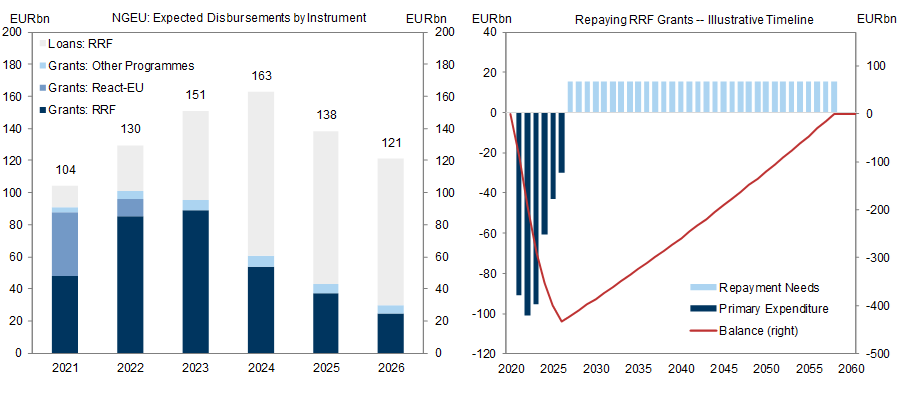

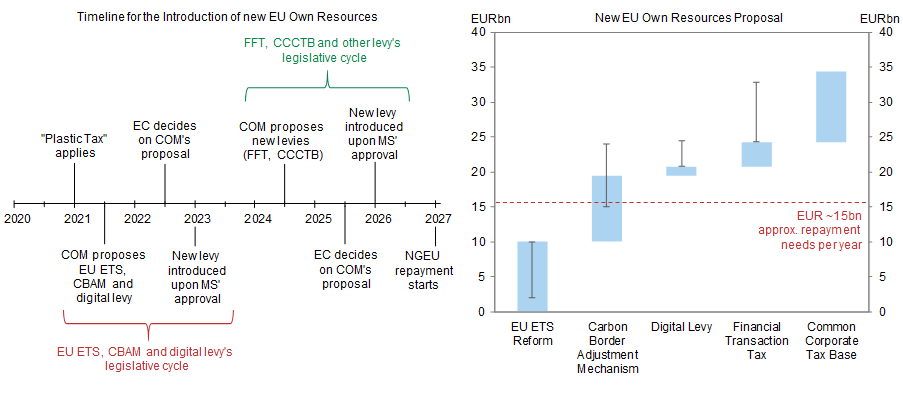

The Recovery Fund—which will start disbursements to member states soon—was agreed as a one-off package to support the recovery from the covid crisis. Following the disbursement of grants over the next five years, repayment is planned for 2027-58, through a combination of member state contributions and new EU-wide revenue sources.

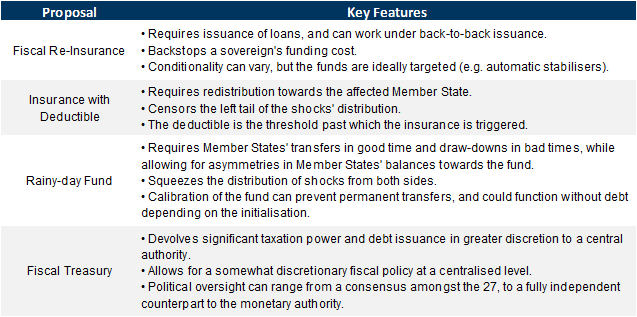

A number of commentators, however, have argued that the Recovery Fund is more than a one-off tool and provides a breakthrough in financial integration. Visions for the Recovery Fund range from a permanent loan facility, to a “rainy day" fund, to a central fiscal authority with tax and spending powers.

Given the political difficulty of agreeing on a large, central fiscal capacity, we expect the Recovery Fund to advance European fiscal integration more incrementally but along a number of important dimensions. We see a low bar for a continuation of the Recovery Fund loan facility, expect the new EU-wide revenue sources to allow for a permanently larger EU budget and, most importantly, regard the Recovery Fund as a precedent for a Europe-wide fiscal tool that can be utilised again during a future crisis.

In sum, the Recovery Fund is unlikely to be either temporary or Hamiltonian, but an important step down the road of European integration.

The Recovery Fund—Transitory Tool or Hamiltonian Moment?

The Plan

The Vision

The Reality

- 1 ^ See Council Decision 10046/20.

- 2 ^ We use an average of Bund and OAT 15y forward rates from 2021 to 2027.

- 3 ^ See Schwarcz (2021) for an overview of the Commission’s proposals.

- 4 ^ See Vandenbroucke and co-authors (2020).

- 5 ^ For a short discussion, see Gros (2014).

- 6 ^ As for instance, in Lenarčič and Korhonen (2018).

- 7 ^ Alexander Hamilton was the first Secretary of the US Treasury and is widely recognised as having spearheaded the mutualisation of the 13 American colonies’ debts during the War of Independence while carving out designated sources of revenues.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.