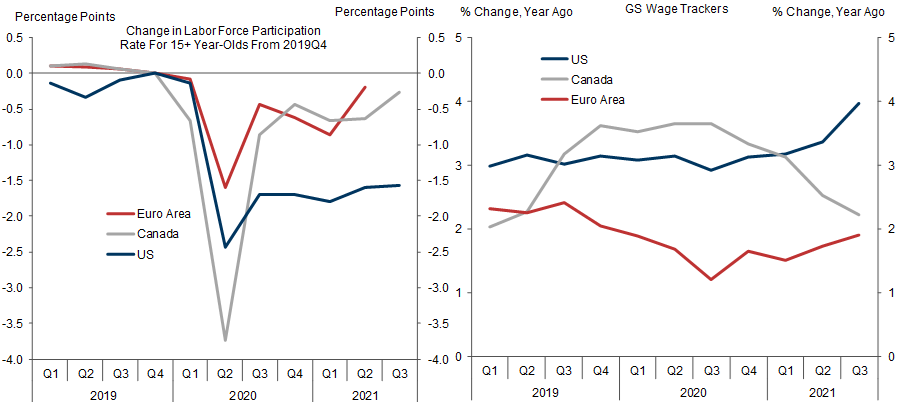

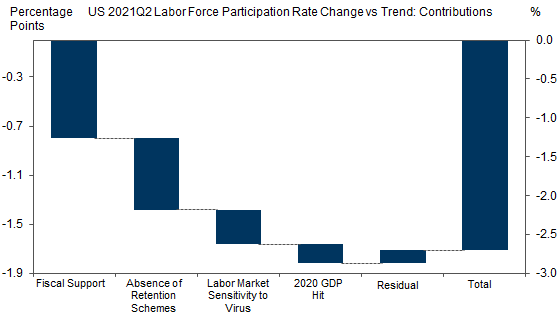

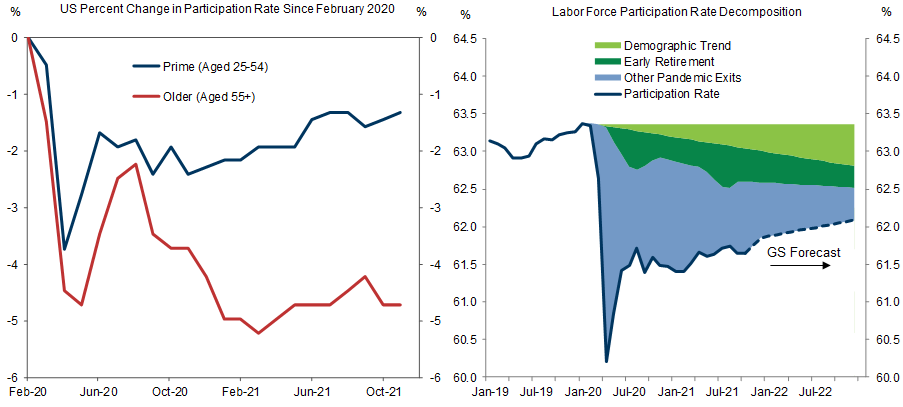

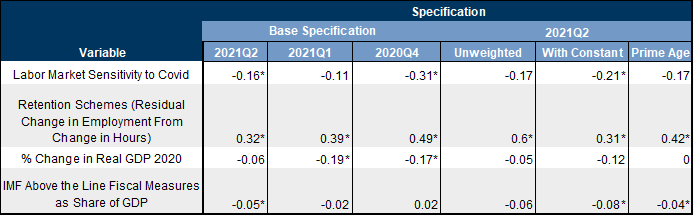

After making no progress for more than a year, the US participation rate finally edged up in November. Using a cross-country sample, we estimate the relative contributions of fiscal support, labor market policies, and virus fears to the 1½pp US participation rate decline from its 2019Q4 level.

