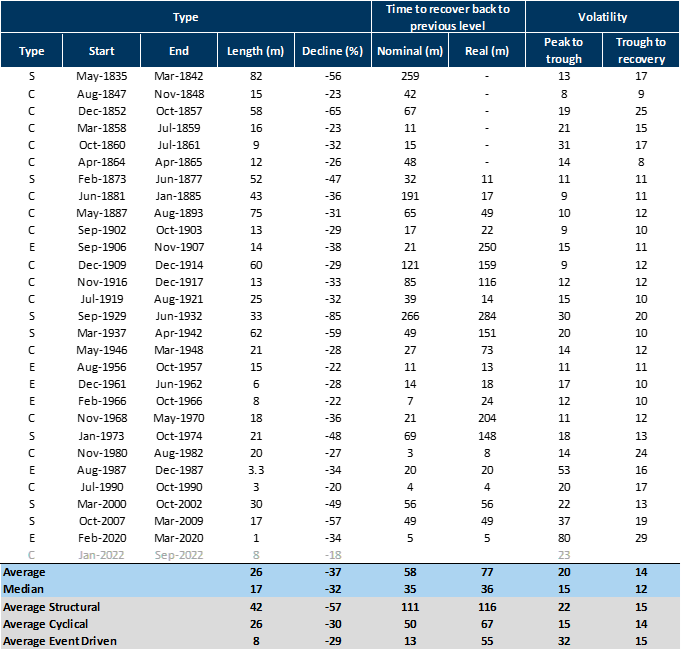

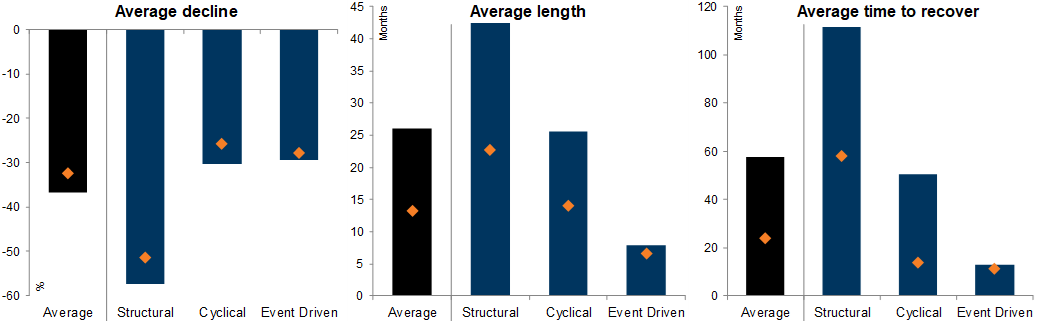

Bear markets can be split into three categories: Structural, Cyclical and Event-driven.

