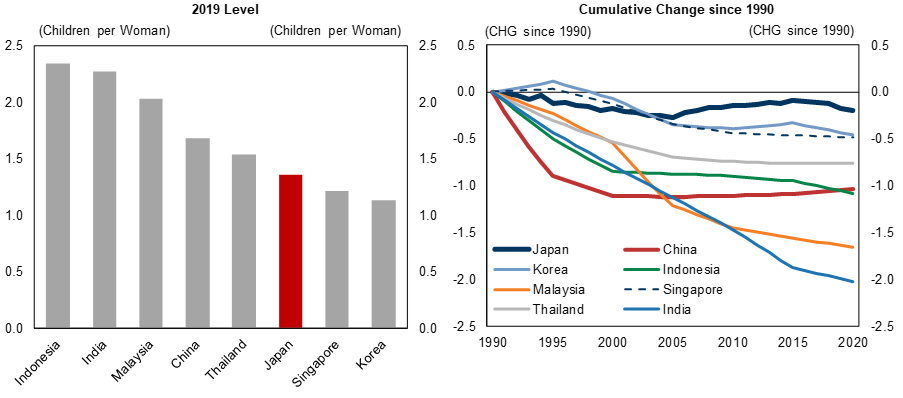

Japanification was initially triggered by worsening demographics. However, thanks partly to a steep increase in the female participation rate, Japan's GDP has decoupled from the steadily declining working-age population. Given that many other Asian countries have begun to face demographic headwinds, we draw possible lessons for these countries from the successes to date and challenges ahead of "Womenomics" in Japan.

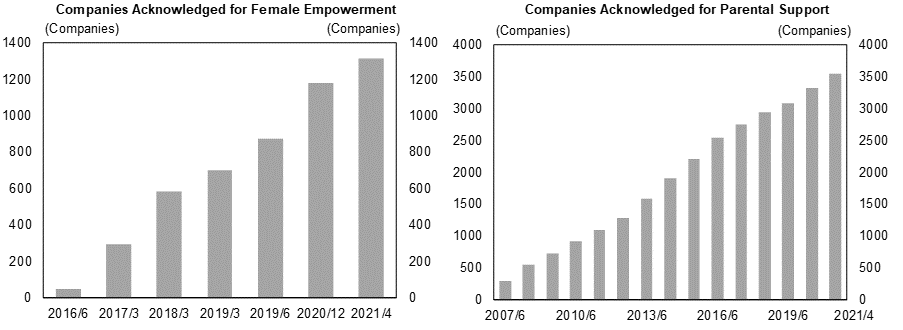

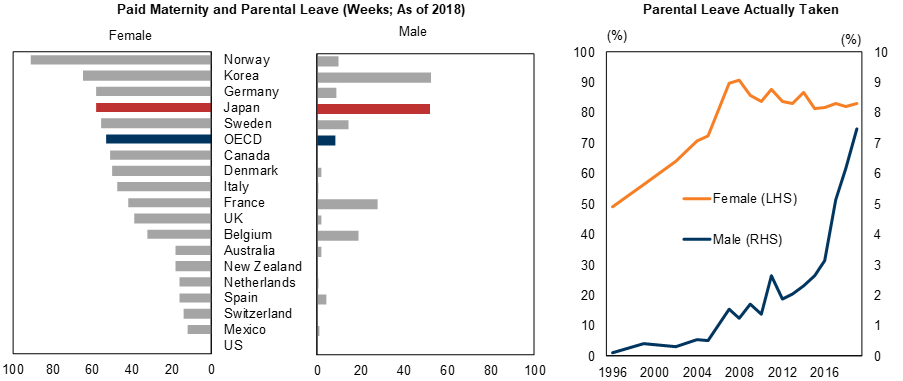

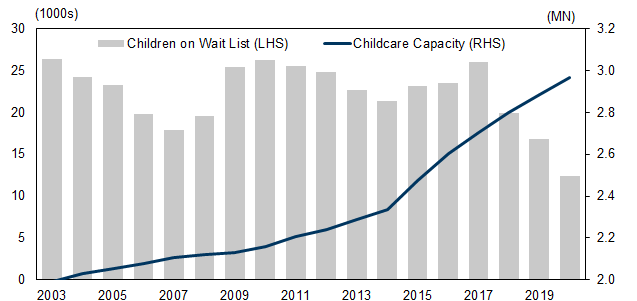

The core Womenomics strategies implemented in recent years include: (1) incentivize companies to promote women’s participation in the workplace particularly by requiring disclosure of gender diversity-related information, (2) improve the parental leave system and increase uptake rates, (3) expand childcare capacity, and (4) implement work-style reforms that limit overtime hours and mandate equal pay for equal work.

