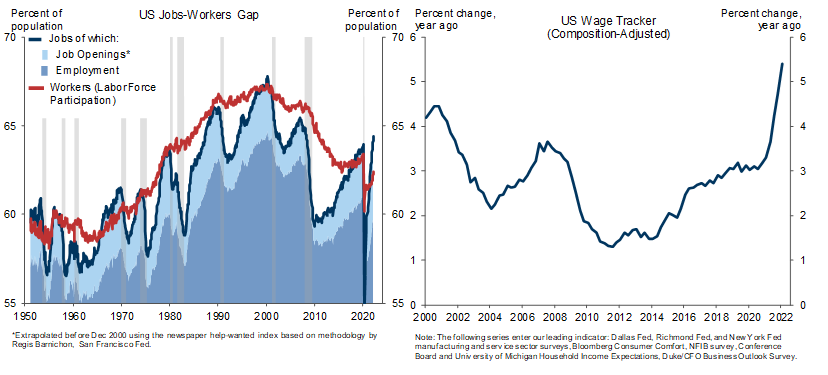

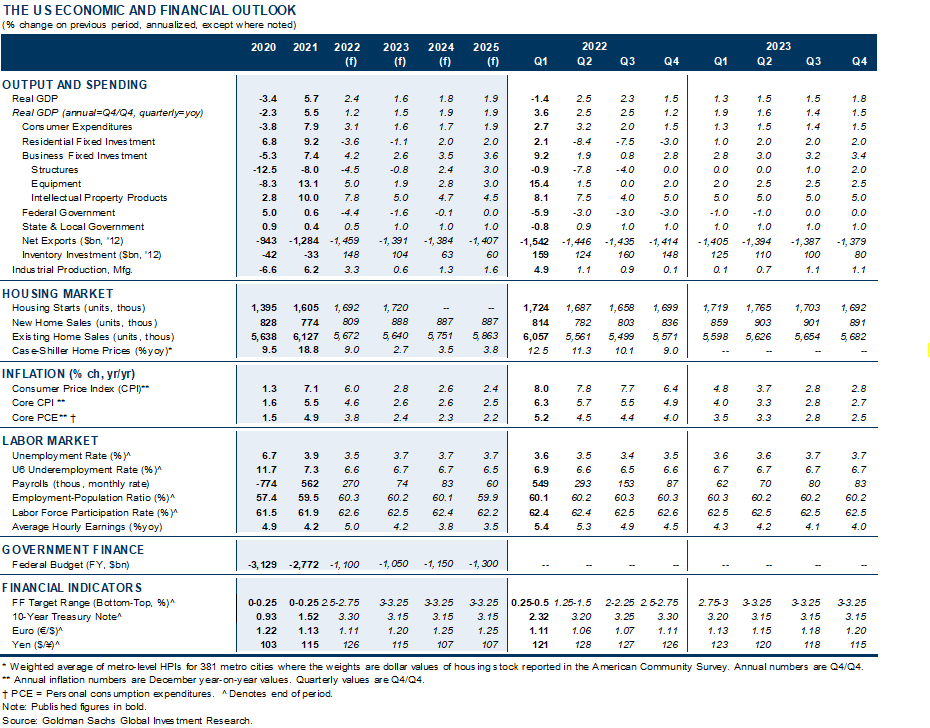

The gap between the number of available jobs and the number of available workers has allowed wages to rise at a rate well above the pace of wage growth compatible with the Fed’s inflation goal. While reduced labor force participation is primarily behind the lower number of available workers, reduced immigration has also played a role.

