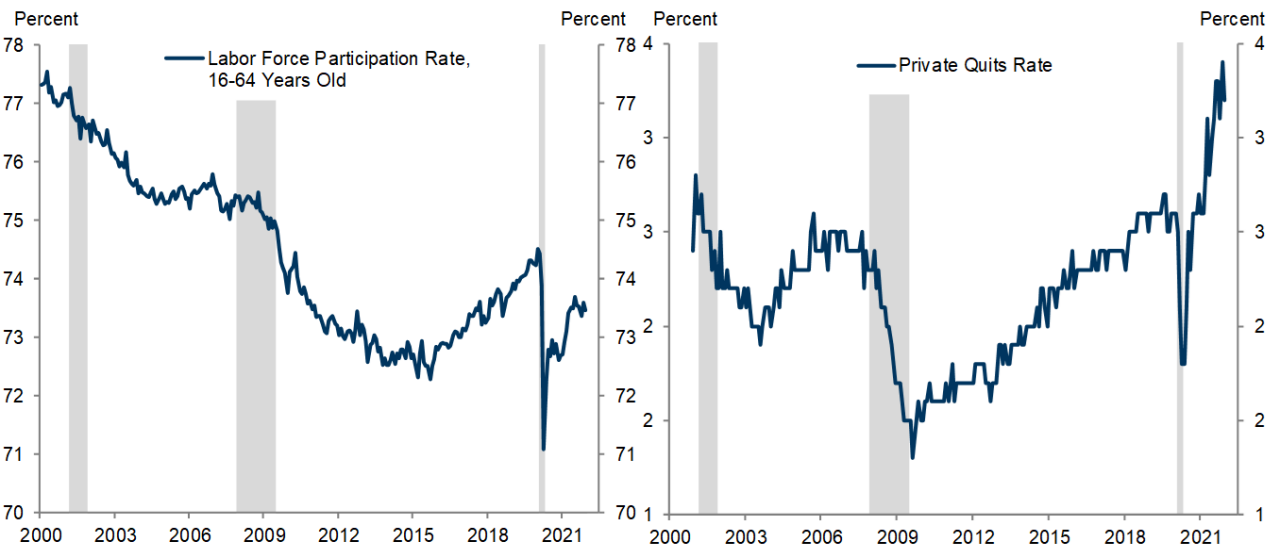

The Great Resignation consists of two quite different but connected trends: millions of workers have left the labor force, and millions more have quit their jobs for better, higher-paying opportunities. These trends have pushed wage growth to a rate that increasingly raises concern about the inflation outlook.

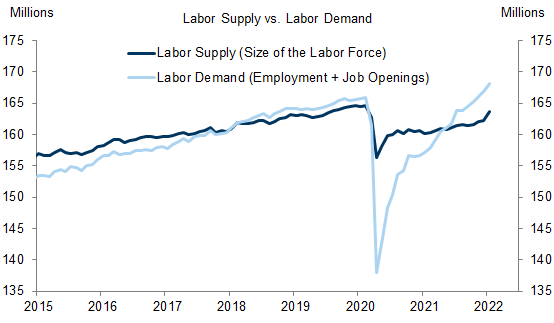

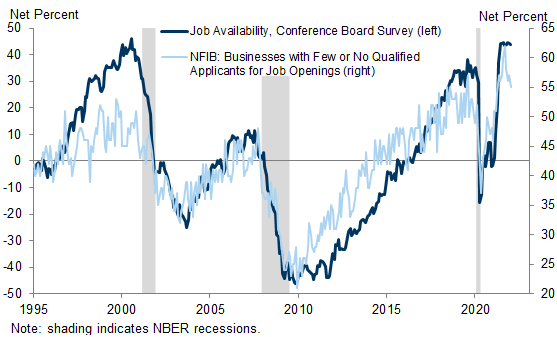

How did the US wind up with a historically tight labor market so soon after a recession? While total labor demand—employment plus vacancies—is roughly in line with its pre-pandemic trend, labor supply remains substantially depressed.

