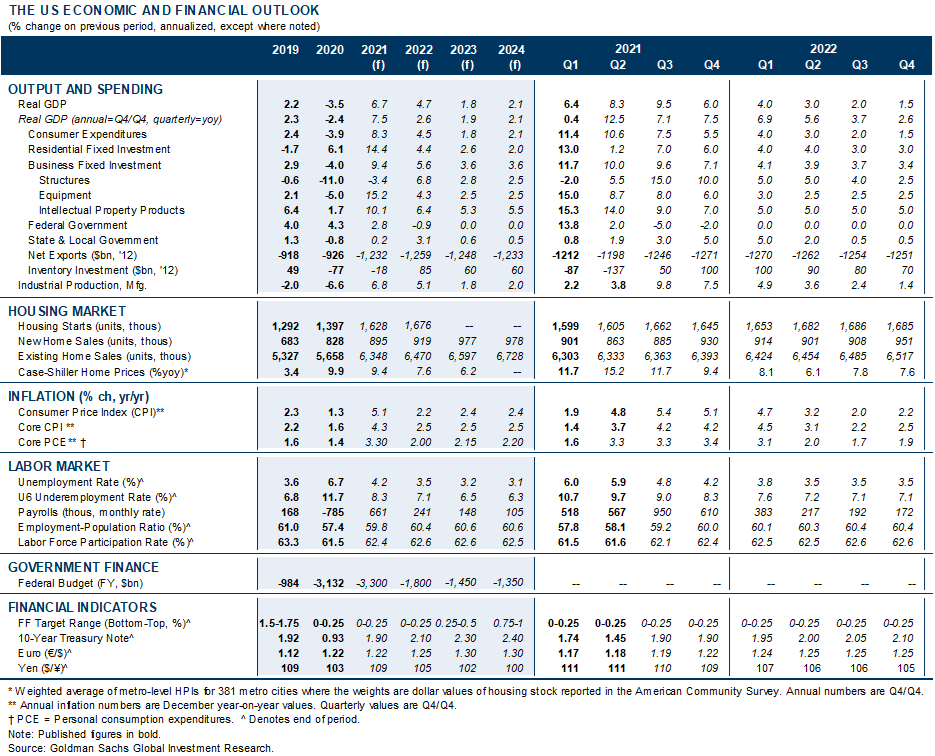

On July 9, President Biden issued an executive order on promoting competition in the US economy. In this week’s Analyst, we survey the current competitive landscape and how it might change in response to President Biden’s proposals.

