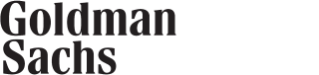

With the state- and individual-level July employment data now in hand, we estimate the impact of the early expiration of enhanced federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits in 25 states on employment, participation, and wages.

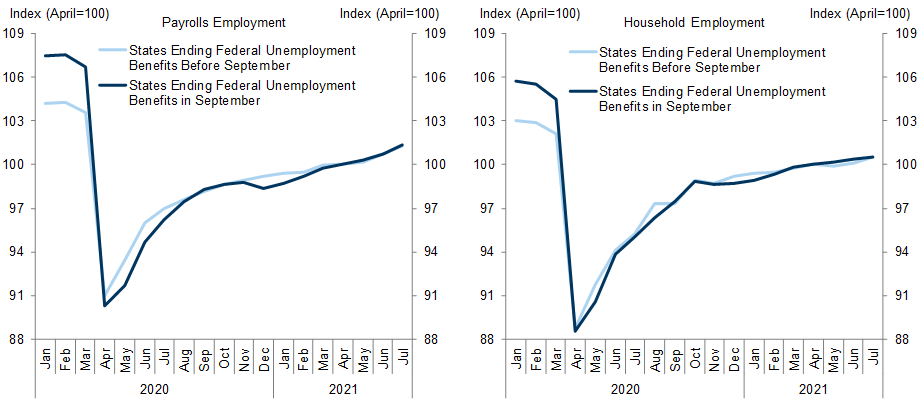

The state-level July payrolls figures do not show a statistically meaningful difference in job growth between states that ended UI benefits early and states that didn’t. But the more detailed individual-level data from the household survey of the employment report show clear evidence that benefit expiration increased the rate at which unemployed workers became employed.