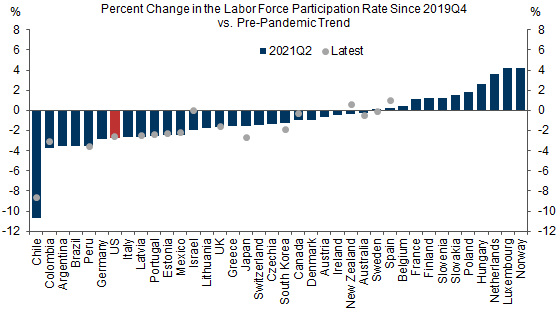

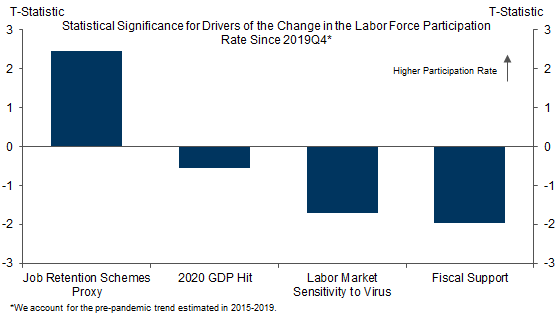

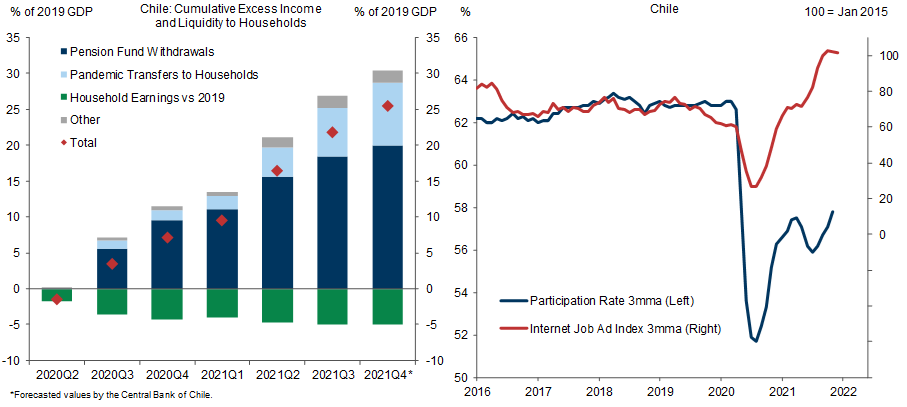

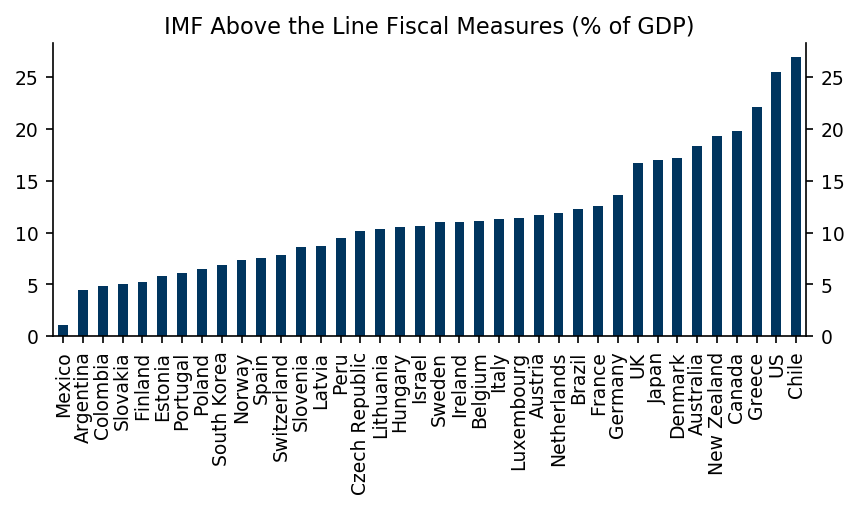

First, we attribute about one-half of the US labor force participation rate shortfall to generous fiscal support, which likely discouraged labor supply. More broadly, the participation rate has generally underperformed in economies with large increases in household liquidity. The most notable case in point is Chile, where the participation rate declined by 5pp as fiscal support and pension withdrawals flooded households with liquidity.