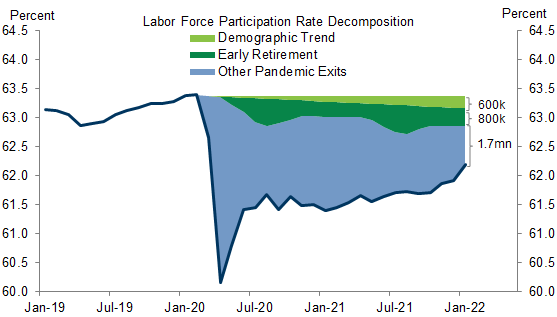

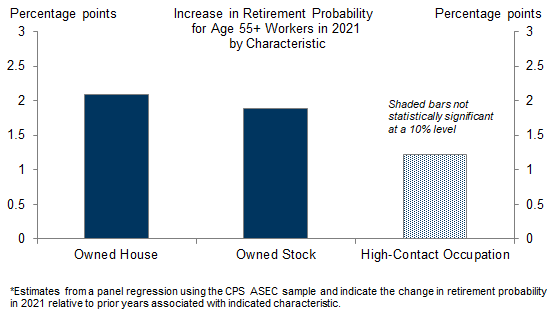

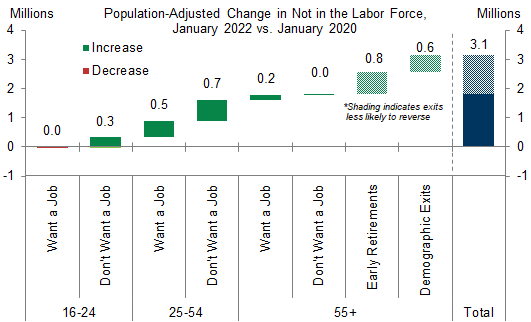

The most visible sign of depressed labor supply is that the participation rate remains 1.2pp below its pre-pandemic rate. This gap consists of a 0.2pp drag from population aging and an unexpected 1pp drag—equivalent to 2½ million missing workers—from other factors. Roughly 0.8 million of these have retired early, many having benefited from rising home and equity prices. This leaves 1.7 million people who are more likely candidates to return to the labor force.

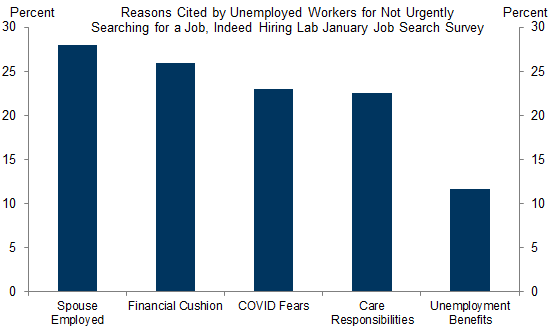

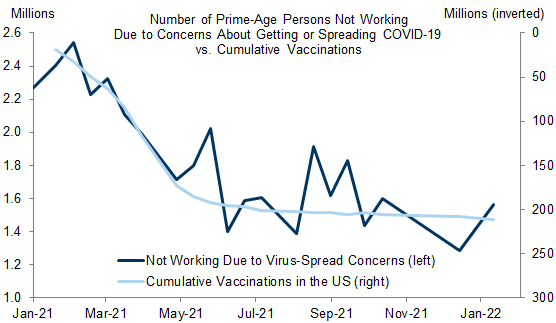

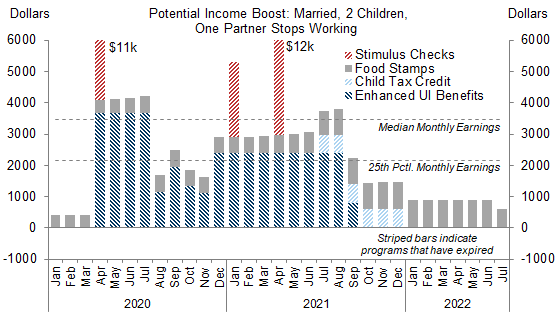

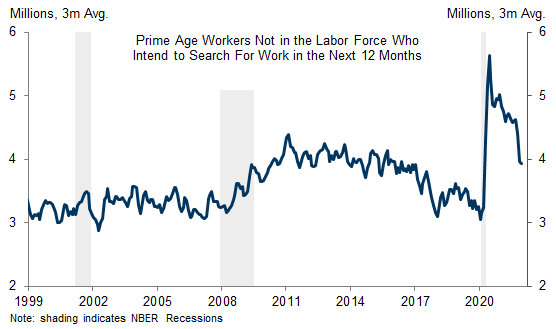

Why haven’t those 1.7 million come back yet? Workers give three main reasons: they have Covid-related concerns, they have a financial cushion, or their lifestyle has changed. These explanations suggest that some people are likely to come back if virus spread falls or antiviral pills reduce health risks, and others are likely to come back once they exhaust their savings, especially now that most special pandemic fiscal transfer payments have expired. In support of this expectation, most prime-age workers who left the labor force say they intend to re-enter.

