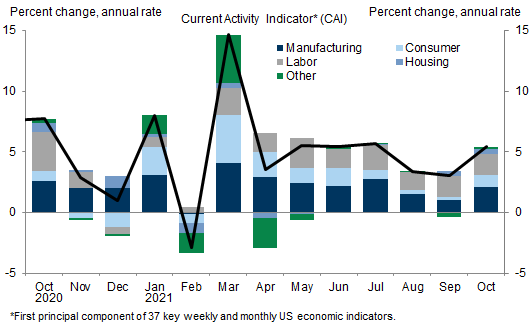

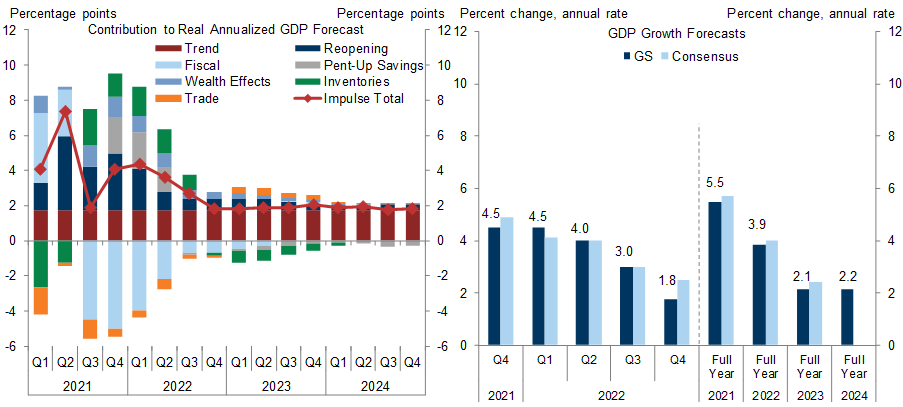

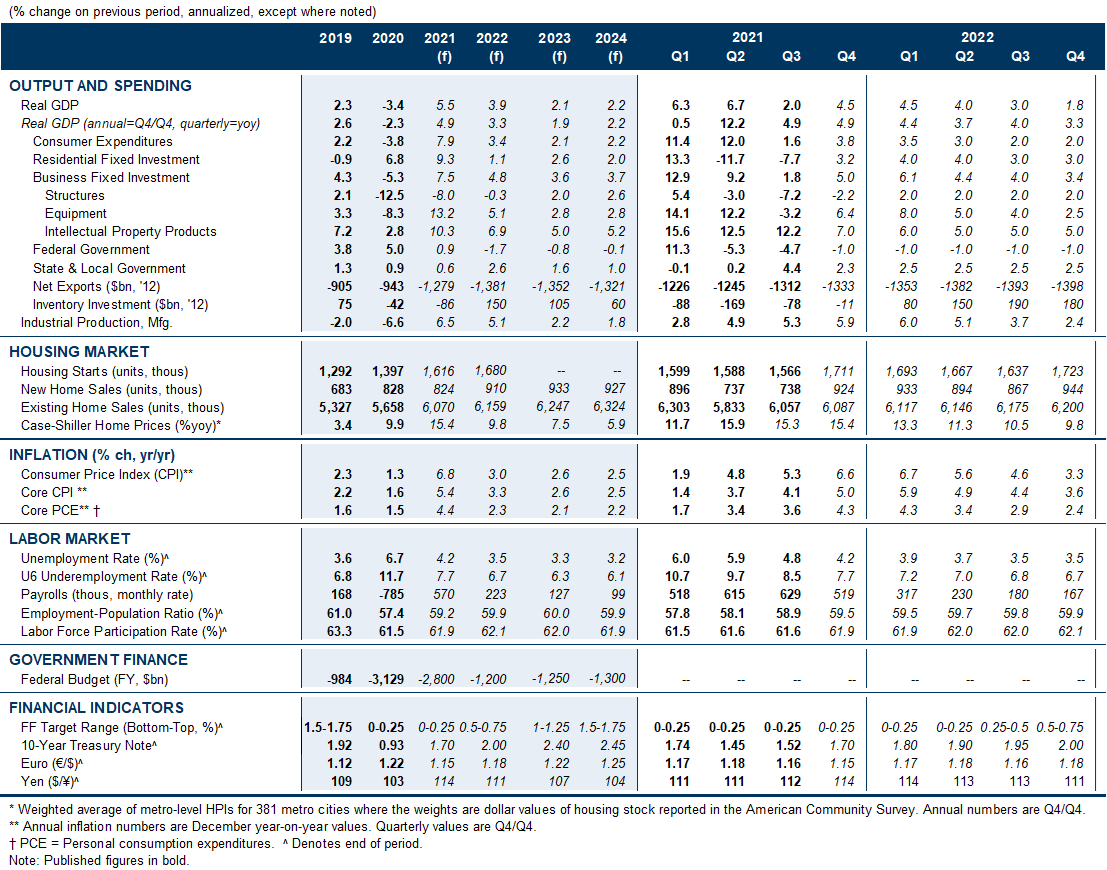

The US economy largely followed the rapid road to recovery that we expected this year and is on track to round out the recovery next year as most of the remaining effects of the pandemic fade. But this year also brought a major surprise: a surge in inflation that has already reached a 30-year high and still has further to go. Mainly for this reason, we recently pulled forward our forecast of the timing of the Fed’s first rate hike to July 2022, shortly after tapering ends.

