The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) capped state and local tax (SALT) deductions against federal income taxes, effectively raising state and local (S&L) taxes and increasing incentives for high-income households to relocate to low-tax states. More recently, two proposed policy changes—a lifting of the cap on SALT deductions, and state income tax increases on high earners—have revived questions about whether S&L tax increases induce migration from high- to low-tax states, and how such moves might affect S&L budgets.

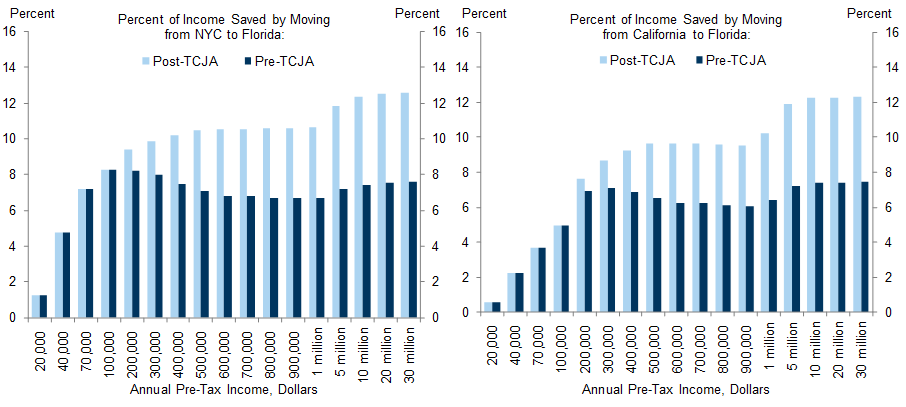

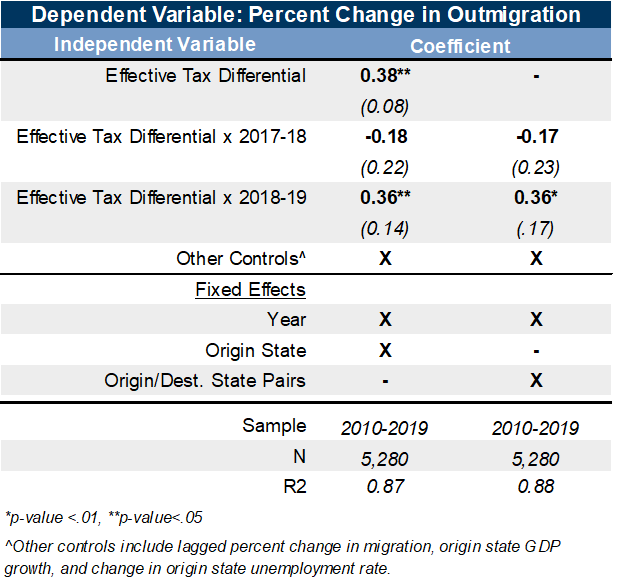

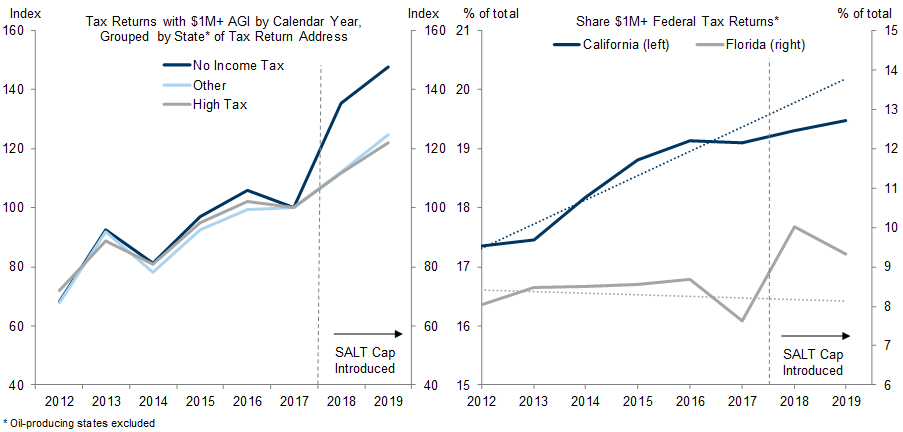

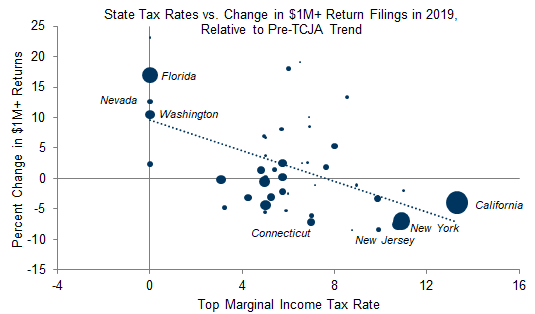

The incentives to migrate for tax reasons can be quite large—for example, the TCJA’s cap on S&L tax deductions effectively raised total taxes on top earners in California and New York by over 4pp, to as much as 12pp more than they would pay in states without income taxes. Consistent with prior academic studies, we find small increases in population outflows from high-tax to low-tax states after the SALT deduction cap went into effect.

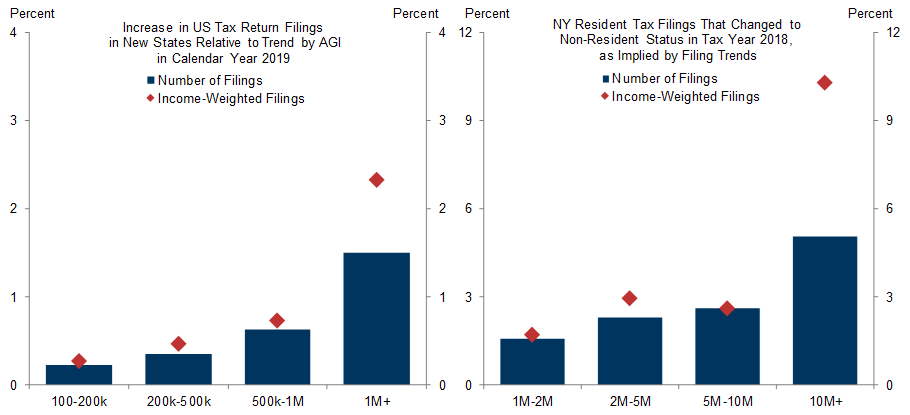

