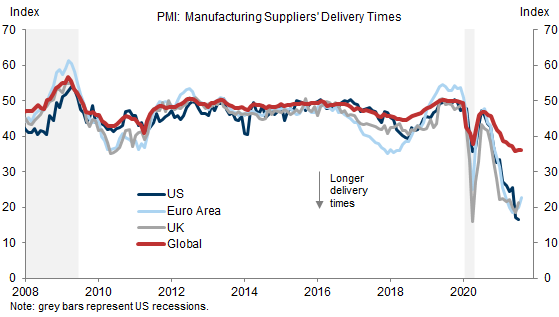

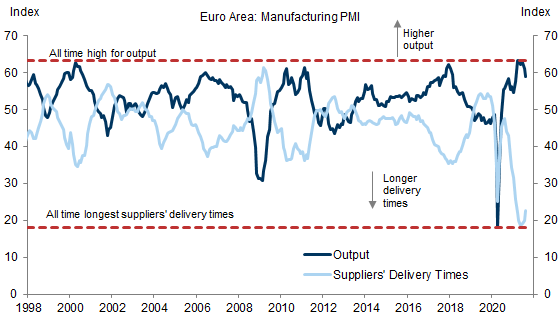

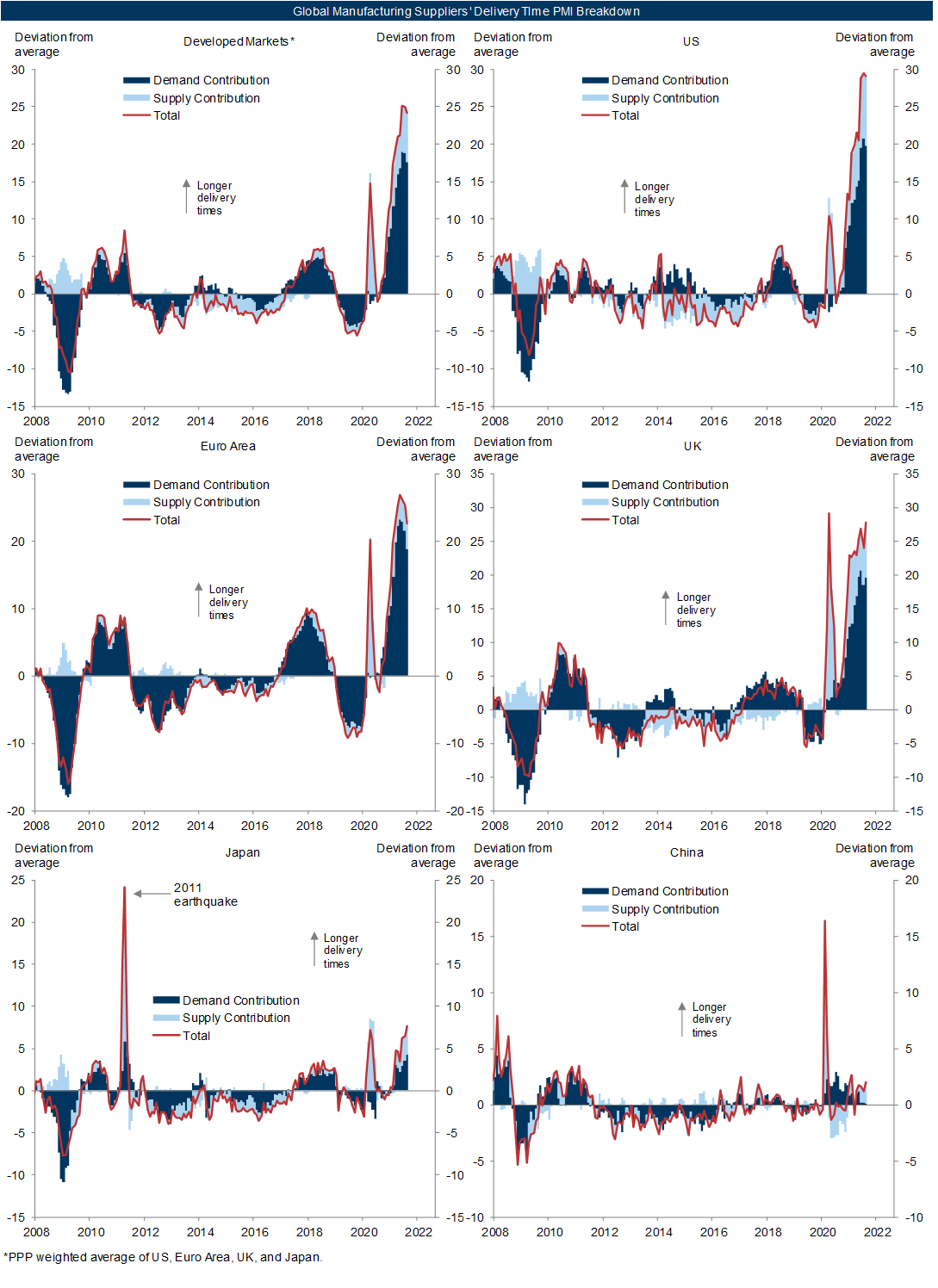

Global manufacturing supplier delays have intensified further to extreme levels, especially in the US and Europe. Supply chain issues have substantially contributed to the downgrades to our 2021Q2 and 2021Q3 US growth forecasts, and have led to major global upside inflation surprises. What lies behind these supply chain stresses and how will their evolution affect global growth and inflation?