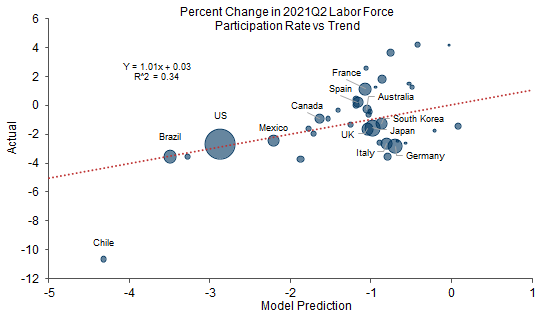

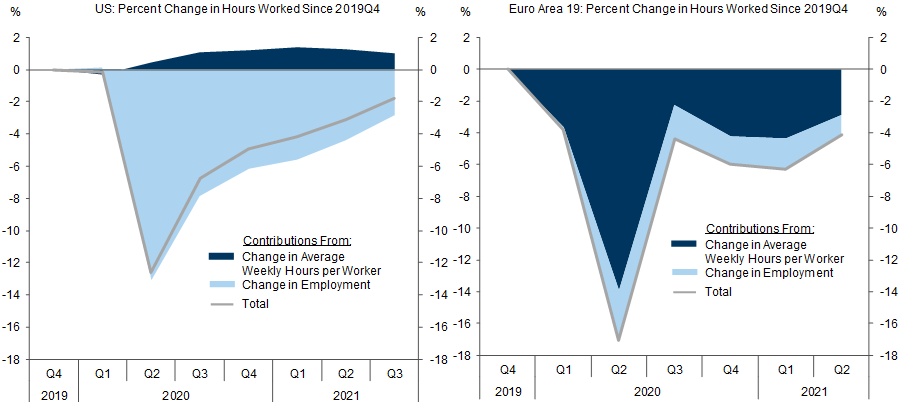

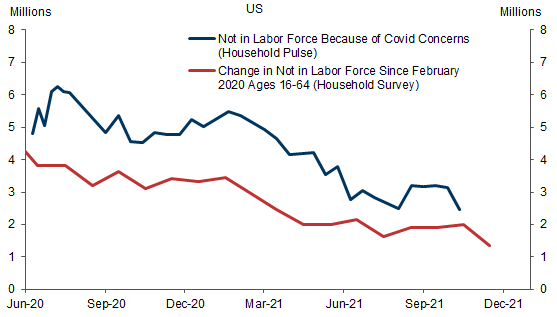

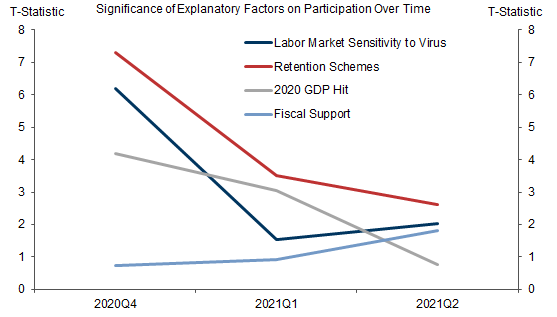

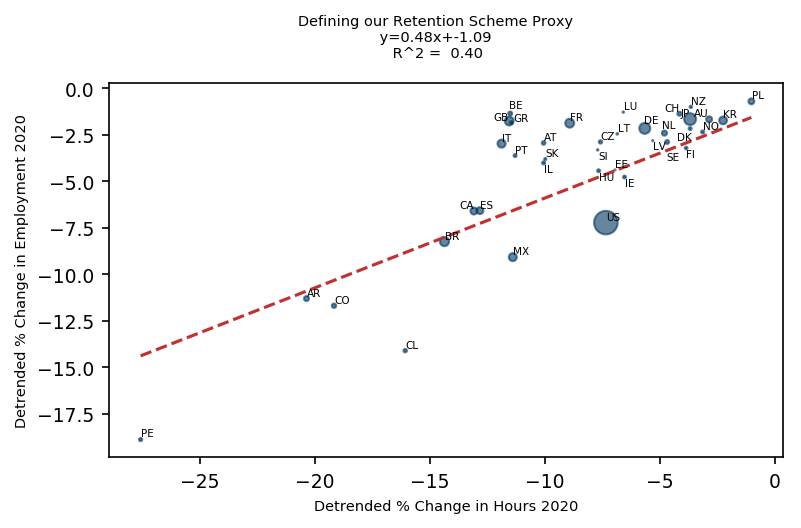

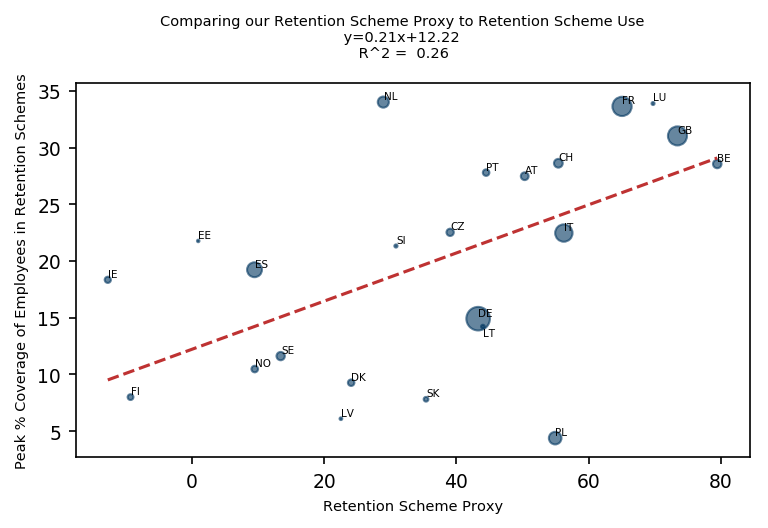

Second, we attribute about a third of the US participation shortfall to the form in which fiscal support was delivered, through generous unemployment benefits instead of job retention schemes. Such schemes kept workers attached to their employers in most of the OECD despite similarly large declines in hours worked. Finally, we estimate that the remaining one-sixth of the US participation rate shortfall reflects the labor market response to virus fears, which have likely discouraged people from returning to work. This is a smaller share than suggested by simple survey measures. The reason for the difference is that our cross-country model finds that fiscal policy factors are an even better explanation of the pattern of participation underperformance than virus fears.

A few major caveats are worth noting. First, our results are based on a relatively small sample of 38 countries. Second, data availability constrains how precisely we can measure the drivers of participation. Third, our simple model does not capture variables that we cannot measure consistently and have likely also weighed on US participation, such as large wealth increases.

With these caveats in mind, we expect the US participation rate to rise by ½ pp to 62.2% by end-2022. We expect a diminishing fiscal drag on participation as savings are run down, and find that the statistical importance of job retention schemes and virus fears for participation is declining. However, we expect the participation rate to remain structurally below its pre-pandemic trend, as job losses have triggered permanent labor force exits, especially for older workers.

