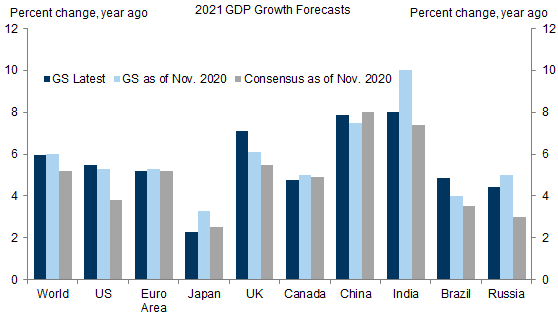

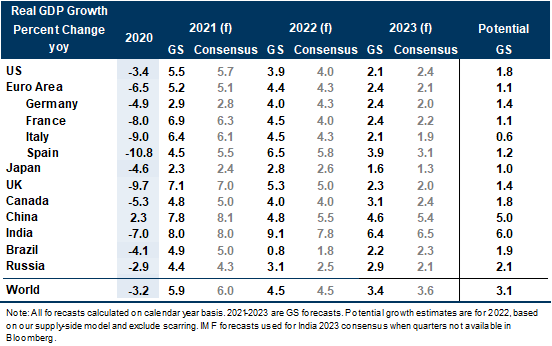

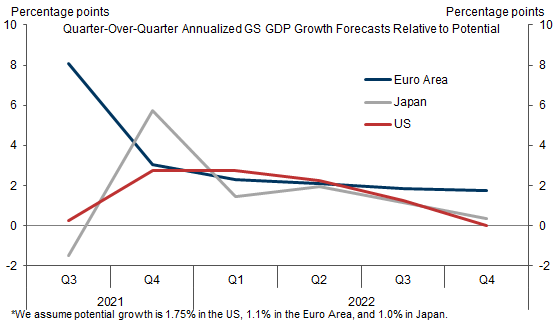

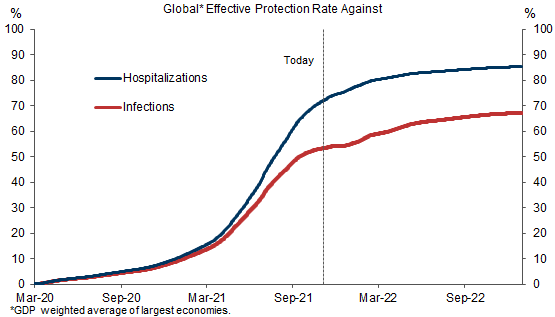

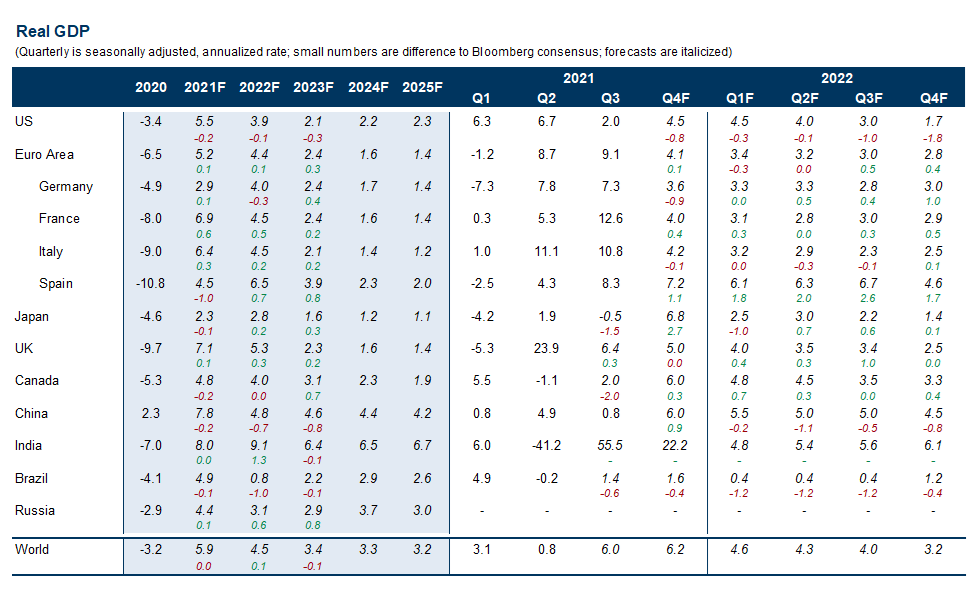

Although the fastest pace of recovery now lies behind us, we expect strong global growth in coming quarters, thanks to continued medical improvements, a consumption boost from pent-up saving, and inventory rebuilding. For 2022 as a whole, global GDP is likely to rise 4½%, more than 1pp above potential.

