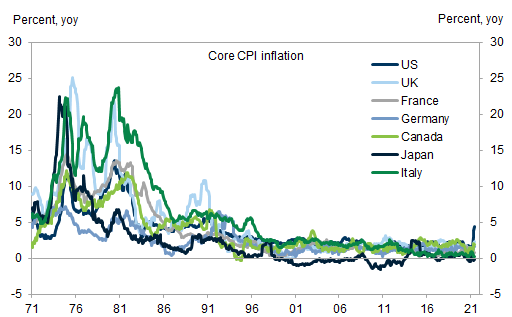

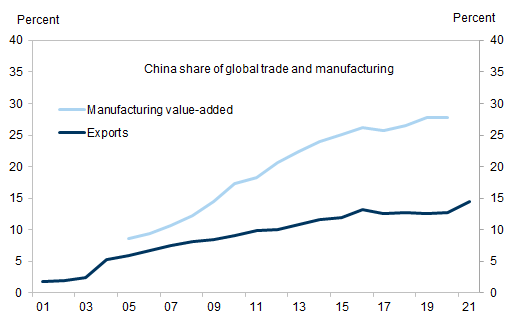

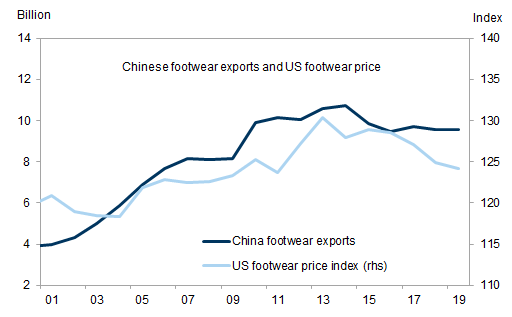

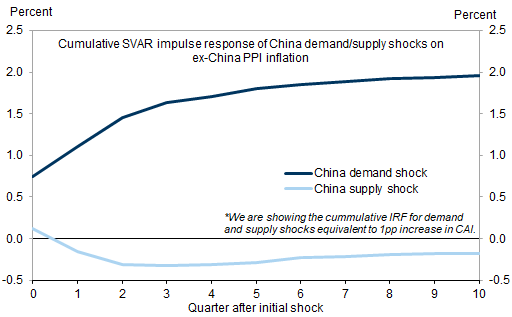

Globalization, and the rise of China’s manufacturing power after its entry into the World Trade Organization in particular, has been cited as one of the drivers behind the low and stable global inflation over the past two decades. With the Chinese government committed to de-carbonization and multinationals rethinking global supply chains after US-China tensions and the COVID pandemic, will China turn from a disinflationary force in the past into an inflationary driver in the future? We examine China’s role in global inflation in this note.

