We continue to expect persistent pandemic-driven efficiency gains, for three reasons: 1) Strong cumulative productivity gains in 2020-21 in both official and alternative metrics, 2) The incidence of these gains within digitizing industries, particularly those where Work-from-Home is effective, and 3) The sheer scale of the changes to the workforce and to company business models since 2019.

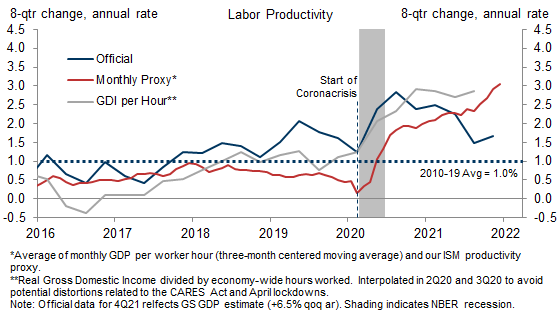

Productivity in the nonfarm business sector has increased at a 1.7% annualized pace over the last two years—compared to the +1.0% trend pre-pandemic. GDP data are often revised around recessions, and both our ISM productivity proxy and Gross Domestic Income per hour suggest an annualized pace closer to +3% over this period.

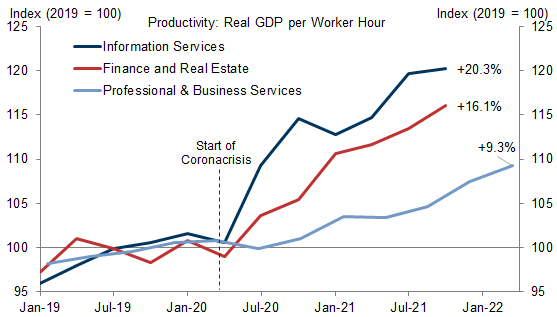

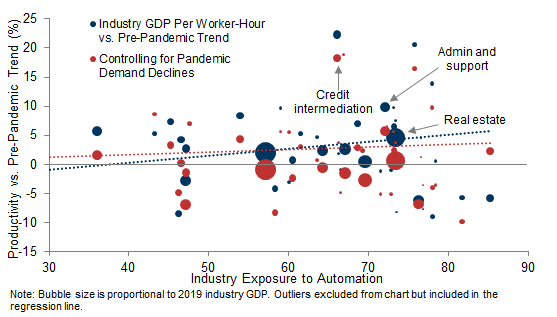

We also find that the incidence of productivity gains is skewed towards industries ripe for digitization, such as IT services (+11.9% annualized productivity growth since 4Q19) and professional services (+5.5%). Additionally, we find that Work-from-Home adoption and the scope for labor automation correlate positively with productivity acceleration across 54 subindustries—even after controlling for negative pandemic demand shocks.

