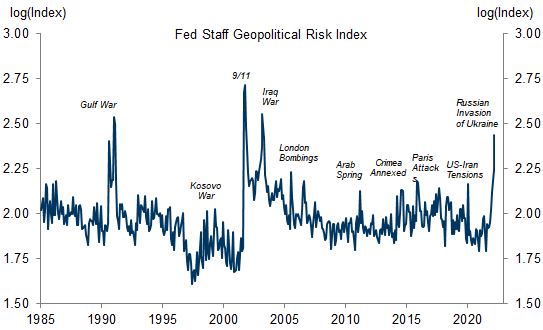

Two recent shocks have opened the eyes of US companies to the importance of supply chain resilience. The pandemic brought lockdowns, shipping gridlock, and shortages that resulted in the worst supply chain disruptions in decades and lost revenues for many affected companies. More recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused a sudden loss of foreign assets and trade relationships that has reminded companies of their exposure to geopolitical risk as well.

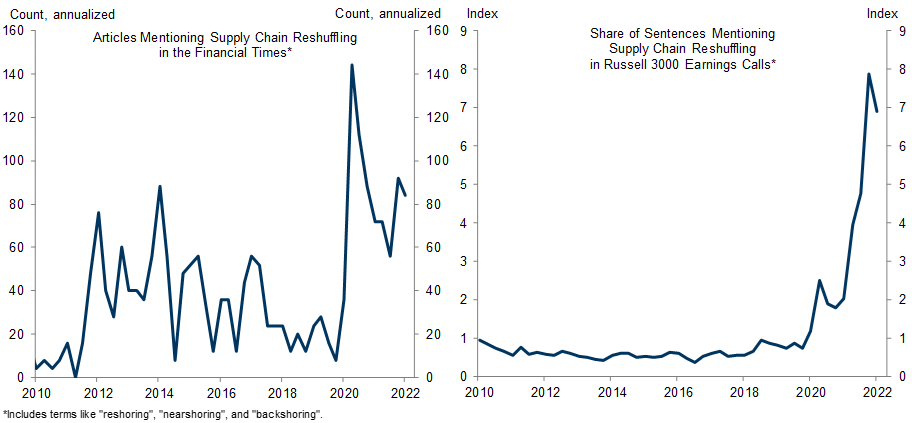

Last cycle, the media hyped a “manufacturing renaissance” in the US that never amounted to much. But this time companies really are focused on strengthening supply chain resilience. We explore three forms that this could take: reshoring foreign production to the US, diversifying supply chains, and overstocking inventories.

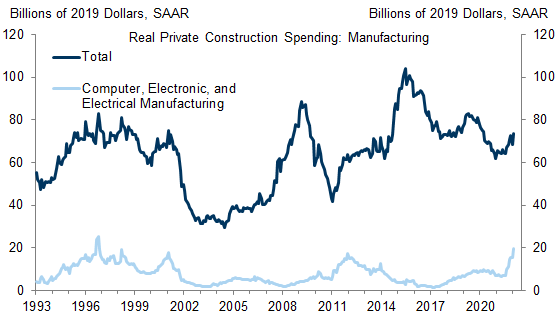

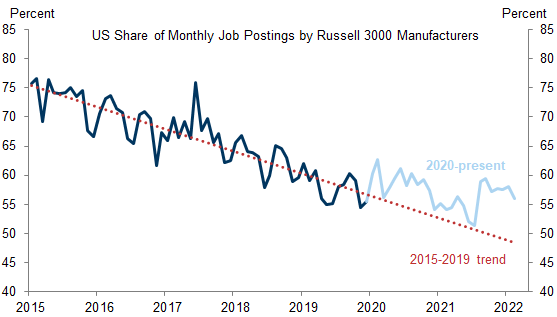

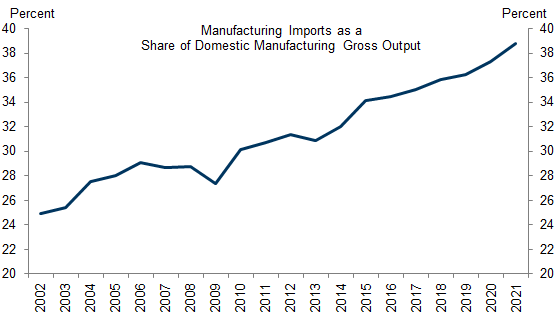

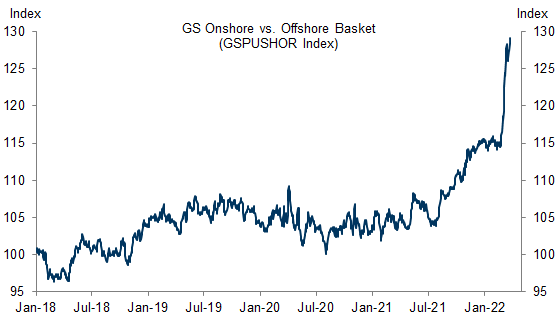

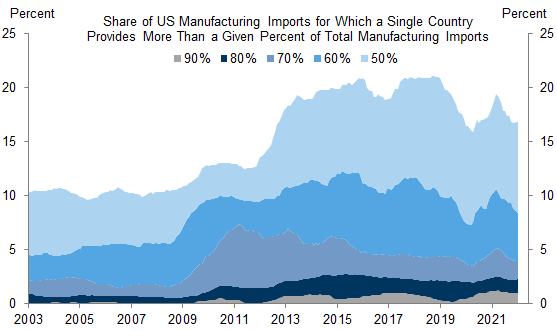

Reshoring appears limited so far. Construction of new domestic manufacturing facilities has mostly gone sideways, and imports of foreign parts and final goods have continued to grow faster than domestic manufacturing output. It might, however, simply be too soon to see the shift: the outperformance of US companies exposed to reshoring relative to US companies exposed to offshoring suggests that the market expects some eventual move in this direction.