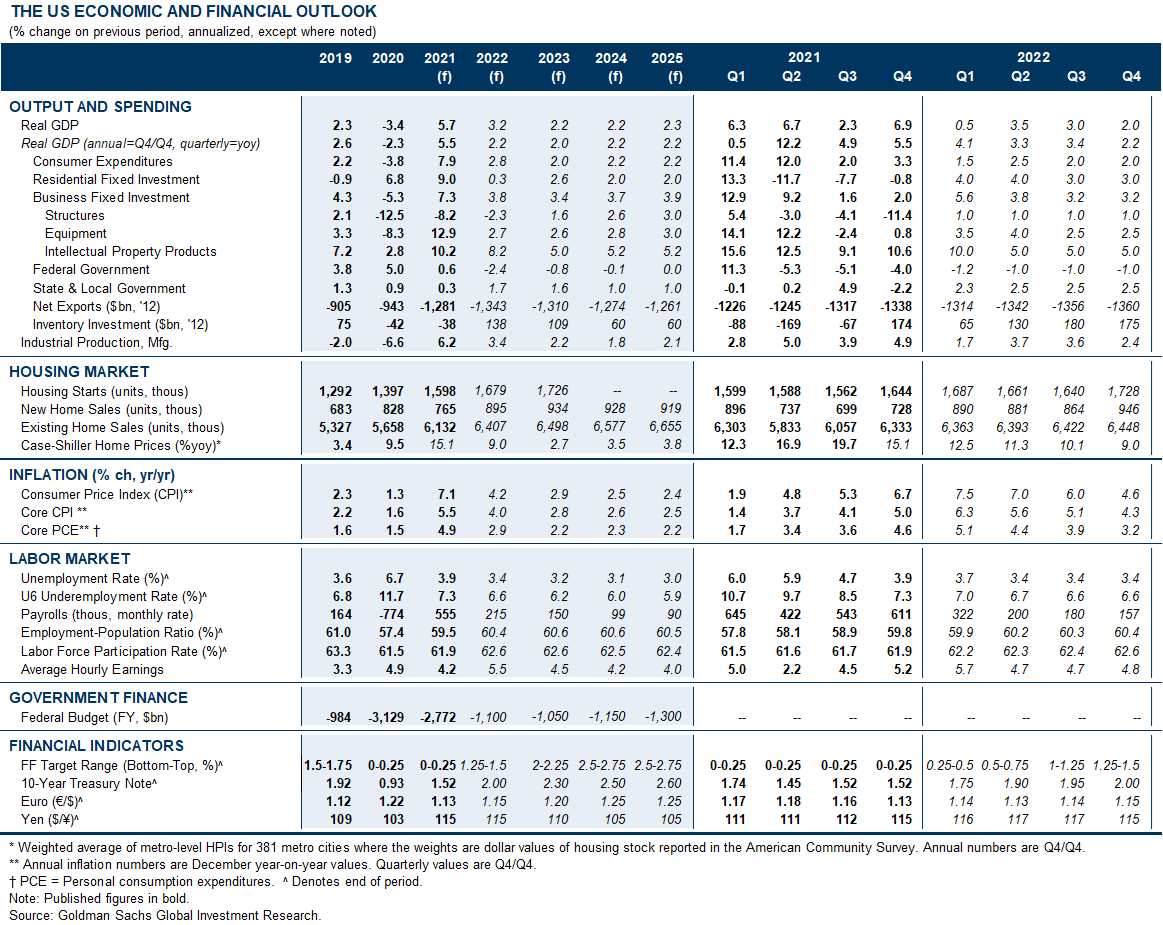

We forecast that about 1 million people will return to the labor force this year, raising the participation rate to 62.6% by year-end, and that more will come back in later years. Even so, the depressed participation rate implies that workers will be even harder to find than the unemployment rate suggests.

