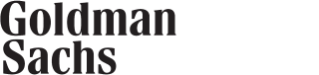

Fed officials are still in the early stages of researching a potential central bank digital currency (CBDC), but other central banks are further along in the process. We provide a status report on CBDCs around the world, focusing on the reasons that foreign central banks are considering a CBDC, their design choices, and their approaches to managing the risks that a CBDC could pose.

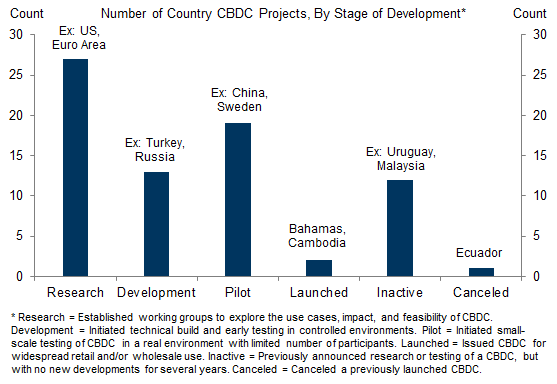

Central banks cite several reasons for considering a CBDC. Emerging economy central banks emphasize increasing financial inclusion and payments efficiency. Advanced economy central banks, including the Fed, instead emphasize increasing the robustness of the payments system, though most consider it an open question whether a CBDC would accomplish this. Many central banks also appear concerned about potential competition from cryptocurrencies or stablecoins.

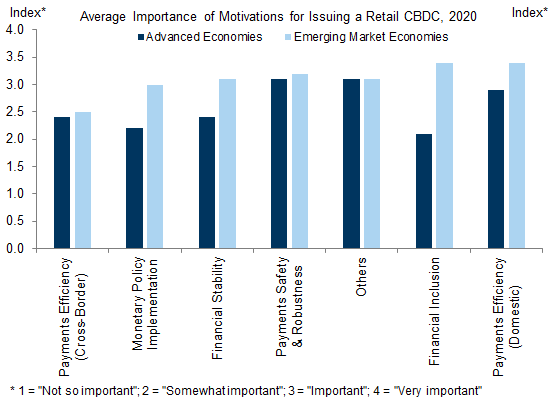

Early CBDCs take a range of forms, but many share common features. Central banks have tended to choose or are exploring designs that feature both tokens and accounts, are intermediated by commercial banks, use distributed ledger technology or both that and centralized clearing, do not pay interest, and permit at least small-scale offline transactions.

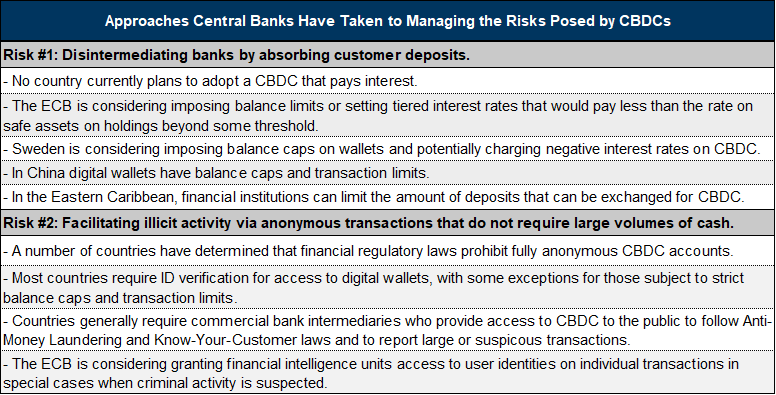

Central banks have been cautious to avoid two key risks that CBDCs could pose. To avoid disintermediating banks by depriving them of their deposit base, central banks have imposed caps on balances, paid no interest on CBDC, or considered imposing a penalty interest rate on holdings above some threshold. To avoid facilitating illicit activity, central banks have mostly decided against fully anonymous accounts or capped anonymous transactions, and have tasked commercial bank intermediaries with monitoring customers and transactions.

A Status Report on Central Bank Digital Currencies Around the World

Tokens vs. accounts. So far countries have either introduced token-based CBDCs or approaches with both tokens and accounts. In practice the distinction is sometimes blurry—the Swedish pilot, for example, is token-based, but offers users the option to have trusted banks store their tokens and conduct their exchanges in order to provide security against accidental loss of their tokens. This appears account-based, but the accounts transact tokens via a distributed ledger.

Direct vs. intermediated accounts. Most countries have chosen approaches intermediated by commercial banks rather than offering the public direct accounts at the central bank.

Clearing mechanism. More central banks are considering using a distributed ledger technology than traditional centralized clearing. However, all central banks using a distributed ledger are using a permissioned version that allows them to choose who can participate in the ledger rather than a permissionless approach open to the public like Bitcoin.

Payment of interest. Several central banks have decided that their CBDC will not pay interest. Some are exploring tiered interest schemes that would pay a normal interest rate on a modest amount of CBDC and a lower rate on additional CBDC, in order to discourage large deposits.

Offline transactions. Many CBDCs permit at least some offline transactions.

David Mericle

Laura Nicolae

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.