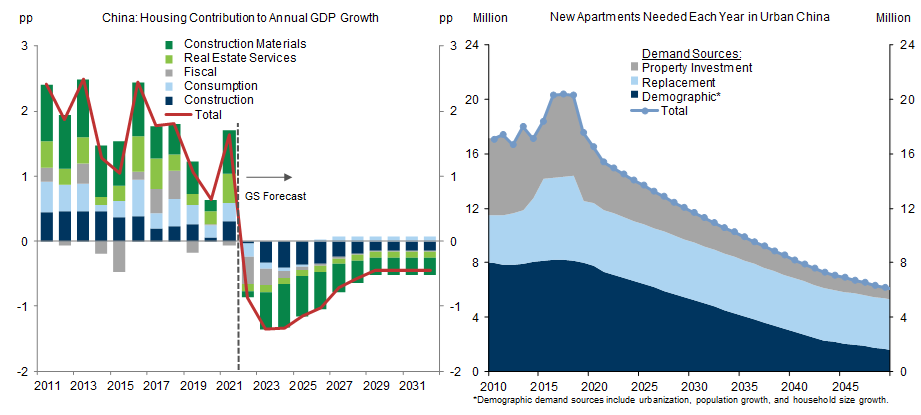

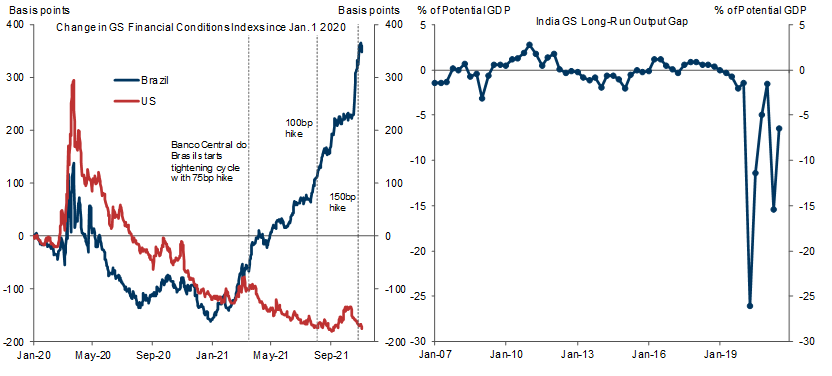

The major DM economies should grow rapidly through midyear and then moderate gradually as the near-term impulses wane. In EM, we expect comparatively sluggish performance in China, where the property market is likely to soften further and macro policy looks set to ease only modestly, and in Brazil, where financial conditions have tightened sharply and a potentially messy election looms. By contrast, we are more optimistic on India because of significant catch-up potential and on Russia because of a boost from the oil and gas sector.

