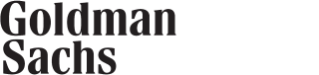

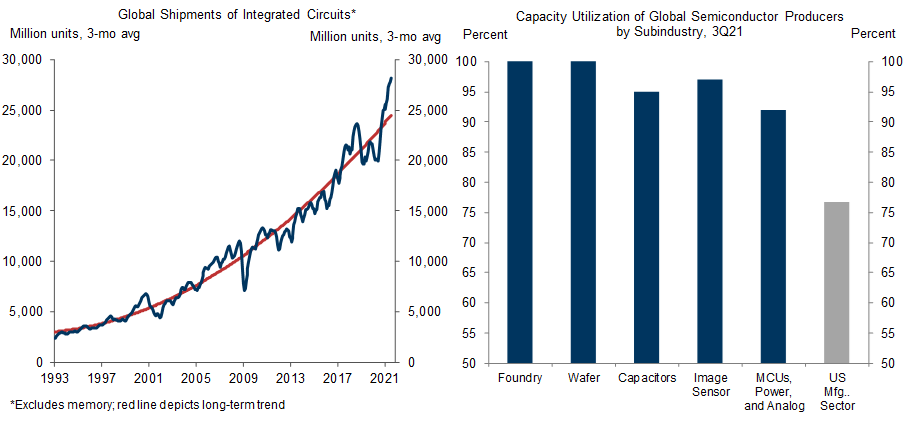

With used car prices rising sharply again and 30+ million tons of cargo waiting outside US ports ahead of the holiday season, we assess three key drivers of supply chain normalization and their most likely timing: 1) improved chip supply driven by post-Delta factory restarts (4Q21) and eventually by expanded production capacity (2H22 and 2023); 2) improved US labor supply (4Q21 and 1H22); and 3) the wind-down of US port congestion (2H22).

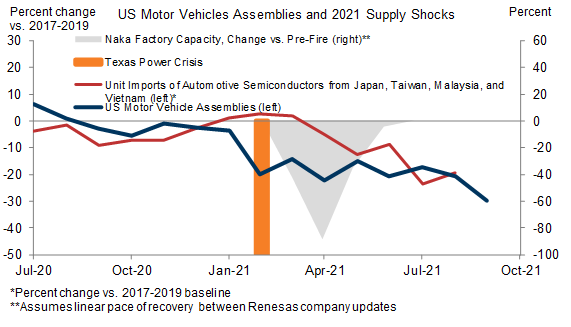

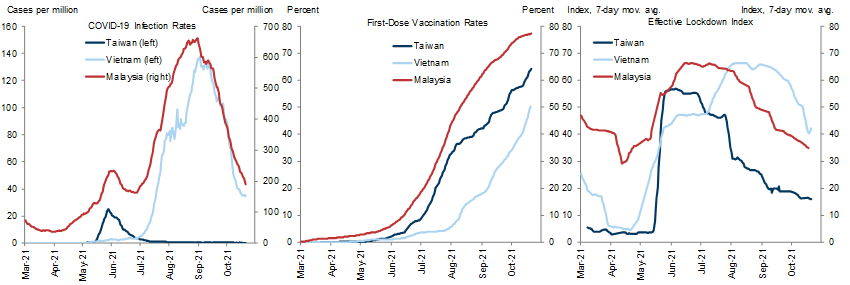

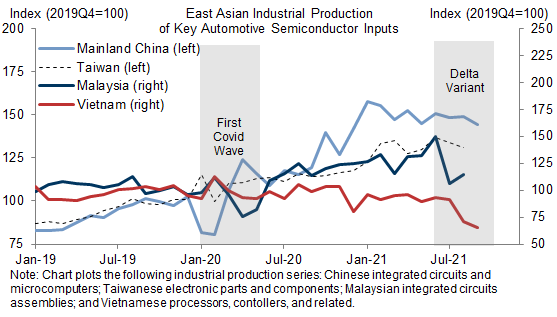

The first channel for easing supply constraints and core goods inflation is a post-Delta rebound in Southeast Asian chip production. Imports of key semiconductor inputs from Malaysia and Vietnam had declined 36% by August due to covid lockdowns, leading to a 15% monthly drop in US auto production in September (to 71% of the 2019 level). But rapid vaccination has already led to reduced infections and partial relaxation of lockdowns, which should improve automotive chip supply and US vehicle production in Q4.

