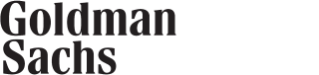

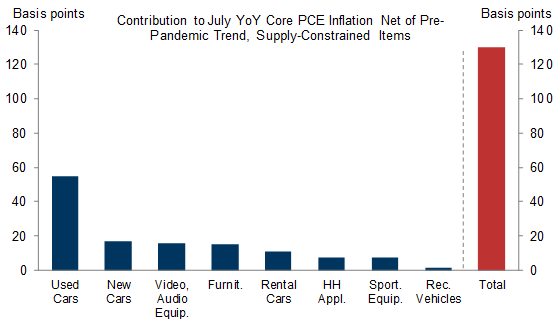

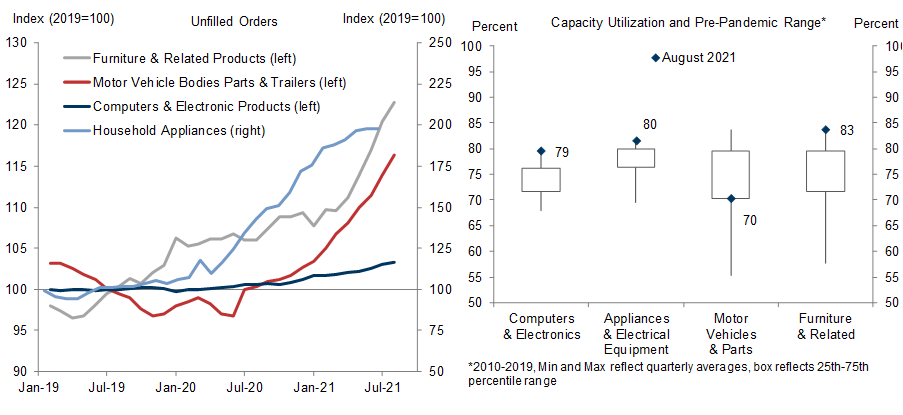

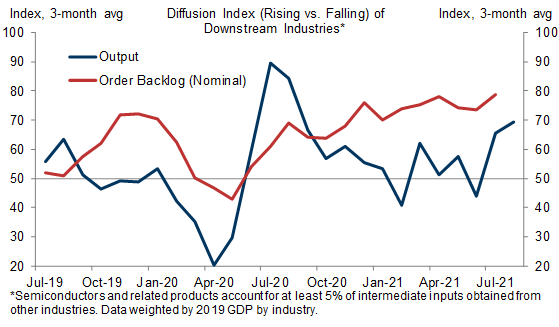

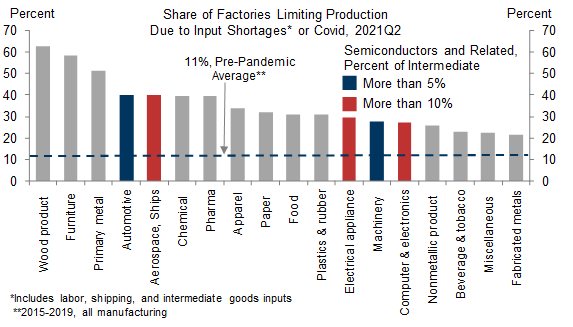

Supply-constrained goods account for 80% percent of the 2021 inflation overshoot, owing largely to historic supply chain disruptions and other constraints on production. Exploring company-reported bottlenecks in the quarterly supplement of the industrial production report, we find that shortages of labor and intermediate goods inputs are the key constraint on the manufacturing sector, with the share of factories limiting production due to input scarcity nearly tripling in Q2 relative to pre-crisis.