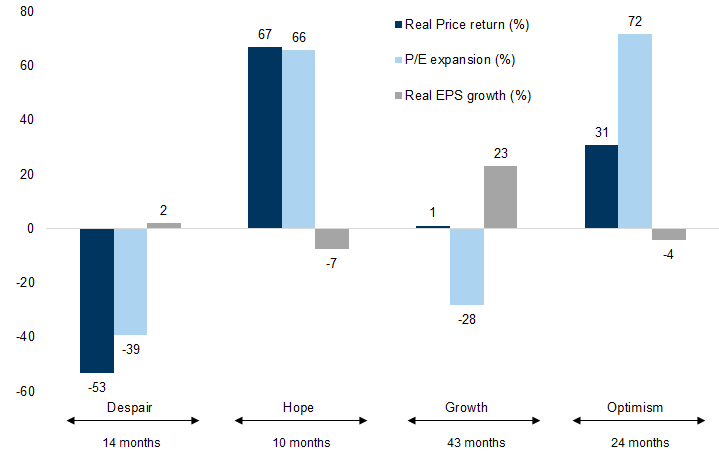

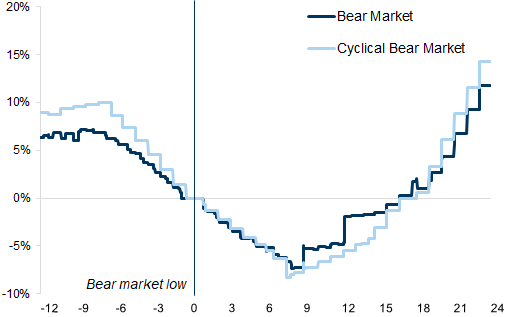

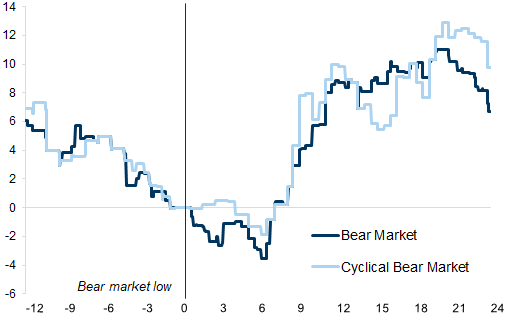

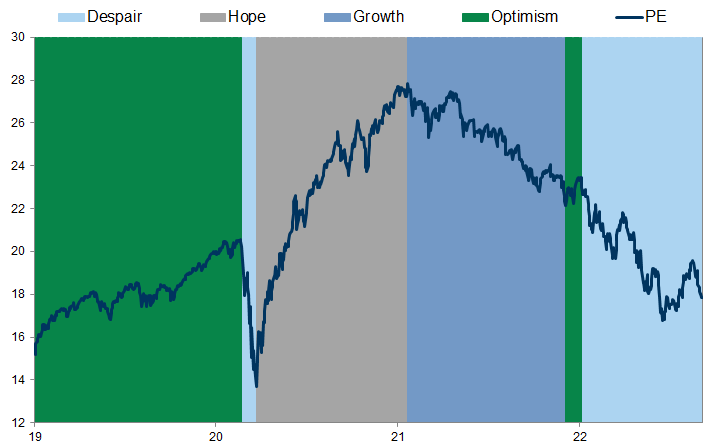

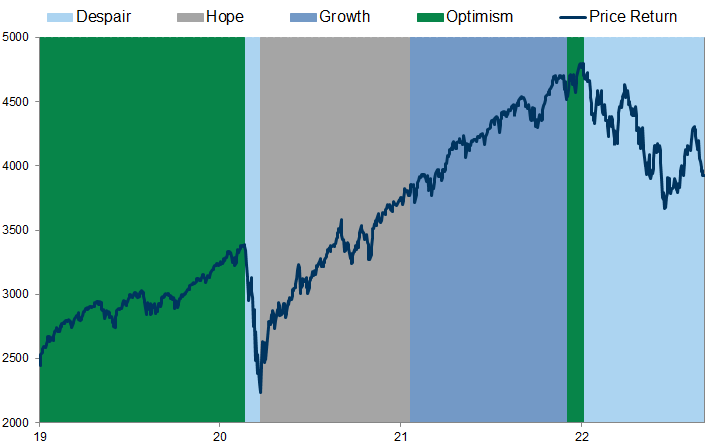

The initial transition from a bear market to a bull market tends to be strong and driven by valuation expansion, irrespective of the type of bear market.

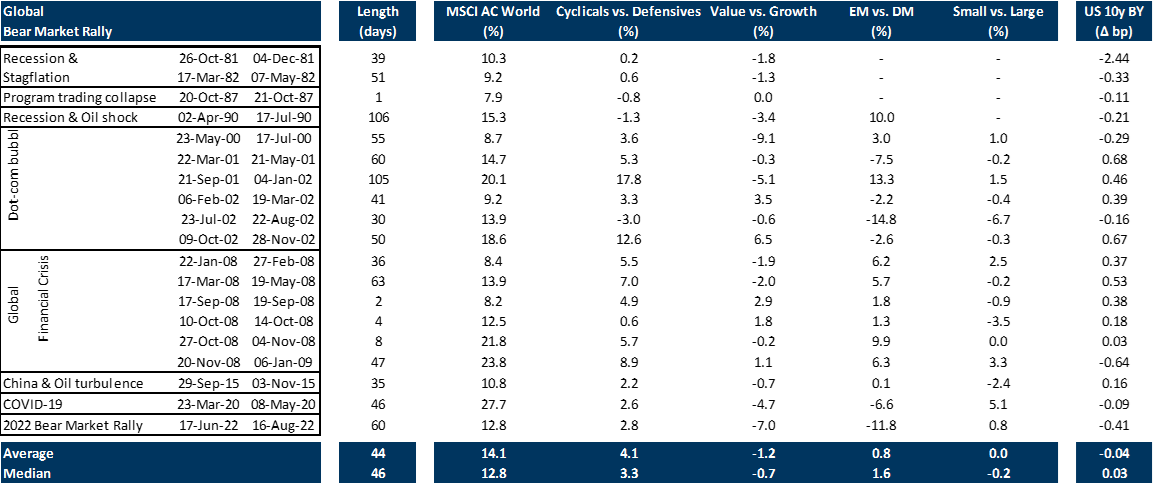

But bear market rallies are common, making these transitions difficult to spot in real time.

Low valuations are a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for a market recovery. Getting close to the worst point in the economic cycle, reaching a peak in inflation and interest rates, and negative positioning are also important.

