While the unemployment rate continues to fall quickly, labor force participation has made no progress since August 2020. In this US Daily, we examine where labor force participation remains weak and potential explanations for its underperformance.

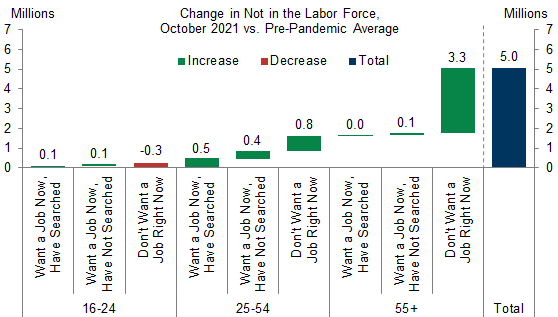

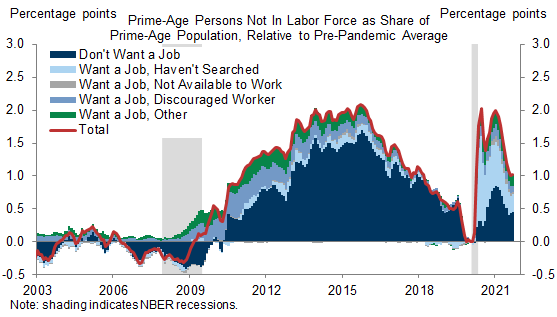

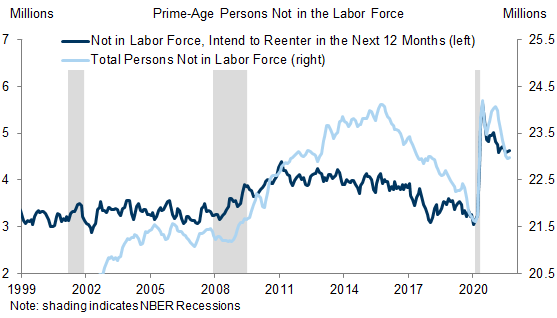

Most of the 5.0mn persons who have exited the labor force since the start of the pandemic are over age 55 (3.4mn), largely reflecting early (1.5mn) and natural (1mn) retirements that likely won’t reverse. The outlook for prime-age persons who have exited the labor force (1.7mn) is more positive, since very few are discouraged and most still view their exits as temporary.