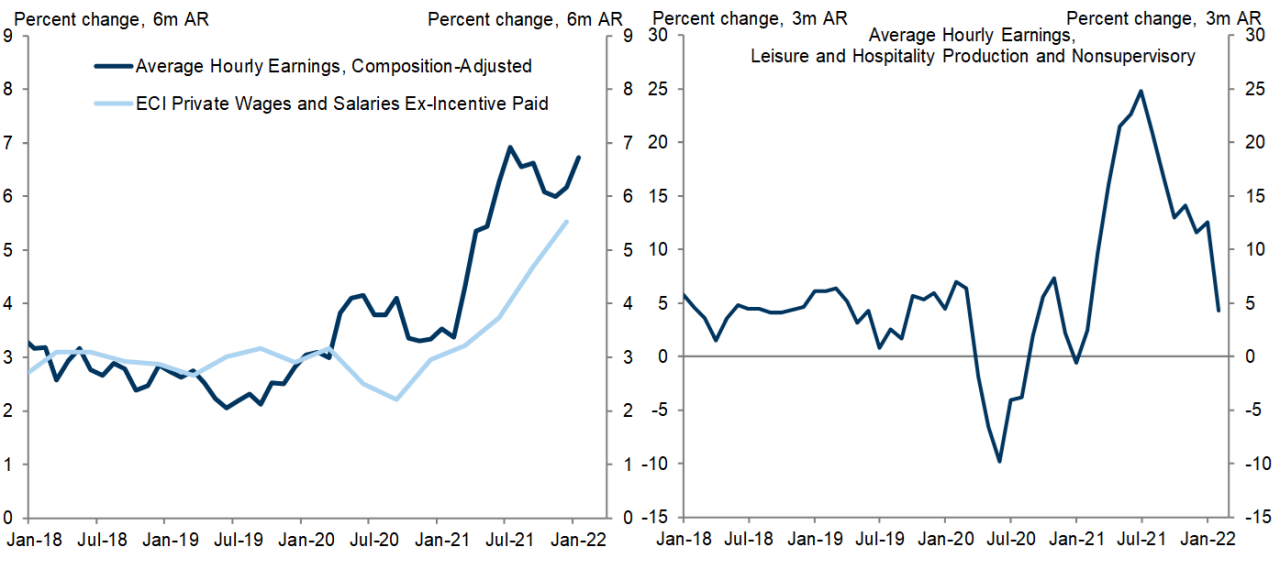

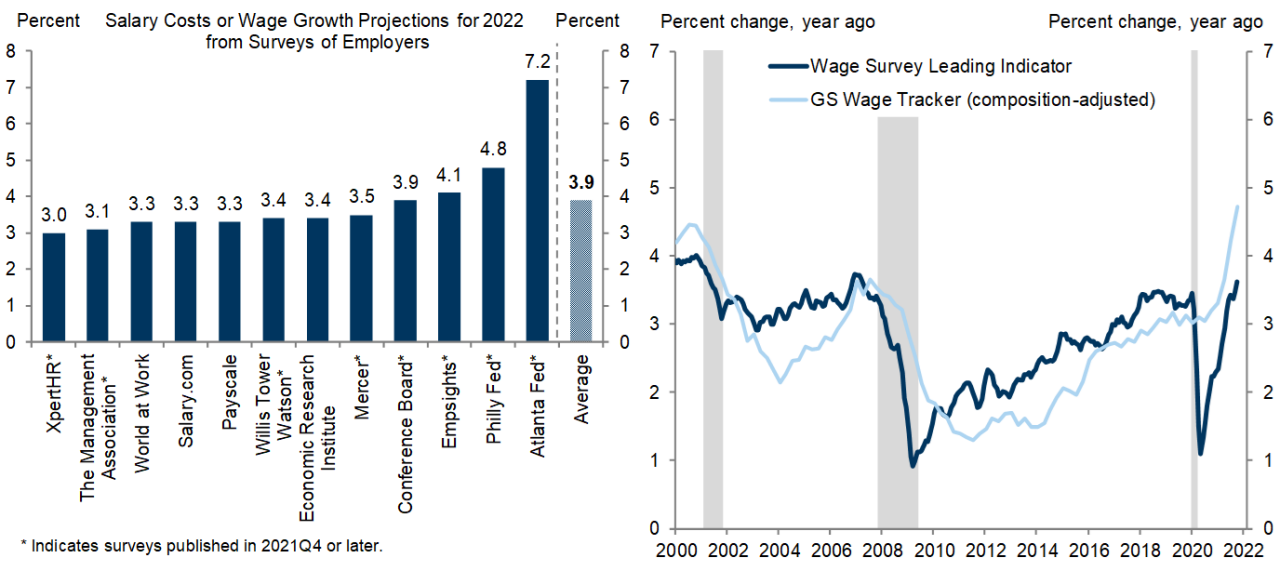

The tight labor market has boosted wage growth to a 6% pace, perhaps with an assist from high inflation expectations. But surveys show that employers expect wages to rise at a more sustainable 4% pace this year. We put weight on both signals and therefore forecast 5% wage growth this year, implying 3% unit labor cost growth after netting out 2% productivity growth. Faster growth of labor costs than is compatible with the 2% inflation goal is likely to keep the FOMC on a consecutive hiking path and raise the risk of a more aggressive response.

Missing Workers and Rising Wages

Why Is the Labor Market So Tight?

Who Left the Labor Force?

Will the Workers Come Back?

The Risks for Wage Growth, Inflation, and the Fed

Joseph Briggs

David Mericle

- 1 ^ We are not considering the decline in immigration in 2020 here because it affects both labor supply and labor demand, since immigrants who did not come to the US do not consume in the US either. We discussed this at length in an earlier piece.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.