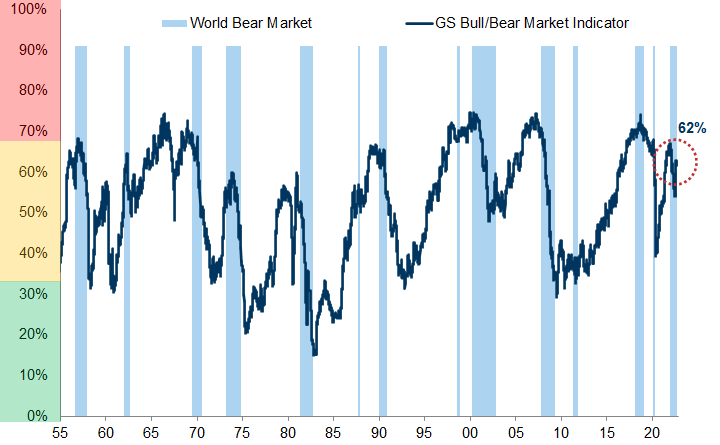

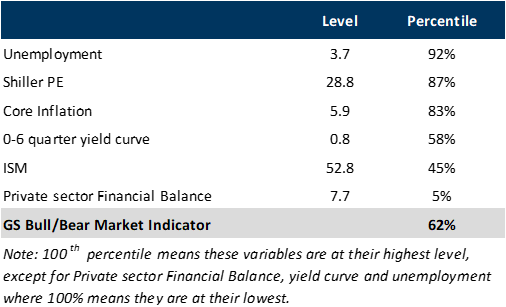

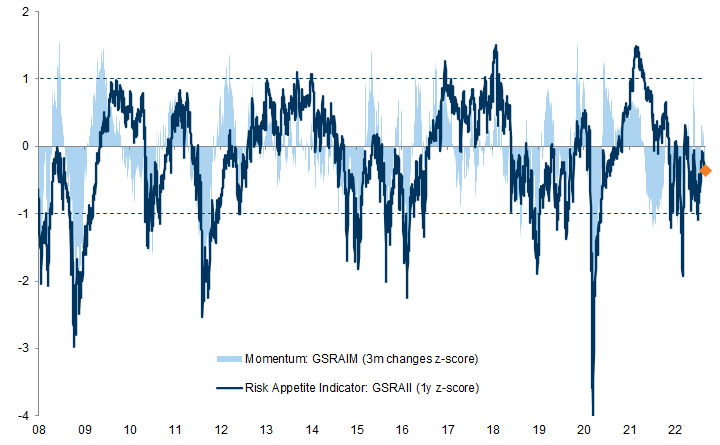

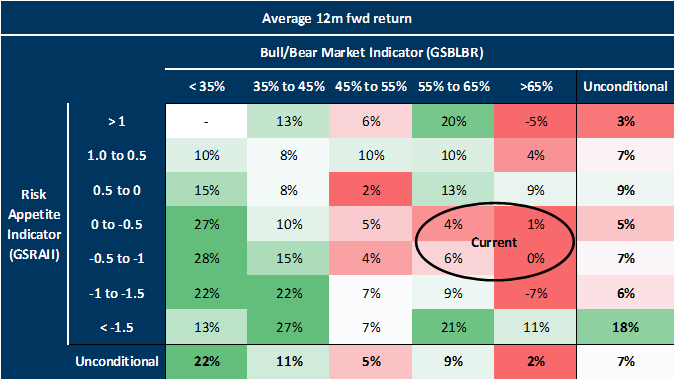

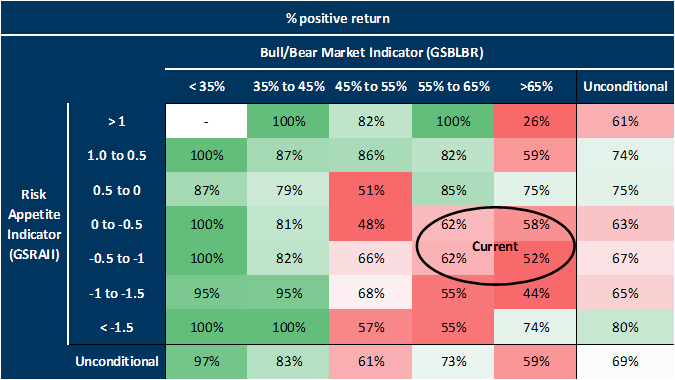

Our fundamentals-based Bull/Bear Indicator (GSBLBR) and our sentiment-based Risk Appetite Indicator (GSRAII) help identify potential inflection points. Combining these can provide powerful signals when they are both close to extremes.

We have not yet met these conditions, suggesting further bumpy markets before a decisive trough is established.

We expect the next bull market to be 'Fatter & Flatter' than the last; this 'Post-Modern Cycle' is also likely to be driven by some distinct themes with a greater focus on margin sustainability.

Summary

Lower aggregate returns; a Fat & Flat rather than a secular bull market.

More focus on Alpha than Beta.

A greater reward for diversification and buying at attractive valuations.

Investment to increase corporate efficiency (energy efficiency and labour productivity).

Bear market profiles

Structural bear market - triggered by structural imbalances and financial bubbles. Very often there is a 'price' shock such as deflation and a banking crisis that follows.

Cyclical bear markets - typically triggered by rising interest rates, impending recessions and falls in profits. They are a function of the economic cycle.

Event-driven bear markets - triggered by a one-off 'shock' that either does not lead to a domestic recession or temporarily knocks a cycle off course. Common triggers are wars, an oil price shock, EM crisis or technical market dislocations. The principal driver of the bear market is higher risk premia rather than a rise in interest rates at the outset.

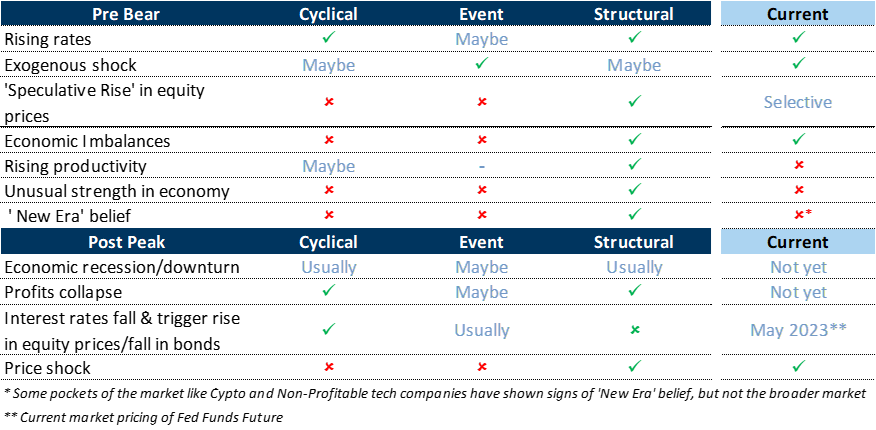

How do you know if you are in a Cyclical or Structural downturn?

