The emergence of the Omicron variant increases the risks and uncertainty around the US economic outlook. While many questions remain unanswered, we now think a moderate downside scenario where the virus spreads more quickly but immunity against severe disease is only slightly weakened is most likely. In this scenario, we see three main effects on the US economy.

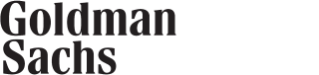

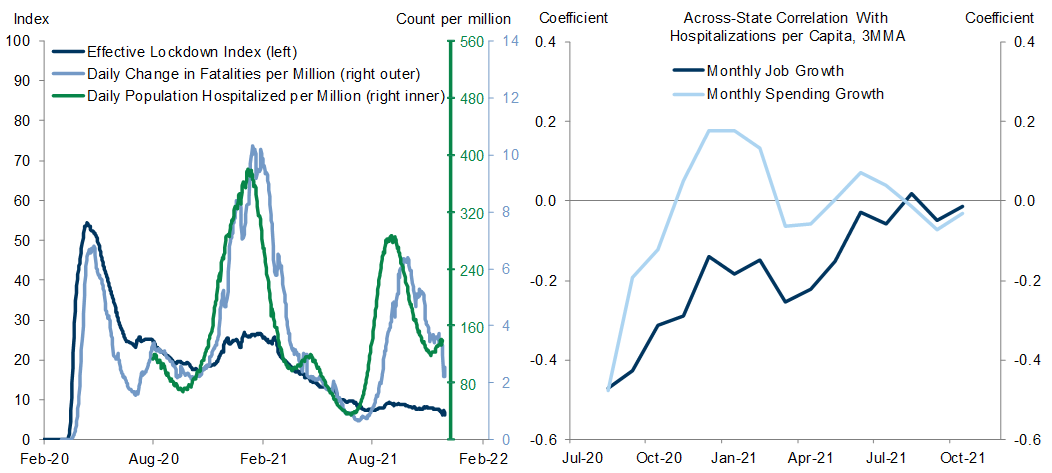

First, Omicron could slow economic reopening, but we expect only a modest drag on service spending because domestic virus-control policy and economic activity have become significantly less sensitive to virus spread.

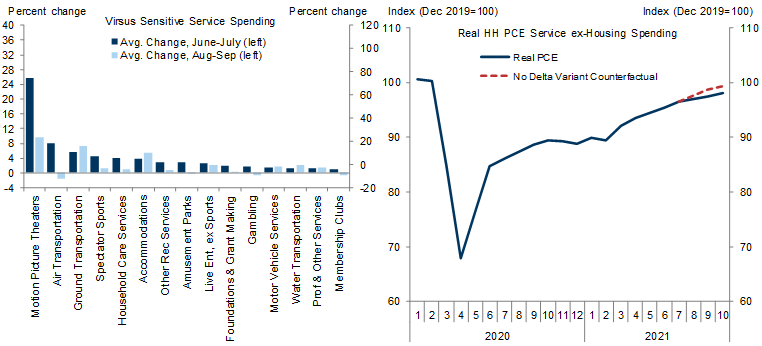

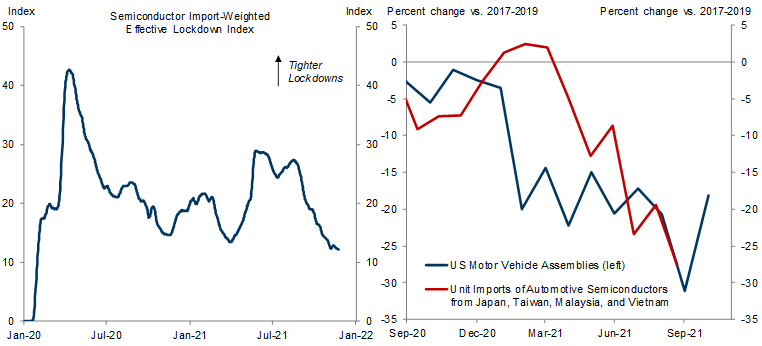

Second, Omicron could exacerbate goods supply shortages if virus spread in other countries necessitates tight restrictions. This was a major problem during the Delta wave, but increases in vaccination rates in foreign trade partners since then should limit the scope for severe supply disruptions.

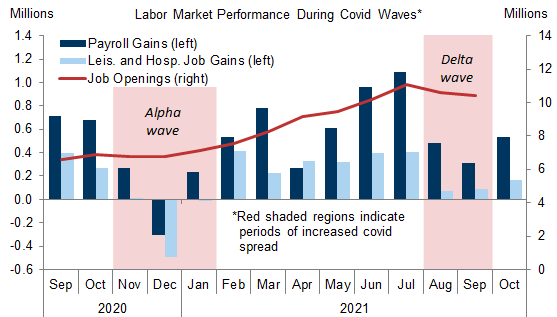

Third, Omicron could delay the timeline for some people feeling comfortable returning to work and cause worker shortages to linger somewhat longer.

