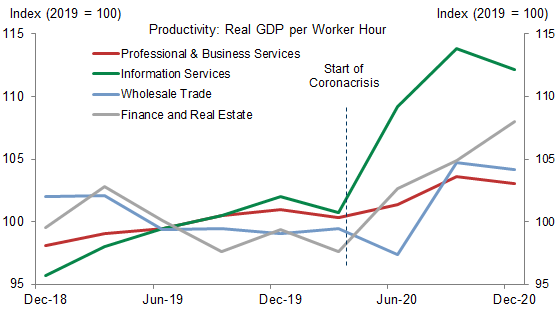

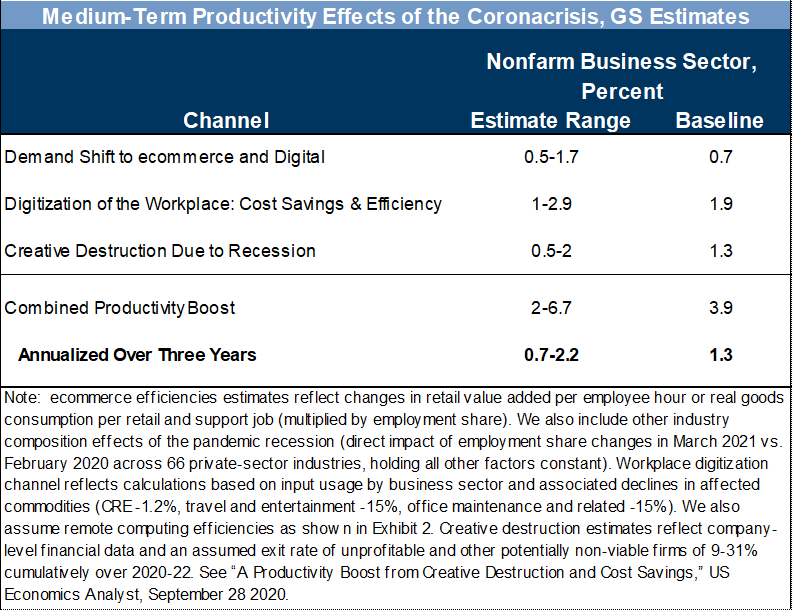

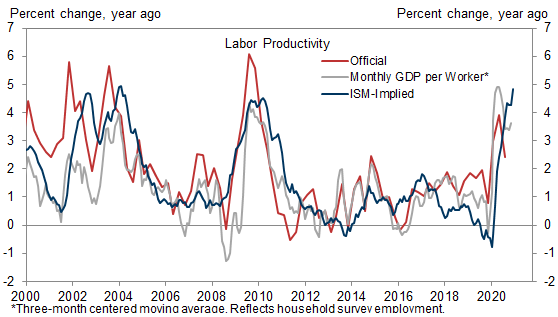

While productivity growth was disappointing during the last cycle—averaging +1¼% annually vs. the long-term average of just over 2%—we forecast much better progress in the early 2020s. Specifically, we expect three drivers of lasting productivity gains in the wake of the pandemic recession: 1) an accelerated demand shift to ecommerce and other higher-productivity segments; 2) the digitization of the workplace (cost- and time-savings from remote computing and virtual meetings); and 3) a boost from creative destruction, with some unprofitable firms shrinking or closing down. We forecast the contribution to productivity growth in the post-pandemic economy from each channel based on survey data and the experience so far during reopening.

