Worker shortages have slowed the labor market recovery and put significant upward pressure on wages in 2021. In this US Economics Analyst, we explore the underlying causes of these labor shortages and when they will likely resolve.

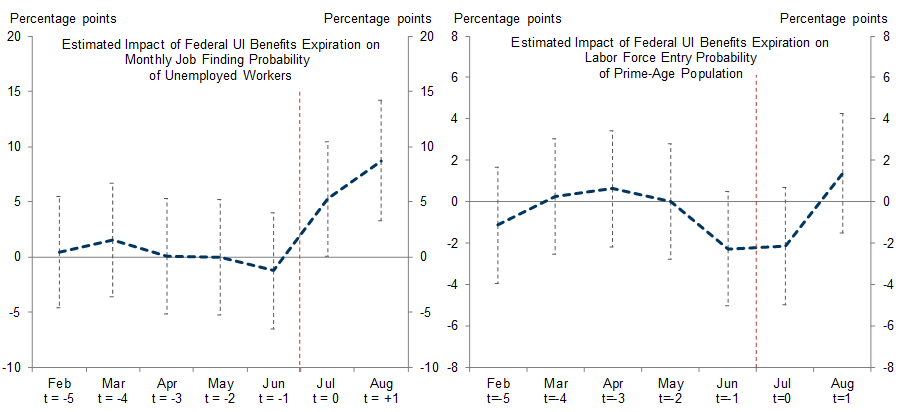

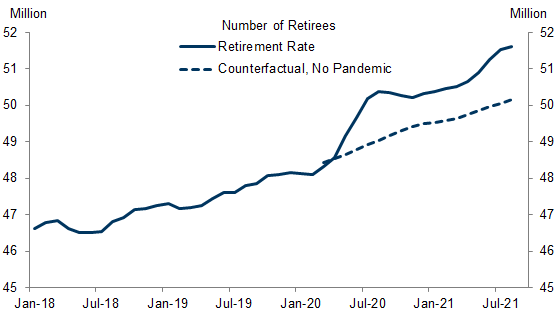

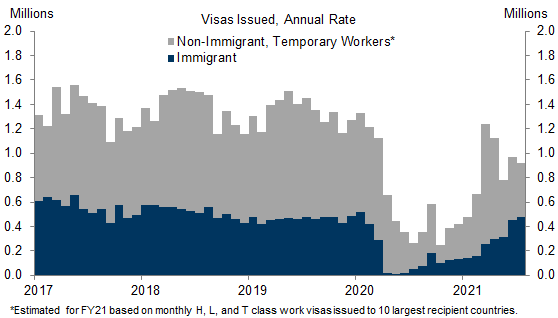

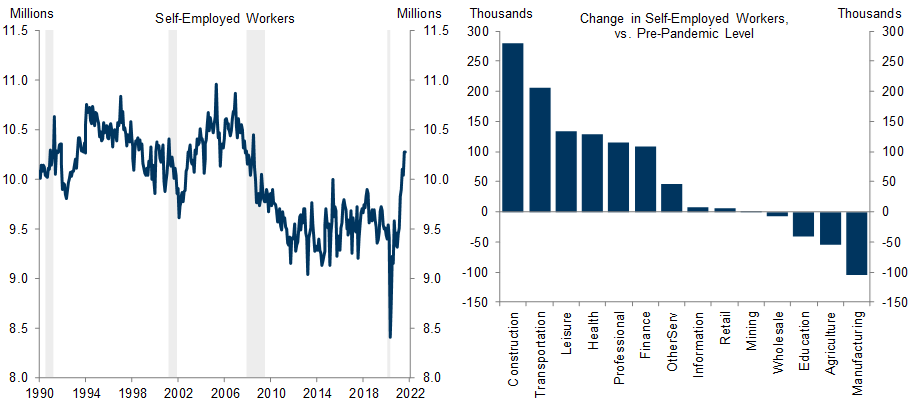

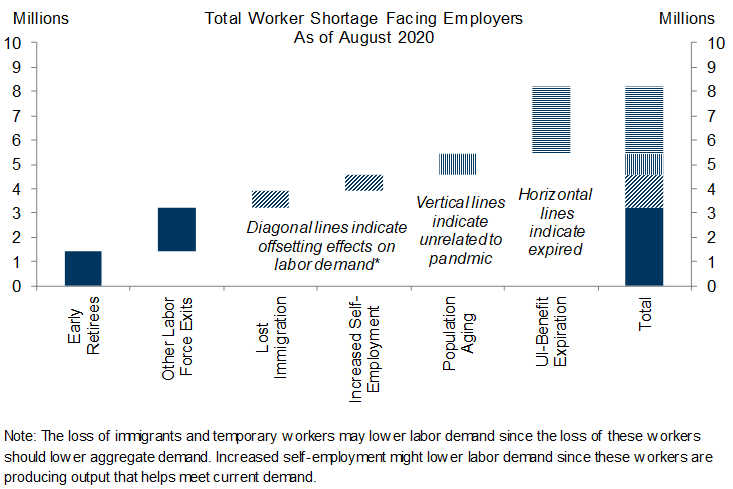

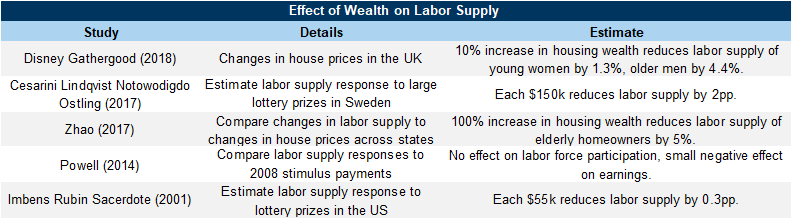

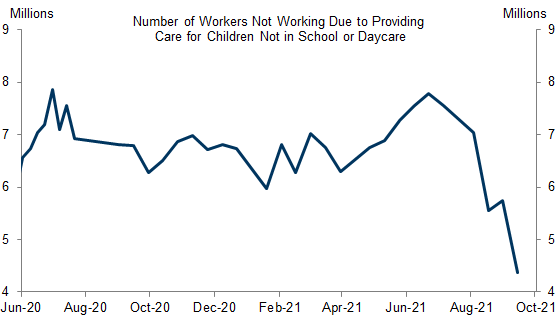

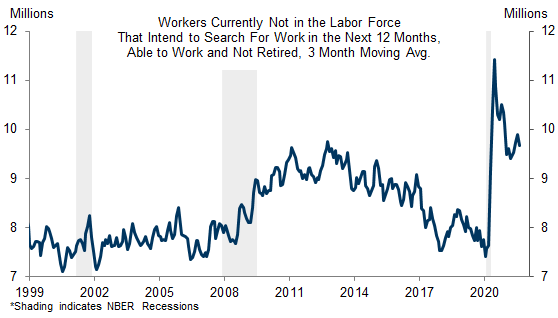

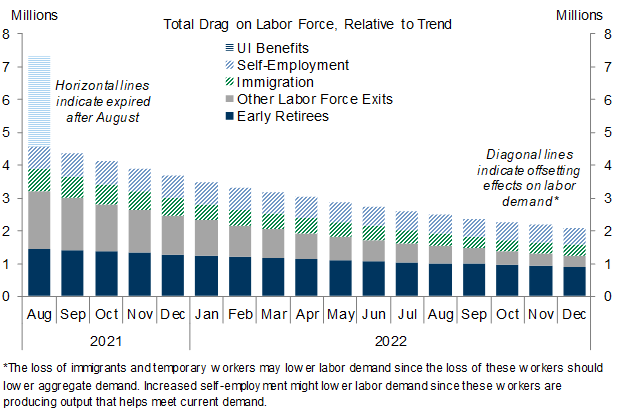

The labor shortage facing employers has reflected a perfect storm of labor supply disincentives from generous federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, early retirements, population aging, other labor force exits, a collapse in immigration, and increases in self-employment during the pandemic. Combined, these factors had lowered the pool of prospective employees by over 8mn through August, of which 5.6mn will persist after federal UI benefits expired in September.