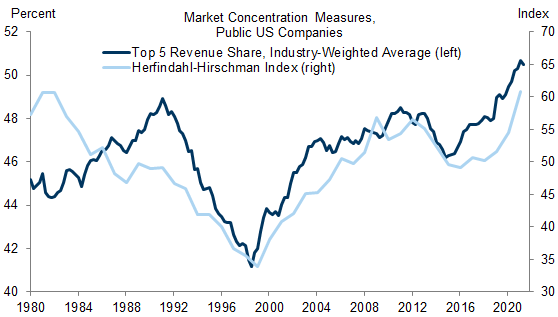

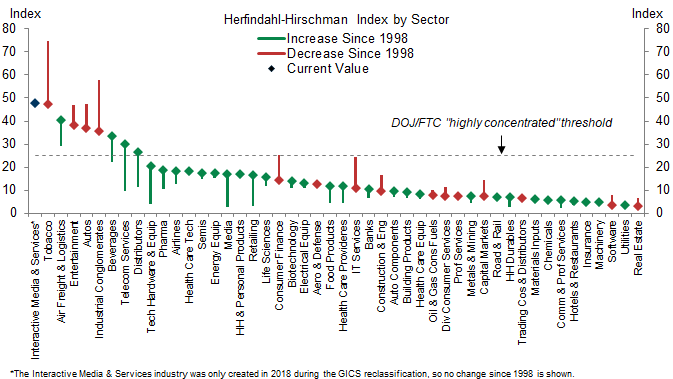

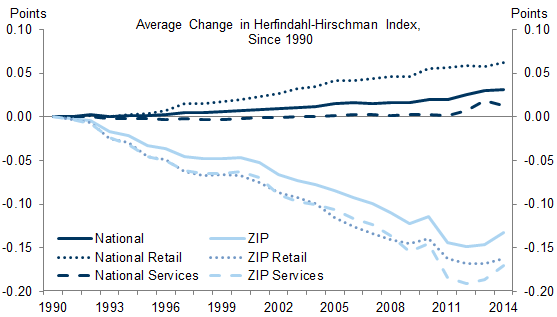

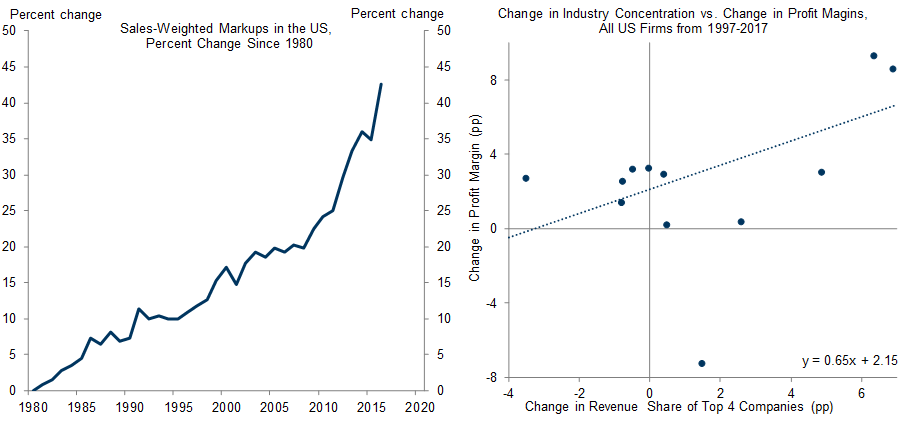

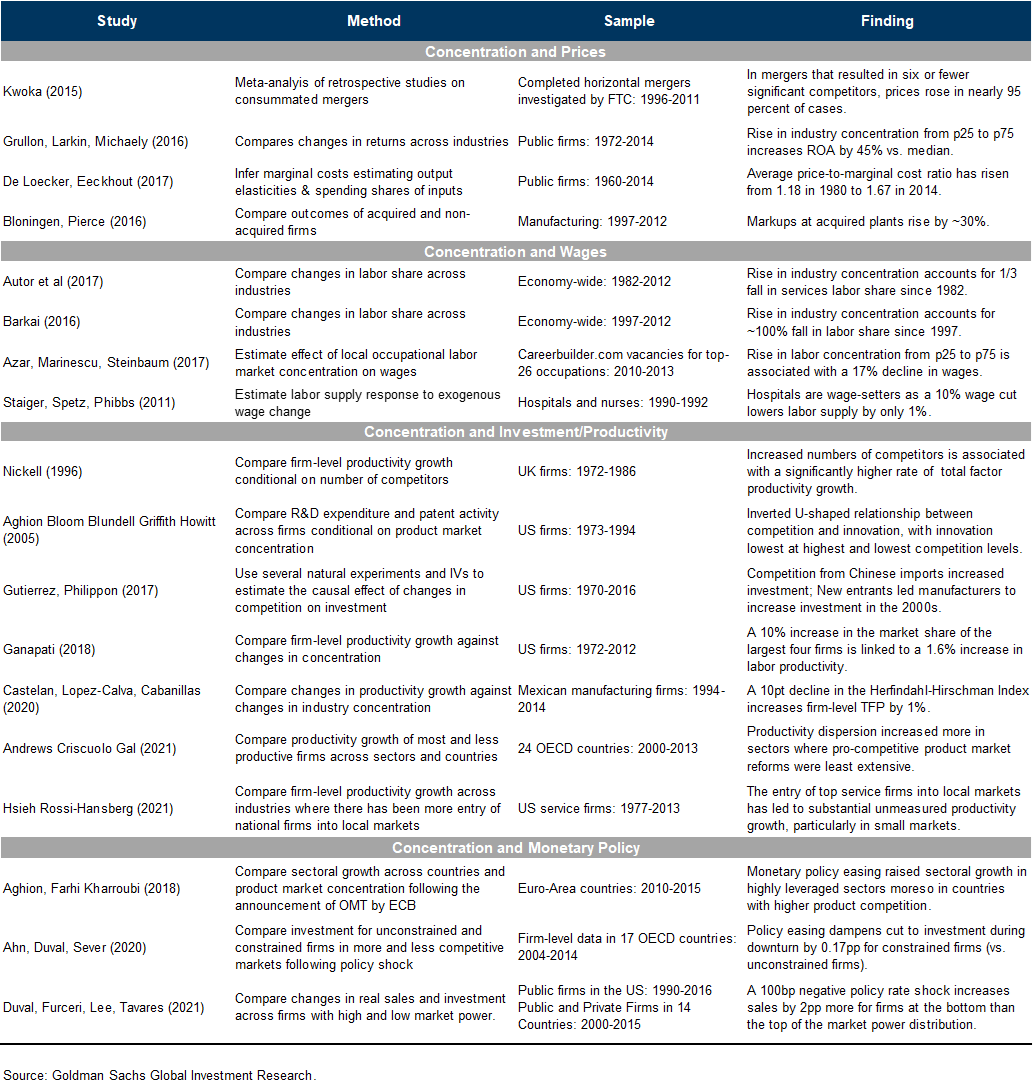

The Biden administration’s competition agenda is motivated by a long-run rise in market concentration, which is partially explained by the increased prevalence of platform markets that benefit from positive network effects. The rise in national concentration may not have reduced consumer welfare, however, since concentration has actually declined at the local level.