Excessive price appreciation & extreme valuations

New valuation approaches justified

Increased market concentration

Frantic speculation and investor flows

Easy credit, low rates & rising leverage

Booming corporate activity

New Era narrative and technology innovations

Late-cycle economic boom

The emergence of accounting scandals and irregularities

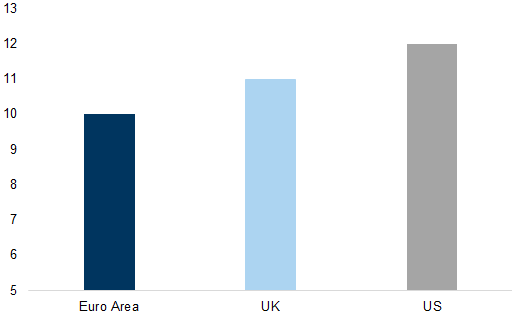

Exhibit 5: High savings rate across regions provides a buffer

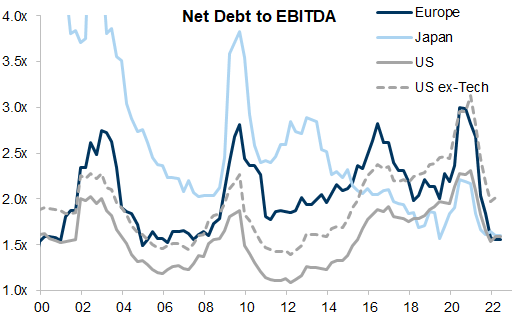

Exhibit 6: Net debt to EBITDA has decreased

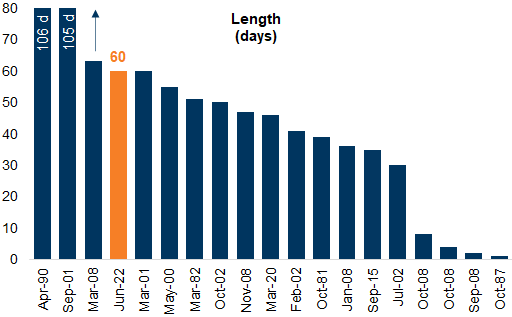

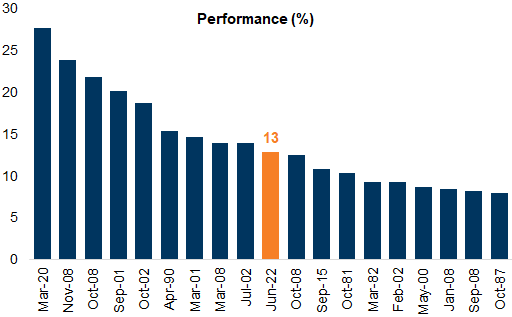

Differentiating between a Bear bounce & a new Bull market

Bear market rallies are common

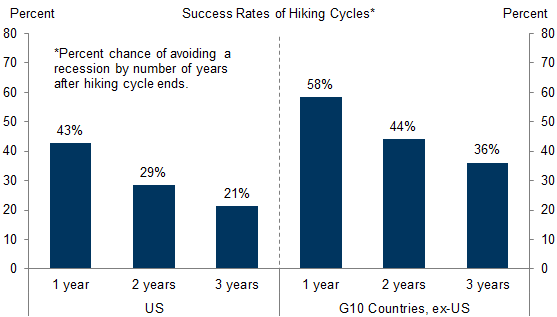

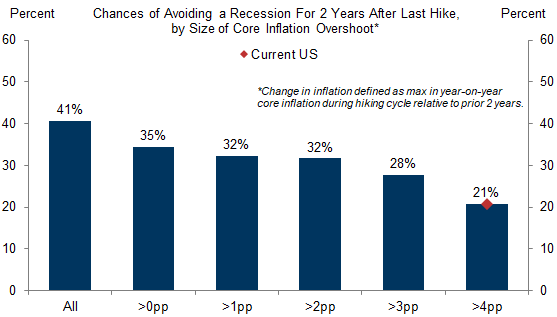

The Difference between Hard & Soft Landings

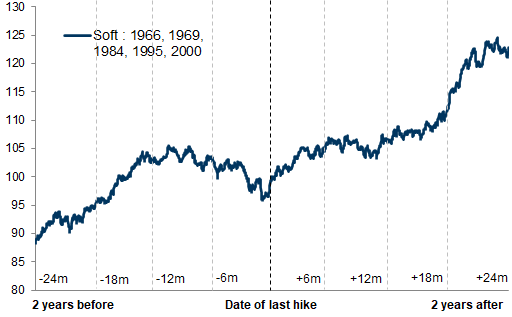

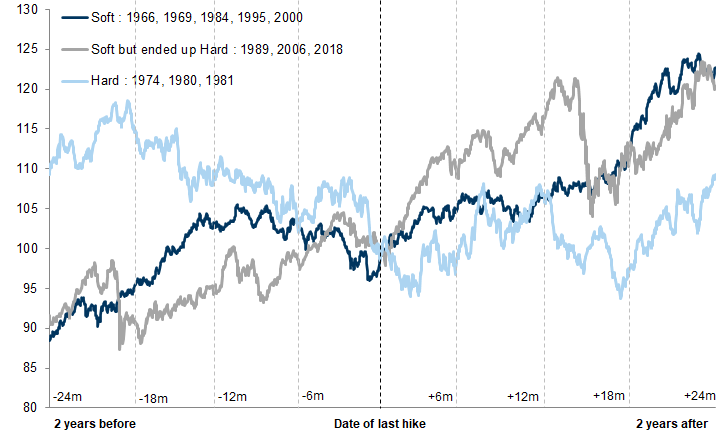

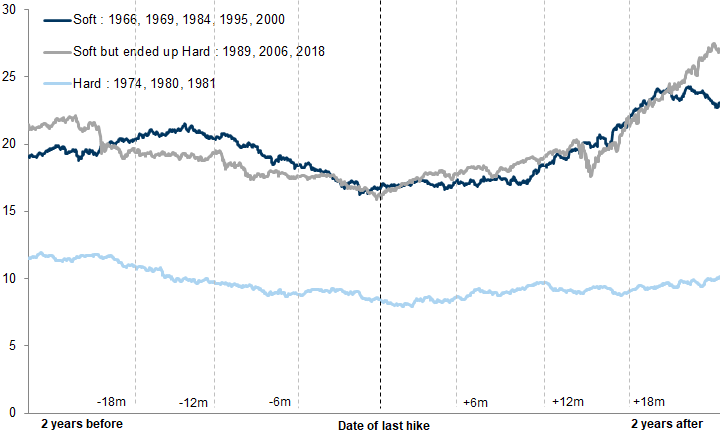

Cyclical bear markets around 'soft landings' are likely to end around the perceived peak in the policy cycle.