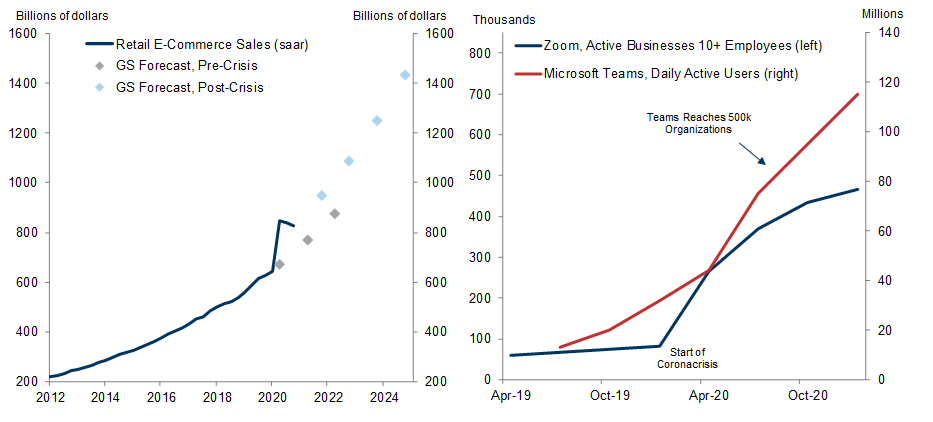

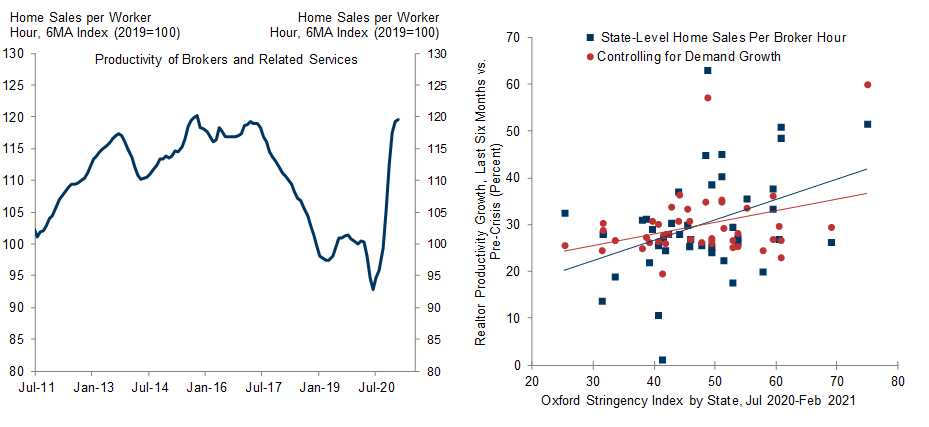

The shifts toward ecommerce, virtual meetings, and Work-from-Home all appear likely to persist to some degree, even with the reopening progressing quickly. Ecommerce share gains have extended into 2021, firms report that they expect three times as many external meetings to be conducted virtually, and Zoom and Teams continue to add users—albeit at a slower pace.

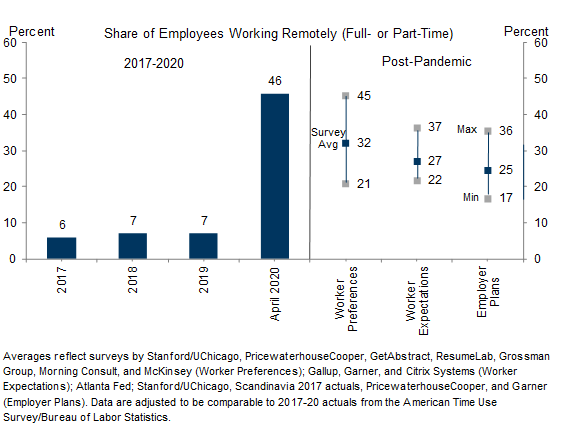

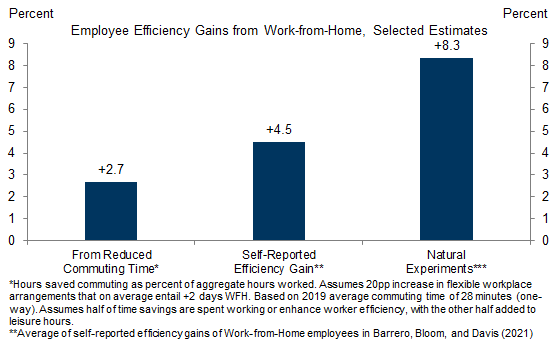

Surveys of both employees and employers indicate that Work-from-Home and flexible workforce arrangements will also remain in place for around a quarter of employees. For the roughly 45% of the workforce for whom it is viable, our review of surveys, natural experiments, and cross-sectional macro data indicates that remote computing probably enhances productivity by 3-8% on average.