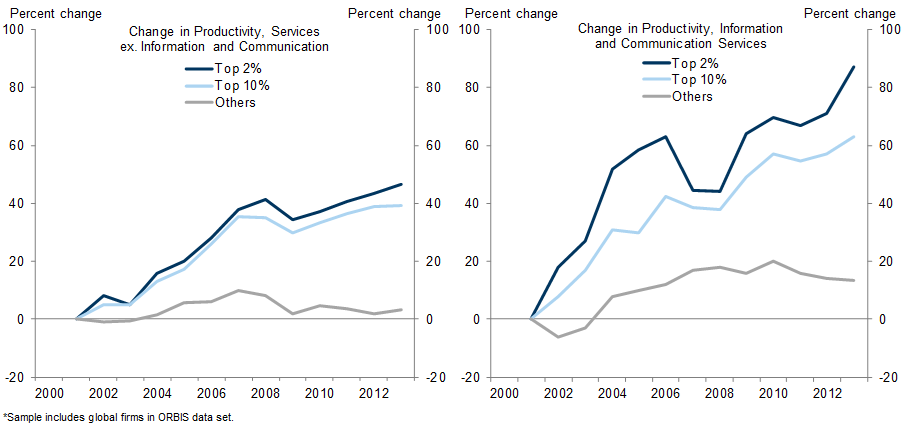

Whether the rise in national concentration is problematic depends on its underlying cause, since it could reflect less active competition policy that benefits large firms and ultimately lowers output, but could also reflect increased productivity dispersion and the rise of superstar firms that have boosted growth. We see evidence that both of these explanations—which reinforce one another—have contributed to the long-run concentration increase.