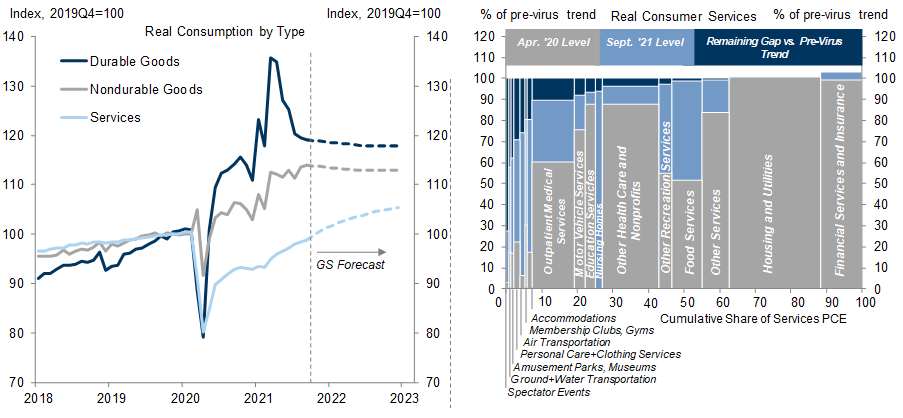

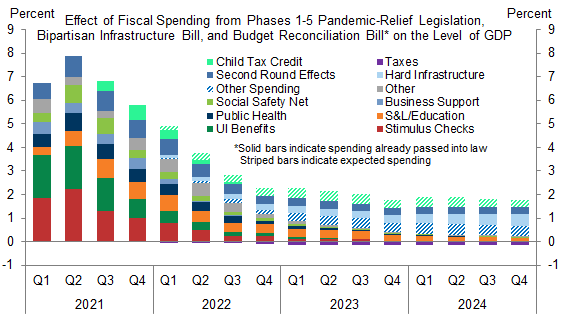

We expect the economy to reaccelerate to a 4%+ growth pace over the next few quarters as the service sector continues to reopen, consumers spend part of their pent-up savings, and inventory restocking gets underway. These forces will contend with a large and steady headwind from diminishing fiscal support that we expect will ultimately leave GDP growth near potential by late 2022.

