1939-40, as war was initially declared, and later in the US, as it subsequently joined the war (Exhibit 8). During the war years, GDP growth was exceptionally strong in the US (boosted by a significant increase in arms production and without the cost of war damage) but weaker in Europe (where governments strained to maintain arms production amid widespread war damage). Inflation remained high throughout the war years and through the initial post-war period, before declining in 1949/1950.[9]

Napoleonic Wars: As tensions rose between England and France ahead of the Napoleonic Wars, the UK government tripled government spending over a five-year period (1792-97), partly funding this increase through a depletion of the Bank of England’s gold reserves (Broadbent (2020)). Fears over the impending war resulted in a private sector switch from Bank paper into gold, causing the government to suspend gold convertibility. The price level subsequently rose by 59% over the following 3 years, although it stabilised thereafter and gold convertibility was subsequently restored in 1821.

The Black Death: The bubonic plague reached England in late 1348 and, over the subsequent 3 years, resulted in a 30-45% reduction in the country’s population. As Jordà, Singh and Taylor (2020) discuss, the sharp reduction in labour was the primary cause of the Peasants' Rebellion, a doubling of real wages, and a significant reduction in rates of return on land.

Higher Inflation is Not a Natural Consequence of Pandemics

- 1 ^ See "A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data", Bank of England Research Datasets and Schmelzing, 2020, “Eight centuries of global real interest rates, R-G, and the ‘suprasecular’ decline, 1311–2018”, Bank of England Working Paper No. 845.

- 2 ^ Some economists have attempted to construct very long-run historical estimates of other economic variables, such as GDP (see, for example, Maddison (2020)). However, in contrast to data that we use on prices and bond yields, these estimates are not measured directly and rely on some pretty strong assumptions (not least because the concept of GDP did not exist before the 1930s).

- 3 ^ As the end-year for wars and pandemics (Year = 0), we use the last year of significant fatalities. In a number of instances, this is one year before the formal end of the war/pandemic.

- 4 ^ For example, for the Franco-Spanish war of 1648-1658, we consider only French and Spanish data. Note that, in the exhibits below, we also display results focusing only on global wars and pandemics.

- 5 ^ Ideally, we would also consider ex ante real bond yields, but for this we would need a long-run history of inflation expectations. One can calculate a simple measure of real yields by subtracting current inflation but, because inflation typically rises sharply during wars, this has the effect of pushing real yields lower.

- 6 ^ A similar argument has previously been made by Broadbent (2020), who argues that institutional quality is a more important determinant of inflation than the rise in debt (Broadbent (2020), “Government debt and inflation”, Bank of England speech).

- 7 ^ Jordà, Singh and Taylor (2020) also make this argument and find that pandemics tend to reduce r* or the equilibrium interest rate (Jordà, Singh and Taylor (2020), “Longer-run Economic Consequences of Pandemics,” NBER Working Paper No. 26934).

- 8 ^ Barro, Ursua and Weng (2020), “The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity”, NBER Working Paper No. 26866.

- 9 ^ The US's post-WWII experience is discussed in "Pent-Up Savings and Inflation After World War 2", US Daily, 25 February 2021.

- 10 ^ One can list many other differences between the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics. However, the differences that are likely to be most relevant for the medium-term inflation outlook are those that affect the relative balance between demand and supply and, in our view, those differences appear to have broadly offsetting effects. In particular, relative to past pandemics, there has been a greater willingness through COVID to lower activity through lockdowns/restrictions, implying a larger short-term collapse in private demand and more short-term downward pressure on inflation. Set against this, there has also been a greater willingness to offset this shortfall through larger government income replacement.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.