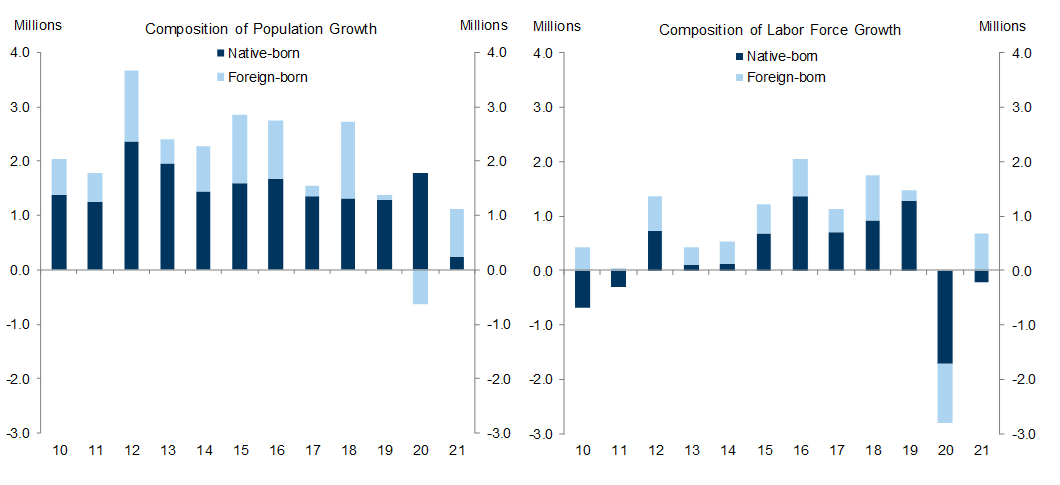

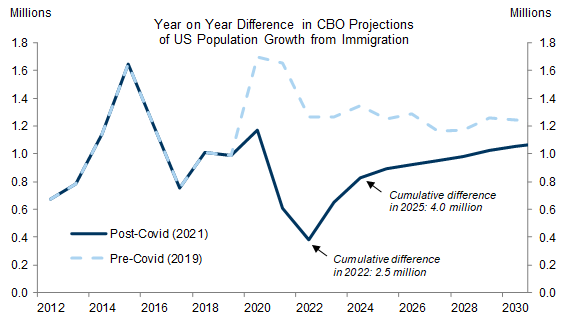

From 2010 to 2018, foreign-born workers accounted for nearly 60% of the growth in the US labor force, but growth in the foreign-born population slowed to around 100k/yr between 2019 and 2021, leaving the US population around 2 million smaller than it would otherwise have been, and the labor force around 1.6 million smaller.

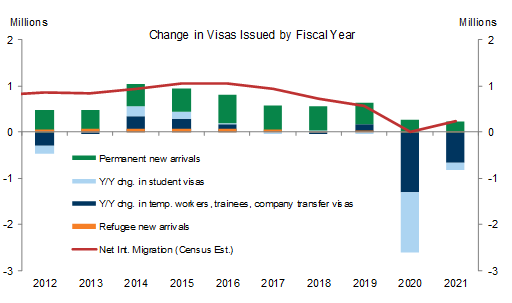

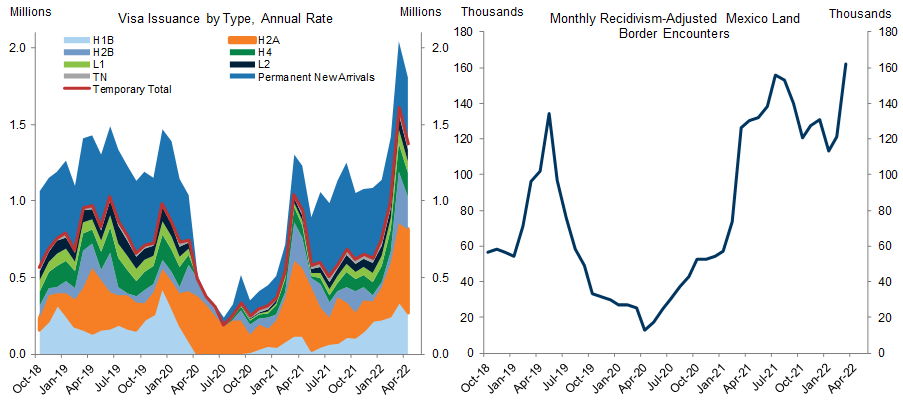

More recently, immigration has rebounded. Green card issuance to new arrivals has roughly returned to its pre-pandemic level, and temporary work visas have gotten close to normal levels in just the last few months.