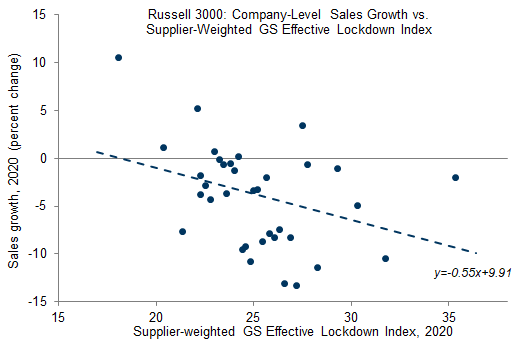

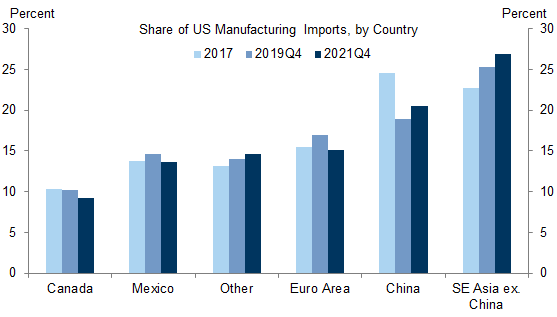

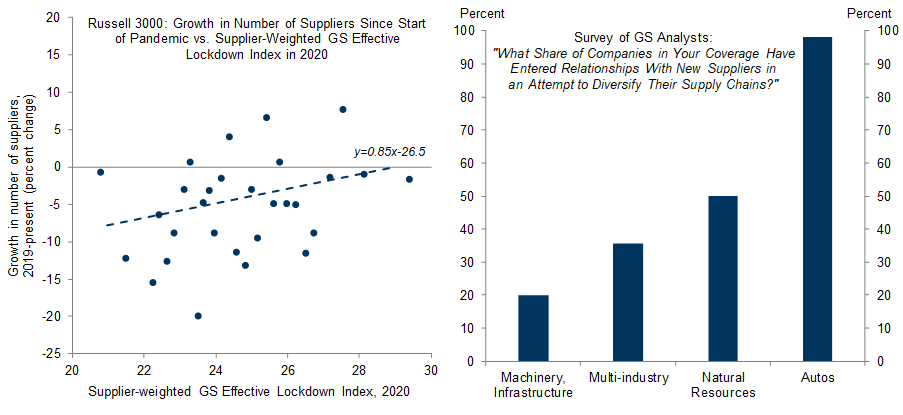

Supply chain diversification appears to be further along. We find that companies that relied more on suppliers in countries that imposed stricter virus restrictions had weaker revenue growth in 2020 and then became more likely to broaden their supplier base in 2021.

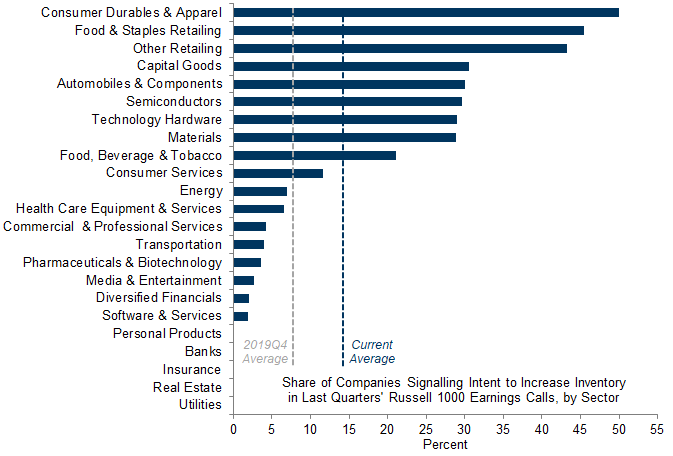

Inventory overstocking is the strategy for improving supply chain resilience that is most clearly underway. Earnings call transcripts show that the share of companies that report plans to target a permanently high level of inventory has increased sharply, especially in durable goods sectors. Our manufacturing sector analysts corroborate this and report that companies in their coverage are targeting inventory-to-sales ratios roughly 5% higher than before the pandemic on average.

Greater supply chain resilience comes at a price, and some investors worry that these trends will add to inflationary pressures. But the costliest of the three responses—reshoring production to the US—is also the least underway, suggesting that the shifts to date are a second-tier influence on the inflation outlook relative to key macroeconomic forces like labor market overheating.

Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience: Reshoring, Diversification, and Inventory Overstocking

Exhibit 1: US Companies with Greater Exposure to Suppliers in Countries That Locked Down Heavily Experienced Larger Revenue Declines in 2020

Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience

Response #1: Reshoring

Response #2: Supplier Diversification

Exhibit 10: Firms with Greater Exposure to Suppliers That Were Hit by Lockdowns Were More Likely to Expand The Number of Suppliers They Depend On

Response #3: Inventory Overstocking

The Cost of Resiliency

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ For example, see Lindsay Oldenski, “Reshoring by US Firms: What Do the Data Say,” 2015 or “Kearney Reshoring Index,” 2021.

- 2 ^ Some definitions limit “reshoring” to the transfer of intracompany activities back to the US from abroad (see Koen De Backer et al., “Reshoring: Myth or Reality?” 2016), but we use a wider definition that allows for intercompany sourcing (which is sometimes also referred to as “backshoring”).

- 3 ^ For examples, see Robert Lighthizer, “The Era of Offshoring U.S. Jobs Is Over,” 2020.

- 4 ^ Trang Hoang, “The Dynamics of Global Shipping,” 2022.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.