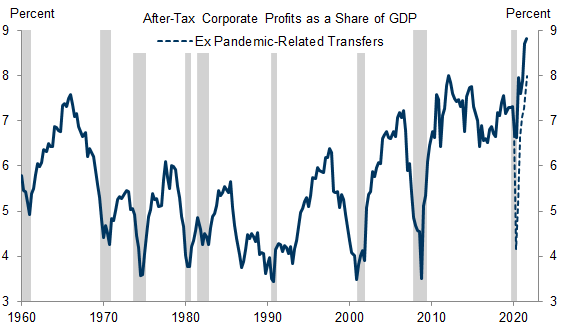

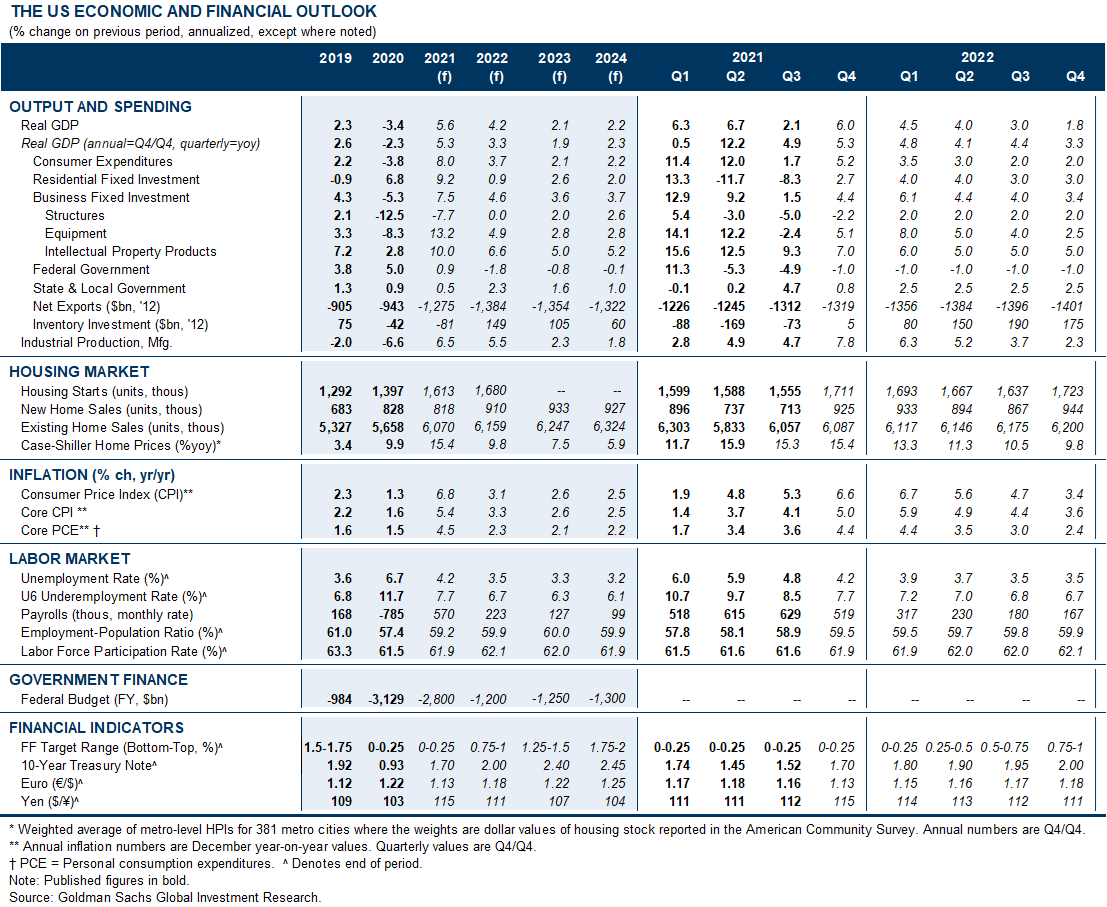

Labor and intermediate input costs have risen sharply in 2021, but so far businesses have been able to push through rising labor and input costs and preserve profit margins. In fact, national accounts profit margins reached an all-time high in 2021Q3, and remain at their second-highest level on record even after removing pandemic-related fiscal transfers. Whether profit margins will remain elevated will depend on whether companies can continue to pass higher costs through to prices, so in this US Economics Analyst we review the evidence regarding price pass-through from three sources of cost pressure.