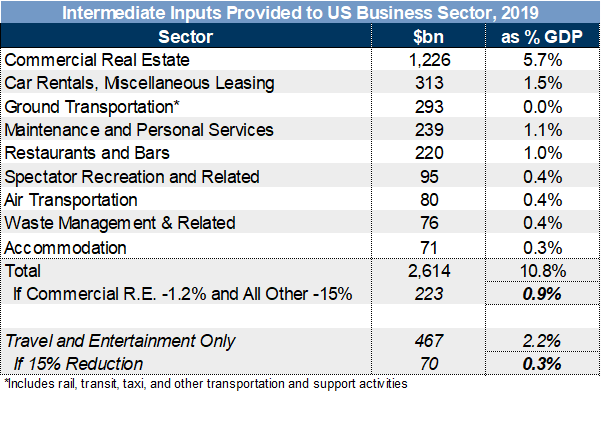

The cleansing aspect of recessions—so called “creative destruction” from the closures of money-losing and low-return businesses—is a final reason to expect above-trend productivity growth, even if the scale of business closure is much smaller than following the financial crisis.

By our estimates, these three channels are likely to boost the level of productivity in the nonfarm business sector by at least 2% cumulatively by 2022 (relative to trend), and potentially by as much as 7%. Our baseline forecast envisions a 4% boost to medium-term productivity levels relative to trend—or a +1.3pp boost to annual productivity growth over 2020-2022. While this estimate is large, our timely proxies for productivity growth indicate cumulative gains relative to the pre-crisis trend already in the 3-4% range.

Productivity in the Post-Pandemic Economy

Work-from-Home in the Post-Pandemic Economy

The Digitization of the Workplace

That Could Have Been an Email: Workforce Efficiencies from Remote Computing

The Productivity Outlook

Spencer Hill

- 1 ^ This gain predated the surge in demand related to the Biden stimulus. A more timely but less precise proxy for productivity in the sector—real goods consumption per employee in retail, warehousing, and delivery—has risen 9.4% since the fourth quarter of 2019.

- 2 ^ For example, the number of businesses with at least 10 employees conducting meetings on Zoom decelerated in the January quarter (+7.7% qoq after +17.2% in the previous quarter). Zoom’s revenue guidance indicates continued growth in the spring quarter and for the full year, despite the continued reopening of the economy.

- 3 ^ Even after the surge in 2020 to accommodate the lockdowns and temporary restrictions in office capacity the majority of CIOs expect to increase spending levels this year. Our analysts note that Work-from-Home “has driven businesses to re-evaluate their networking needs and this result suggests that most are finding more investment is necessary.”

- 4 ^ Several other shifts in consumer and business behavior are also likely transitory—for example, activities still unavailable or restricted due to public health risks.

- 5 ^ The authors speculate that Work-from-Home shares may “increase permanently as workers and employers become more comfortable with telework arrangements.”

- 6 ^ Albeit with a wider range of opinion: 17% to 36% on this basis. Generally speaking, executives appear more cautious than employees about the long-term viability of remote-computing, with an Enaible study finding that 84% are concerned whether staff can be effectivity managed remotely and 76% are concerned about worker productivity and their ability to monitor it. The jury is still out in many cases: A McKinsey study found that only 32% of employers have clearly communicated their post-pandemic plans on this dimension to workers, and 40% have made no communications whatsoever.

- 7 ^ Additionally, a PricewaterhouseCoopers study found that while 87% of firms plan to make changes to their real estate strategy, downsizing was not a particularly common result. In fact, 56% expect more space will be needed—for example to improve the office experience.

- 8 ^ Surveys provide less guidance on the medium-term impact on professional development, which could be significant particularly for younger employees and 100%-remote workers. This in turn argues in favor of the hybrid (flexible workplace) model.

- 9 ^ Residential brokers, agents, appraisers, and office staff.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.