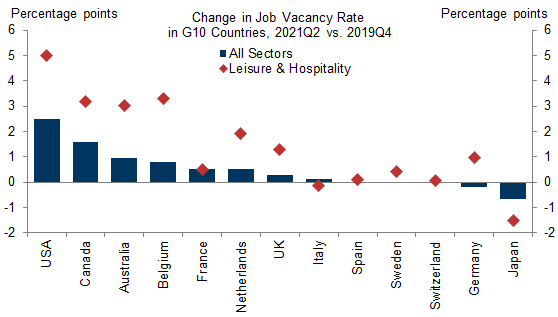

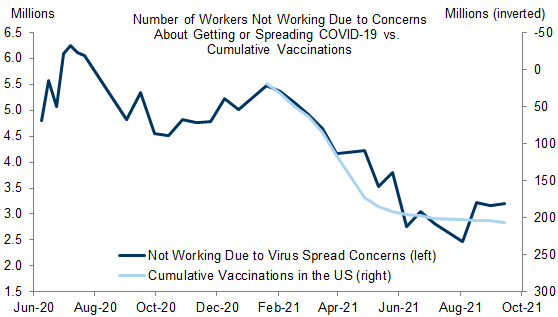

While generous UI benefits have contributed to the labor shortages, reports of labor shortages are widespread across developed economies, suggesting that common global factors—for example, elevated health risk—also play significant roles. The good news is that aside from retirees nearly all new labor force nonparticipants still view their exits as temporary and expect to start searching for work within the next year. We therefore expect that the current labor shortage will ease considerably going forward, but still project an over 1mn hit to the labor force relative to trend at end-2022 from early retirements and other labor force exits during the pandemic.