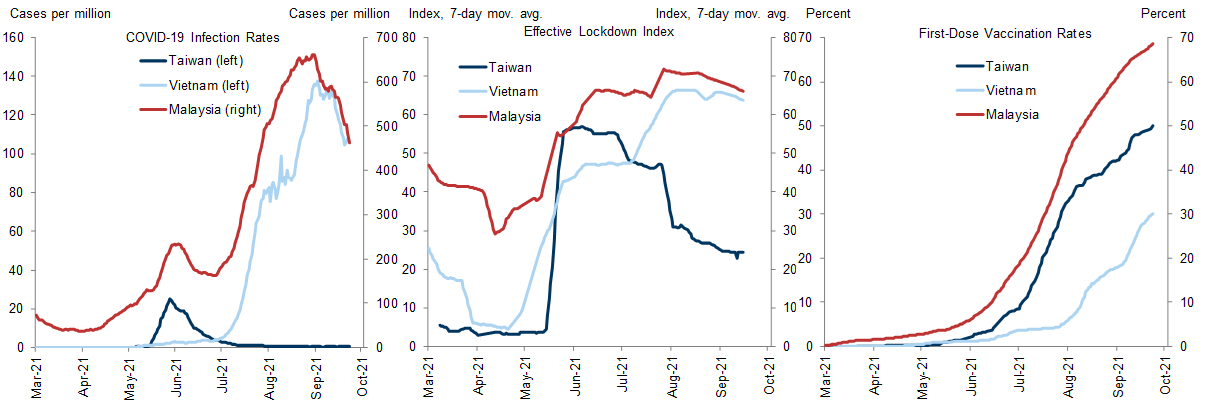

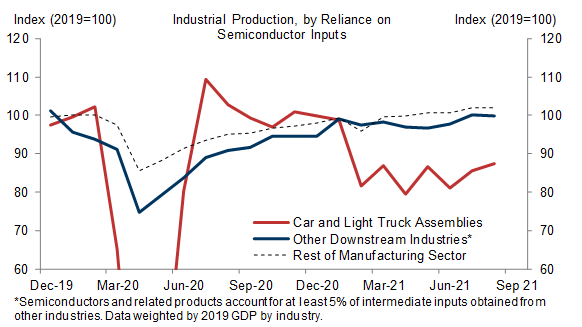

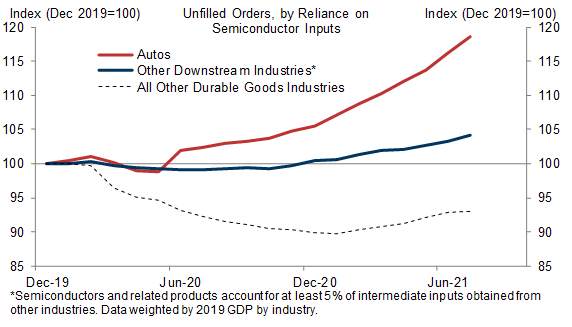

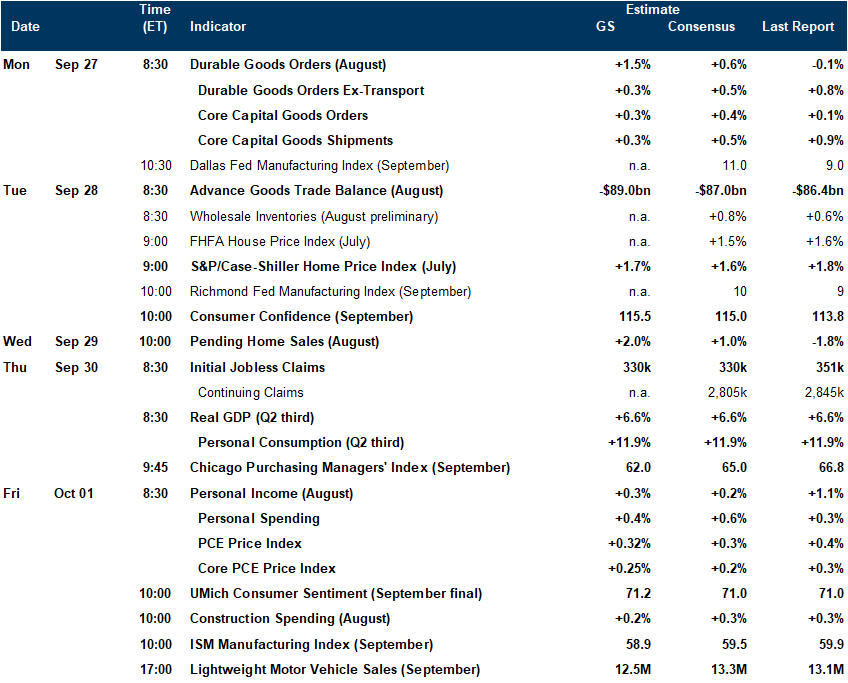

One key input in short supply is microchips. The shortage appears to be worsening again, with plant shutdowns in Southeast Asia leading US automakers to slash September production. Looking ahead, the sharp rise in vaccination rates and the tentative decline in lockdowns in the region are both encouraging, but we are nonetheless pushing back our assumption for improving chip supply from this fall to 1H22.

