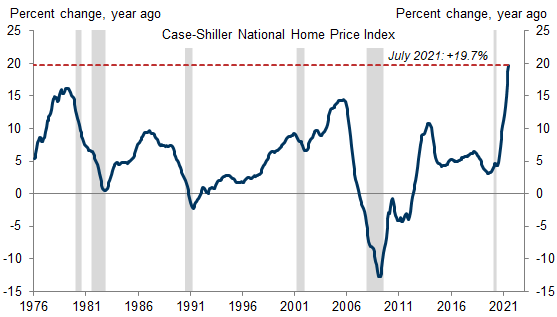

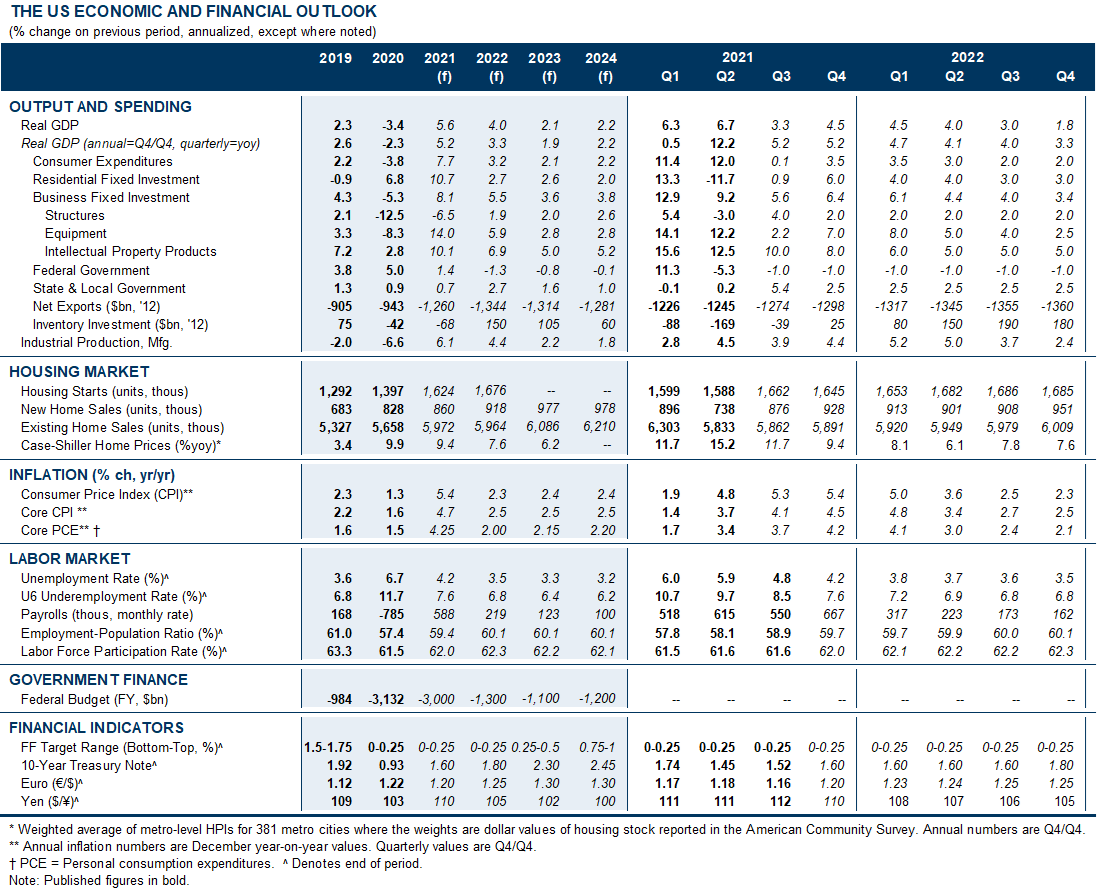

Of all the shortages afflicting the US economy, the housing shortage might last the longest. Earlier this year, we argued that constrained supply and sustainably robust demand would keep the US housing market very tight, pushing up home prices and rents sharply. The boom since then has surpassed even our lofty expectations, with home prices now up 20% over the last year. This week, we take stock of where home prices will go from here, how high rent inflation will rise, and whether new deregulatory efforts can alleviate the housing shortage.