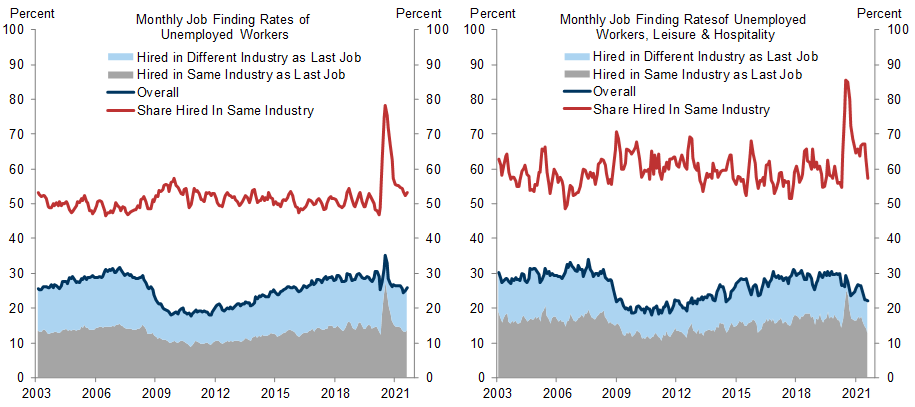

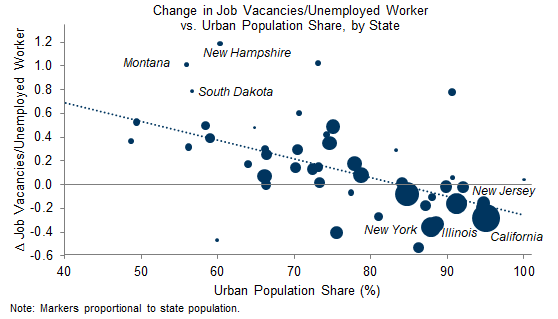

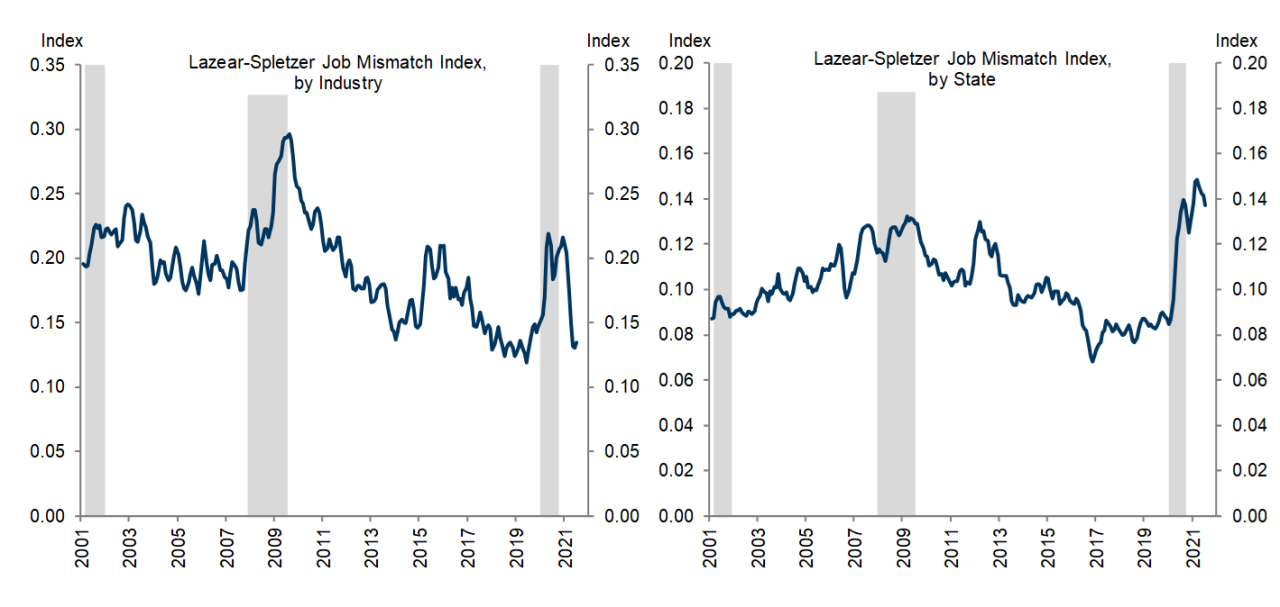

In addition to reduced labor supply, labor shortages could also reflect mismatch between the jobs workers are looking for and the jobs that are available. While mismatch across industries increased during the pandemic, mismatch across geography soared to an all-time high as labor demand has shifted away from urban areas. Mismatch should moderate as offices and cities continue to reopen, but will likely remain elevated as some of the pandemic-driven shifts in economic activity prove persistent.