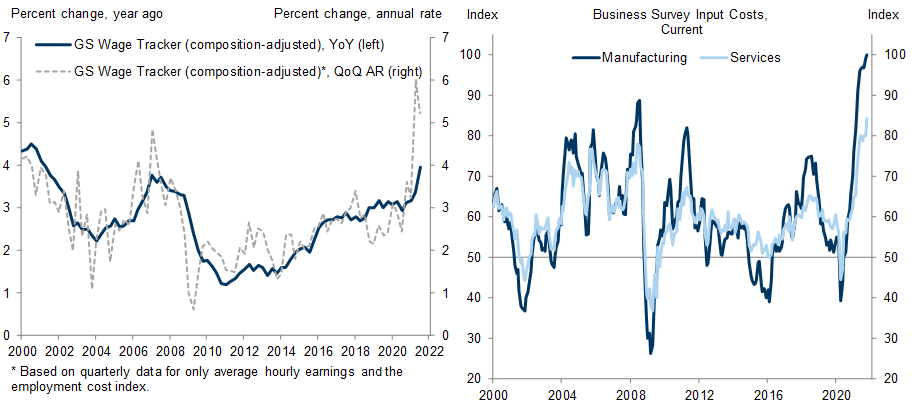

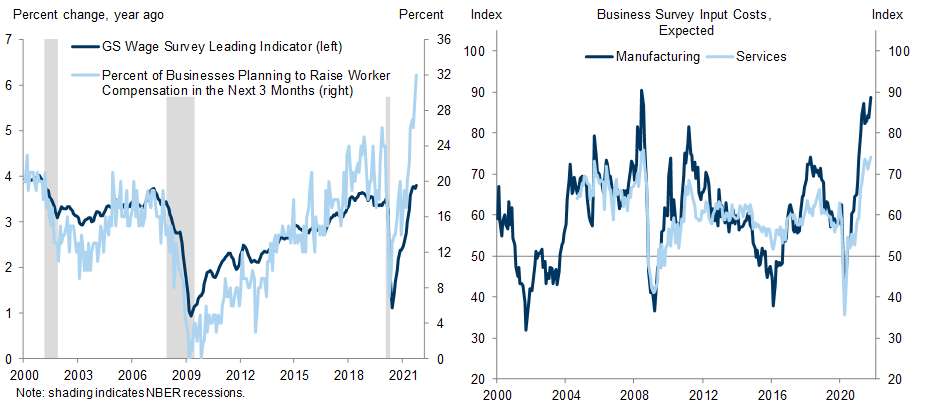

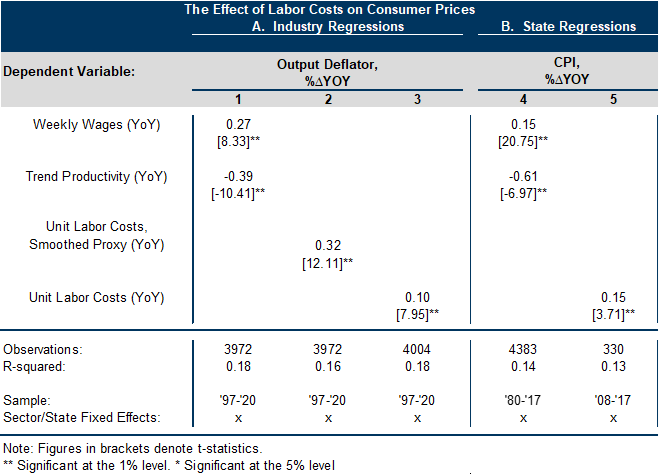

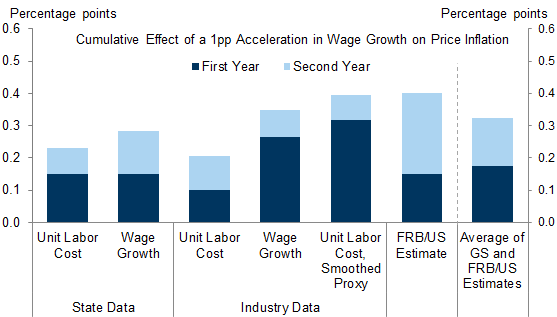

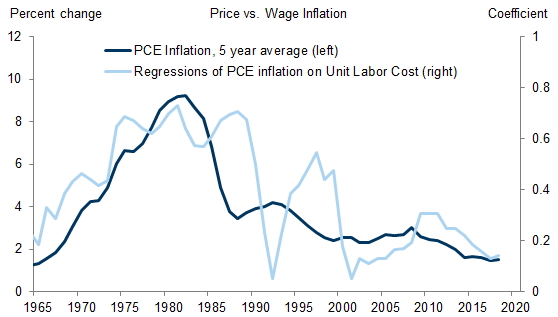

First, although rapid wage growth in 2021Q2-Q3 will likely slow as labor shortages ease, we expect that wage growth will remain firmer than at the end of last cycle and average a bit over 4% in 2022-2024. Using a set of industry- and state-level panel regressions, we estimate that a 1pp acceleration in wage growth