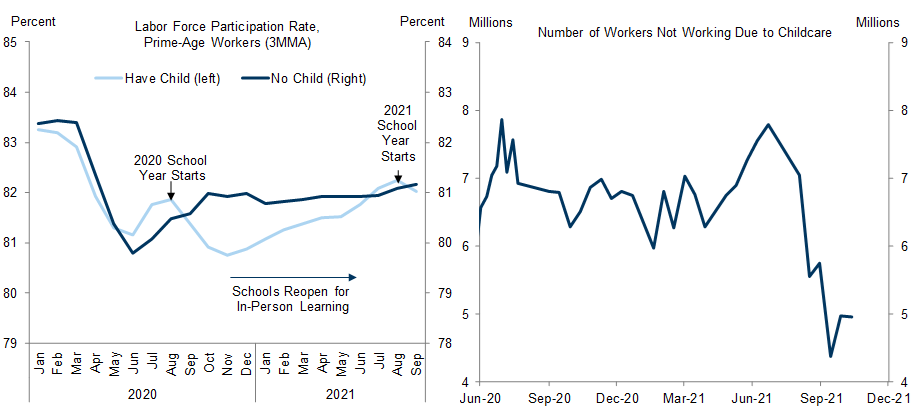

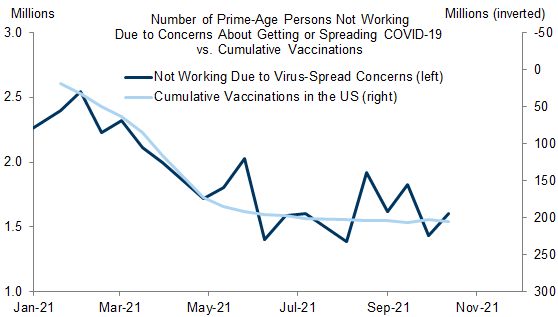

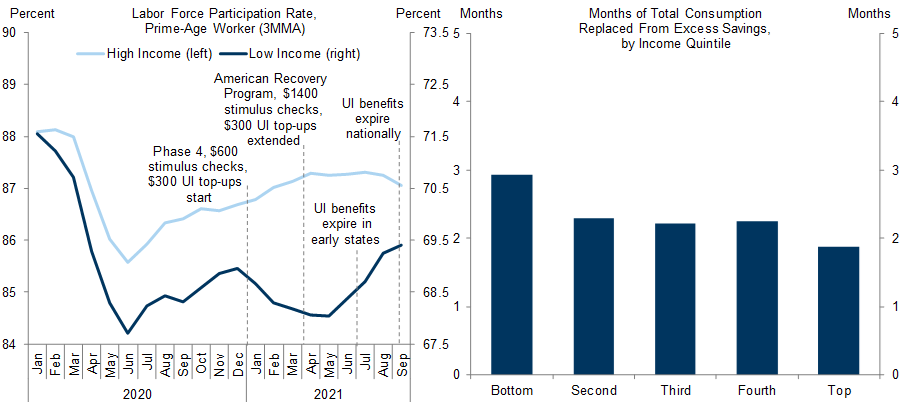

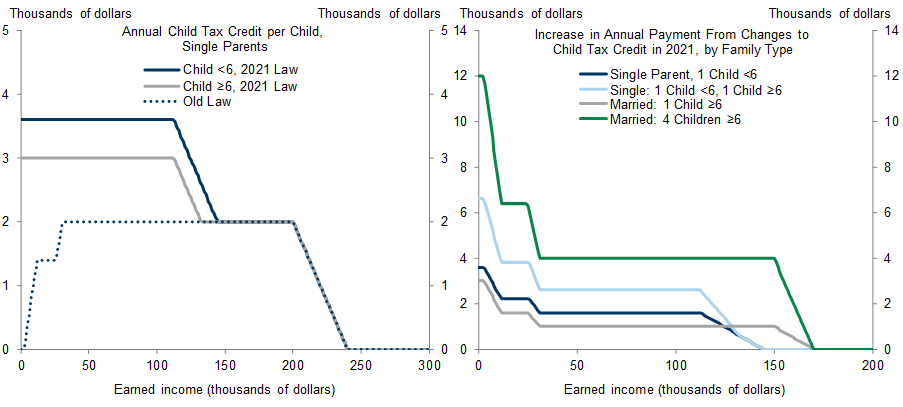

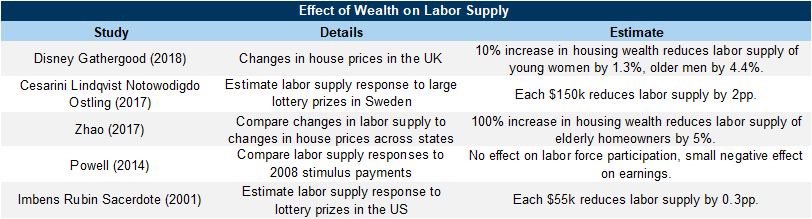

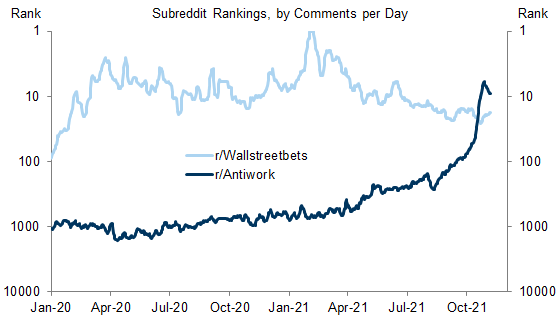

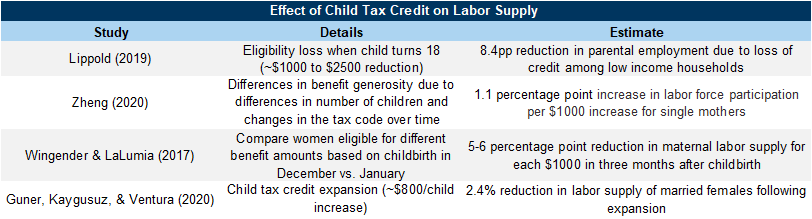

There are several reasons why workers have delayed labor force reentry. Childcare constraints and elevated fiscal transfers likely weighed on participation earlier in the pandemic but should have small effects going forward, and most households have only accumulated enough excess savings to postpone re-entry for a few months. Labor supply drags from Covid concerns appear sizeable and will likely linger in the medium-term, since it may take some time for some people to feel comfortable returning to work. We also see potential for longer-lasting drags due to wealth effects, and changing lifestyle and work preferences may prompt some workers to voluntarily remain out of the labor force for longer, provided they can afford to do so.

We continue to expect that the labor force participation rate will increase in the near-term, but we have nudged down our participation rate forecast to 1pp below trend at end-2021 (61.9%) and ½pp below trend at end-2022 (62.1%) following last Friday’s data. But because jobs are abundant and residual weakness in participation in mid-2022 will likely be due to changes in fiscal policy, wealth, and worker preferences, we expect that the FOMC will judge any participation shortfall that remains at that point to be structural or voluntary and will update their maximum employment goal accordingly.

Why Isn’t Labor Force Participation Recovering?

Joseph Briggs

Appendix

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.