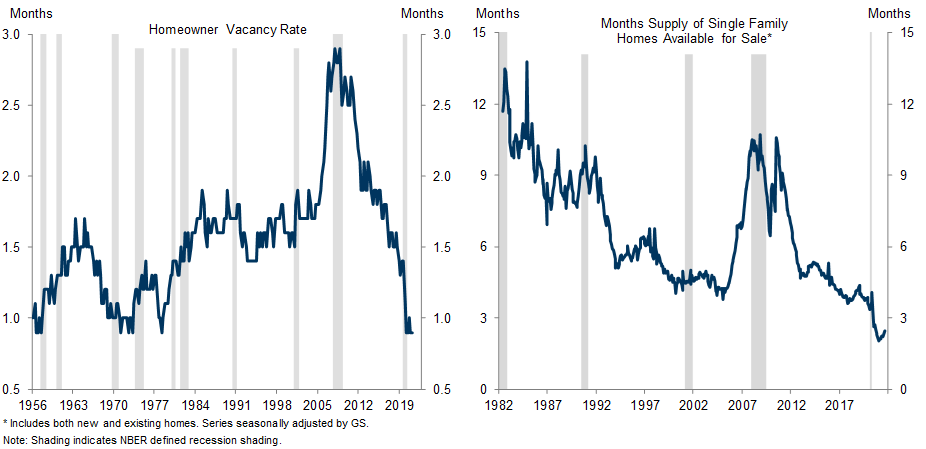

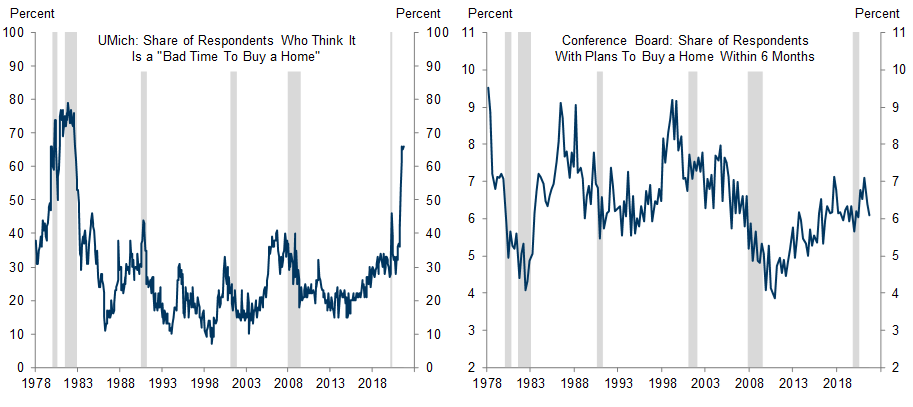

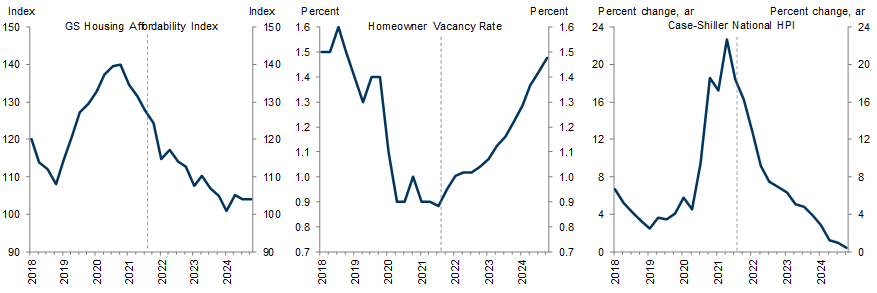

The supply-demand picture that has been the basis for our call for a multi-year boom in home prices remains intact. Housing inventories remain historically tight, while homes remain relatively affordable despite the recent price increases, and surveys of home buying intentions remain at healthy levels. Our model now projects that home prices will grow a further 16% by the end of 2022.

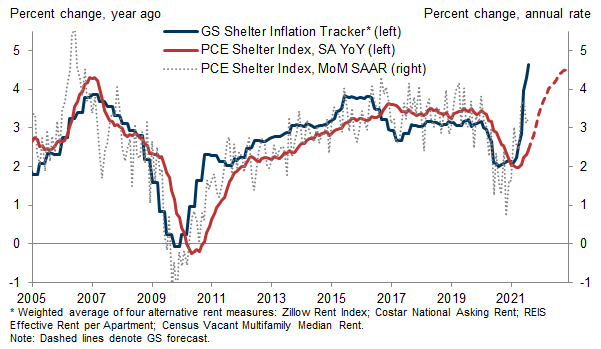

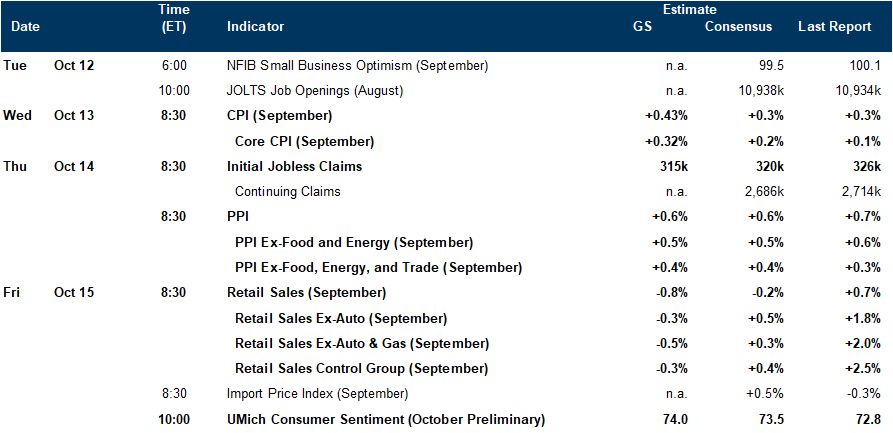

Does the sharp rise in home prices suggest an even faster acceleration in shelter inflation than our aggressive standing forecast of 4.5% at end-2022? The risks do now look more two-sided, especially with our shelter inflation tracker—a leading indicator based on several alternative rent measures—having jumped from 2.1% to 4.6% in just 6 months. But we caution that the most extreme increases reported in some alternative rent measures provide a misleading signal about the official data because they focus on units that turn over, where base effects from depressed rents in 2020 are stronger and government rent restrictions are weaker.

