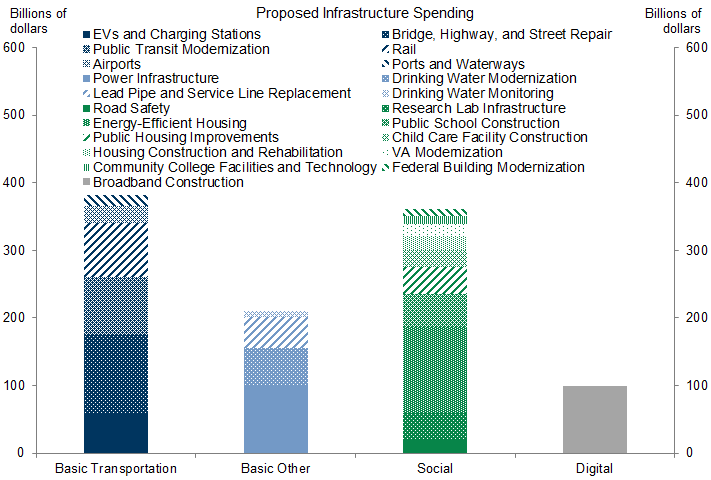

The White House’s American Jobs Plan proposes a variety of infrastructure investments ranging from transportation and electricity to social and digital infrastructure, and we expect most of them to be enacted. This week’s Analyst provides an overview of infrastructure economics.

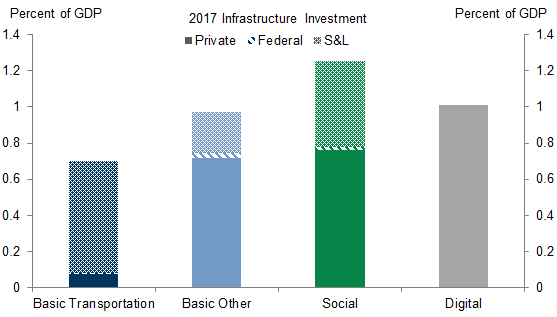

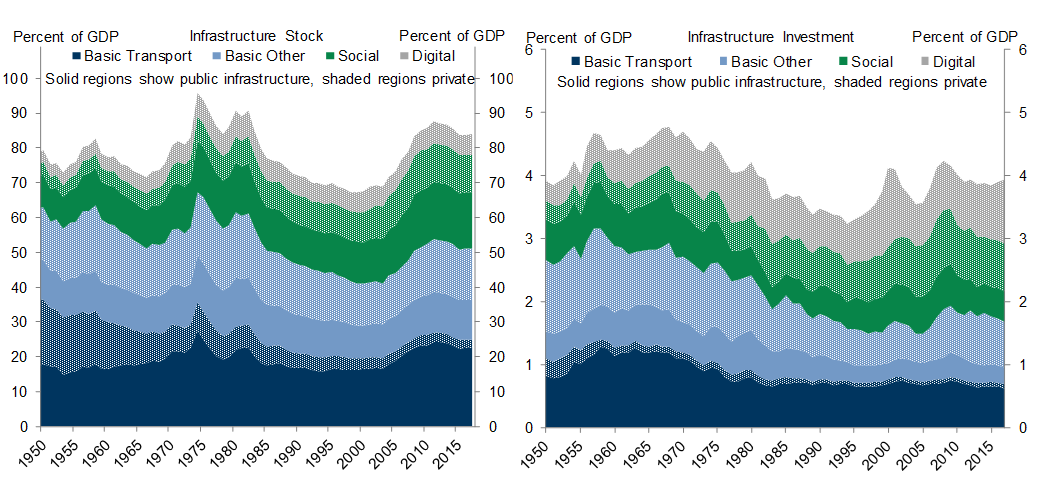

Policy debates often assume that prolonged underinvestment has left US infrastructure in poor shape. But is this really true? New official statistics introduced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis last year show that both the total stock of US infrastructure as a share of GDP and the flow of new investment are near average historical levels, though the composition has changed. The private sector plays a larger role in new investment, and rising social and digital infrastructure investment have offset a decline in basic infrastructure investment.