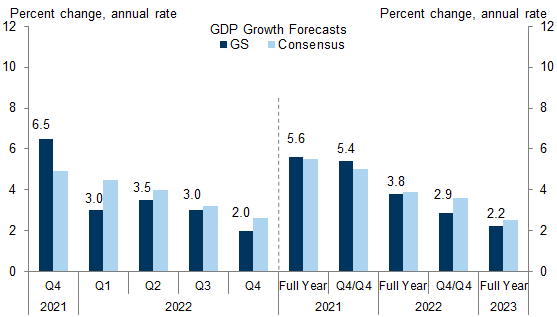

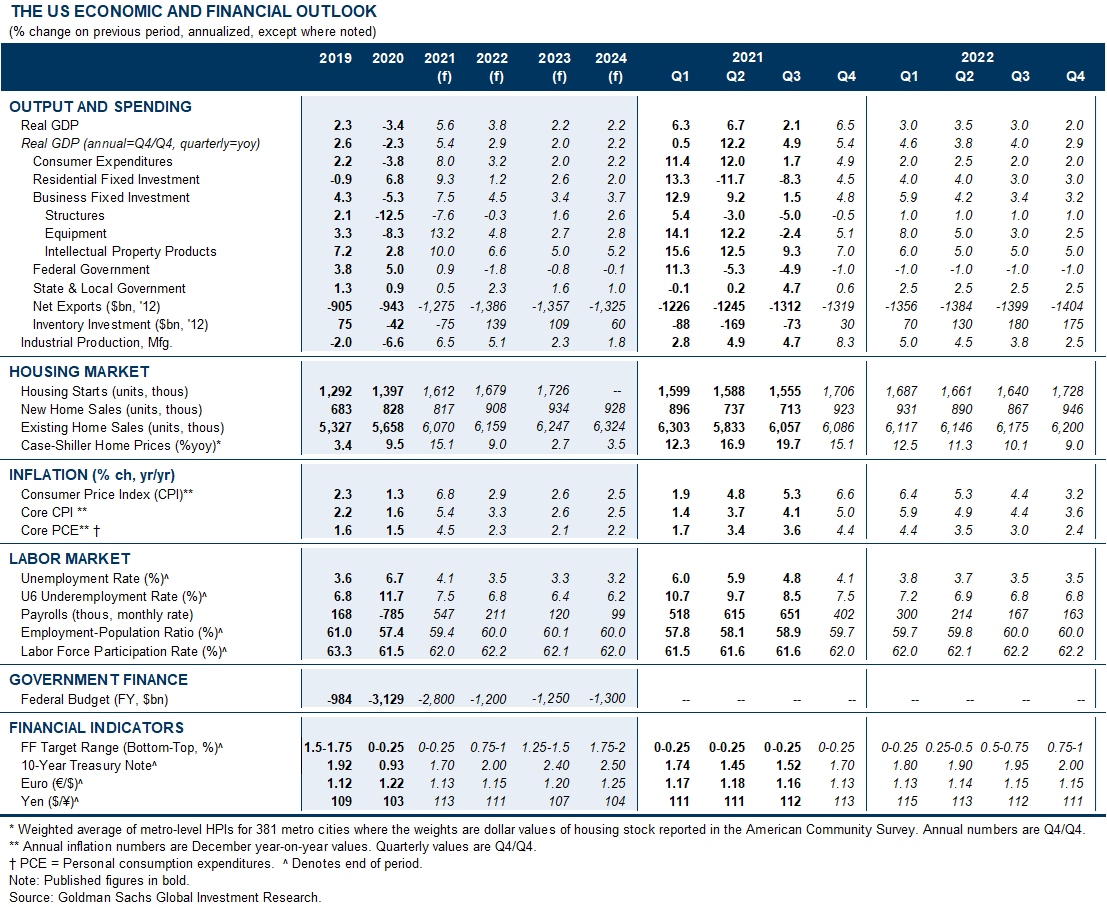

We have updated our GDP forecasts to incorporate our updated virus outlook as well as the latest GDP tracking data. These changes result in a +0.5pp (qoq ar) boost to our Q4 growth forecast based mostly on stronger inventory data, and a -1.5pp cut to growth in Q1 and -0.5pp cut in Q2 due to virus-related drags on reopening and goods supply. We now expect GDP growth of +6.5%/+3.0%/+3.5%/+3.0%/+2.0% in 2021Q4-2022Q4. This implies 2022 GDP growth of +3.8% (vs. 4.2% previously) on a full-year basis and +2.9% (vs. +3.3% previously) on a Q4/Q4 basis.

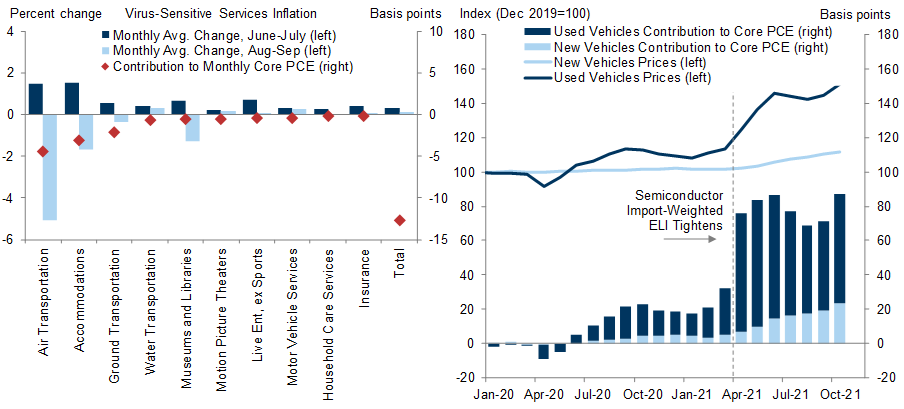

We see mixed implications for inflation. Reduced demand for virus-sensitive services such as travel could have a disinflationary impact in the near term, but prior virus waves suggest that such pressures would be temporary and reverse as demand recovers. In contrast, further supply chain disruptions due to Omicron or further delays in the recovery of labor supply could have a somewhat more lasting inflationary impact.

Updating Our Outlook to Incorporate Omicron

A Reopening Slowdown

A Delay in Supply Chain Normalization

A Slowdown in the Labor Market Recovery

Updating our GDP Forecasts

Risks to Inflation

Still on Track for a Faster Taper and an Early Liftoff

Joseph Briggs

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.