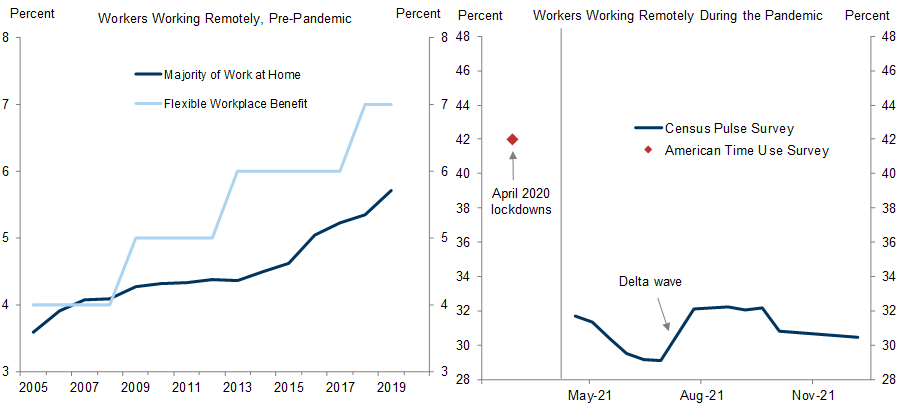

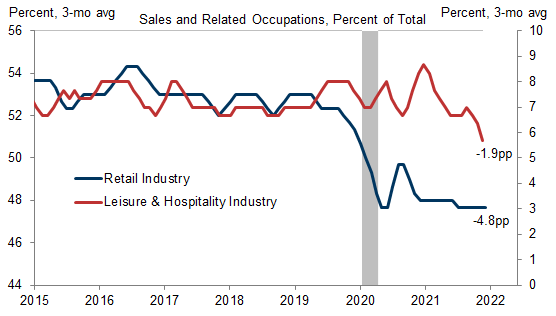

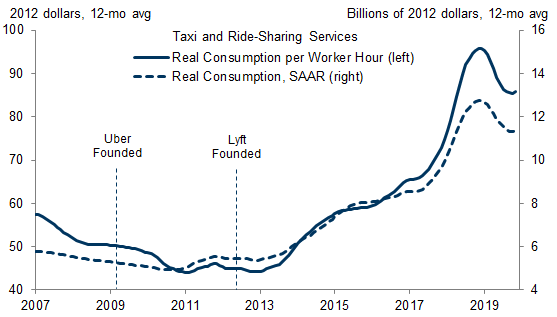

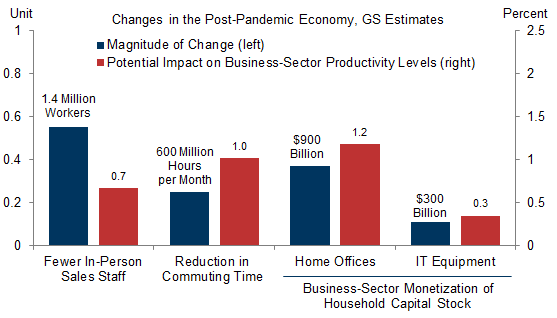

The sheer scale of pandemic-driven changes to the workforce and to company business models also argues for a large and long-lasting productivity inflection. These changes include 600 million fewer hours spent commuting every month, as well as possibly 1.4 million fewer cashiers, in-person salespeople, and office maintenance staff. Many of these workers and hours will be reallocated to more productive uses—especially at a time of labor shortages and near-record job vacancies. We also estimate around $900bn worth of home offices and $300bn of consumer IT equipment is now available for business-sector use. This echoes the output and productivity boom in the ride-sharing industry during the 2010s, when Uber and Lyft successfully monetized the household capital stock of cars.

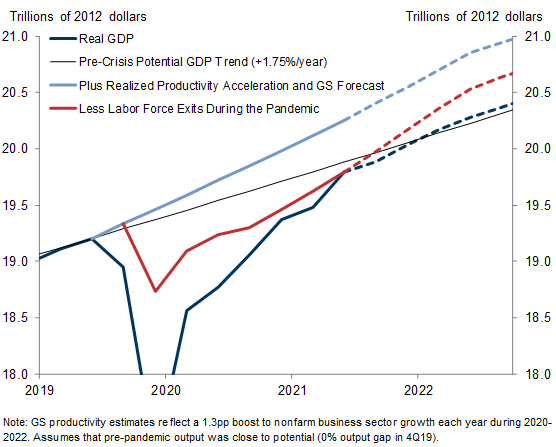

Incorporating these four baseline estimates into a top-down production function of the economy, we estimate a persistent boost to the level of private-sector productivity of 3-4% (or 1.0-1.3pp per year during 2020-22). We expect these efficiency gains to offset the decline in labor supply caused by the pandemic, in turn implying a longer runway for expansion. They also support our forecast of a more normal inflation environment in the medium-term once pandemic dislocations begin to recede.

Productivity Gains Will Outlast the Pandemic

Crisis-to-Date Productivity Trends

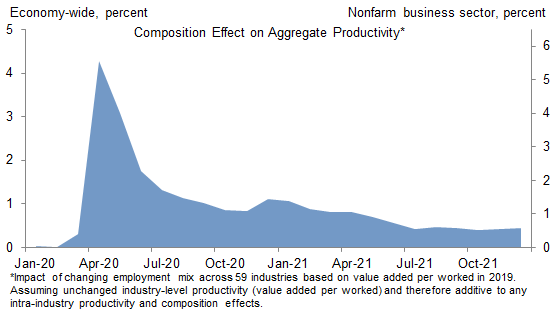

Industry Composition of the Productivity Pickup

The Post-Pandemic Workforce

Room to Run

Exhibit 11: Scale of Pandemic-Driven Workforce Changes Argues for One-Time Productivity Gains of at Least 3%

Spencer Hill

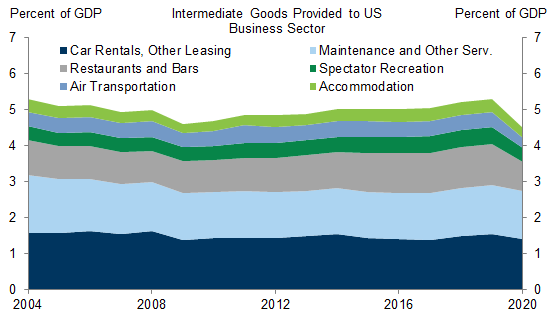

- 1 ^ Commercial real estate is one key exception whose use as an intermediate input has not yet declined (as a share of GDP). To the extent that offices downsize or adopt shared workspaces after the pandemic, this offers a significant opportunity for additional productivity gains—specifically as the floor space is sold to other businesses or reallocated to residential or retail uses.

- 2 ^ Some of the transportation weakness may also be virus-related—reflecting weaker consumer demand or supply inefficiencies caused by the pandemic.

- 3 ^ Many of these workers and hours will be reallocated to more productive uses—especially at a time of labor shortages and near-record job vacancies.

- 4 ^ The net exit of unprofitable or inefficient businesses that occurs during and in the wake of recession.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.