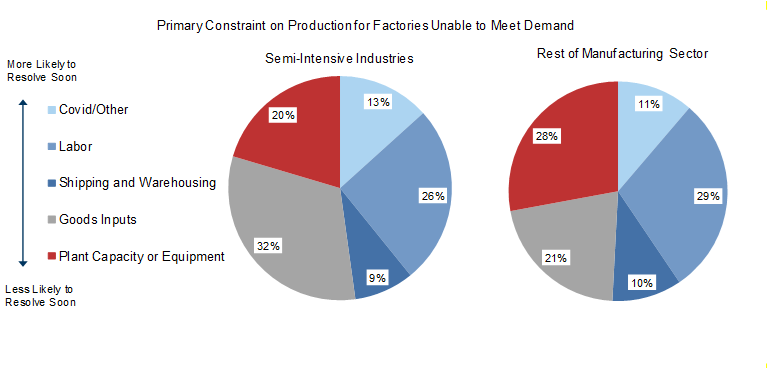

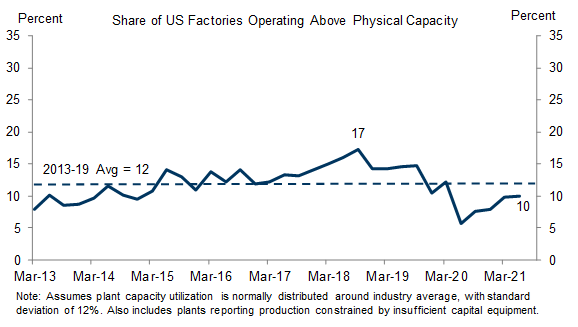

Beyond that, the news is more encouraging. Only a quarter of manufacturing supply constraints reflect the combination of excess demand and underinvestment that is traditionally associated with persistent economic overheating. And even in segments with rapidly rising prices, we find that the equipment and structures currently in place could accommodate increases in production once labor and input supply increases.

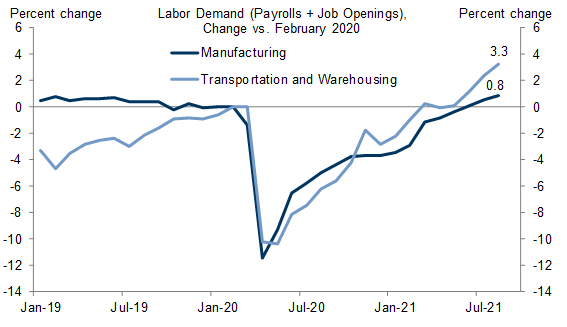

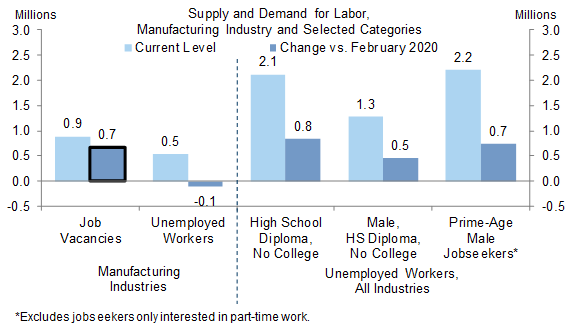

We also find that labor, shipping, and covid together account for roughly half of reported production constraints in US manufacturing, and we expect all three supply headwinds to ease in coming quarters. Demand for labor in the manufacturing and transportation sectors is only modestly above pre-crisis levels (+1% and +3%, respectively), and there are enough unemployed high school graduates and prime-age-males looking for full-time jobs to fill the majority of the 700k factory-worker shortages.