Of course, tax-based migration incentives were largest for high-earning households, and IRS tax filings by income levels suggest that around 1.5% of households earning over $1M moved to low-tax states after the SALT deduction cap was introduced, relative to the prior trend. Furthermore, trends in New York resident and non-resident tax filings suggest that over 5% of households earning over $10M per year left the state due to the SALT deduction cap.

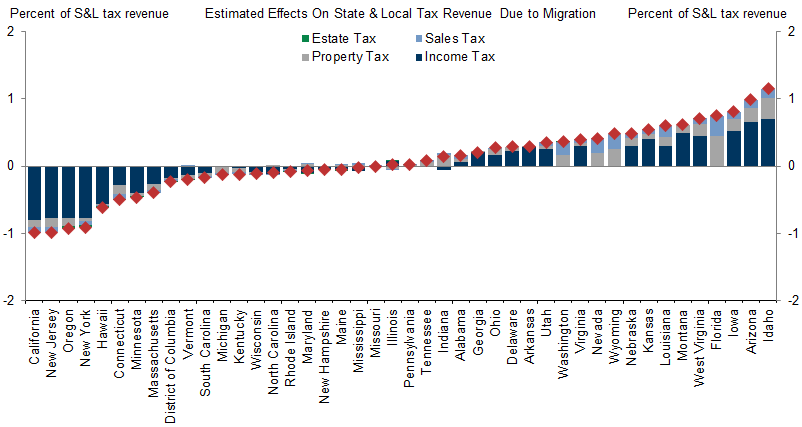

We estimate that the SALT deduction cap lowered tax revenues in high-tax states by up to 1% due to tax revenue declines from emigration. Although revenue increases in lower-tax states that experienced more in-migration partially offset these declines, we estimate that aggregate S&L tax revenues declined by just under 0.5% due to the SALT deduction cap.

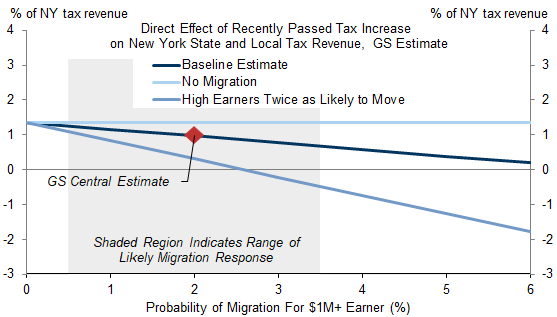

Looking ahead, our baseline assumption is that Congress will raise the cap on SALT deductions to $50k, which should slow but not reverse the recent tax-driven migration. However, tax hikes on high-income households like the one that recently passed in New York will likely increase emigration from high-tax areas. After modeling the New York tax change, we estimate that the loss from emigration will offset about 30% of the revenue increase from higher taxes, although the post-pandemic uncertainty is large and skewed to the higher side.