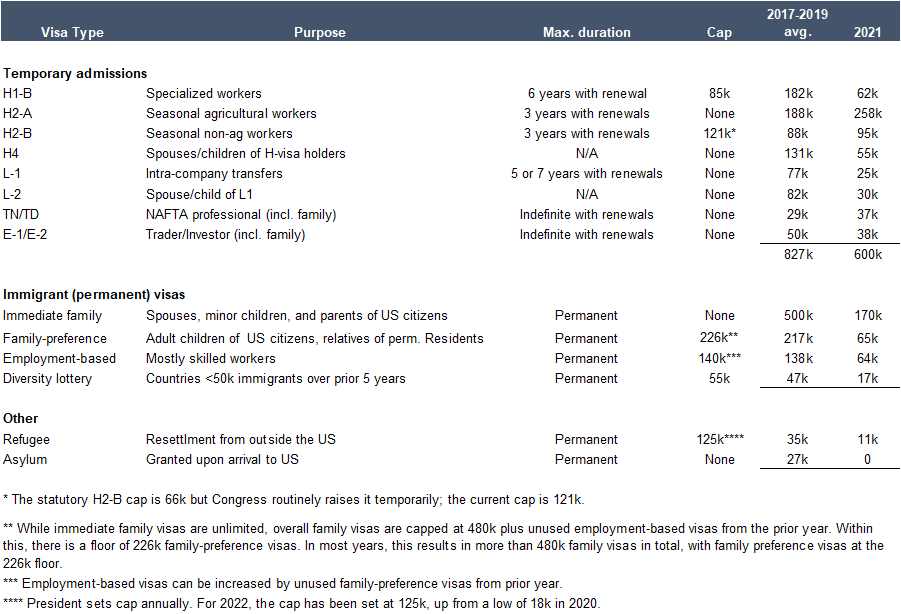

However, immigration rates would need to increase further to make up the shortfall in foreign born workers. Immigration policies could make that difficult, as many immigration categories, including skilled and unskilled temporary workers, are limited by numerical caps that only Congress can change. While we would not rule out near-term congressional changes to the caps on lower-skilled workers in particular, broader legislative changes look unlikely.

There are some administrative steps the administration could take. Waiving interviews and expediting other aspects of the green card process could clear backlogs; reinterpreting the application of numerical limits, allowing spouses of all temporary workers to work, and recapturing unused visa allocations from prior years could each boost net migration by around 200k.

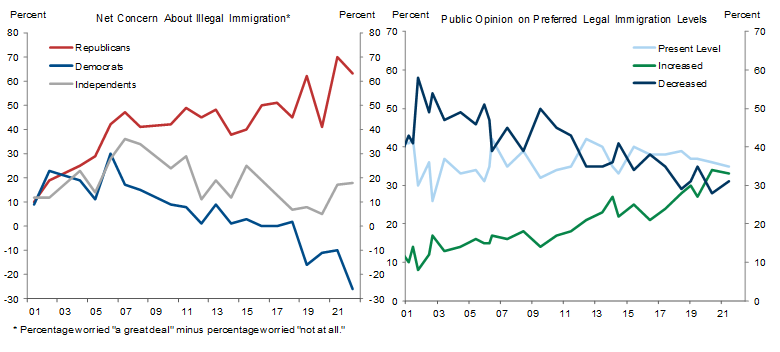

That said, major immigration changes might not be politically realistic even if there is procedural flexibility to make them. While easing inflation would have clear political benefits and there appears to be some public support for increased legal immigration, substantial changes seem unlikely before the midterm election in November.

It seems more likely that the Biden Administration will make modest changes where there is clearer authority to do so, perhaps increasing net migration by a few hundred thousand above the normal pace. This would make a modest dent in the jobs-workers gap, but would still leave most of the work for the Fed.

Could More Immigration Make a Dent in the Jobs-Workers Gap?

Immigrant and nonimmigrant visa ban: In April 2020, President Trump issued a proclamation temporarily suspending issuance of most categories of employment-based and family-based green cards. This expanded in June to also cover several non-immigrant categories, including H1-B and H2-B skilled and unskilled worker visas. President Biden rescinded these in February 2021.

Public charge: US law prohibits visa issuance to anyone who is likely to become a “public charge” but this had not generally been an obstacle for green card applicants as they were not eligible for most public benefits in any case. The Trump Administration tightened the restrictions under this policy which led to the denial of some green card applications. The Biden Administration stopped applying the rule in March 2021.