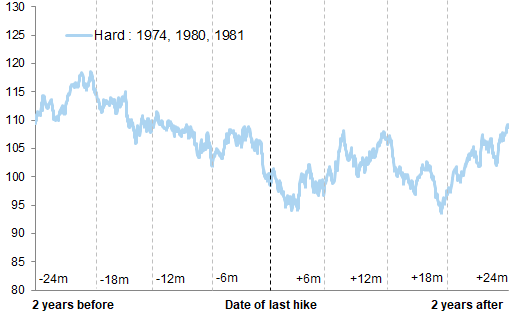

Cyclical bear markets associated with 'hard landings' are not likely to be resolved by interest rates alone. A peak in the policy cycle is an important part of the recovery puzzle, but a slowing in the second derivative of growth, together with depressed valuations, also tends to be important.

Exhibit 11: Profile of S&P 500 performance around historical soft landings

Exhibit 12: Profile of S&P 500 performance around historical hard landings

Why have we experienced a bear market rally and not a bull market inflection?

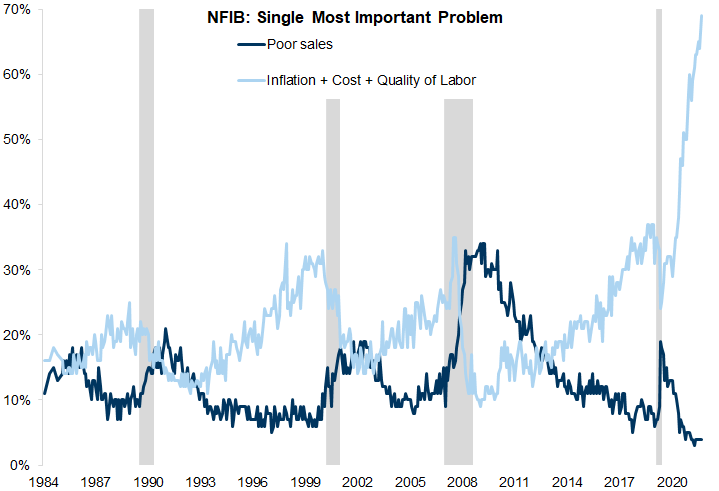

Supply as the problem, not demand

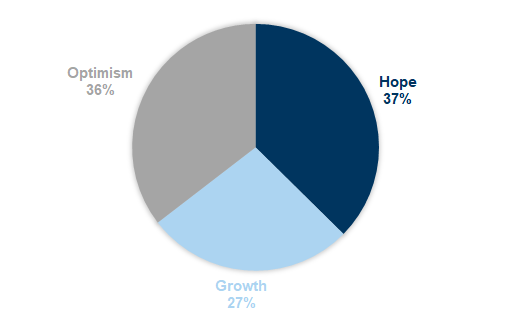

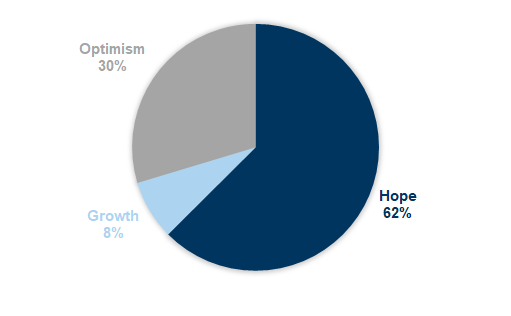

Identifying the transition from Bear Market to Bull Market

Exhibit 17: While the returns on average are fairly evenly distributed across the 3 phases of the bull market...