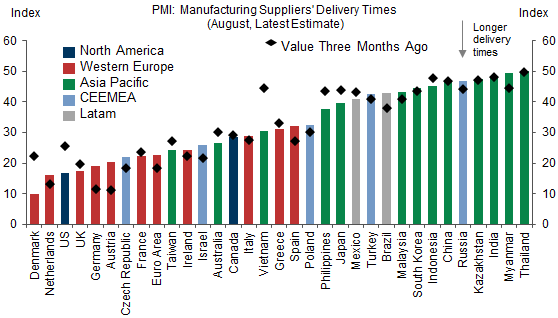

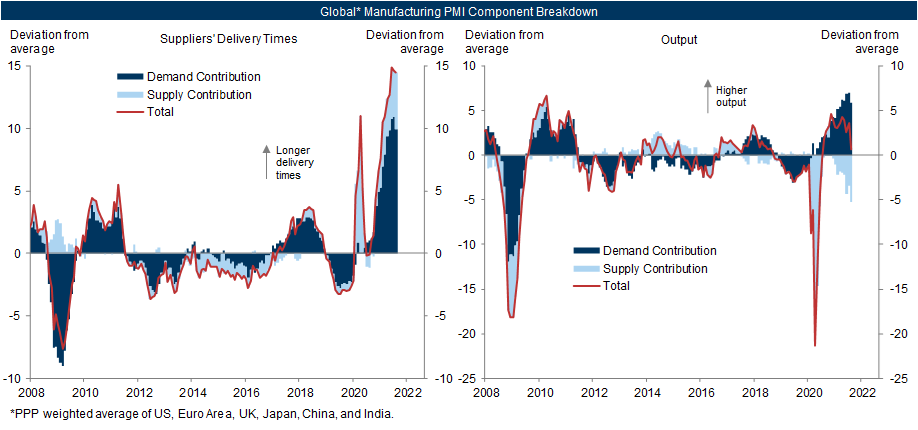

We estimate that strong goods demand currently accounts for about two-thirds of the global manufacturing delays. While weak supply led to delays and depressed output last spring, the global manufacturing PMI output index remains firm now, indicating an overwhelming role for the demand side. The exception is Asia, where weakness in supply, partly related to virus disruptions, plays a larger role.

