The recent news on highly-levered Chinese property developers running into liquidity problems, and the latest data showing sharply falling land transactions and property sales on the back of regulatory tightening, exacerbate investors’ long-held concerns over China housing. In this note, we examine both the fundamental demand and credit supply aspects of the Chinese housing market.

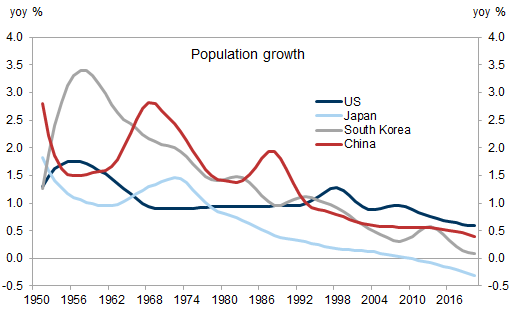

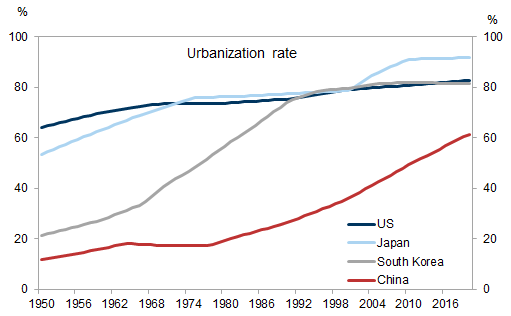

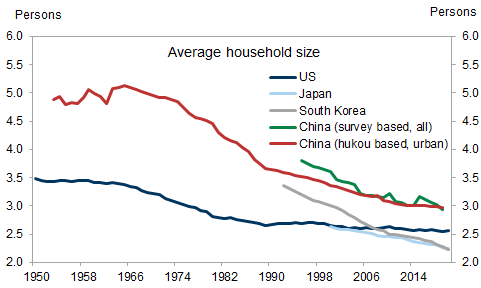

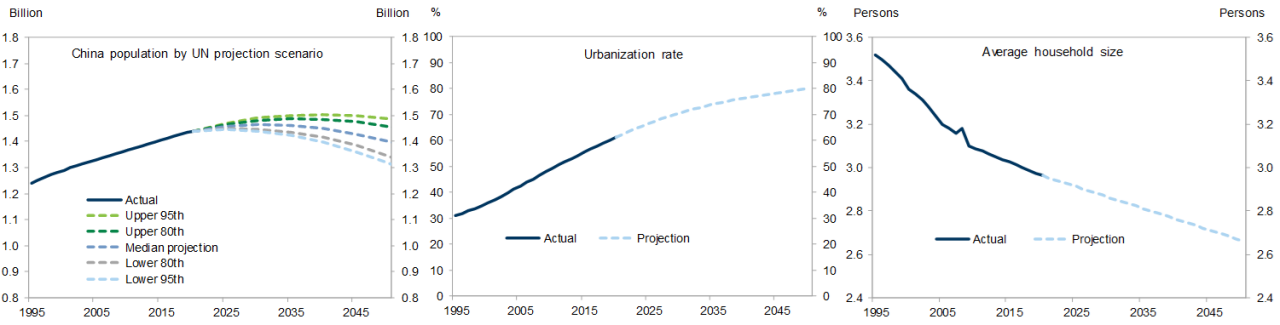

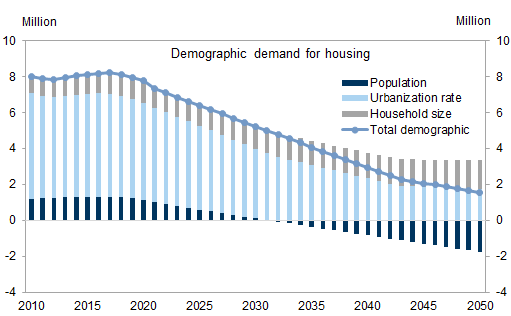

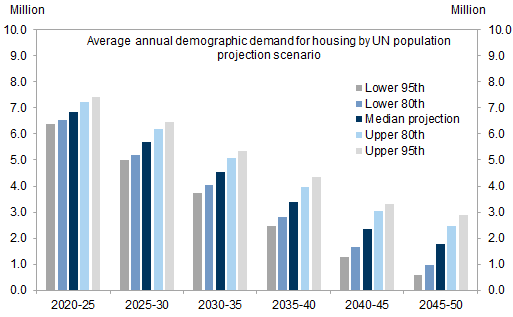

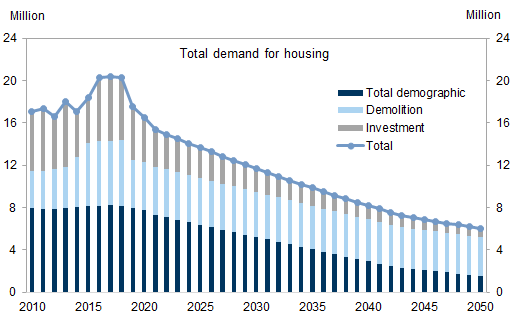

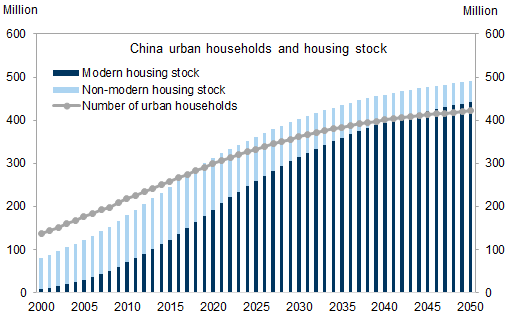

On housing demand, we estimate demographic, replacement and investment demand separately. Demographic demand in turn is decomposed into total population, urbanization rate, and average household size. By our estimates, annual demographic demand may decline from 8mn units in the 2010s to only 1.5mn by 2050 on falling population and fading support from urbanization, partly offset by slightly smaller average family size.