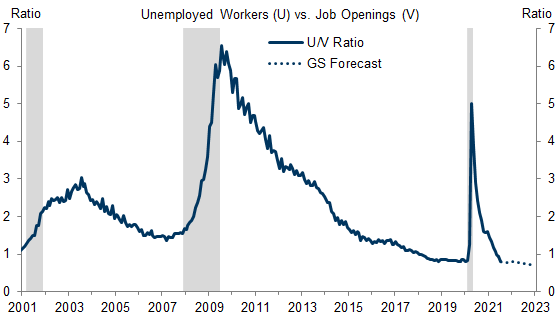

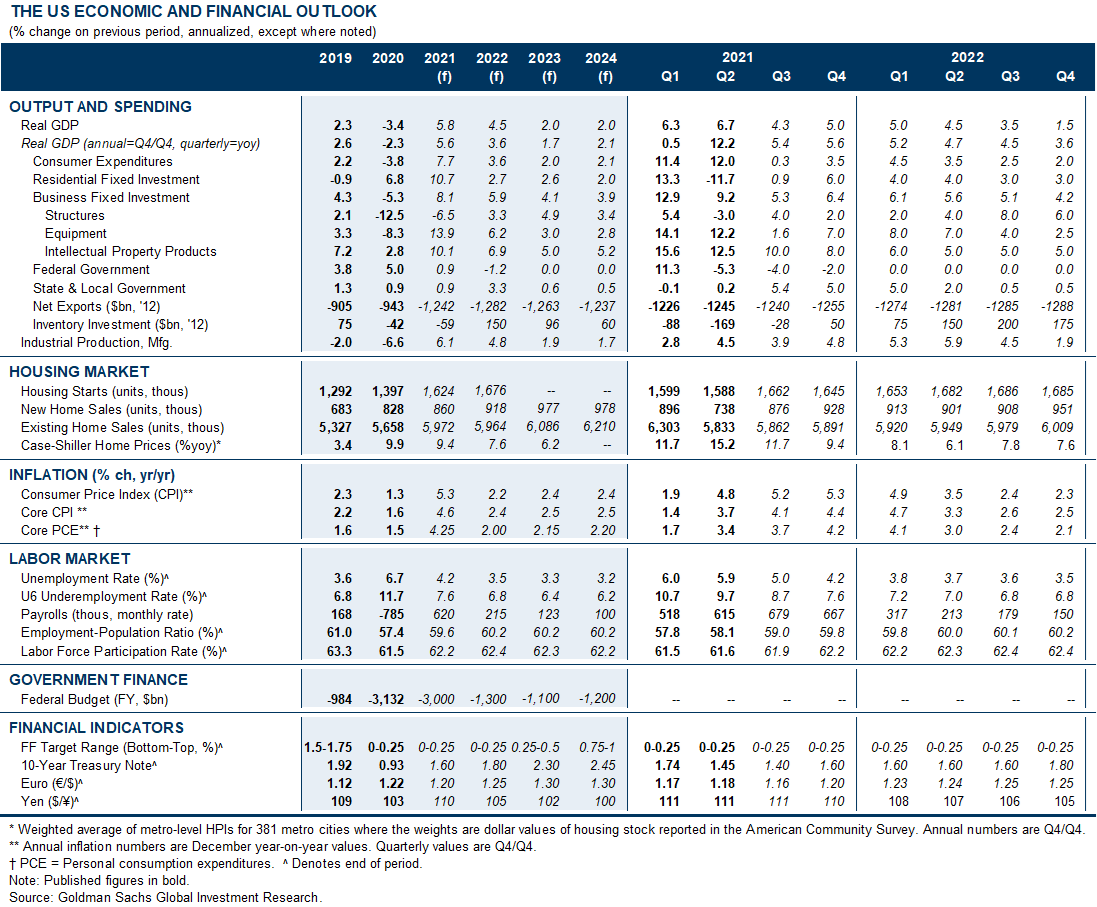

Although we expect labor-market shortages to ease going forward, early retirements, the 2020 immigration collapse, and lingering mismatch will likely mean that a 3.5% unemployment rate—our forecast for end-2022—would imply a tighter labor market than it did last cycle. As a result, we expect wage growth will remain at about 3¾% in 2022, stronger than it was last cycle.

Will Worker Shortages Be Short-Lived?

A Perfect Storm of Worker Shortages

What Are the Underlying Causes of Worker Shortages, and When Will They Reverse?

Labor Force Mismatch

Labor Market Tightness Going Forward

Joseph Briggs

- 1 ^ Autor, David. “Good news: There’s a labor shortage”. NY Times. Sep 4, 2021.Davidson, Paul. “Breaking down the big US labor shortage: Crunch could partly ease this fall but much of it could take years to fix.” USA Today. Sept 7, 2021.Morath, Eric. “Millions are unemployed: Why can’t companies find workers?”. The Wall Street Journal. May 6, 2021.

- 2 ^ Solomon, David and Kenneth Adams. “One way to help solve the nation’s labor shortage”. CNN. 10/1/2021.

- 3 ^ Hurst, Erik, and Ben Pugsley. "The non pecuniary benefits of small business ownership." University of Chicago working paper. 2010.

- 4 ^ Sisson, Patrick. “One Solution to a Shortage of Skilled Workers? Diversify the Construction Industry.” NY Times. September 25, 2021.

- 5 ^ Furman, Jason, Melissa Schettini Kearney, and Wilson Powell. “The Role of Childcare Challenges in the US Jobs Market Recovery During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” No. w28934. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021.

- 6 ^ Ramani, Arjun, and Nicholas Bloom. “The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w28876. 2021.

- 7 ^ Lazear, Edward P., and James R. Spletzer. "The United States labor market: Status quo or a new normal?". No. w18386. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2012.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.