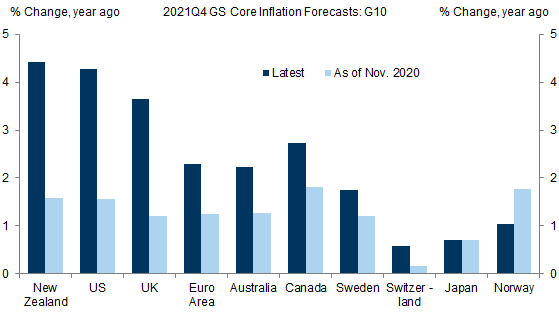

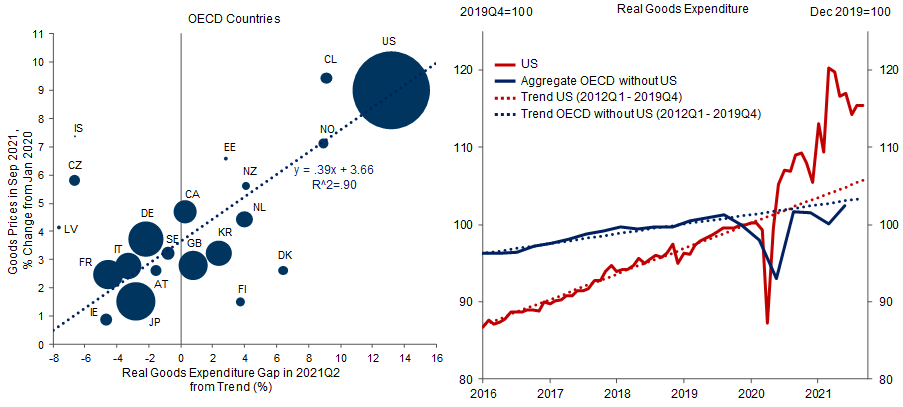

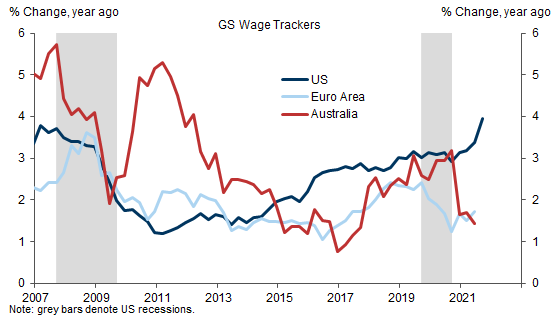

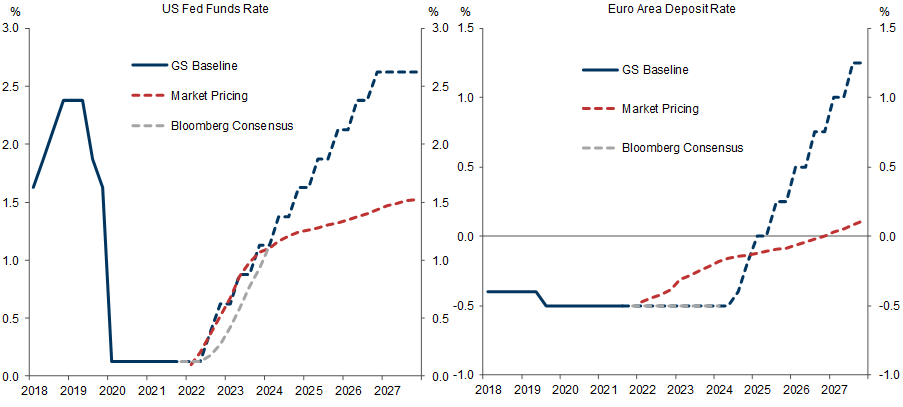

The biggest surprise of 2021 has been the goods-led inflation surge. This recently prompted us to pull forward our forecast for Fed liftoff by a full year to July 2022. Subsequently, we expect a funds rate hike every six months, a relatively gradual pace that assumes a normalization in goods prices and in overall inflation (albeit later and more partial than we previously thought).