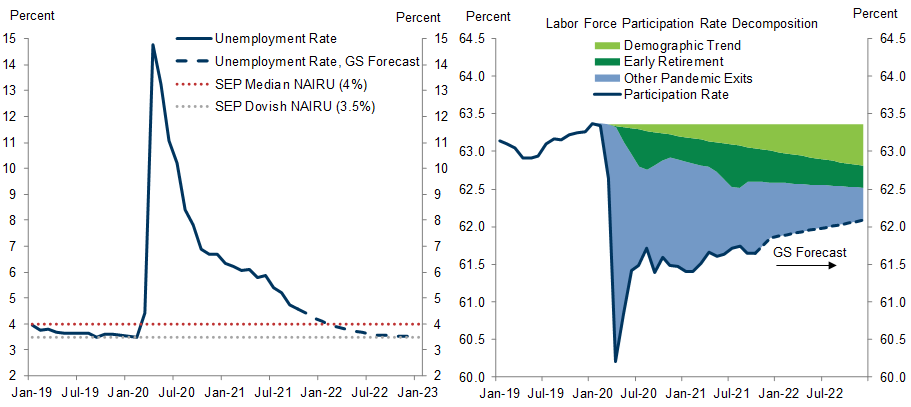

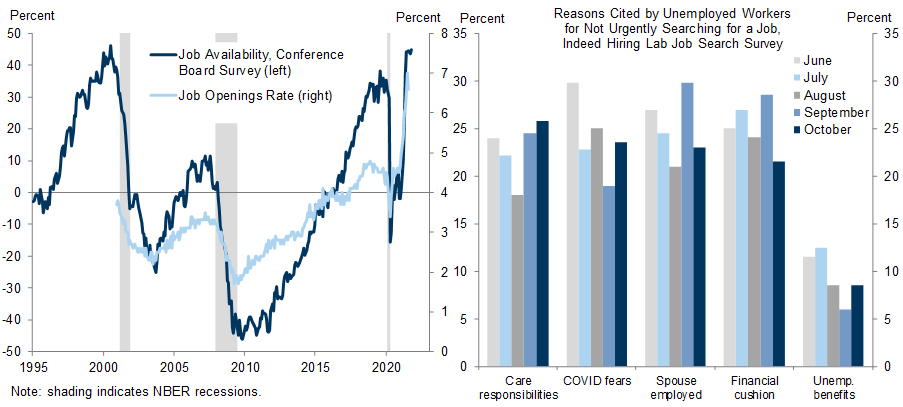

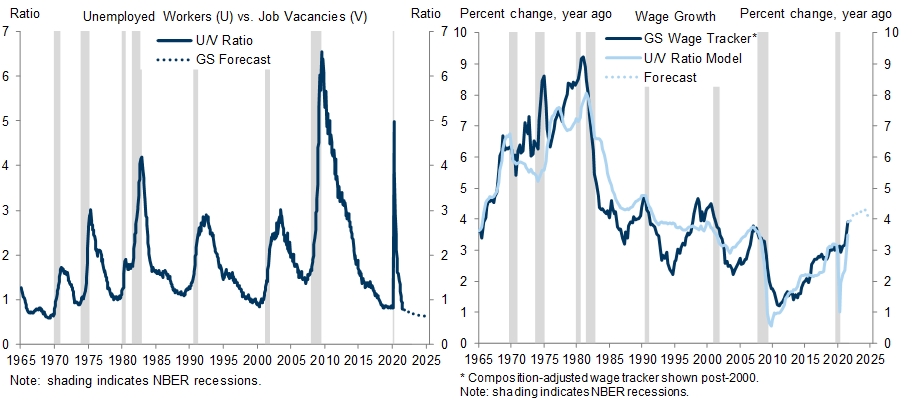

The labor market should reach maximum employment by the middle of next year as red-hot demand for workers and the end of enhanced unemployment benefits bring solid job gains. We expect the unemployment rate to reach 3.7% at mid-year and 3.5%—the pre-pandemic 50-year low—by end-2022. While labor force participation is likely to remain below its pre-pandemic trend, this looks structural or voluntary in an environment where job opportunities are plentiful.