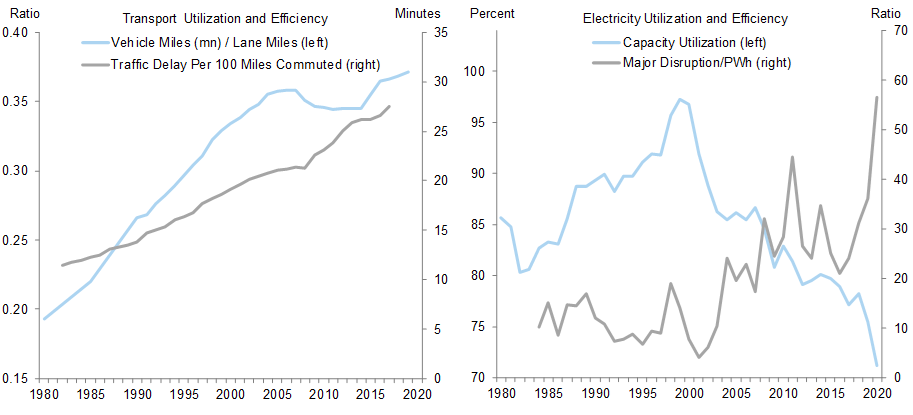

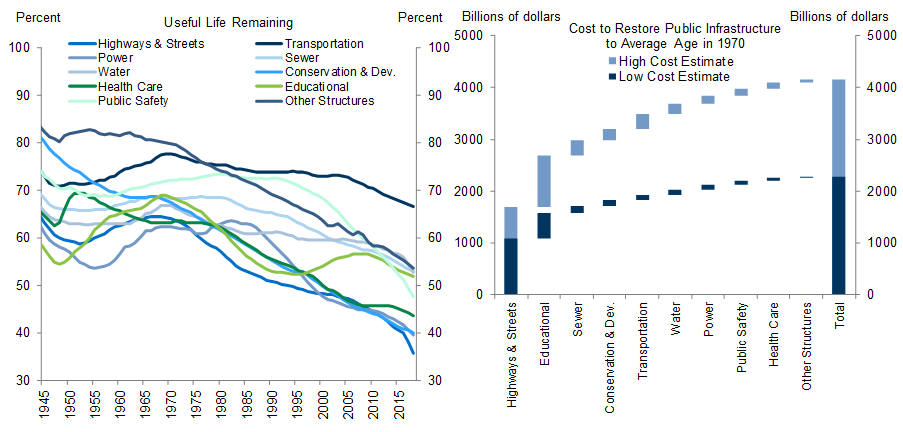

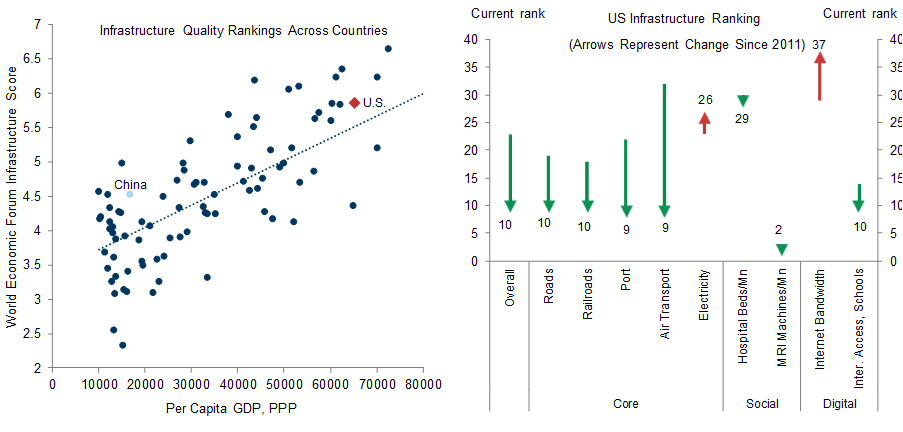

Measures of infrastructure quality and health are mixed. Core transportation and power generation infrastructure is aging and increasingly strained by demand. But the US scores reasonably well on international rankings of infrastructure quality, at least in most areas. Overall, the evidence suggests that while US infrastructure is not in as dire shape as sometimes claimed, there are areas of weakness and opportunities for improvement.