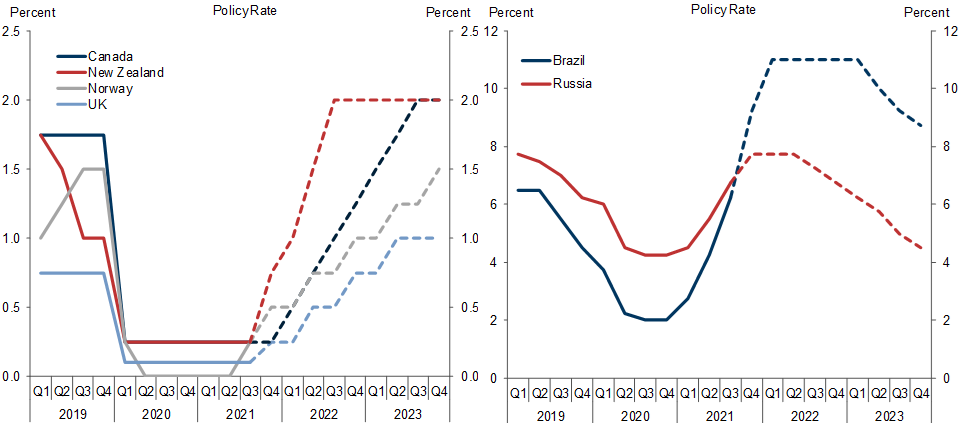

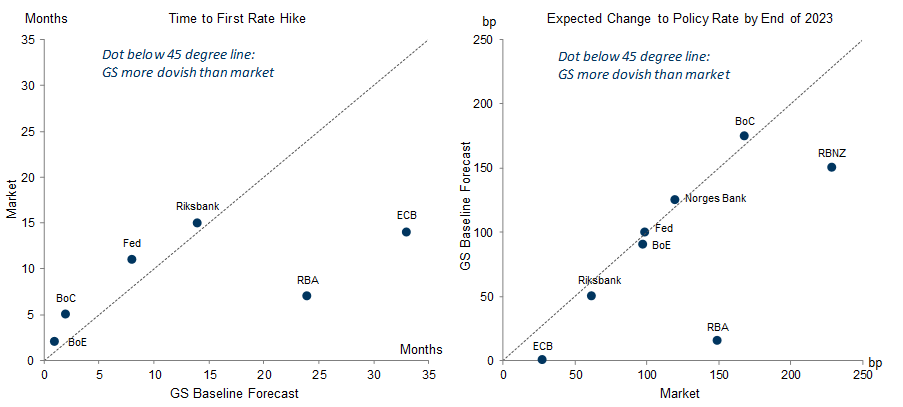

By the time Fed hikes get underway, some advanced economies (including the UK and Canada) should be well into the interest rate normalization process, and a number of economies in Latin America and Eastern Europe may already be approaching its end. By contrast, we think the ECB and RBA are still far away from hiking rates, and markets seem to have overshot in their expectation of an imminent hawkish turn.