Given China’s still large stock of non-modern housing in urban areas, replacement demand is likely to remain significant for years to come. We expect annual demolitions to drop only gradually from 4.5mn units now to about 3.5mn by 2050. Investment demand is poised to shrink in the coming years as household expectations adjust to the new policy regime of “housing is for living in, not for speculation”. However, investment demand is unlikely to disappear entirely because of the high household saving rate and limited investment options. We expect a steady fall in investment demand from 3.5mn units pa now to 2mn in 2030 and less than 1mn by 2050.

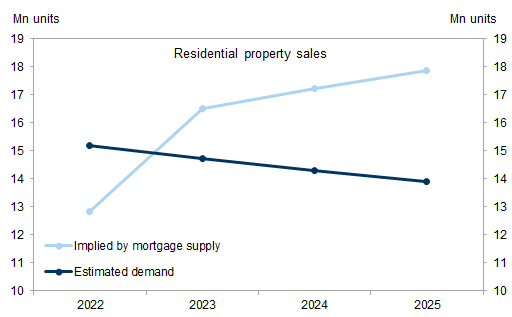

Adding up the various pieces, we believe total demand for urban housing has peaked in China and may fall from 18mn pa in the 2010s to 6mn by 2050. Because many of the underlying drivers such as demographics tend to move slowly, we expect a gradual fall in annual new demand: around -5% in 2022 and -3% pa thereafter.