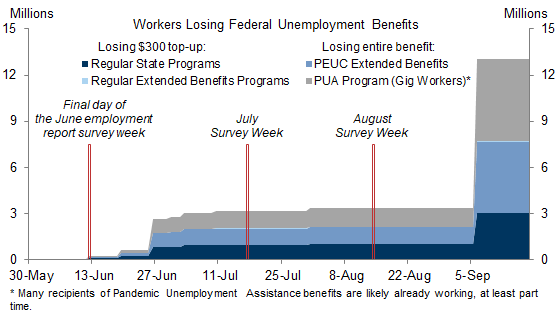

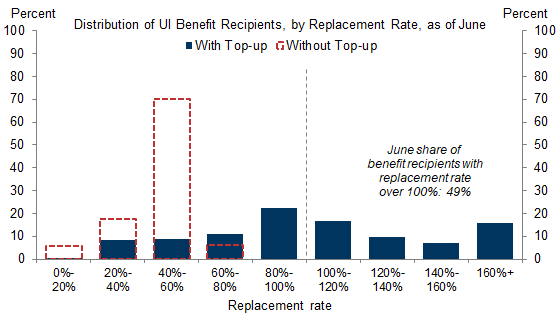

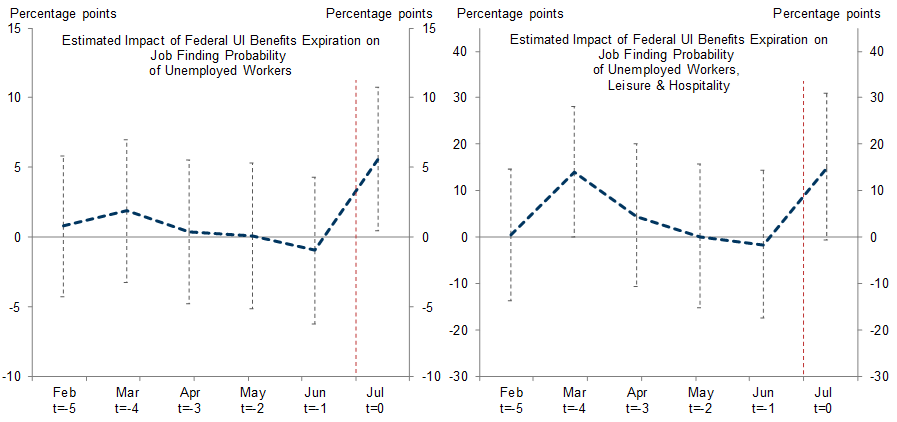

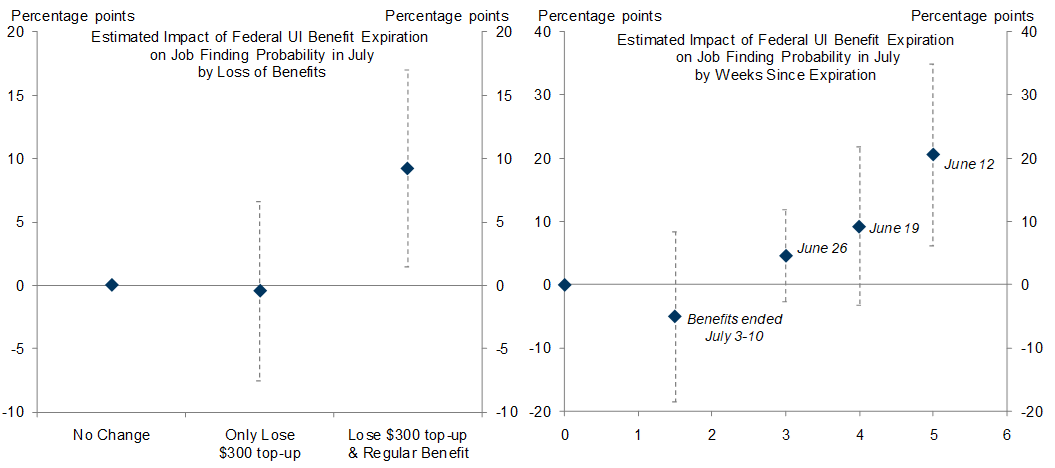

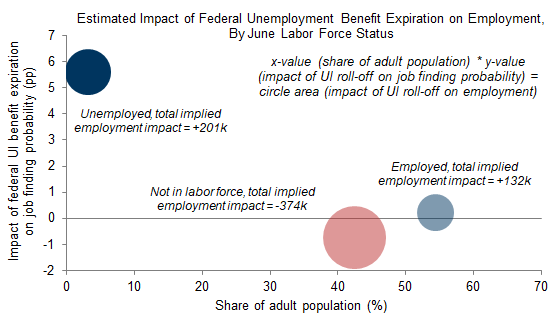

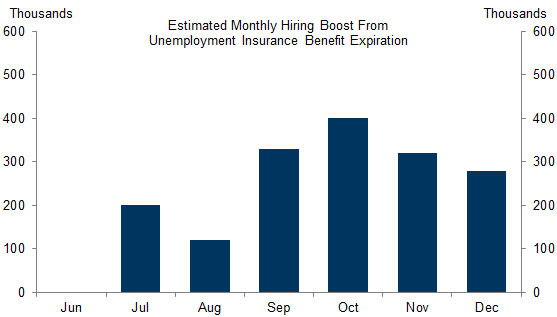

We make four key findings. First, UI benefit expiration increased unemployed workers’ job finding probability by 6pp (vs. an average job finding probability of 27%) in July. Second, the effect is larger for low-paid leisure and hospitality workers (+15pp). Third the effect is entirely driven by workers who lost all benefits (+9pp), while workers who just lost the $300 top-up were unaffected. Fourth, the effect increases over time and was only +5pp in states where benefits expired on June 26 but +21pp in states where benefits expired on June 12. New academic research supports our findings.