boosts price inflation by about 35bps and lowers profit margins by about 20bps, although the pass-through rate likely varies over time.

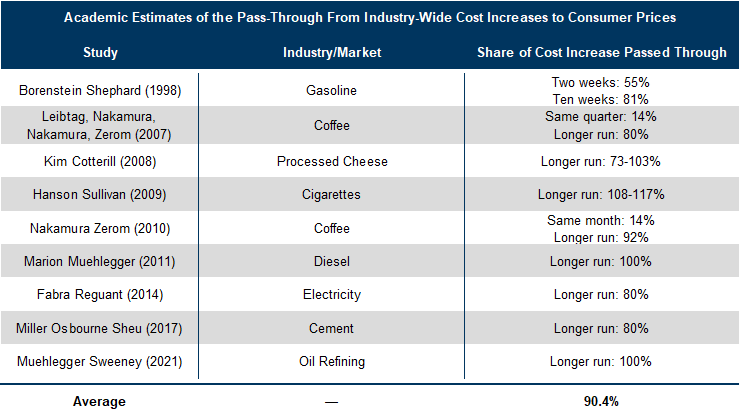

Second, upstream costs of intermediate goods and materials have also increased. We find that broad-based input cost increases have historically been mostly passed on to final prices. Rising costs of intermediate goods and materials will therefore likely continue to put upward pressure on consumer prices, but pose less of a threat to profit margins.