Exhibit 18: ...The length of these periods varies

Cheap valuations

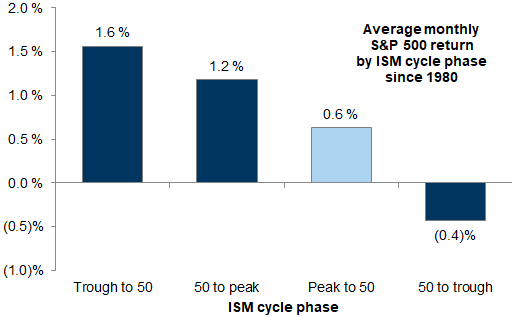

A bottoming in the rate of deterioration in economic activity

A sense that interest rates and inflation are peaking

Negative positioning

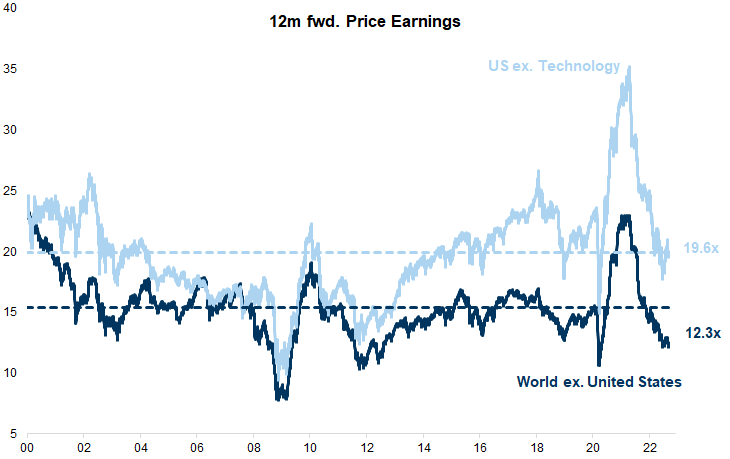

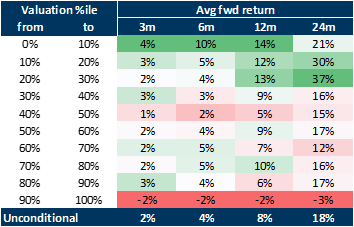

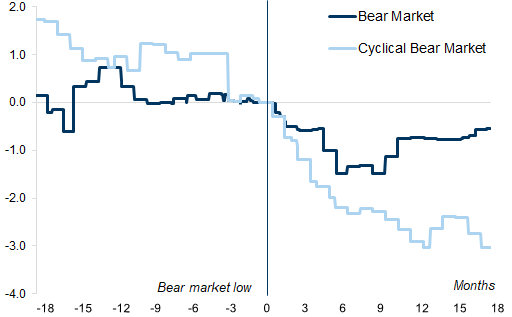

1. Valuations & the market inflection

Exhibit 19: Valuations below the 30th percentile of historical averages are associated with positive returns

Exhibit 20: Global equities do not yet look cheap

Current assessment: We are not yet at levels consistent with a market trough.

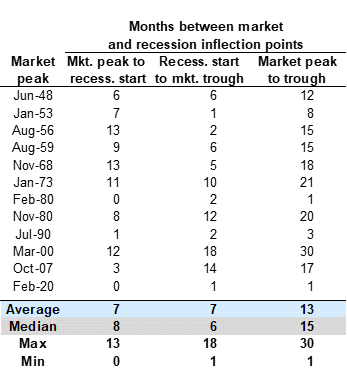

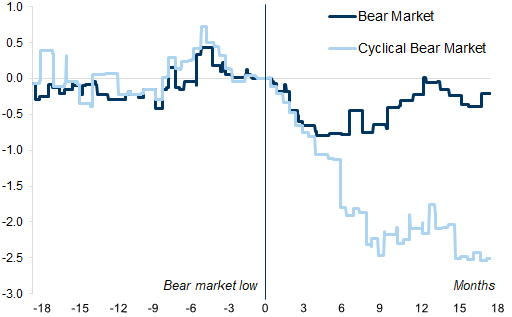

2. Growth & the market inflection

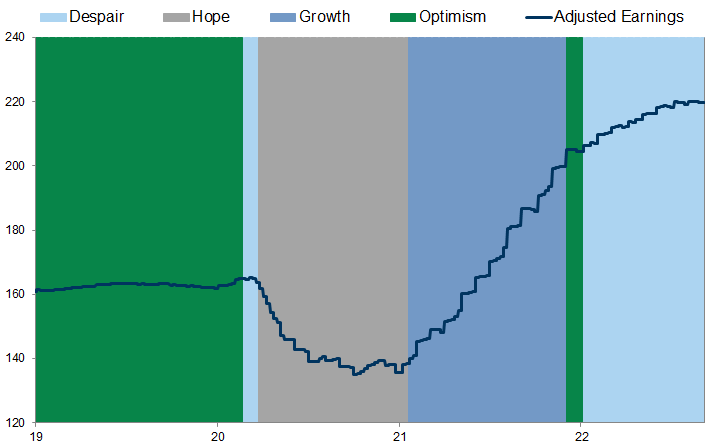

Exhibit 23: Most bear markets trough around 9 months before a recovery in corporate earnings per share

Exhibit 24: Most bear markets trough roughly 3-6 months before any trough in growth momentum

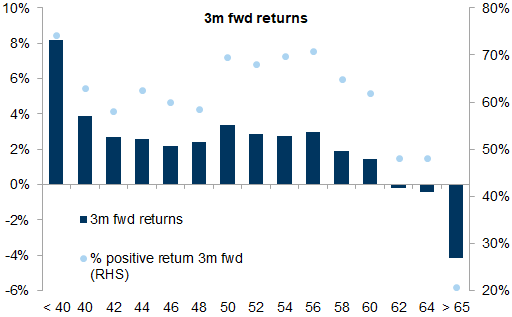

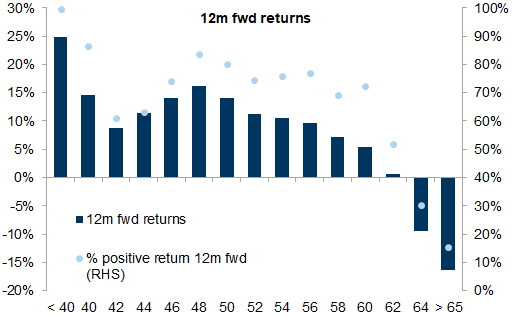

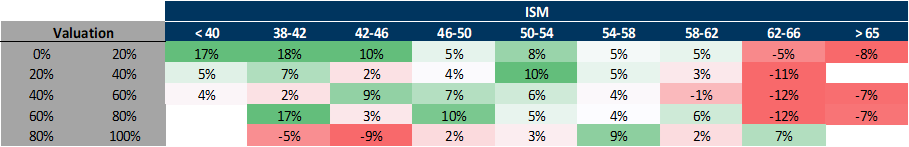

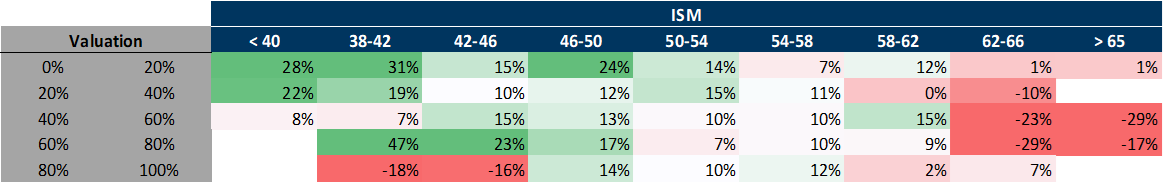

ISM <40 – strong BUY signal, you are at or very close to a trough

42-44 – DON’T BUY, we have gone below the point of no return and are now heading for recession

46-48 – provided the downturn is mild, this can be an excellent entry point, especially over 6 and 12m - BUY

50-54 – this is more or less ‘normal’ and generally ‘normal’ has been good for US equities – BUY

58 or above – SELL, the rate of growth is very likely to slow.