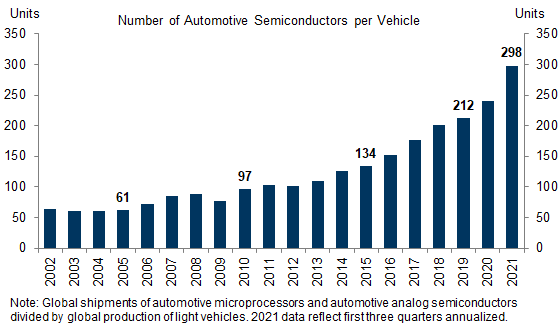

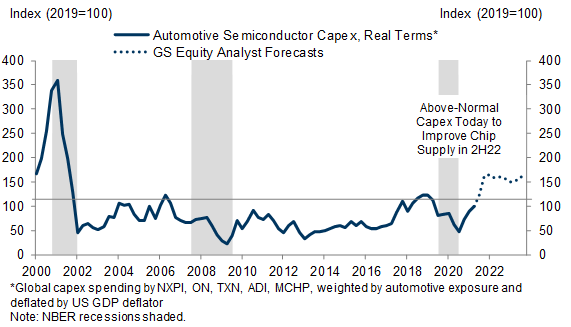

While this could return US auto production to late 2020 levels, a buildout of microchip production capacity is probably required to sustain above-normal production, restock heavily depleted vehicle inventories, and keep up with the rising semiconductor requirements of smart cars. This is likely to take longer, and we now expect auto dealer inventories to remain very low through mid-2022.

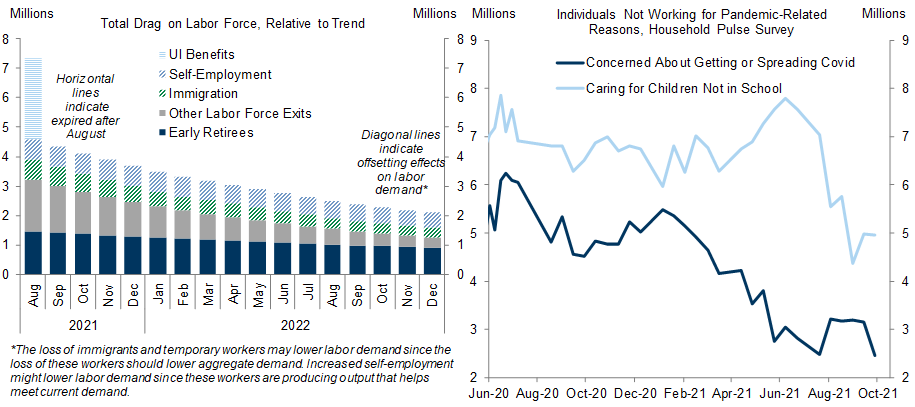

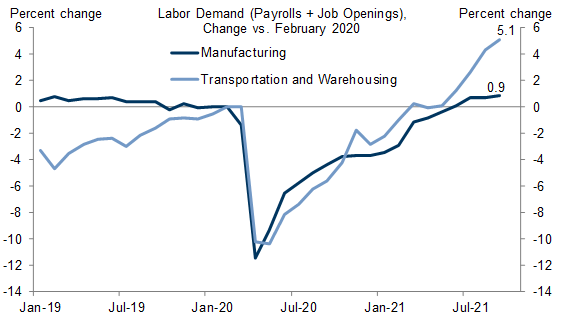

The second channel for easing supply constraints is improving labor supply. We estimate the September expiration of emergency unemployment insurance benefits will boost Q4 job growth by around 1mn, and we expect some of the 2-3mn individuals staying away from the workplace because of health concerns to return to the job market by mid-2022.