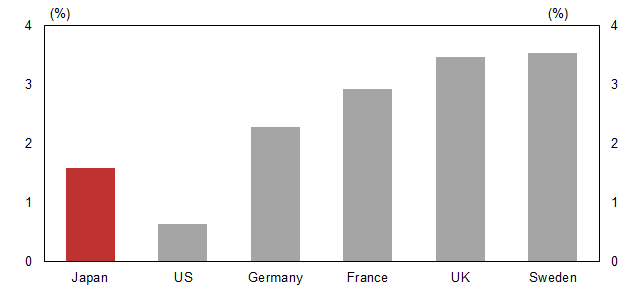

Strategies (1) to (3) above have already started having a tangible effect, in our view. In particular, we highlight that Japan’s parental leave system is now among the most generous in the world and more parents are using it. By contrast, more time will be needed to assess the effectiveness of the work-style reforms in strategy (4), given that these reforms are still in their infancy.

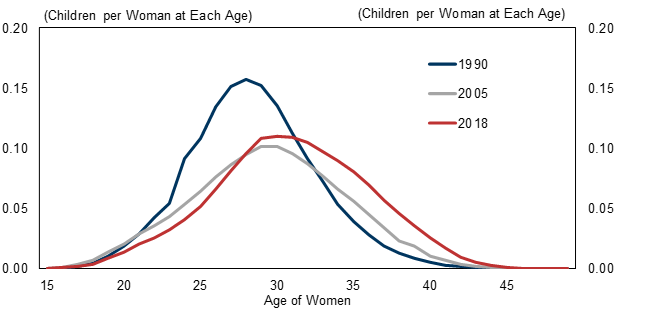

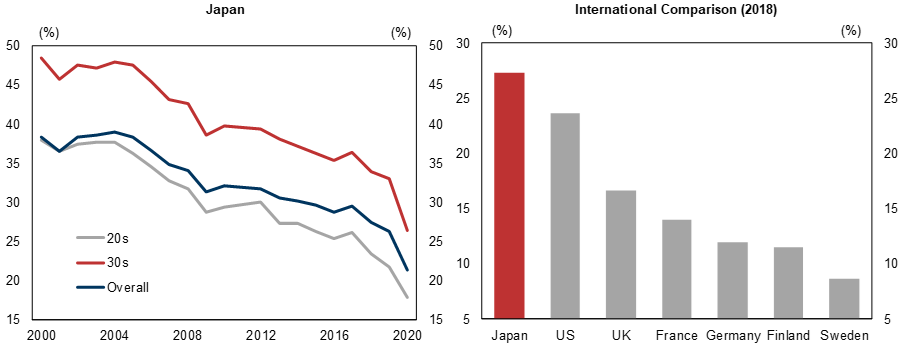

Heightened awareness among businesses, enhancement of parental leave systems, and expansion of childcare facilities have also likely increased incentives for working women to have two or more children, and this is likely to be contributing to the rise in the fertility rate among Japanese women in their 30s.

