We have recently argued that the delta variant poses a manageable risk to the reopening and our constructive view on the European recovery. With continued investor focus on the pandemic developments in Europe, we stress-test our view in Q&A format.

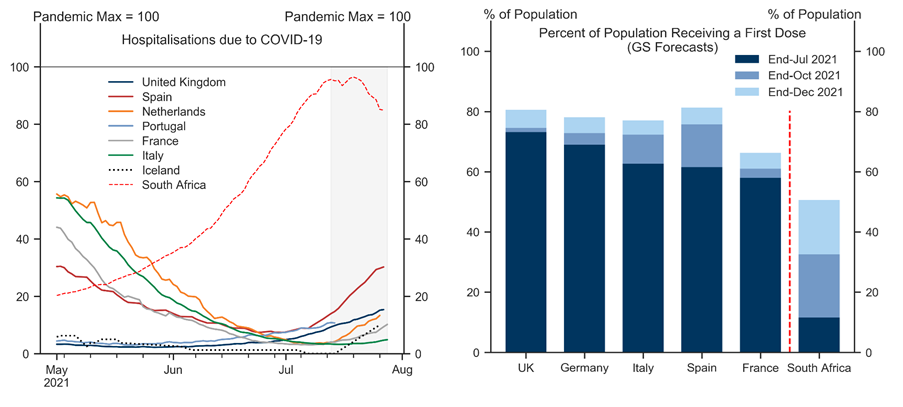

First, it looks like new case growth has peaked for now in the countries exposed early to the delta variant (including the UK and Spain), but will continue to rise elsewhere (including Germany and Italy). Second, our analysis confirms that vaccinations have been a key factor that has kept hospitalisations low. Third, while we find some effects from high infections on consumer behaviour, we see limited evidence so far of a persistent contribution to labour shortages. Finally, we continue to expect a gradual relaxation of remaining restrictions over coming months across Europe in view of manageable delta variant risks.

A Q&A on Delta Variant Risks

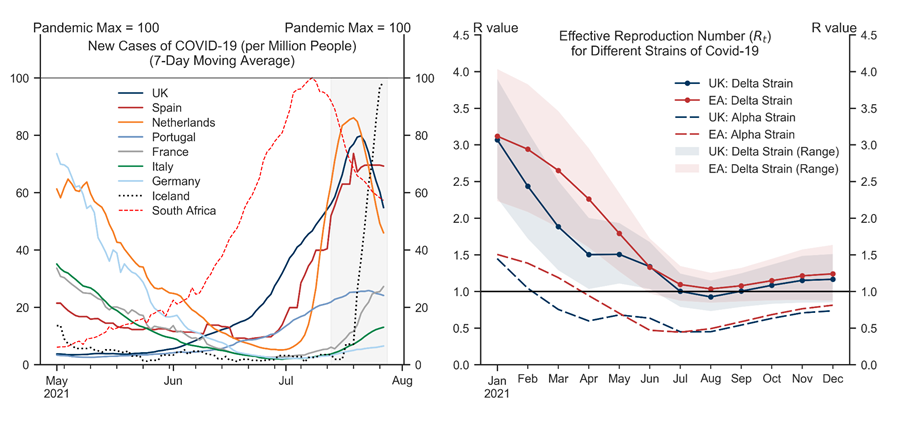

Q1. Have new cases peaked?

Exhibit 1: Early Signs of the Delta Wave Peaking in Some Countries, Pointing to an R Below 1

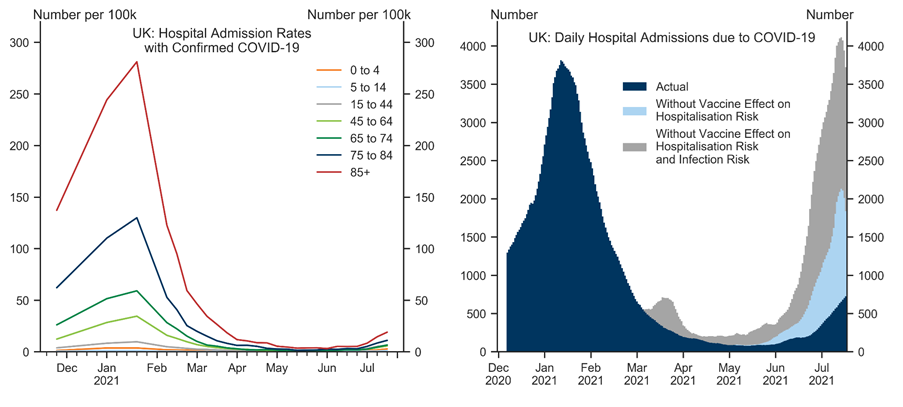

Q2. Has mass vaccination been a key factor in keeping hospitalisations relatively low in Europe?