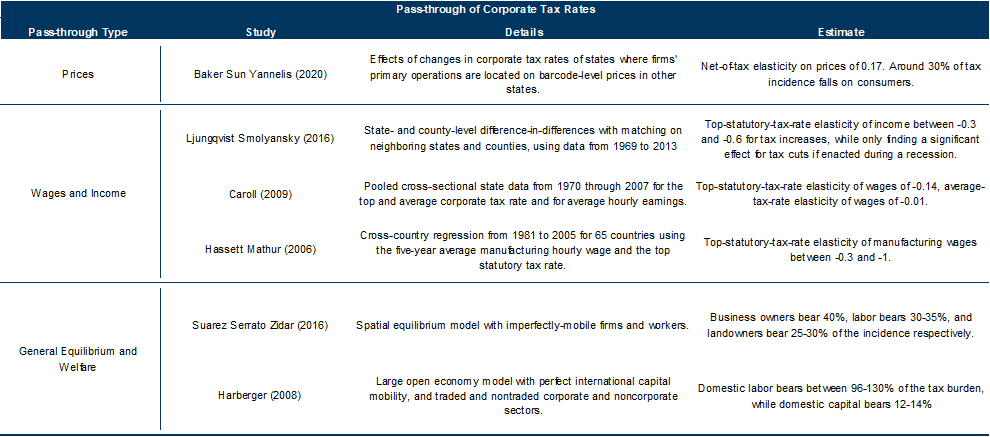

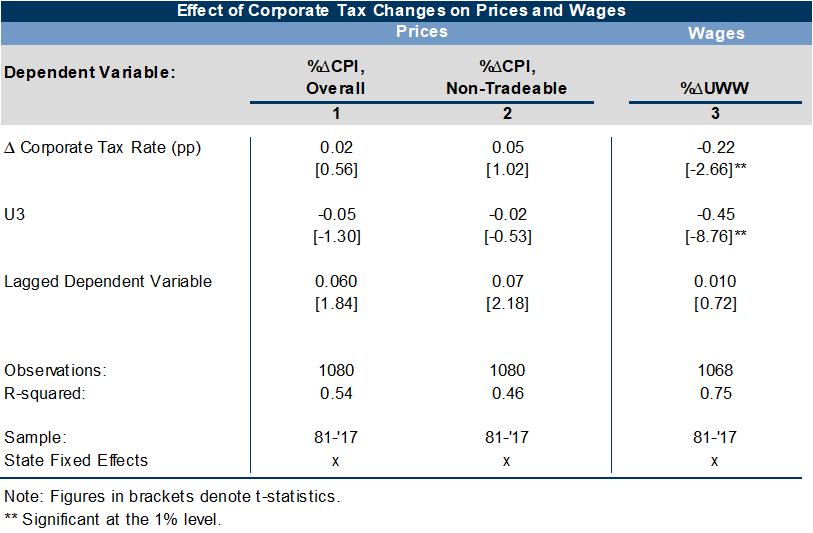

Third, the coming reconciliation bill will likely increase corporate taxes, and academic studies suggest that the incidence of corporate tax increases falls roughly evenly on consumers, workers, and businesses. We therefore expect modest inflation and margin pressures from corporate tax increases, although the ultimate effect will depend on the details of the upcoming legislation.

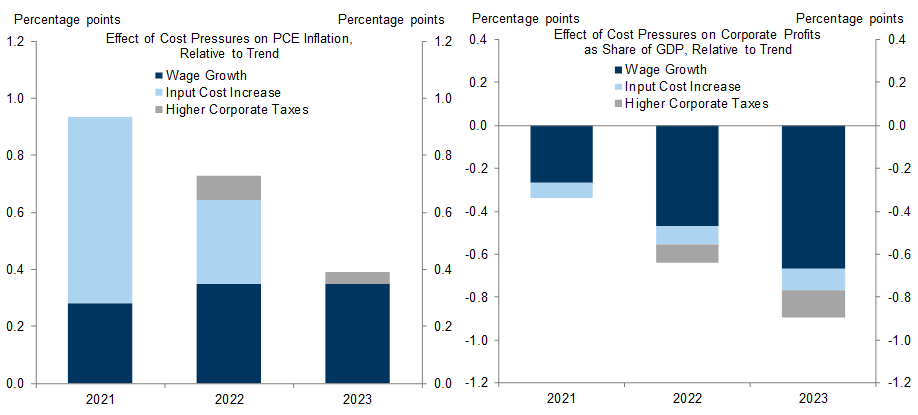

Based on our pass-through estimates, we expect that rising costs will boost price inflation in 2021 by around 0.9pp relative to trend, and that the inflationary pressure will ease sequentially to 0.7pp in 2022 and 0.4pp in 2023. Additionally, we estimate that cost pressures will lower national accounts profit margins by around 0.3pp in 2021, 0.6pp in 2022, and 0.9pp in 2023, with the hit to margins mostly reflecting higher labor costs, since most other cost increases will ultimately be passed through to consumers.

Who Pays for Input Cost Increases? Evaluating the Impact on Prices and Profit Margins

The Effect of Rising Labor Costs on Prices

The Effect of Intermediate Input Costs on Prices

The Incidence of Corporate Tax Increases

Adding Up the Effects on Prices and Margins

Joseph Briggs

- 1 ^ Hazell, J., Herreno, J., Nakamura, E. and Steinsson, J., 2020. The slope of the Phillips Curve: evidence from US states (No. w28005). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 2 ^ Baker, Scott R., Stephen Teng Sun, and Constantine Yannelis. “Corporate taxes and retail prices”. No. w27058. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

- 3 ^ Our price growth trend assumes 3% wage growth, 2% growth in intermediate input prices, and no change in corporate tax rates.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.