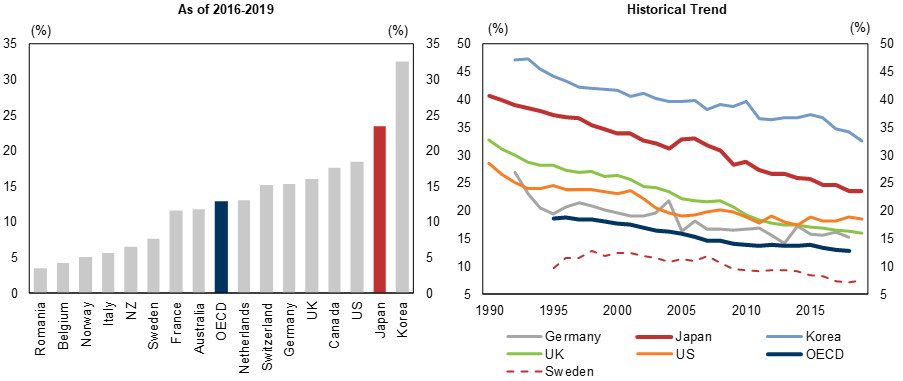

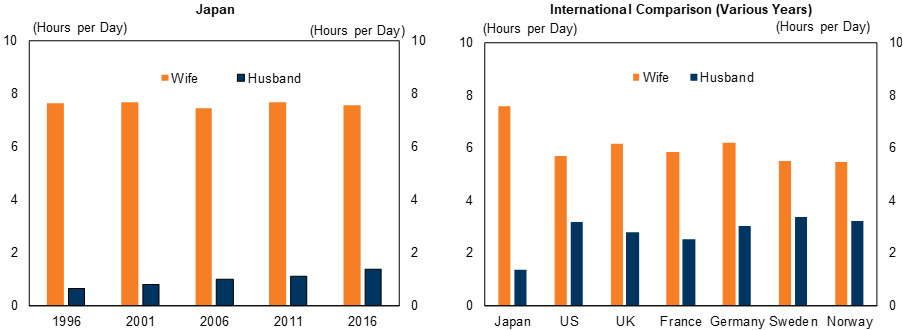

However, we think that there remain significant challenges to be addressed to improve the future female labor environment in Japan, which include: (1) the gender pay gap stemming from a much higher non-regular worker ratio in the female workforce, (2) men’s willingness to participate in housework/child-rearing, and (3) more general fiscal support for family assistance. Regarding (3), the former Abe administration decided to earmark some of the increased tax revenue from the October 2019 consumption tax hike for making pre-school education free. We view this positively as a manifestation of the government’s sense of urgency, but see continued, long-term efforts as essential.

What Japan's Womenomics Tells Us About Demographic Strategy in Asian Nations

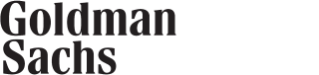

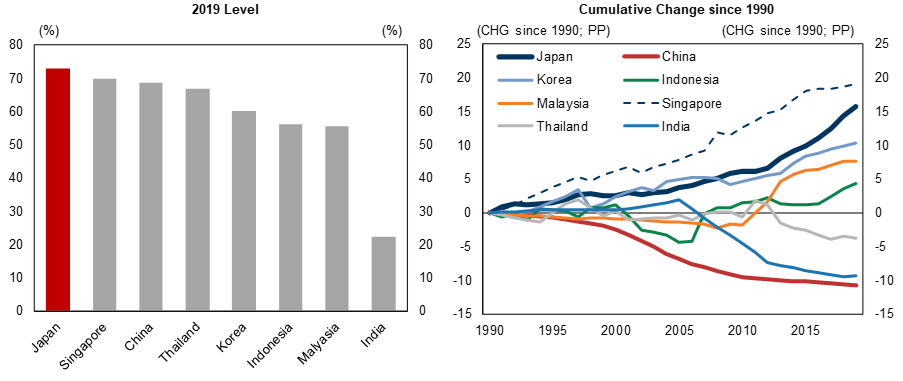

Demographic Headwinds Overshadowing Asian Nations

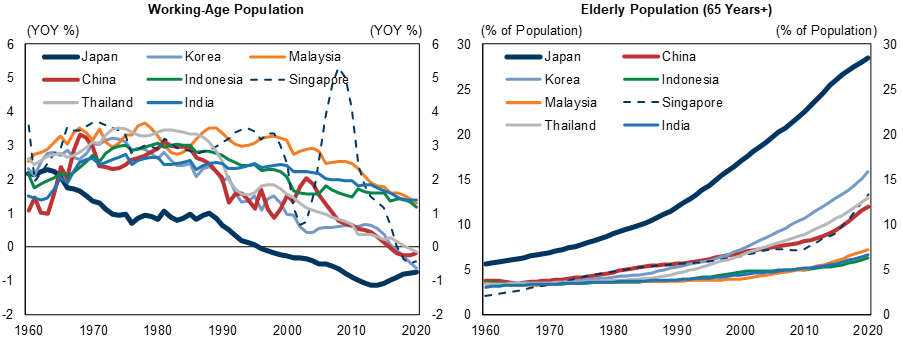

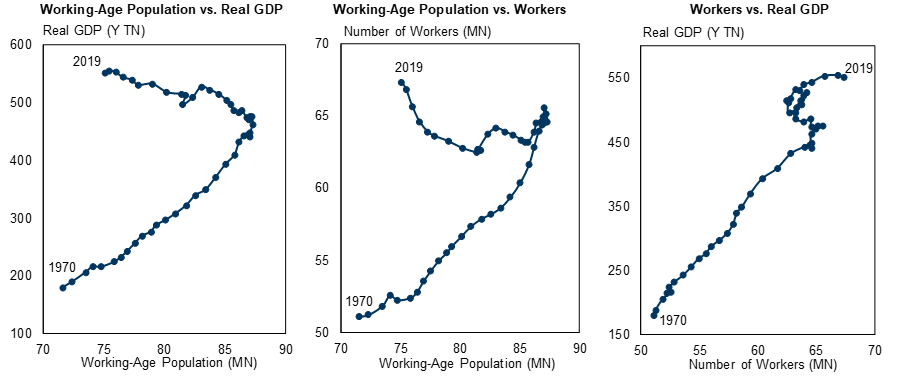

Japan's GDP Decouples from the Secular Downtrend in the Working-Age Population

Japan's Female Participation Rate Has Increased Substantially, Even Compared with Other Asian Nations