Exhibit 25: Significant weakness is typically followed by strong returns...

Exhibit 26: ...and significant strength by weak returns

Combining Growth and Valuation as a signal

Current assessment: We are not yet at levels consistent with a market trough.

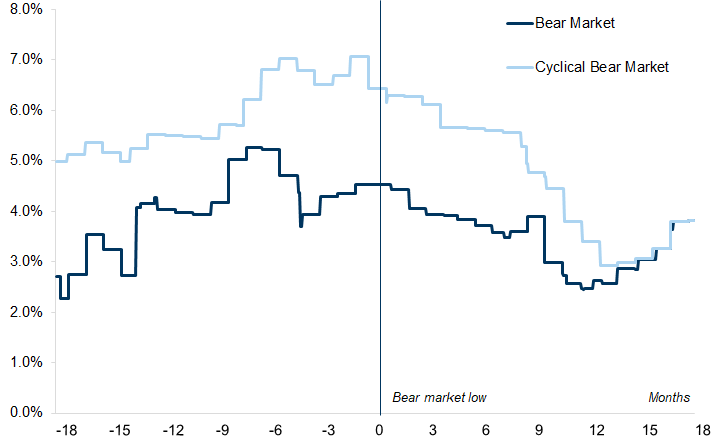

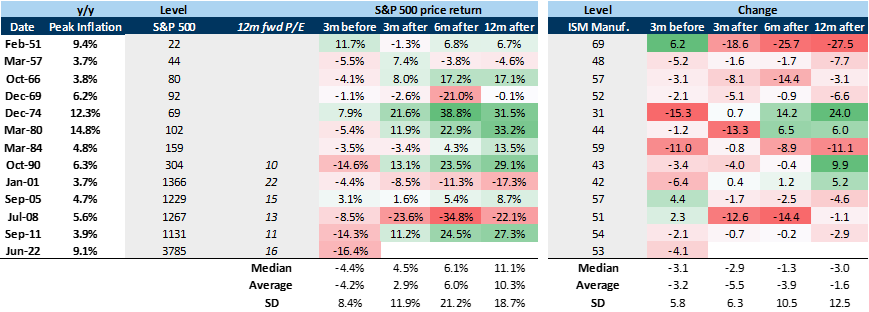

3. Inflation, interest rates & the market inflection

Exhibit 31: On average the market starts to recover just before 2-year rates start to fall...

Exhibit 32: ...and typically not until the fed funds rate has peaked

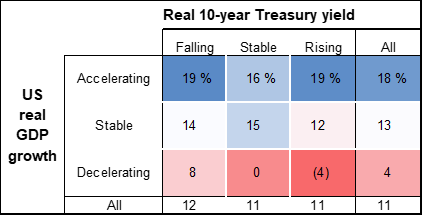

Combining Growth and Interest rates

Exhibit 33: Accelerating real GDP is associated with positive returns irrespective of the direction in real rates, while decelerating growth coupled with rising real rates is by far the worst scenario

Current assessment: We are not yet at levels consistent with a market trough.

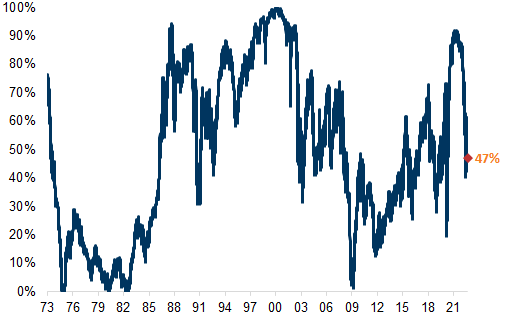

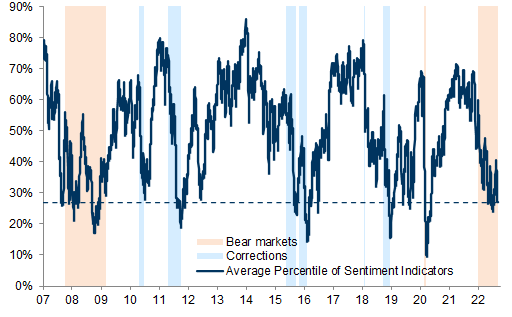

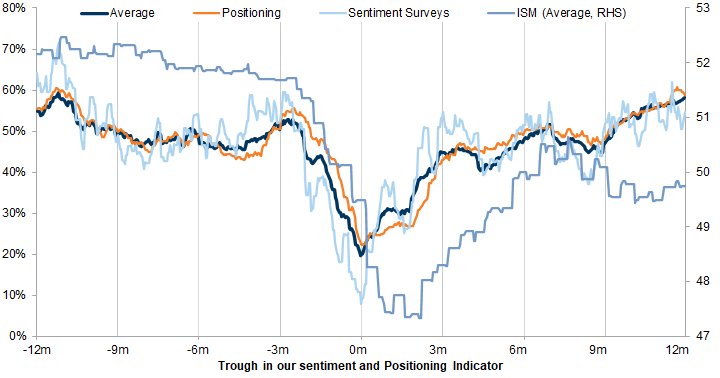

4. Investor positioning & the market inflection

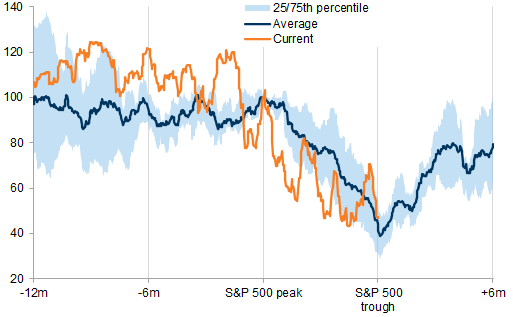

Exhibit 34: Troughs in our indicator have historically coincided with equity troughs

Exhibit 35: Prolonged bear markets can see sharp reversals in positioning before a sustained rebound

Current assessment: We are not yet at levels consistent with a market trough.