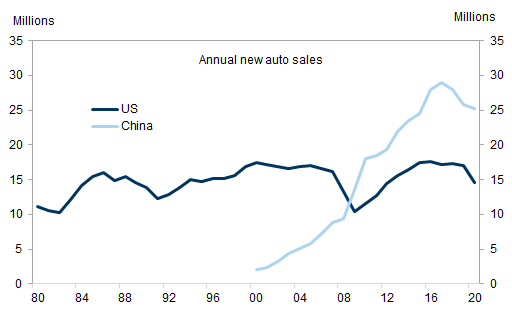

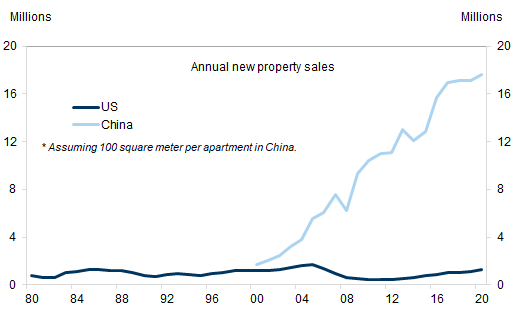

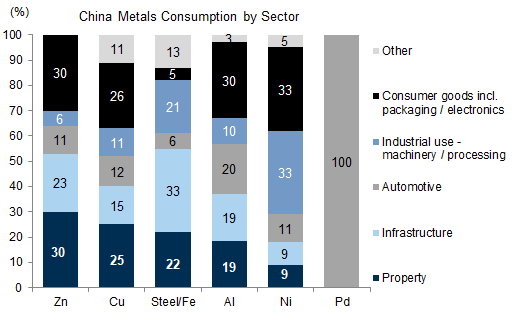

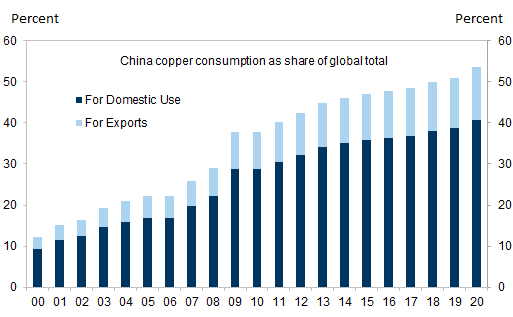

While discussions on the link between China and global inflation tend to focus on China supply, China demand plays an equally, if not more, important role. China accounted for almost all of the global metals demand increases over the past 20 years, and three quarters of that were for domestic consumption. The rapid expansion in infrastructure, property, and auto seen since 2000 is unlikely to be repeated. A gradual slowdown in demand growth, such as we expect, should be disinflationary rather than inflationary.

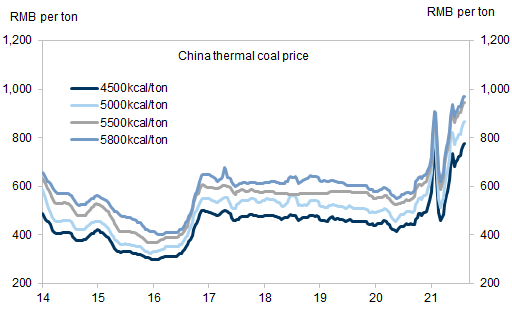

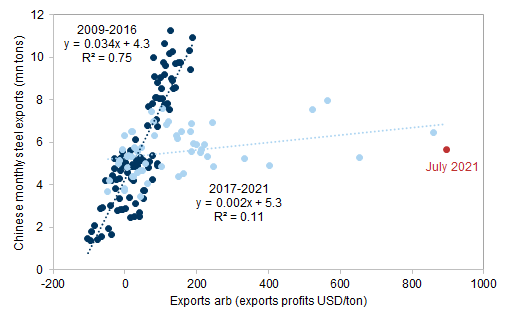

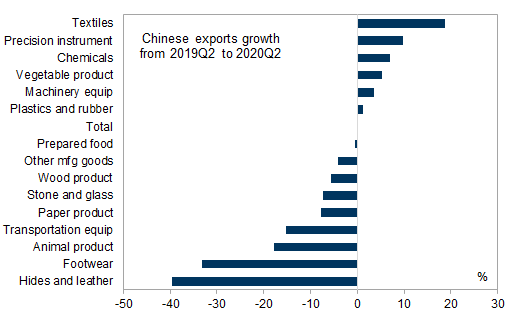

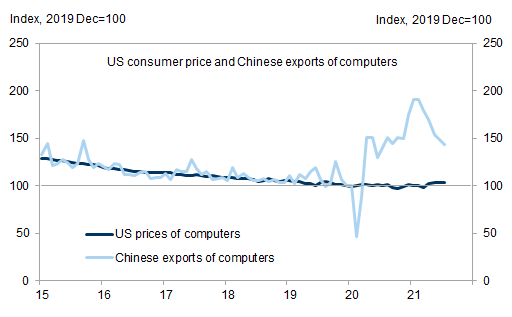

For upstream industries such as coal and steel, past capacity cuts to address overcapacity problems and production controls to improve air quality have led to low inventory and inelastic supply. Future de-carbonization moves are likely to keep these markets tight, resulting in high and volatile prices. But the downstream industries are entirely different. The experience of the COVID pandemic shows how flexible Chinese manufacturers can be, almost doubling exports of computers in a year on work-from-home demand surge for instance.