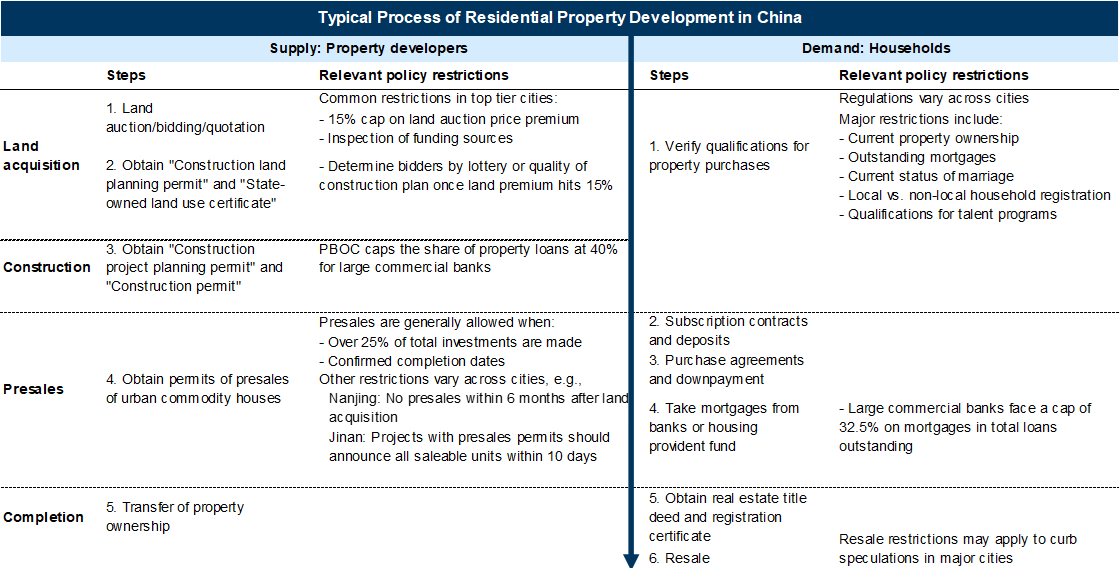

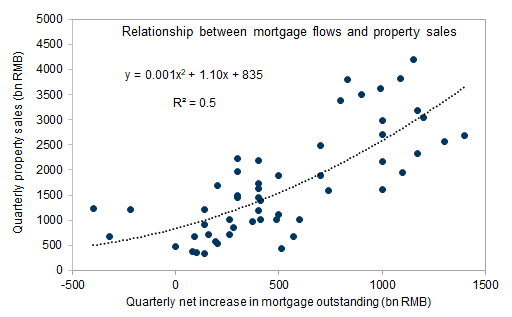

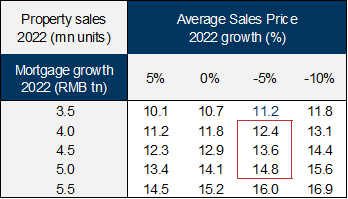

However, policy-driven credit tightening could have a dramatic effect on property sales in the near term. Using the mortgage cap policy as an example and building on our banks analysts’ estimates, we calculate that property sales may drop as much as 20% next year if banks were to meet the mortgage cap target by end-2022. This is why we believe credit supply holds the key to China's housing outlook in the near term while demand holds the key in the long run.

Credit supply holds the key to China housing outlook in 2022

Waning demographic demand for housing

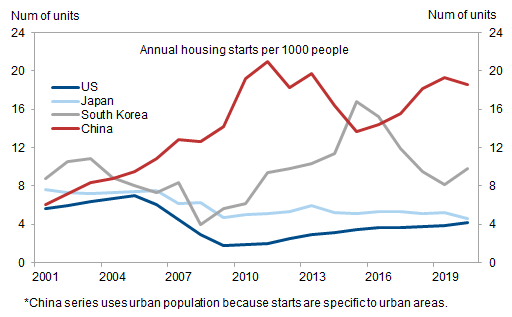

Exhibit 1: China appears to be building significantly more residential housing units per capita than other countries

Exhibit 2: Population growth has been declining in China

Exhibit 6: Household formation may decline from 8mn per year in 2010s to 1.5mn in 2050

Exhibit 7: Household formation would be 0.5mn lower per year in 2020-25 under the more bearish UN population projection

Replacement demand an important driver for years to come

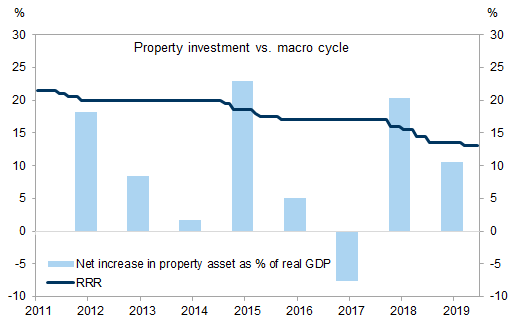

Investment demand with Chinese characteristics

Exhibit 8: Households increased property investment during economic downturns historically

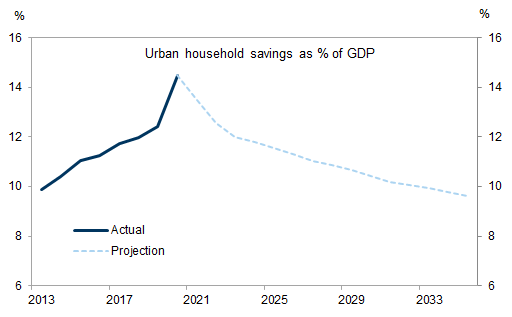

Exhibit 9: Urban household savings likely on downtrend, but still high in the coming decade

Adding up the total demand

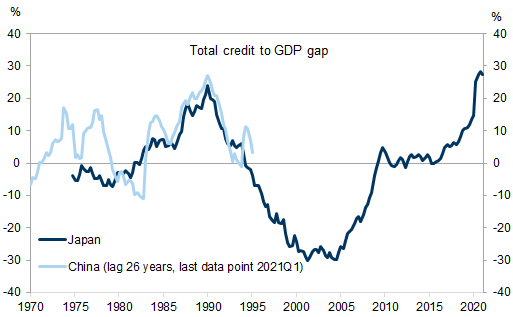

Credit tightening in the property market

Exhibit 13: A strong correlation between mortgage growth and property sales

Exhibit 14: Number of property sales that mortgage lending can finance under different house price assumptions

Exhibit 15: Mortgage supply is likely to constrain property sales next year under the mortgage cap regulation

Exhibit 16: Japan’s housing bust was arguably triggered by tightening banks’ real estate lending

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.