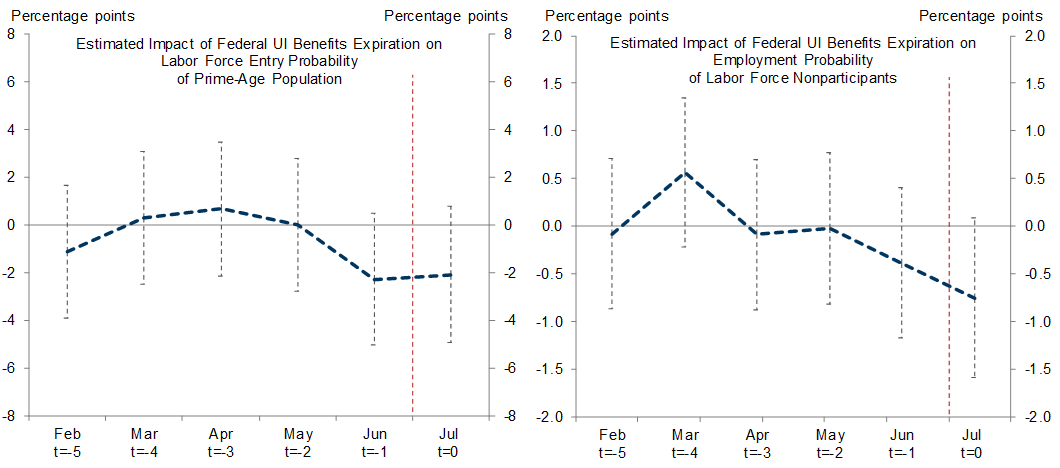

We find no evidence of a boost to labor force participation—in fact, the estimated effect is negative, but statistically insignificant. This suggests that many workers are staying out for non-financial reasons such as concern about Covid and may be slow to return to the labor force even after UI benefits end.

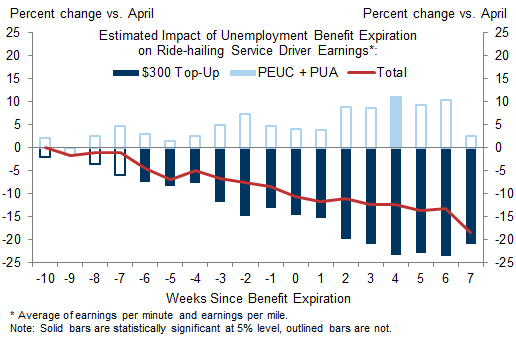

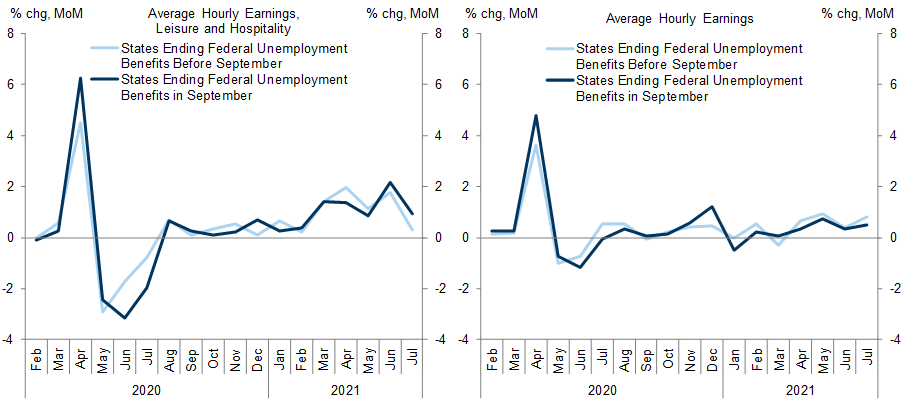

The impact of benefit expiration on wage growth remains inconclusive. We previously showed that wages for ride-hailing service drivers—where wages change dynamically in real time in response to increases in labor supply—have declined more in states that ended benefits early. Average hourly earnings growth in the leisure and hospitality sector was also softer in these states in July, although the difference is not statistically significant.