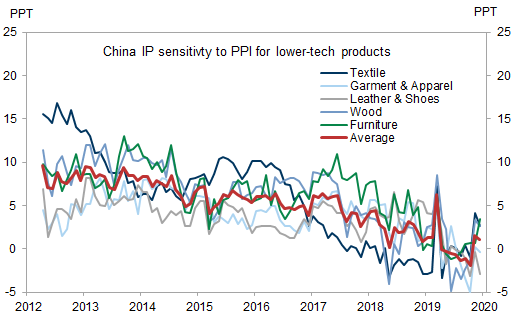

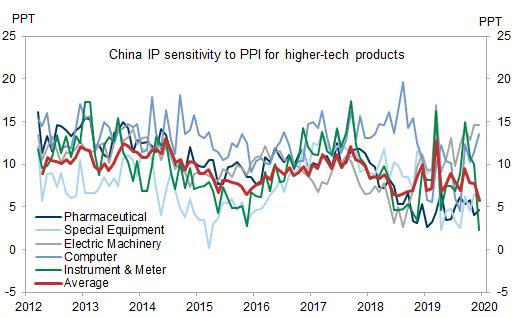

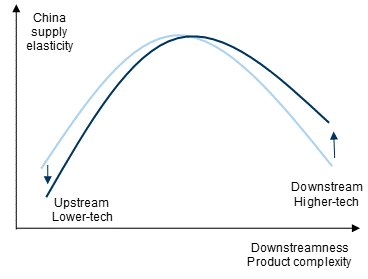

Within downstream industries, we observe a notable divergence between lower-tech sectors and higher-tech sectors. Supply elasticity in lower-tech sectors such as textiles and garment consistently trended lower during the 2010s while it stayed relatively stable in higher-tech sectors such as special equipment and electric machinery. Given the government’s emphasis on manufacturing upgrading in the 14th Five-Year Plan, supply elasticity in sectors such as semiconductors and new energy vehicles may increase in coming years with capacity expansion.

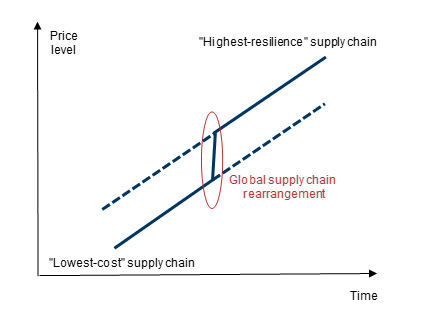

The combination of US-China tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic has led manufacturers to rethink input sourcing and supply chain resilience. A shift from a “lowest-cost” global supply chain to a “highest-resilience” one is undoubtedly inflationary in the near-term. However, the implication for inflation in the long run is ambiguous. In fact, if supply chains are indeed more resilient and less prone to disruptions, long-term inflation may even be lower on average as prices are less likely to spike on demand shocks.

The past and the future of China’s role in global inflation

The importance of China demand to global inflation

Exhibit 3: Auto sales in China exceeded those in the US after 2009

Exhibit 4: New property sales in China are about 15 times those in the US

Exhibit 5: Over half of China’s total steel, copper and aluminum consumption is in infrastructure, housing and automobile sectors

Exhibit 6: Three quarters of the growth in China’s copper demand over the past 20 years is for domestic use

Upstream and downstream moving in different directions

Exhibit 7: Coal prices are higher and more volatile now than before

Exhibit 8: China’s steel supply elasticity declined sharply after 2016

The divergence between higher-tech and lower-tech sectors

Differentiating short-term vs. long-term effects

Putting it together

- 1 ^ See Kristin Forbes 2019, “Inflation Dynamics: Dead, Dormant, or Determined Abroad?” NBER Working Paper 26496 for example.

- 2 ^ Most of the automobiles produced in China are for domestic consumption rather than exports. In 2019, for example, China produced 25 million cars and exported 1 million, according to official statistics.

- 3 ^ 50% is a generous assumption because NBS data show that “value of industrial export delivery” to “gross output value of industry” ratio peaked at 20% in 2004. Industry contacts suggest about one-third of home appliances produced in China are for exports.

- 4 ^ Note that using lagged price changes alleviates, but not completely removes, the endogeneity problem which biases supply elasticity estimates downward. In addition, because PPI growth could be zero, we cannot use the ratio of IP growth to PPI growth.

- 5 ^ This diagram draws from Professor Markus Brunnermeier at Princeton University in his discussions of global supply chains and inflation.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.