Lower refugee caps: The president sets a cap each year on the number of refugees, which has averaged around 75k per year over the last few decades. This was cut roughly in half during the Trump Administration and reached a low of 18k in 2020. For 2022, the Biden Administration has set a cap of 125k.

“Remain in Mexico”: In 2019, the Trump Administration implemented the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which requires asylum seekers to await their court dates outside the US, rather than detaining them or releasing them into the US while awaiting a ruling. The Biden Administration attempted to reverse the policy, but was blocked by a federal court, so the policy remains in place pending a Supreme Court decision expected by June.

Title 42: In response to the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued an order that prohibited many migrants from entering the US and led to the immediate expulsion of most individuals who crossed the border without authorization. This prevented migrants from seeking asylum and reduced the number of unauthorized migrants who were released into the US pending adjudication. However, it also reduced the consequences for unauthorized border-crossers, who would not face criminal penalties or detention. The Biden Administration has announced that the policy will end on May 23, though pending federal litigation may extend that date.

A reduction in the administrative backlog. Immigrant visa approvals have nearly caught up with pre-pandemic levels, but there continues to be a substantial backlog—421k applicants as of April 2022—of approved petitions awaiting interview. Expediting or waiving those interviews would likely lead to a bump in approvals.

A different application of numerical limits. Even if the administrative backlog is cleared, most visa categories have statutory limits on the number issued each year, which could prevent a surge in visa issuance out of the backlog. Some immigration law experts have asserted that the State Department could, under existing law, count only the primary applicant toward the cap, excluding “derivative” visas for spouses and minor children who currently form around 40% of total immigrant visas issued under the caps. Although only some of these visas go to new arrivals, such a change might still allow for around 175k newly arriving immigrants per year.

Authorization for more non-employment visa-holders to work. Most spouses of H1-B (skilled worker) and L-1 visa holders are currently allowed to work, but family members of most other non-immigrant visa types are not, including H2-A (agricultural) and H2-B (non-agricultural) workers. Workers in those categories typically do not bring family members, likely in part because of the prohibition. As of 2019, there were nearly 200k dependents of visa holders who lacked work authorization. If H2 visa holders brought family members in the same ratio as H1-B visa holders—this seems likely if they were allowed to work—this might increase temporary migration by another 200k or so.

Unused visa recapture. Although immigration law calls for the rollover of unused visa allocations to the following year, quirks in the law often lead to some green card allocations disappearing instead. Congress has approved legislation in the past to recapture some of the unused allocation, and current sponsors of visa recapture legislation estimate that green card issuance has undershot the numerical limit by a cumulative 400k from 1992 through 2021 (another estimate puts the cumulative undershoot in green card issuance since 1922 at 4.5 million, though it is extremely unlikely Congress or the Biden Administration would reach back this far). Of the 400k in unused visa allocations, more than 200k are from FY2021 (Oct. 2020 start), but most of these will automatically roll over to employment-based visa allocations for 2022. This will roughly double the limit on employment-based green cards this year.

Broader use of extraordinary authorities. The Administration has particular discretion when it comes to refugees and asylum seekers. The president is responsible for setting the cap on refugee admissions (125k for FY2022) and there is no cap on grants of asylum (the share of asylum requests granted has risen from less than 30% in 2020 to 50% currently). David Bier of the CATO Institute proposes raising the refugee cap to clear the backlog of family-based visa applications from countries that qualify that already have a substantial number of asylum seekers. In comments to the USCIS, immigration lawyer Cyrus Mehta proposes using “parole” authority to clear the visa backlog, modeled on smaller programs for certain countries (e.g. Haiti). This could allow for the entry of anywhere from a few hundred thousand to a few million immigrants, if it were deemed legally permissible.

Alec Phillips

We thank Tim Krupa for his contributions.

- 1 ^ For a useful compendium of potential administrative actions to liberalize US immigration policies, see David Bier, et. al, Deregulating Legal Immigration: A Blueprint for Agency Action. Most of the options listed are discussed in more detail in this report.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.