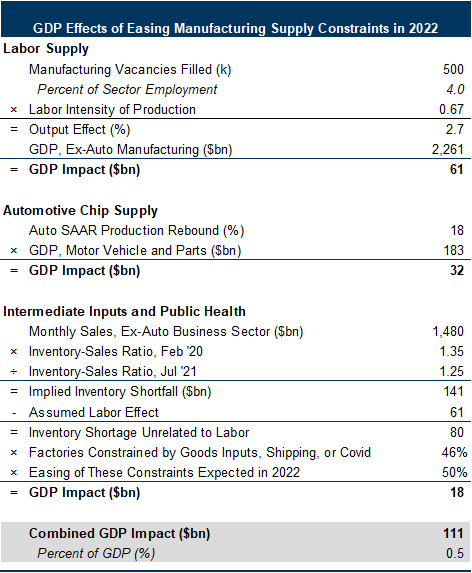

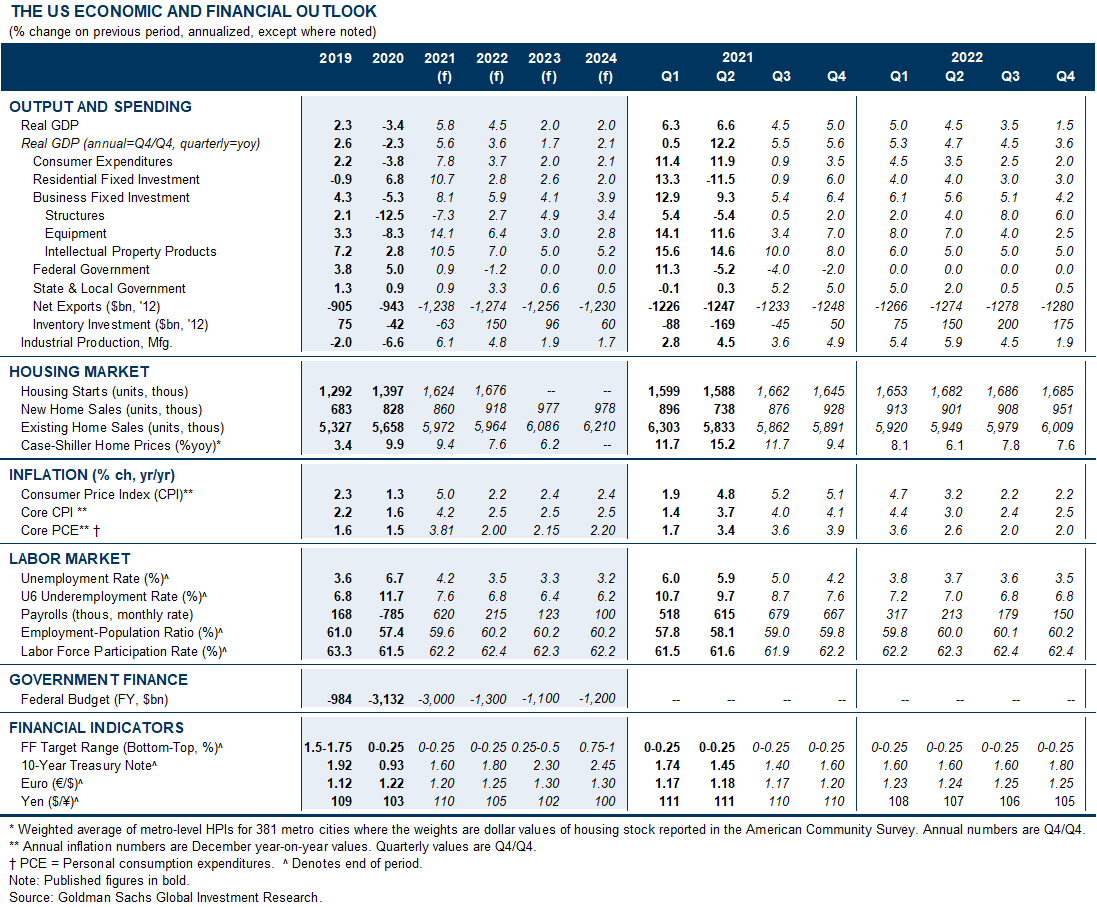

Taken together, we estimate that normalizing labor supply and sequential improvement in microchip availability will boost manufacturing output by $100bn and contribute +0.5pp to GDP growth in 2022 (Q4/Q4). That being said, the uncertain timing of both the auto production rebound and the labor supply normalization raises the risk that economy-wide restocking could be minimal or even negative during the fall and winter.

From an inflation perspective, continued drawdowns in auto inventories this fall coupled with shortages of electronics, furniture, and other consumer products argue for upward pressure on core goods prices during the holiday season. Large price declines for semiconductor-dependent categories also no longer appear likely in the short-run.

Good News and Bad News for the Manufacturing Supply Rebound

How the Delta Wave Worsened the Global Microchip Shortage

Shortages of Labor and Other Inputs

The Scope for Easing Supply Constraints

Spencer Hill

Appendix

- 1 ^ Some plants can temporarily operate above 100% capacity, for example by paying unsustainably high prices for overtime labor.

- 2 ^ September and Q4 supply has also been impacted by ‘hoarding’ on the part of customers in an uncertain environment.

- 3 ^ An additional 200k males want a job but have left the labor force specifically because of the pandemic.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.