Unpacking the Successes and Challenges of Japan’s Womenomics

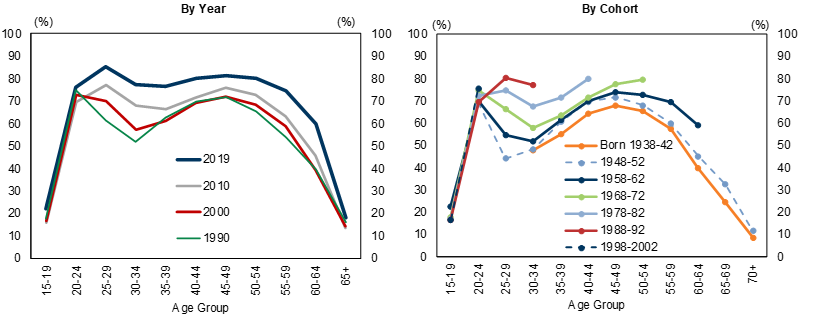

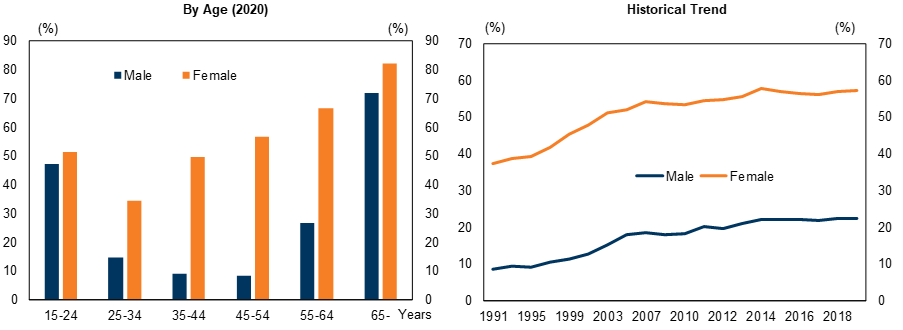

Success to Date: The M-Curve Has Improved Considerably

Challenges Ahead: Gender Pay Gap, Male Participation in Child-Rearing, Government Family Assistance

Exhibit 14: Long Working Hours Are Being Reduced Rapidly for Men, but There Is Still Room for Improvement

Recent Publications

Japan Economic Analyst

Jun 1, 2021 | |

Apr 28, 2021 | |

Apr 14, 2021 | |

Mar 31, 2021 | |

Mar 26, 2021 | |

YCC Credibility Through the Lens of UST-JGB Yield Sensitivity | Mar 9, 2021 |

Mar 2, 2021 | |

Feb 25, 2021 | |

Feb 19, 2021 | |

Jan 27, 2021 | |

Updated Outlook for the Japanese Economy with Renewed State of Emergency | Jan 7, 2021 |

Dec 10, 2020 | |

Nov 26, 2020 | |

Suganomics and SME Reforms: The Challenge of Enhancing Productivity | Nov 12, 2020 |

Nov 9, 2020 | |

Oct 15, 2020 | |

Oct 2, 2020 | |

Reliance on China to Meet "Remote Working" Demand Likely to Persist Post COVID-19 | Sep 18, 2020 |

Sep 16, 2020 | |

Aug 27, 2020 | |

Higher value-added supporting exports and reducing vulnerability to JPY appreciation | Aug 18, 2020 |

Aug 7, 2020 | |

Jul 28, 2020 | |

Sharp Decline in USD Hedge Cost Would Provide Impetus for US Bond Investment | Jul 17, 2020 |

Jul 10, 2020 |

Japan Views / Japan Economic Flash

- 1 ^ See Naohiko Baba, "Lessons from Japan's Demographics: Delayed Recognition, Delayed Action," Japan Economics Analyst, June 28, 2019.

- 2 ^ See Sharon Bell, "European Equities and Japanification," Global Strategy Paper, July 1, 2019.

- 3 ^ See Maggie Wei, "The Implications of China's Shrinking Working-Age Population," Asia Economics Analyst, May 25, 2021.

- 4 ^ See Naohiko Baba, "Managing Japanification: What Japan's Experiece Tells Us," Japan Economics Analyst, Janaury 27, 2021.

- 5 ^ See Andrew Boak, BIll Zu, and William Nixon, "Womenomics in Australia - Some Progress, but More Potential," Australia and New Zealand Economics Analyst, November 29, 2019.

- 6 ^ See Kathy Matsui, Hiromi Suzuki, and Kazunori Tatebe, "Womanomics 5.0: 20 Years On," Japan Portfolio Strategy, April 16, 2019.

- 7 ^ See Hiromi Suzuki and Kazunori Tatebe, "2021 AGMs: Corporte Governance Focus Points," Japan Corporate Governance Monitor, June 19, 2021.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.