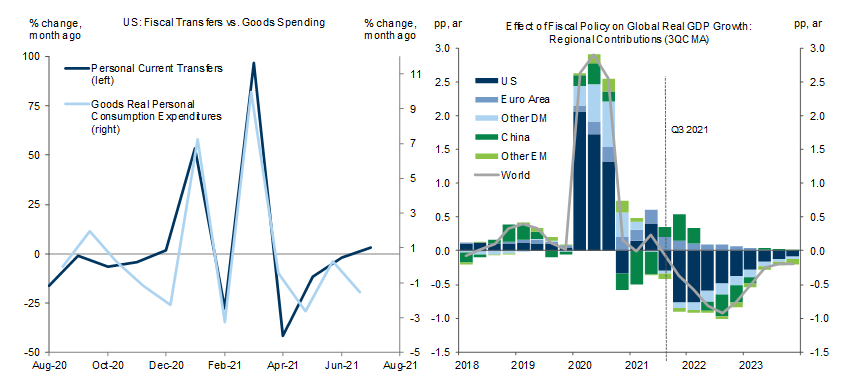

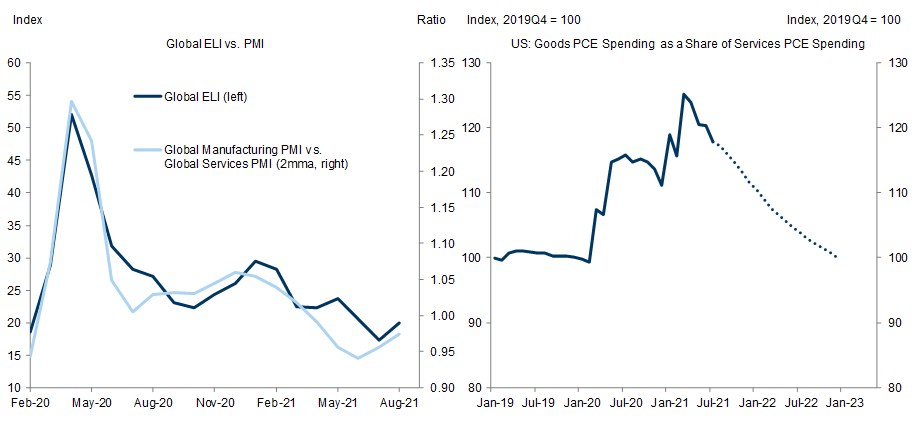

A moderation in goods demand over the next year should sharply reduce manufacturing delays, although a decline in virus-related disruptions to global and especially Asian goods supply should help too. We expect goods demand to moderate as the global fiscal impulse turns negative, and as spending gradually rotates back from goods to services assuming the virus situation improves. That being said, structurally strong tech demand and the slow speed at which semiconductor production capacity can be increased suggest that the easing of shortages for chips (and therefore cars) will take longer than for other constrained goods.

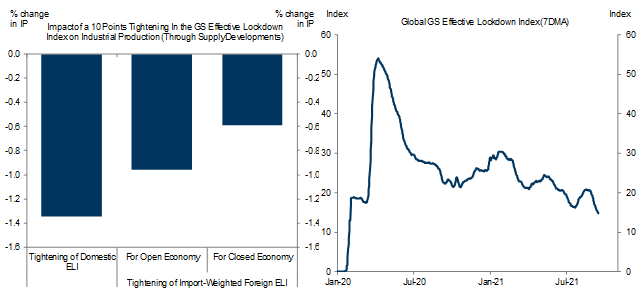

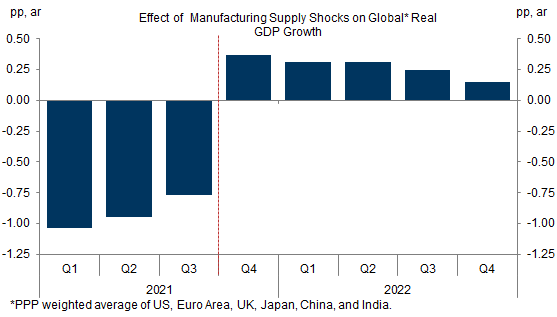

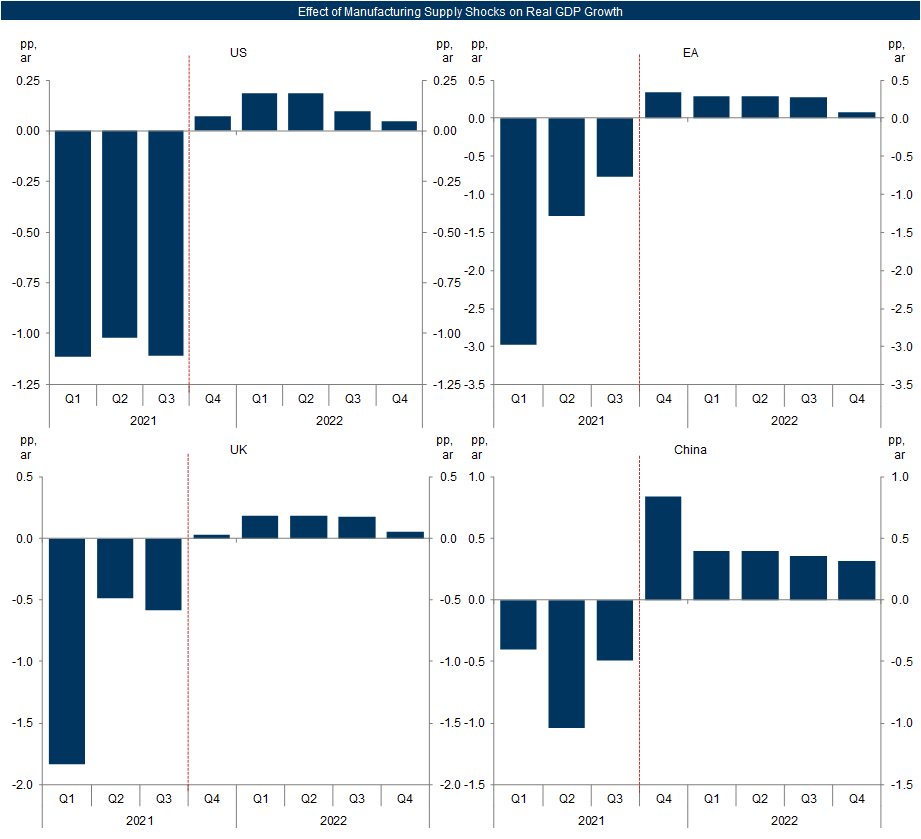

Assuming a gradual normalization in our GS effective lockdown index, we estimate a swing in the manufacturing supply impulse to global growth from roughly -1pp so far this year into slightly positive territory in coming quarters.