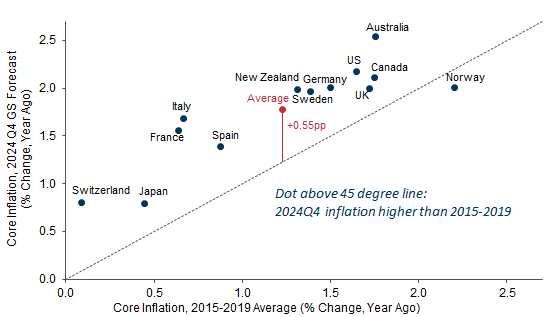

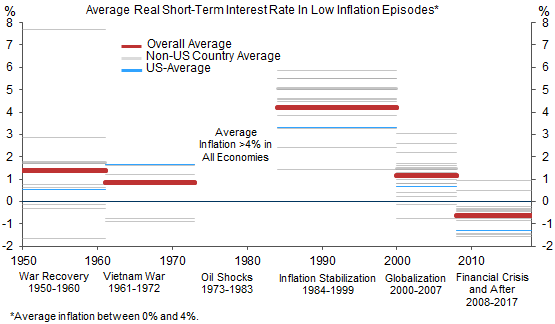

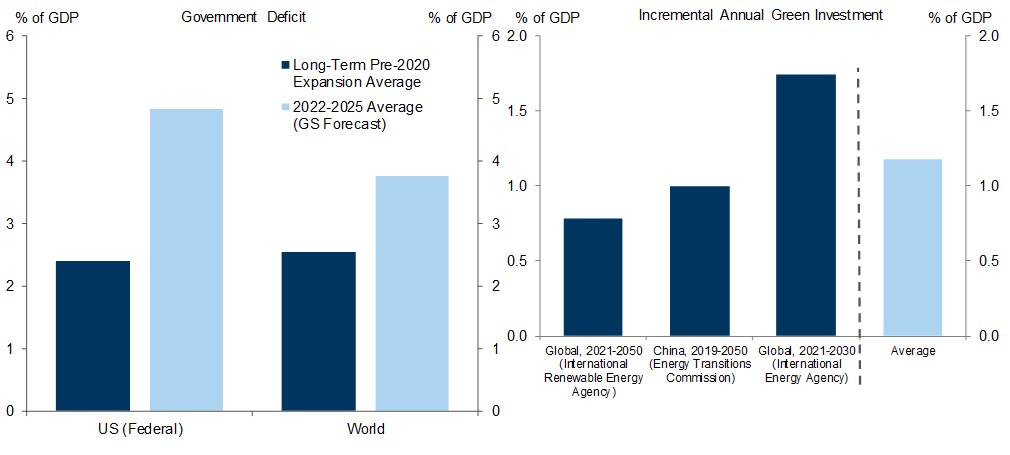

Beyond the next few years, we expect nominal policy rates across most DM economies to rise well beyond the rock-bottom levels now priced in the bond market. For one thing, inflation should settle ½pp above the pre-pandemic level on average, in part because central banks have tweaked their goals accordingly. Moreover, neutral real rates are more likely to rise than to fall, given increased political tolerance for budget deficits and climate-related investment needs.

GS Macro Outlook 2022: The Long Road to Higher Rates

Another Strong Year Coming

Exhibit 4: Further Medical Improvements

Higher Inflation, Earlier Liftoff

Exhibit 7: Inflation Has Been Much Higher Than Expected in Most G10 Economies

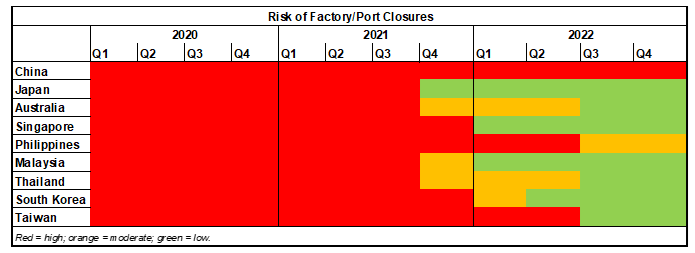

Exhibit 9: Diminishing Risk of New Covid-Driven Shocks From Asia to Global Goods Supply

Central Bank Leaders and Laggards

A Long Way From Nominal Neutral

Exhibit 14: G10 Inflation Should Settle ½pp Above the Pre-Pandemic Level on Average

From Pandemic Risks to Inflation Risks

- 1 ^ We calculate this rate as the population share with some immunity from vaccination or prior infection, multiplied by the strength of the protection against each outcome

- 2 ^ The Pfizer results were particularly strong. In the initial topline readout, the drug reduced hospitalizations by 89% relative to the control group, and there were zero deaths in the treatment group versus seven (or 1.8%) in the control group.

- 3 ^ See Alain Durré, Sören Radde, Filippo Taddei, "Persistent Fiscal Support for the European Recovery," European Economics Analyst, 24 October 2021.

- 4 ^ See Daan Struyven, Dan Milo, "Fiscal Come, Fiscal Go", Global Economics Analyst, 24 August 2021.

- 5 ^ See Hui Shan, "Credit Supply Holds the Key to China Housing Outlook in 2022", Asia Economics Analyst, 11 October 2021.

- 6 ^ See Spencer Hill, "Track My Package: A Roadmap for Supply Chain Normalization", US Economics Analyst, 26 October 2021.

- 7 ^ See Joseph Briggs, "Will Worker Shortages Be Short-Lived?", US Economics Analyst, 4 October 2021.

- 8 ^ We estimate substantial amount of excess slack, with a 2021Q3 long-run output gap of -5% for the Euro area average, and even -10% for Spain. See, Daan Struyven, Sid Bhushan, Dan Milo, Yulia Zhestkova, Jan Hatzius, "Tight Now, Slack Later", Global Economics Analyst, 15 October 2021.

- 9 ^ See, Jan Hatzius, Daan Struyven, "Later but Steeper in the Post-Pandemic Economy", Global Economics Analyst, 31 May 2021.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.