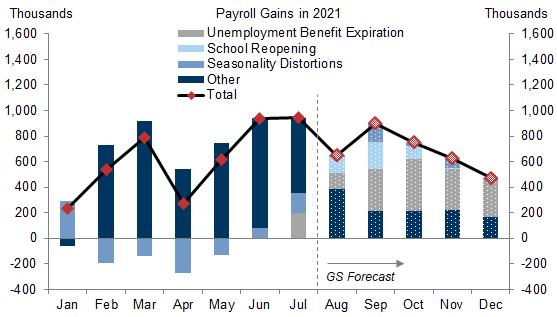

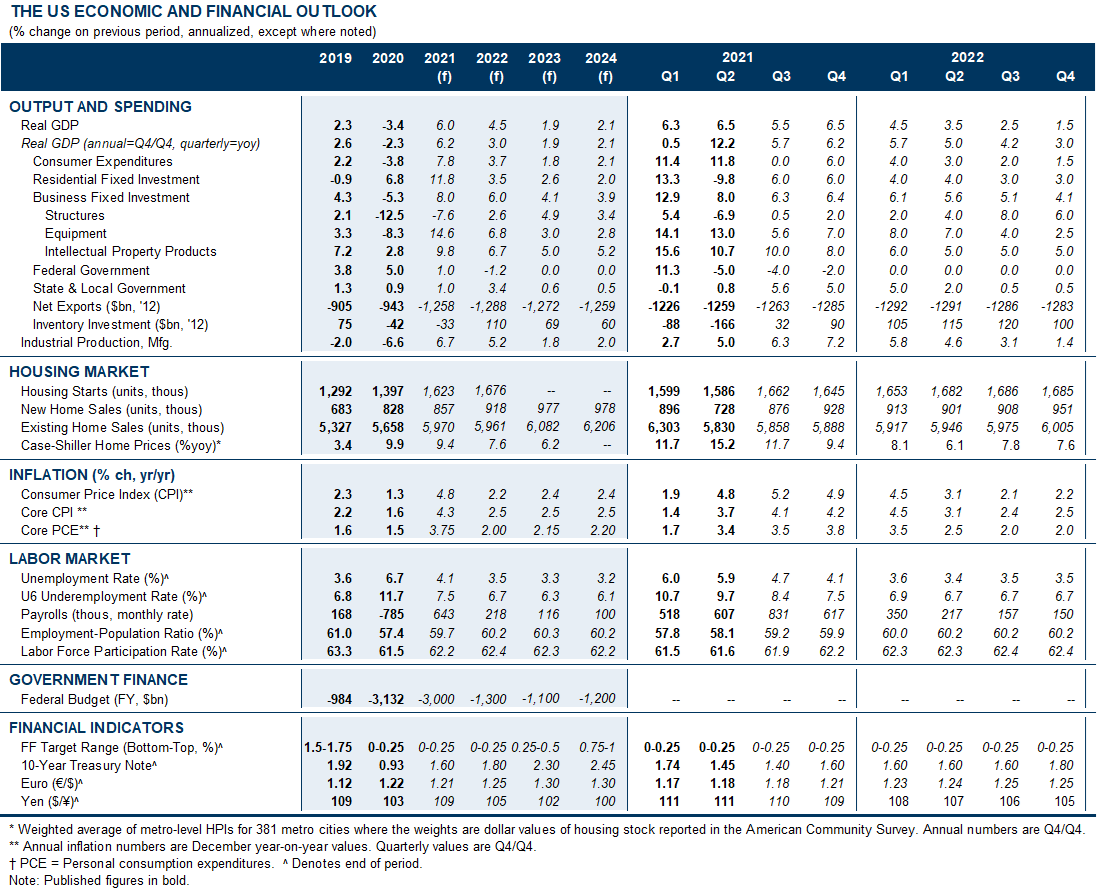

Our findings reinforce our confidence that national UI benefit expiration on September 6 will boost job growth by another 1.5mn through year-end. But they also suggest that it might take longer for the participation rate to recover. We continue to expect the unemployment rate to reach 4.1% by the end of 2021, but now expect the participation rate to only reach 62.2%.

Back to Work When Benefits End

Early Unemployment Benefit Expiration Increased the Incentive to Work

The Employment Effects of UI Benefit Expiration

The Effect of Benefit Expiration on Wage Growth

Updating Our Employment Forecast

Joseph Briggs

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ Kyle Coombs, Arindrajit Dube, Calvin Jahnke, Raymond Kluender, Suresh Naidu, and Michael Stepner, “Early Withdrawal of Pandemic Unemployment Insurance: Effects on Earnings, Employment and Consumption,” 2021.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.