The Fed’s balance sheet normalization principles state that the target range for the funds rate is the primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy. Last cycle, this meant that balance sheet reduction only began once normalization of the level of the funds rate was “well under way,” which in practice meant after the FOMC had hiked four times to 1-1.25%.

We make two simple observations about runoff in the last cycle. First, runoff began smoothly and—despite some confusion toward the end—successfully shrank the balance sheet to its new equilibrium size. There is no obvious problem with the prior strategy that needs to be fixed, and the Fed therefore has less reason than other central banks to rethink its approach. Second, the Fed was quite cautious in its first attempt at runoff—in particular, it provided a lengthy advance warning that runoff was coming and started at a very slow pace—but now has more experience.

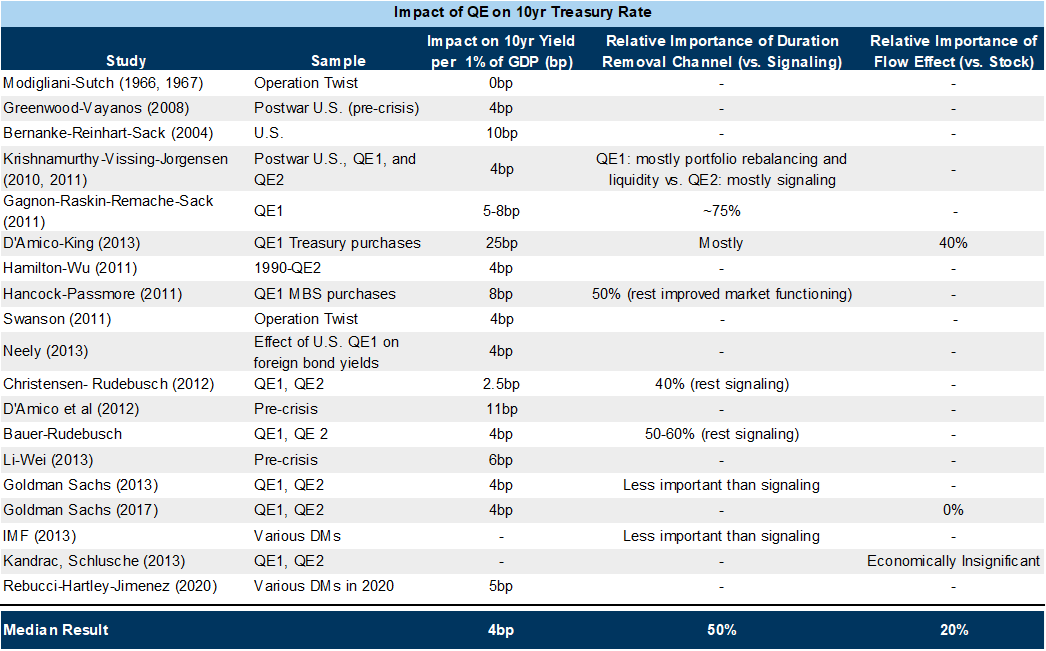

Fed officials have said that they will revisit the balance sheet normalization process. We assume that they will follow a somewhat less conservative version of the template used for runoff last cycle. We forecast that the fourth rate hike will come in 2023H1, and our best guess for now is therefore that runoff will begin around that time. Research on balance sheet policy implies that the impact of runoff on interest rates, broader financial conditions, growth, and inflation should be modest, much less than that of the rate hikes we expect. However, markets have sometimes reacted strongly to reductions in balance sheet accommodation in the past.

Early Thoughts on Fed Balance Sheet Runoff (Mericle)

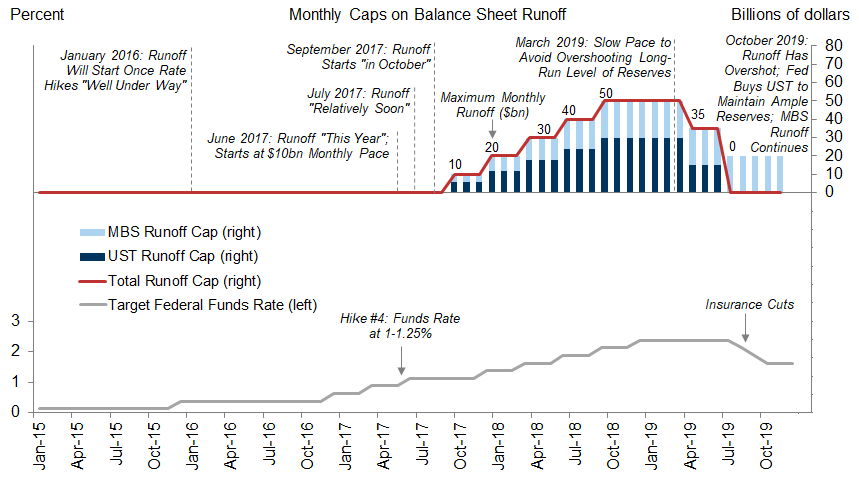

In January 2016, shortly after the first rate hike, the FOMC said that it anticipated continuing to reinvest maturing securities until normalization of the level of the fund rate was “well under way.”

In June 2017, after raising the funds rate for the fourth time to 1-1.25%, the FOMC announced that runoff would start “this year.” It also updated its normalization principles to note that runoff would begin at $10bn per month ($6bn UST, $4bn MBS) and gradually ramp up by $10bn per month every three months to a peak pace of $50bn per month.

In July 2017, the FOMC provided a second warning that runoff would start “relatively soon.”

In September 2017, the FOMC announced the start of runoff, effective the next month.

In December 2017, the FOMC resumed rate hikes after having paused them in the lead-up to runoff.

In 2018, the pace of runoff rose gradually from $10bn per month to a peak of $50bn per month.

In September 2018, the Fed began a periodic Senior Financial Officer Survey that asked banks about their “lowest comfortable level of reserve balances” in order to estimate how much it could shrink aggregate reserve balances, the liability that declines as UST and MBS run off on the asset side.

In March 2019, the FOMC slowed the pace of runoff to reduce the risk of overshooting the long-run level of reserves required by the new ample-reserves monetary policy implementation regime.

In July 2019, the Fed announced that it would stop reducing the total size of its System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio and begin to reinvest up to $20bn per month of maturing MBS in Treasury securities in order to shift the composition of the portfolio toward Treasuries over time.

In October 2019, as it became clear that runoff had overshot, the Fed resumed Treasury purchases to grow the balance sheet again in order to ensure that the supply of reserves remained ample.

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.