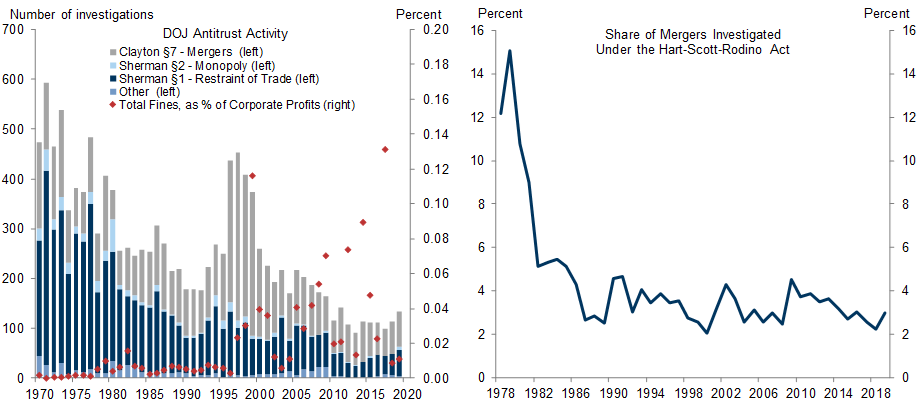

We see three potential antitrust policy changes that could push against rising concentration. First, antitrust policy will likely broaden its focus to consider the interests of producers, suppliers, and workers, not just consumers. Second, antitrust policy will likely increasingly emphasize competition for its own sake rather than economic outcomes. Third, we anticipate a lower bar to challenging business combinations and practices and more active antitrust enforcement.

In terms of implementation, new leadership at antitrust agencies will likely meaningfully change enforcement, and the FTC has already signaled intent to modify merger guidelines. We also see the July 9 executive order—which has many industry-specific recommendations but few specific actions—as signaling a renewed executive branch focus on antitrust issues. However, legislative actions will likely be more incremental, and it is unclear whether bills proposing changes to the regulation of online platforms have enough support to pass.

Academic studies suggest that an antitrust policy shift that pushes against rising market concentration will lower prices and increase the labor share of GDP. The implications for productivity growth are ambiguous, however, with several recent studies finding a positive relationship between concentration and productivity.

Concentration, Competition, and the Antitrust Policy Outlook

The Current Competitive Landscape

Concentration vs. Competition

The Competition Policy Outlook

A broader focus than “consumer welfare”. The July 9 White House executive order focuses on the interests of producers, suppliers, and workers, not just consumers. A number of congressional Democrats share the position, which is a basic tenet of the “New Brandeis School” of antitrust thinking.

A greater focus on “structures and processes” rather than economic outcomes. Since the 1980s, antitrust enforcement has focused primarily on price effects, often using quantitative empirical analysis. However, a focus beyond consumer welfare makes consumer price effects less central. Moreover, in an era of free digital services, measuring competition on price alone becomes more difficult.

A lower bar to challenging business combinations and practices and a more active antitrust enforcement. Beyond the approach enforcement takes, there is likely to be more of it. A broader scope, heightened focus and greater resources are likely to raise the probability that antitrust agencies investigate a given practice or business.

The intersection of intellectual property and antitrust law: The order targets patent evergreening strategies, pay-for-delay settlements, and the licensing of standard-essential patents. These are of primary importance to biopharma and the tech/telecom sector, but could have implications for other sectors as well.

Regulatory and licensing requirements: The order raises the issue only in general but reforms could potentially lower the bar for new entrants in a number of industries, among them real estate, health care, and agriculture. Licensing requirements reduce labor market competition by limiting the number of eligible workers.

Non-compete clauses: The focus appears to be on lower-skill workers, in particular, though this could affect a broad range of occupations and industries.

How Will Changes to Competition Policy Affect the Economy?

- 1 ^ Changes over time in the tendency for firms to be publicly listed can create some bias in concentration ratios.

- 2 ^ Esteban Rossi-Hansberg & Pierre-Daniel Sarte & Nicholas Trachter (2020). "Diverging Trends in National and Local Concentration," NBER Chapters, in: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2020, volume 35, pages 115-150, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- 3 ^ Amiti, Mary, and Sebastian Heise. "US Market Concentration and Import Competition." (2021).

- 4 ^ Gutiérrez, Germán, and Thomas Philippon. “Declining Competition and Investment in the US.” No. w23583. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017.

- 5 ^ Diez, Federic, Daniel Leigh and Suchanan Tambunlertchai. “Global market power and its macroeconomic implications.” International Monetary Fund, 2018

- 6 ^ Daan Struyven. “Super Profits and Superstar Firms”. US Economics Analyst, July 22, 2017.

- 7 ^ Andrews, Dan, Chiara Criscuolo, and Peter N. Gal. "The best versus the rest: the global productivity slowdown, divergence across firms and the role of public policy." (2016).

- 8 ^ Daan Struyven. “Superstar Firms, Super Profits, and Shrinking Wage Shares”. US Economics Analyst, February 4, 2018

- 9 ^ Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. “The industrial revolution in services.” No. w25968. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.