The overheating debate has cast a spotlight on earlier episodes in US history when inflation rose sharply in a booming economy. We recently looked at the inflation surge after World War 2 and concluded that it was a unique event caused by factors with little contemporary relevance. Today we discuss the other major modern US example of high inflation, the 1960s and 1970s.

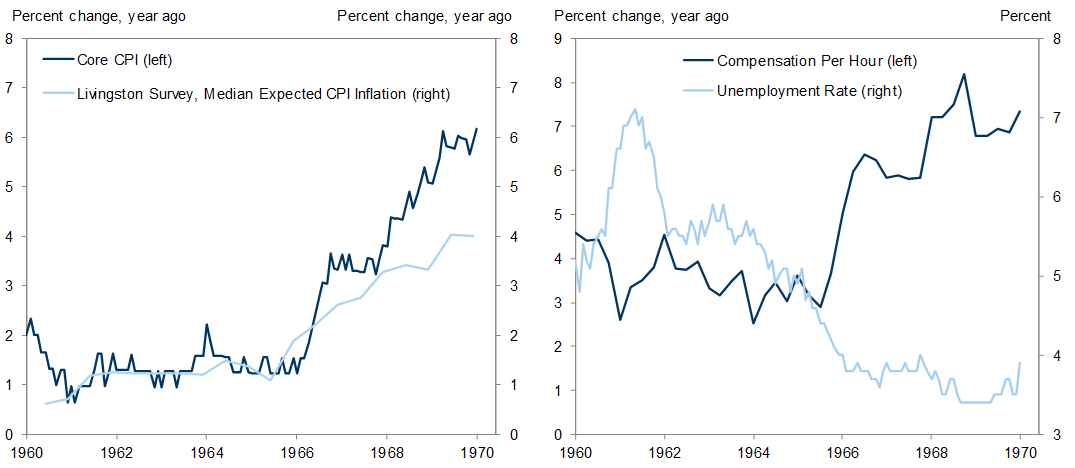

Inflation and inflation expectations were low and stable in the first half of the 1960s. But in the second half of the decade, the labor market became very tight as fiscal policy turned quite expansionary and monetary policy remained inappropriately easy. Wage growth and inflation spiraled upward as inflation expectations became unanchored and followed close behind.

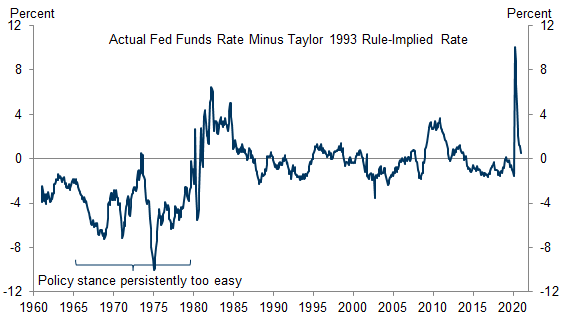

What went wrong? First, policymakers had a flawed framework: they initially thought that they could permanently lower the unemployment rate by tolerating higher inflation, and later they persistently underestimated NAIRU and too readily dismissed high inflation as temporary rather than as evidence of overheating. Second, the Fed was too hesitant to hike, at times because it worried about overtightening and at times because it thought fiscal measures would be enough to solve the inflation problem. Third, the Fed faced heavy political pressure.

How relevant is this episode to inflation fears today? There are some parallels: there will always be some uncertainty about the sustainable rate of unemployment or the slope of the Phillips curve at very low unemployment rates, bringing inflation down will always come at a high social cost, fiscal policy has again turned highly expansionary, and policymakers have again adopted an aggressive definition of maximum employment. But three key differences with the past make a repeat very unlikely today. First, the era of successful inflation targeting has better anchored inflation expectations on the Fed’s target, making inflation less persistent as a result. Second, having learned from past mistakes, Fed officials see keeping inflation expectations anchored as a paramount goal and monitor them actively with a wide range of measures. Third, politicians better understand the cost of high inflation and the importance of central bank independence.

Inflation and Overheating in the 1960s and 1970s

David Mericle

Laura Nicolae

- 1 ^ The Congressional Budget Office and the Fed estimate that NAIRU was 5.5-5.9% in the 1960s and is 3.5-4.5% today. Shifts in demographic, industrial, and occupational composition are among the reasons for the decline.

- 2 ^ See J. Bradford DeLong, “America’s Peacetime Inflation: the 1970s,” 1997; Christina Romer and David Romer, “The Evolution of Economic Understanding and Postwar Stabilization Policy,” 2002; Athanasios Orphanides, “The Quest for Prosperity Without Inflation,” 2003; Athanasios Orphanides, “Monetary Policy Rules, Macroeconomic Stability, and Inflation: A View from the Trenches,” 2004; Allan Meltzer, “Origins of the Great Inflation,” 2005; Athanasios Orphanides and John Williams, “Monetary Policy Mistakes and the Evolution of Inflation Expectations,” 2013; Andrew Levin and John B. Taylor, “Falling Behind the Curve: A Positive Analysis of Stop-Start Monetary Policies and the Great Inflation,” 2013; Harold James, Markus Brunnermeier, and Jean-Pierre Landau, “Who’s Right on Inflation?” 2021; and Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl, “The Financial Origins of the Rise and Fall of American Inflation,” 2020. There is some disagreement among these authors about which of the problems discussed here were most important.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.