No Taxation Without Emigration

Benchmarking Emigration Incentives and Responses

The SALT Deduction Cap and Interstate Migration

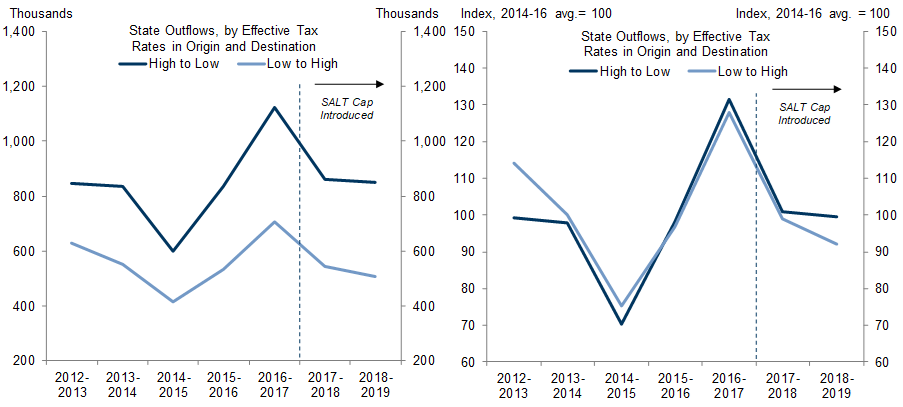

Exhibit 3: Households Were Already Migrating From High- to Low-Tax States Before SALT Deductions Were Introduced, But Net Outflows May Have Accelerated Slightly in 2018-2019

SALT Deduction Caps and Emigration of High Earners

The Impact of SALT Deduction Caps on State and Local Budgets

Income Tax – We use our estimates of income-weighted net migration by income group and state and apply the appropriate tax rate for each state and income group to estimate the change in income tax revenue.

Property Tax – We first use the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to calculate the average primary residence value by income level, and apply the effective property tax rate for the largest city in each state to estimate annual property tax payments per household. We then multiply by our net migration estimates by state and income levels to estimate the change in property tax revenue.

Sales Tax – We first use the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) to calculate the share of income spent on taxable items. We then apply the general sales tax rate for the largest city in each state to estimate the annual sales tax payments per household, and multiply by our net migration estimates by state and income levels to estimate the change in sales tax revenue.

Estate Tax – For the 13 states with estate taxes, we first use the SCF and state tax laws to calculate the incidence of estate taxes by income group. We then use our net migration estimates for each state and income level to calculate the implied decline in estate tax revenue, and rescale by average estate tax revenue in recent years.

How Much Will Emigration Offset the Revenue From New York’s Recent Tax Increase?

Joseph Briggs

- 1 ^ Tax incentives for households with incomes below this level were unchanged because most households take the standard deduction.

- 2 ^ Struyven, Daan, “Losing My Deduction”, US Economic Analyst, November 24, 2017

- 3 ^ Coven, Joshua, Arpit Gupta, and Iris Yao. "Urban flight seeded the covid-19 pandemic across the United States." Available at SSRN 3711737 (2020).

- 4 ^ Spencer Hill, “The Work-from-Home Windfall: A Productivity Update”, US Daily, December 23, 2020

- 5 ^ We restrict analysis to the top 12 destination states for each origin state to exclude state-pairs for which little interstate migration occurs. Our results are robust to alternative thresholds.

- 6 ^ In our analysis we exclude oil-producing states like Texas, Alaska, South Dakota, and North Dakota because the number of $1M+ tax returns is largely determined by transitory oil price shocks, making it difficult to find an adequate control group to test for deviations from trend. Omitting these states likely yields conservative estimates of tax-induced migration, however, since most oil-producing states have low or no income taxes.

- 7 ^ Moreover, results are again larger on an income-weighted basis for households in the top income group, which suggests a very strong migration response for the highest-earning households.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.