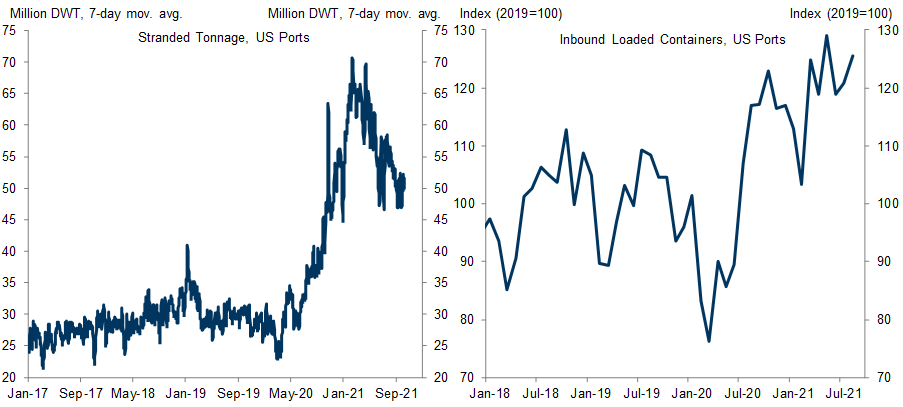

The third channel for easing supply constraints is reducing port congestion after the busy US holiday and pre-Chinese New Year shipping windows. A quicker flow of imports would help to alleviate shortages and reduce inflationary pressures for items such as furniture and sporting goods.