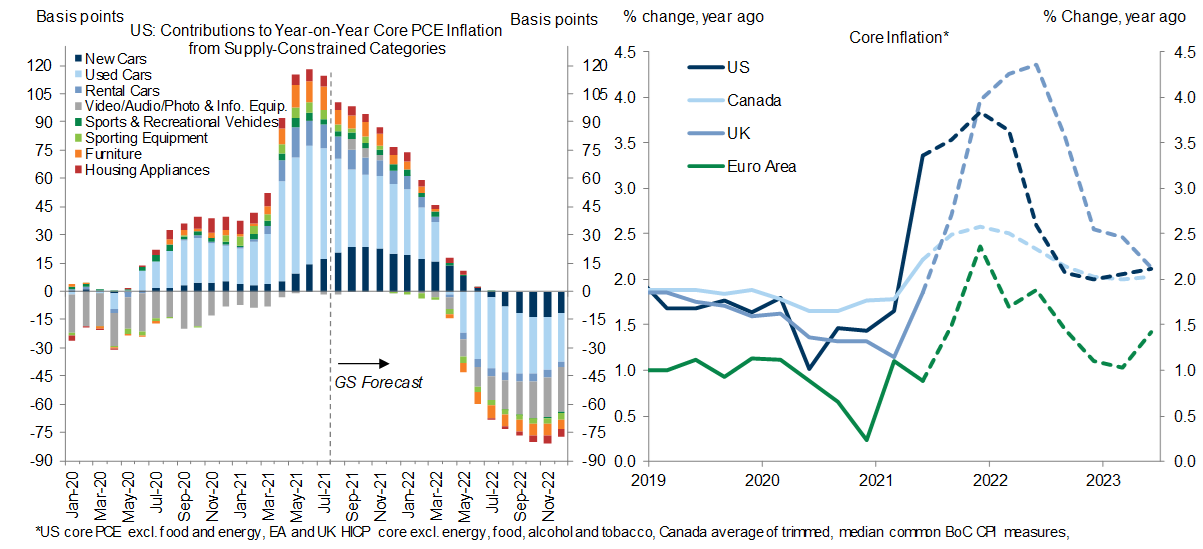

The expected moderation in global goods demand and the virus-driven improvement in goods supply help bring down inflation to more normal levels. We expect core inflation to fall back by 2022Q4 to 2.5% in the UK, 2.0% in the US and Canada, and 1.1% in the Euro Area.

Supply Chains, Global Growth, and Inflation[1]

It’s Mostly Demand

Less Virus, More Manufacturing Supply

Less Virus, Moderating Goods Demand

Factor 1: Global Fiscal Impulse Turns Negative

Factor 2: A Shift Back to Services

Caveat: A Semi-Persistent Tech Boom

Supply Shocks, Growth, and Inflation

Sid Bhushan

Daan Struyven

- 1 ^ The authors would like to thank Nikola Dacic for his contributions.

- 2 ^ For instance, disappointing inventory formation, in turn largely reflecting supply chain issues, has contributed 2.0pp of the 3.9pp downgrade to our US 2021Q2 annualized GDP growth estimate since the last week of May.

- 3 ^ See Nikola Dacic, "The Cost of Supply Chain Disruption", European Daily, 12 March 2020.

- 4 ^ See Andrew Tilton, "Supply chain stresses", Asia in Focus, 15 September 2021.

- 5 ^ Specifically, we assume that countries in the high risk aversion group (see Exhibit 6 here) reach an ELI of 5 by the end of 2022Q4, countries in the middle risk aversion group reach an ELI of 3.75 by the end of 2022Q3, and countries in the low risk aversion group reach an ELI of 2.5 by the end of 2022Q2. We interpolate linearly between current ELI levels and the end point.

- 6 ^ The estimated improvement in the manufacturing supply impulse to Chinese growth reflects the assumed improvement in the global virus situation and does not capture the current stress in Chinese supply chains related to raw materials, driven by its more persistent decarbonization push.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.