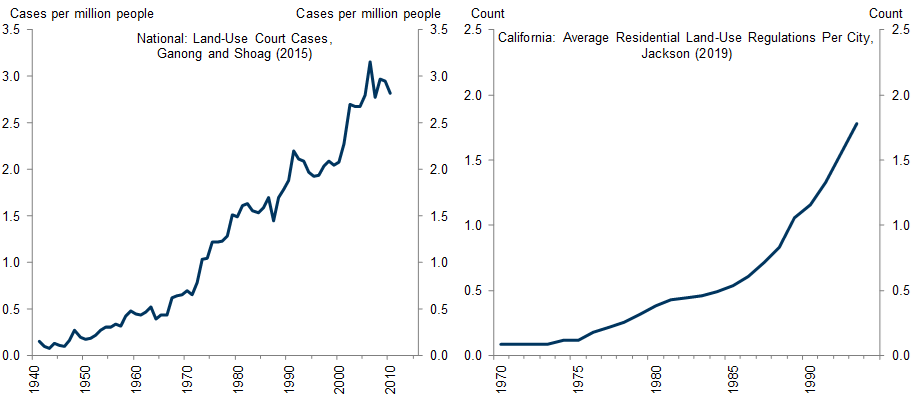

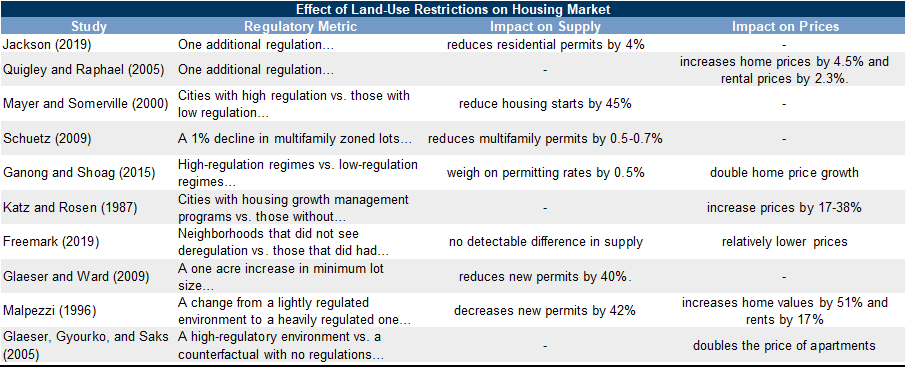

Is there a solution to the national housing shortage? Economic research shows that relaxing the zoning rules and other regulatory constraints that have impeded homebuilding for decades would boost supply and lower prices and rents. But in practice, this has been difficult politically.

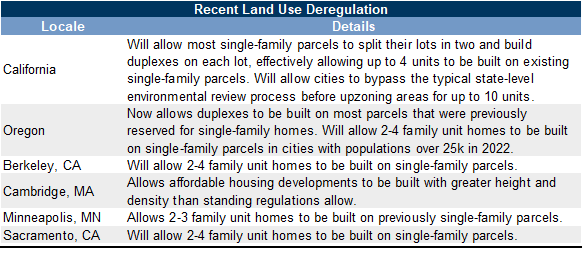

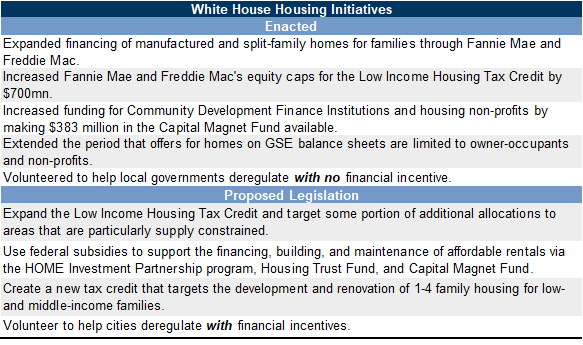

Some state and local governments are pushing to substantially reduce regulatory constraints. Most notably, California recently abolished single-family zoning statewide. The White House hopes to use housing funding to incentivize others to follow suit, but much of the proposed $400bn in housing-related grants and tax subsidies is likely to be cut from the reconciliation bill. As a result, nationwide changes seem unlikely for now, and limited state and local changes are only a partial step toward relieving the housing shortage.

The Housing Shortage: Prices, Rents, and Deregulation

Home Prices: A Higher Peak, But a Shorter Boom

How High Will Rent Inflation Rise?

Is There a Solution to the National Housing Shortage?

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ Ben Metcalf, David Garcia, Ian Carlton, and Kate Macfarlane, “Will Allowing Duplexes and Lot Splits on Parcels Zoned for Single-Family Create New Homes?” 2021.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.