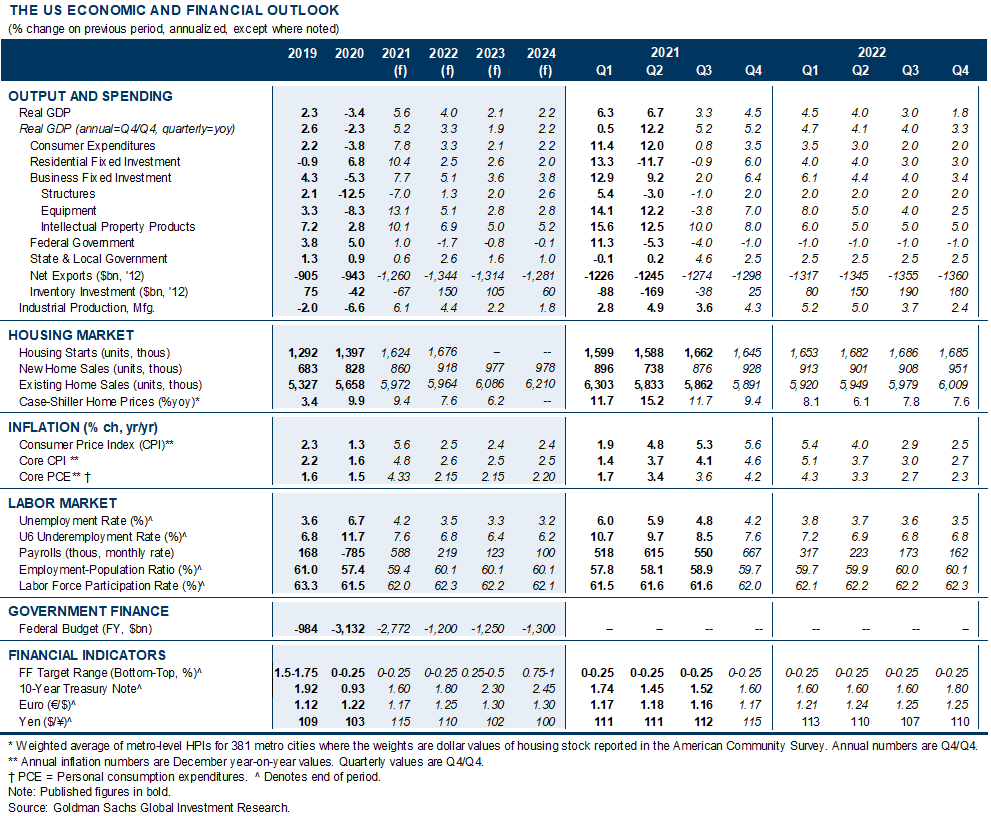

We are boosting our sequential inflation assumptions for Q4 and early 2022. We now expect year-on-year core PCE inflation of 4.3% at year-end, 3.0% in June 2022, and 2.15% in December 2022 (vs. 4.25%, 2.7% and 2.0% previously). This slower resolution of supply constraints means that year-on-year inflation will be higher in the immediate aftermath of tapering than we had previously expected. While we expect inflation to be on a sharp downward trajectory at that point and to continue falling through end-2022, this higher-for-longer path increases the risk of an earlier hike in 2022.

Track My Package: A Roadmap for Supply Chain Normalization

Channel 1, Step 1: Improved Chip Supply from East Asia Reboot

GS Effective Lockdown Indices (ELI)—particularly in Malaysia, Vietnam, Mainland China, and Taiwan

East Asian industrial production and exports of semiconductors, electrical components, and consumer electronics

Automaker commentary on near-term chip availability

China industrial policy, with respect to power cuts and the Delta variant

Early- and mid-month trade reports (Japan, Taiwan, and Korea)

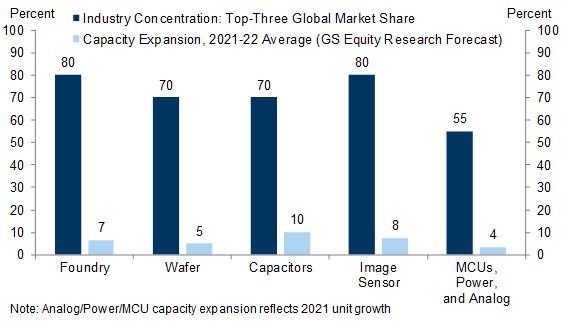

Channel 1, Step 2: Improved Chip Supply from New Capacity

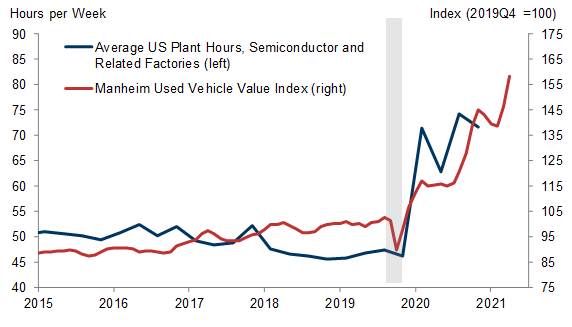

Global semiconductor shipments, particularly automotive: Microcontroller Units (MCUs), power semiconductor, analog devices

GS equity research forecasts for semiconductor capacity growth

2022 auto production forecasts (GS equity research, IHS)

US industrial production of computers, communication equipment, and semiconductors

Foreign production and US imports of auto and consumer electronics

Channel 2: Improved US Labor Supply

Payrolls, particularly manufacturing and transportation

JOLTS, particularly manufacturing and transportation

Industrial production of consumer goods, excluding autos and high tech

Supplier deliveries components of ISMs and regional Fed surveys

Labor force participation rate

Channel 3: Unwind of Port Congestion

Transportation payrolls, particularly in the marine cargo handling, support activities for transportation, couriers and messengers, and warehousing and storage sectors

Ships at anchor and inbound container traffic at US ports

Shipments component of the Cass Freight Index

US ex-auto manufacturing production

US imports of cars and consumer goods

Real retail inventories, excluding autos

Inflation and Fed Implications

Spencer Hill

- 1 ^ Measurement is a challenge in understanding the semiconductor shortage and tracking its resolution, because imports and shipments data are collected in nominal terms, and the deflators used do not convert them into discrete units (which in many cases are a binding constraint on unit auto or smartphone production).

- 2 ^ For example, the automotive chip expansion announced by Intel in March is not expected to commence deliveries this year.

- 3 ^ Labor supply is currently lagging demand, as hours worked in the transportation sector are up only 1.3% and hours worked in manufacturing are down relative to pre-pandemic levels.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.