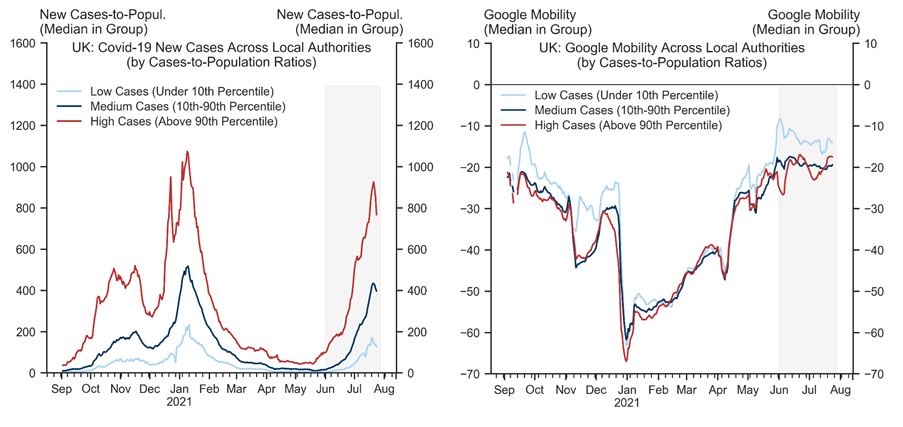

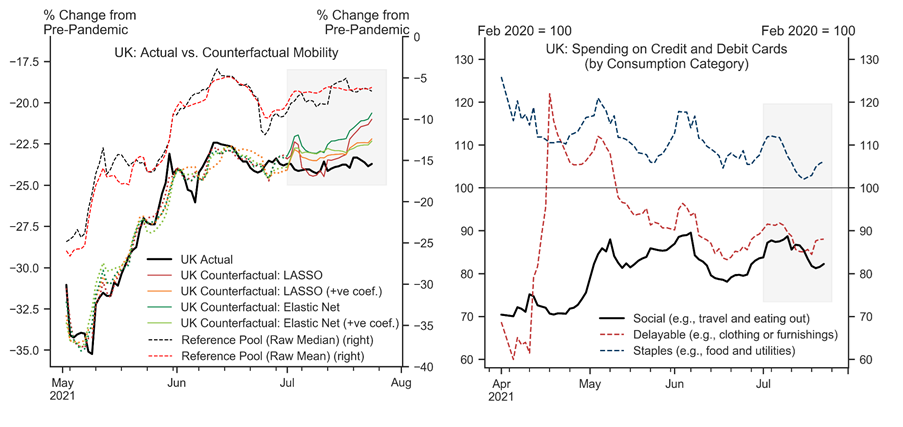

Q3. Has there been a behavioural response from consumers to rising delta-variant cases?

Exhibit 4: Some Drag on Mobility from Very High Cases

Exhibit 5: Recent Slowing in UK Momentum Somewhat Larger Than Elsewhere, But Behavioural Effects Not Visible Across Spending Types

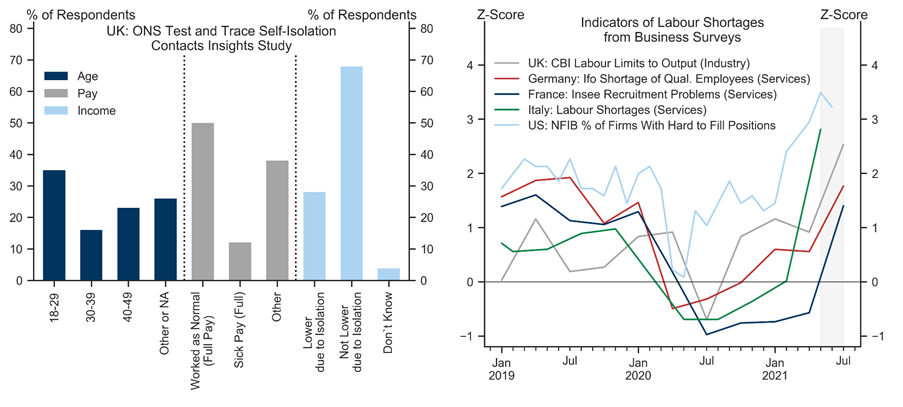

Q4. Has the spread of the delta variant contributed to labour shortages?