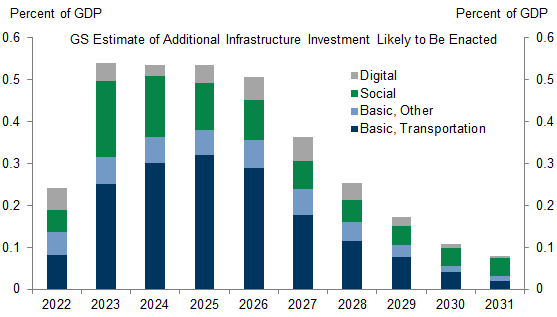

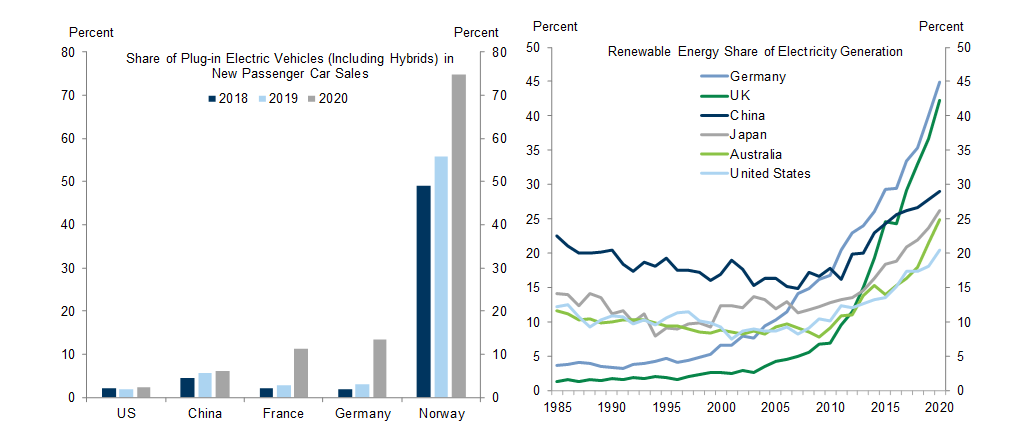

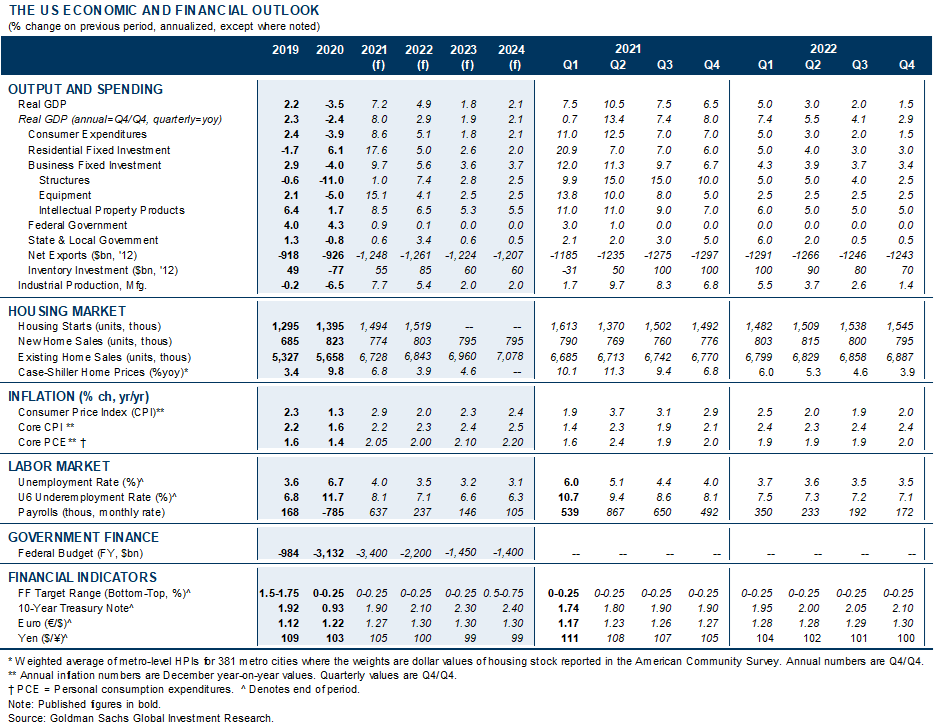

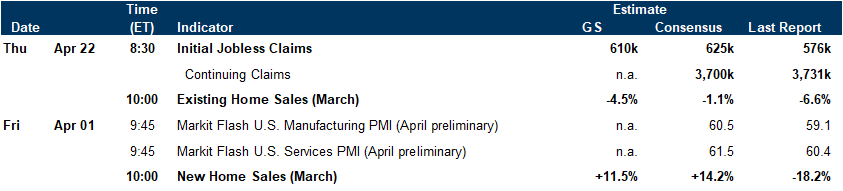

Infrastructure spending from the Biden plan would peak at around 0.5% of GDP from 2023-2026. The new spending would raise total infrastructure investment to around 4.5% of GDP, the highest level since the early 1970s. Infrastructure is only one part of the next round of fiscal measures, which we expect will add about 1% to the level of GDP in total in coming years.