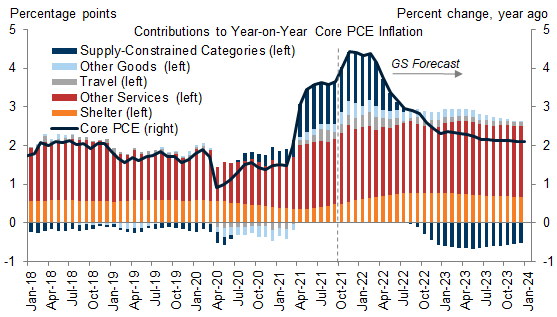

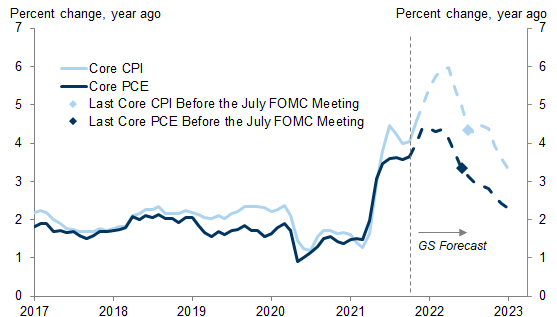

The inflation overshoot has been startling, but so far is attributable to a surge in durable goods prices driven by surprisingly severe and persistent supply-demand imbalances. We do expect persistent inflationary pressure from faster growth of wages and rents, but only enough to keep inflation moderately above 2%, in line with the Fed’s goal under its new framework. The current inflation surge will get worse this winter before it gets better, but as supply-constrained categories shift from a transitory inflationary boost to a transitory deflationary drag, we expect core PCE inflation to fall from 4.4% at end-2021 to 2.3% at end-2022.

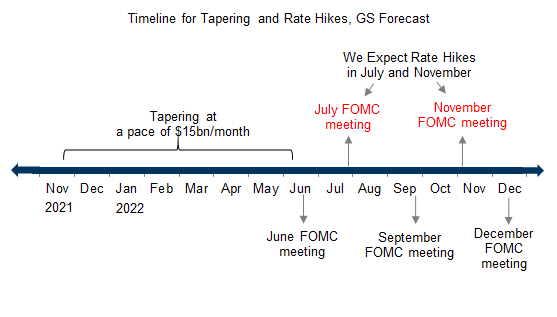

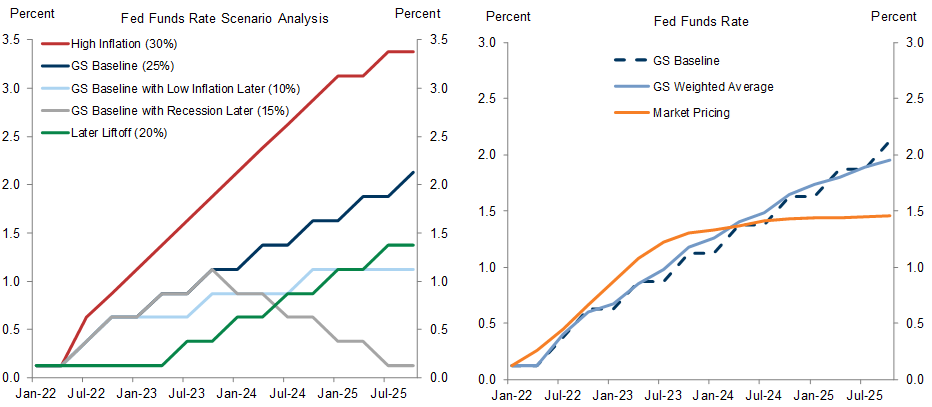

The FOMC is scheduled to complete the taper in mid-June 2022. Inflation will have run far above target for a while by then, and we think a seamless move from tapering to rate hikes will be the path of least resistance, with a first hike in July and a second in November. Because we expect growth and inflation to settle down by year-end without a need for aggressive monetary policy tightening, we have penciled in a slower pace of two hikes per year thereafter.

2022 US Economic Outlook: Early Liftoff

Rounding Out the Recovery

An Evolving View of Maximum Employment

Inflation Will Get Worse Before It Gets Better

From Tapering to Rate Hikes

David Mericle

- 1 ^ David Mericle and Jan Hatzius, “From Tapering to Rate Hikes,” US Economics Analyst, October 29, 2021.