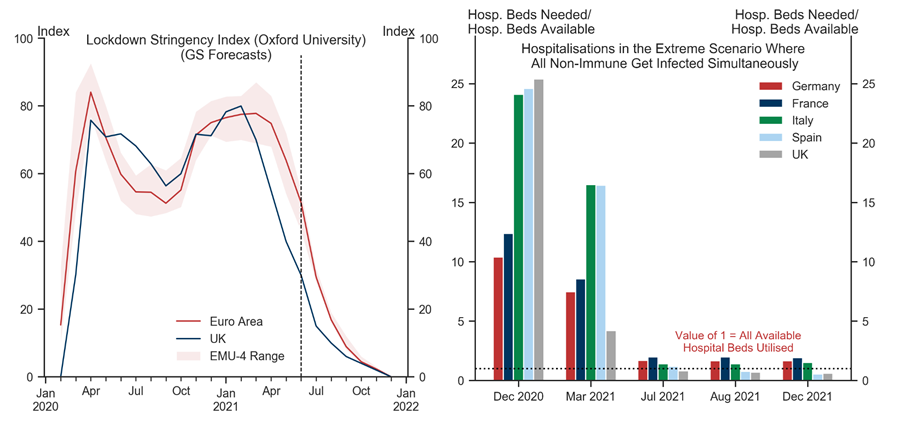

Q5. Has the delta variant increased the risk of renewed restrictions over coming months?

Cases: As we had argued above, we do see a risk of infections rising again in coming months, both in the UK and Euro area. That said, our analysis above points to limited evidence of significant persistent effects on consumer behaviour or labour availability from infections reaching levels we have seen in Europe over recent weeks. These effects could become larger if infections were to rise to much higher levels, in which case we would see scope for some targeted measures to be reimposed (e.g., limits on public gatherings or mass events, mask-wearing, or international travel), likely entailing only a modest economic cost.

Hospitalisations and/or fatalities: Our analysis suggests that even in a very severe and very unlikely scenario where each non-immune person was to become simultaneously infected, the pressure on hospitals would only modestly exceed available capacity.[9] Modelled scenarios by the UK's SAGE Institute also project hospitalisation outcomes that are well below (or no worse) than those from the winter wave, including in severe downside scenarios. We therefore think the risk of hospital overflow or elevated fatalities from here on is vastly lower than at any point since February 2020.

New variants: The potential emergence of new variants could take two forms. First, if a new highly-transmissive variant against which existing vaccines are nonetheless highly effective was to appear, its spread across Europe could cause some further delay to the recovery (depending on overall immunity levels at the point of its arrival). Second, if a new sufficiently-transmissive variant that is vaccine-resistant was to emerge, that could derail the recovery and remains the most severe downside risk in our view.

Exhibit 7: Lockdown Easing Under Manageable Risks

Nikola Dacic

- 1 ^ The 80-85% requirement follows by assuming the effective reproduction number is solely a function of (i) the basic reproduction number of the virus, and (ii) the non-immune share of the population. Assuming a basic reproduction number of the delta strain of around 5.0-5.5 (in line with existing estimates) implies that (at least) 80-85% of the population would need to be immune to ensure R stays below 1. For details, see Nikola Dacic, ''The Delta Variant—A Manageable Risk'', European Daily, 25 June 2021.

- 2 ^ See also Sid Bhushan, Dan Milo, and Daan Struyven, ''The End Game: Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy'', Global Economics Analyst, 1 June 2021.

- 3 ^ More formally, we find statistically significant effects (at the 1% level) of cases on mobility in a panel regression controlling for region and period fixed effects.

- 4 ^ The countries included are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Sweden, and Switzerland.

- 5 ^ Instead of using synthetic control methods (which attempt to match a number of 'pre-treatment' characteristics across the affected unit and the reference pool), we proceed by using regularised LASSO and Elastic Net regressions which allow for a large number of multicollinear regressors (as is the case in our application given strong co-movement of mobility across countries). Our estimation sample ranges from 1 May-1 July 2021. We show two versions: one with unconstrianed LASSO/Elastic Net parameters, and another in which (as part of the estimation) we impose a non-negativity constraint on all coefficients.

- 6 ^ Importantly, there hasn't been a further tightening of restrictions in the 'low-delta' reference pool of countries we consider over recent weeks. Otherwise, that could attenuate the implied scale of any behavioural effects due to high infections in the UK towards zero, as the slowing the pace of mobility improvements in the reference pool would then be partly restrictions-driven. We do not think this is the case given our choice of countries in the reference pool.

- 7 ^ Approaches to contact tracing vary across countries. See, for example, here for an overview of the contact tracing apps: https://www.liberties.eu/en/stories/trackerhub1-mainpage/43437.

- 8 ^ One example is the UK's industrial sector, where manufacturing output remains around 3% below pre-pandemic but the CBI survey points to record-highs in labour shortages.

- 9 ^ Recent data from the UK suggests some increases in hospitalisation rates (number of admissions per confirmed case) even among the elderly groups with very high vaccination rates (e.g., rising from around 2% to around 3% over the last few weeks in the over 50s). That said, the absolute numbers remain low and—relatedly—the sampling variation makes it more difficult to ascertain whether this is a trend increase and how persistent it could be (in case infections were to rise further). In any case, these hospitalisation rates remain far below those from the winter wave.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.