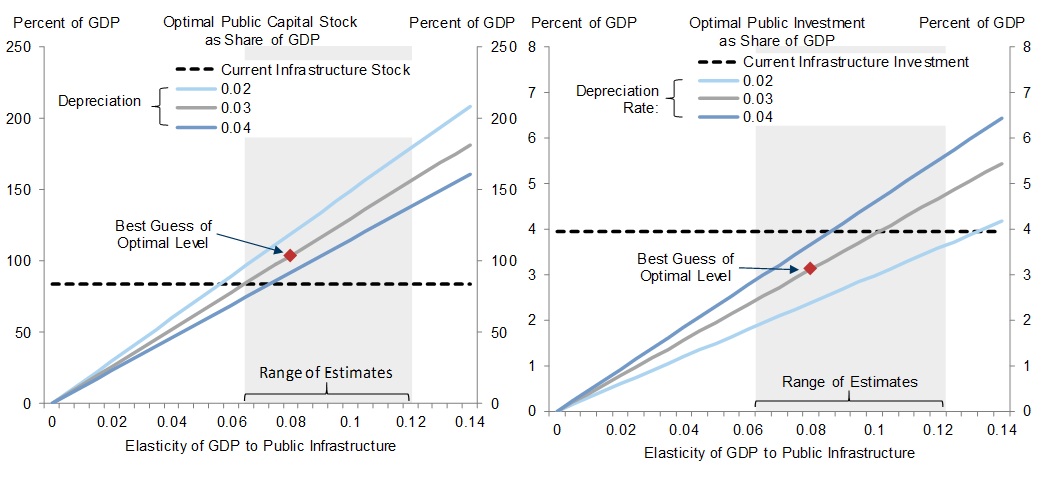

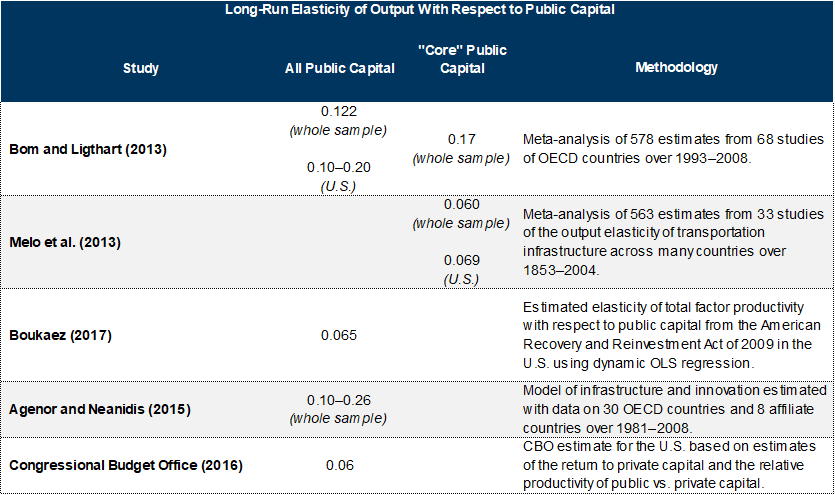

The impact of infrastructure investment on long-run potential GDP is more uncertain. Studies suggest that a 1% increase in the public capital stock raises the level of long-run output by about 0.1%, with somewhat larger effects from core infrastructure than from other projects. These numbers imply that the White House infrastructure proposals would eventually boost the level of potential GDP of about ½%. This estimate does not include the potential effects of other proposed fiscal measures such as research and development funding or new social benefits, nor of course does it capture the environmental benefits of the American Jobs Plan.

Infrastructure Economics

Defining Infrastructure

The State of US Infrastructure

The Infrastructure Package and GDP

Joseph Briggs

David Mericle

Laura Nicolae

- 1 ^ Jennifer Bennett, Robert Kornfeld, Daniel Sichel and David Wasshausen, “Measuring Infrastructure in the Bureau of Economic Analysis National Economic Accounts,” December 2020.

- 2 ^ The public share of the infrastructure stock is actually above its historical average (59% current vs. 55% historical), but this primarily reflects the relative decline in private capital held in railroads, which are included in the private basic transport region of Exhibit 3.

- 3 ^ Matthew Tuner and Geetika Nagpal, “Transportation Infrastructure in the US,” 2019.

- 4 ^ Valerie A. Ramey, “The Macroeconomic Consequences of Infrastructure Investment,” 2020.

- 5 ^ John Fernald, “Roads to Prosperity? Assessing the Link Between Public Capital and Productivity,” 1999.

- 6 ^ Edward Glaeser and James Poterba, “Economic Analysis and Infrastructure Investment,” 2020.

- 7 ^ Pierre-Richard Agénor and Kyriakos C. Neanidis, “Innovation, Public Capital, and Growth,” 2015; Hafedh Boukaez et al., “Public Investment, Time to Build, and the Zero Lower Bound,” 2017.

- 8 ^ The CBO estimates that a $1 increase in the federal deficit decreases private investment by about 33 cents. See Jeffrey M. Stupak, “Economic Impact of Infrastructure Investment,” Congressional Research Service, 2018.

- 9 ^ Estimates for the U.S. range from 0.06 to 0.20, but larger estimates tend to come from studies of older projects that likely had higher returns than current and future projects. Overall, estimates of the long-run output elasticity with respect to the public capital stock have declined over time. See Pedro Jenny Bom and Ligthart, “What Have We Learned from Three Decades of Research on the Productivity of Public Capital?” 2013.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.