Why Is US Labor Supply So Low? (Milo/Struyven)[1]

Measuring and Modeling Drivers

Explaining US Underperformance

A Partial Participation Rebound Ahead

Appendix

- 1 ^ We thank the US, Europe, Latin America, Asia-Pacific, and CEEMEA economics teams for their contributions to this piece.

- 2 ^ We exclude spending/foregone revenue in the health sector.

- 3 ^ We also detrend hours worked and employment using the 2015-2019 average.

- 4 ^ The proxy does not capture workers who stayed out of the labor force the entire pandemic due to virus fears, and does not distinguish between labor force exit and work from home.

- 5 ^ Golosov, Mikhail, et al. “How Americans Respond to Idiosyncratic and Exogenous Changes in Household Wealth and Unearned Income,” No. w29000. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021.

- 6 ^ See Table 2 of Athreya, Kartik, Andrew Owens, and Felipe Schwartzman. "Does redistribution increase output? The centrality of labor supply." Quantitative Economics 8.3 (2017): 761-808.

- 7 ^ See Jan Hatzius and Daan Struyven, “A Global Perspective on the US Unemployment Crisis”, Global Economics Analyst, 26 May 2020,

- 8 ^ Home price growth was not a statistically significant driver of cross-country changes in the participation rate in our model.

- 9 ^ Retention schemes have ended in some economies but not others. The positive effect of retention schemes on participation could diminish further over time if previously furloughed workers exit the labor force. In practice, the share of workers on furlough schemes is now relatively small (e.g. 2% in France), and the UK furlough scheme seems to have ended without significant disruptions.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.