- 2 ^ Ronnie Walker, “Consumer Spending: A Harder Path Ahead,” US Economics Analyst, September 6, 2021; “Coming to America: The Effect of Lifting Travel Restrictions on Spending and Employment,” US Daily, September 23, 2021.

- 3 ^ Joseph Briggs, “Updating Our Distributional Income and Spending of Pent-Up Savings Estimates,” US Daily, October 27, 2021; Joseph Briggs and David Mericle, “Pent-Up Savings and Post-Pandemic Spending,” US Economics Analyst, February 15, 2021.

- 4 ^ Spencer Hill, “Inventory Restocking and the Growth Outlook,” US Daily, July 28, 2021; Joseph Briggs, “The Capex Reset: New Investment for the New Work Environment,” US Economics Analyst, August 16, 2021.

- 5 ^ Alec Phillips, “Front-loaded Benefits, Clean Energy, and Corporate Tax Hikes,” US Daily, October 28, 2021.

- 6 ^ Joseph Briggs, “Updating Our Growth Impulses and GDP Forecast,” US Daily, October 10, 2021; Joseph Briggs and David Mericle, “Adding up the Growth Impulses: A Second Look,” US Economics Analyst, June 6, 2021.

- 7 ^ Joseph Briggs, “Estimating the Impact of Unemployment Insurance Benefit Expiration on Employment Using the August Microdata,” US Daily, September 16, 2021; Joseph Briggs and Ronnie Walker, “Back to Work When Benefits End,” US Economics Analyst, August 21, 2021.

- 8 ^ Joseph Briggs, “Why Isn’t Labor Force Participation Recovering?” US Daily, November 11, 2021.

- 9 ^ Spencer Hill, “How High Is Low-End Wage Growth?,” US Daily, September 20, 2021; David Mericle and Ronnie Walker, “Will Unemployment Benefit Expiration Slow Wage Growth? An Early Look from Ride-Hailing Services,” US Daily, August 13, 2021; David Mericle and Laura Nicolae, “The Inflation Risks from Stronger Low-End Wage Growth,” US Daily, June 30, 2021.

- 10 ^ Joseph Briggs, “Wage Growth Should Stabilize Around 4%, Consistent with the Fed’s Inflation Goal,” US Daily, November 3, 2021.

- 11 ^ David Mericle and Laura Nicolae, “The Inflation Risks That Matter for the Fed,” US Economics Analyst, May 16, 2021.

- 12 ^ Ronnie Walker, “The Housing Shortage: Prices, Rents, and Deregulation,” US Economics Analyst, October 11, 2021; Ronnie Walker, “Shelter Inflation and Booming House Prices,” US Daily, May 15, 2021.

- 13 ^ Ronnie Walker, US Monthly Inflation Monitor, October 29, 2021; Ronnie Walker, “Higher Business Inflation Expectations Are Mostly a Short-Term Signal,” US Daily, June 18, 2021.

- 14 ^ Spencer Hill and David Mericle, “2022 Inflation Outlook: Getting Worse Before It Gets Better,” US Economics Analyst, November 7, 2021.

- 15 ^ Spencer Hill, “Track My Package: A Roadmap for Supply Chain Normalization,” US Economics Analyst, October 26, 2021.

- 16 ^ Ronnie Walker, “The Growth and Inflation Consequences of Higher Energy Prices,” US Daily, October 19, 2021; Ronnie Walker, “The Commodities Boom and Consumer Prices,” US Economics Analyst, July 5, 2021.

- 17 ^ David Mericle and Spencer Hill, “US Daily: A Wider CPI-PCE Gap and a Hotter Inflation Dashboard in 2022,” US Daily, October 28, 2021.

- 18 ^ Joseph Briggs, Ronnie Walker, and Laura Nicolae, “The Fed’s Broad and Inclusive Maximum Employment Goal,” US Economics Analyst, March 22, 2021.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.