Aggregate indicators to guide investors at inflection points

Our fundamentals indicator, GSBLBR

Our Risk Appetite Indicator (GSRAII)

Equities (all for MSCI World): ERP, EM vs. DM, Cyclicals vs. Defensives, Small vs. Large, Financials vs. Staples, S&P 500 vs. low volatility stocks.

Equity volatility: VIX, VSTOXX, CBOE skew, CBOE put/call ratio (1-month average), EUREX put/call ratio (1-month average).

Credit: USD HY vs. IG spread, EUR HY vs. IG spread, EUR IG spread, USD IG spread, Spain and Italy sovereign spreads, EM USD credit spreads.

Bonds: Germany 10- and 30-year, US 10- and 30-year.

FX: JPY/AUD, CHF/GBP, EUR/USD, Gold and USD trade-weighted.

Combining our Bull/Bear Market Indicator with our Risk Appetite Indicator

Current assessment: We are not yet at levels consistent with a market trough. It is likely that the market will price a worse combination of growth and interest rates before a sustained trough in equity markets can be established.

The Post-Modern Cycle and the Leaders of the Next Bull Market

Lower aggregate returns; a Fat & Flat rather than secular bull market

More focus on Alpha than Beta

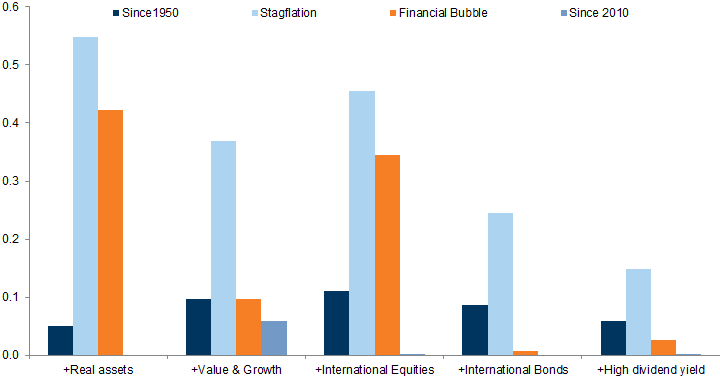

A greater reward for diversification and buying at attractive valuations

Increased investment to increase corporate efficiency

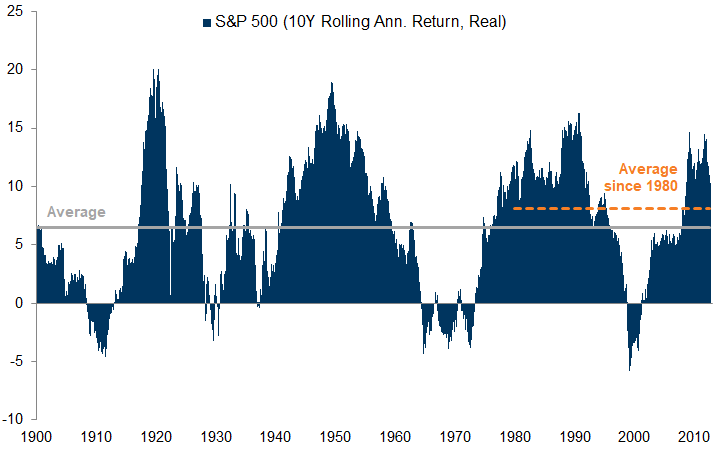

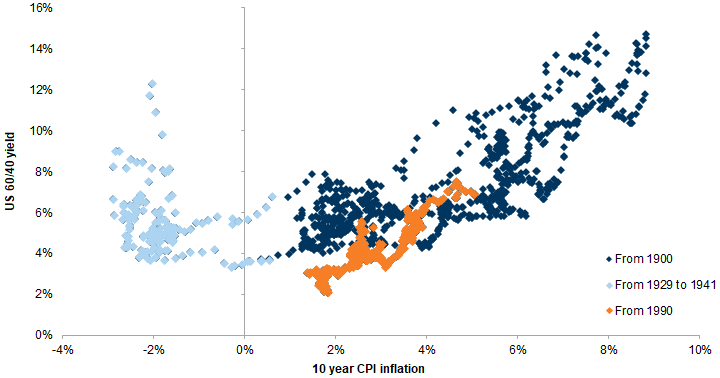

Lower Returns; Fat & Flat

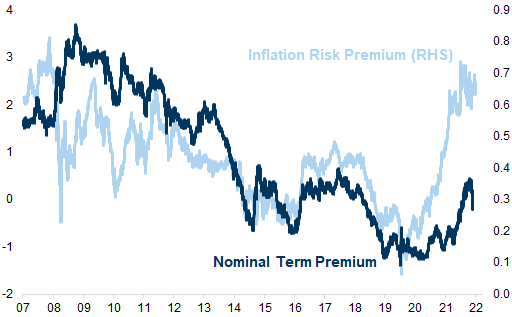

Exhibit 44: Inflation risk premia fell, as did nominal term premia

Exhibit 45: Proportion of negative-yielding global bonds

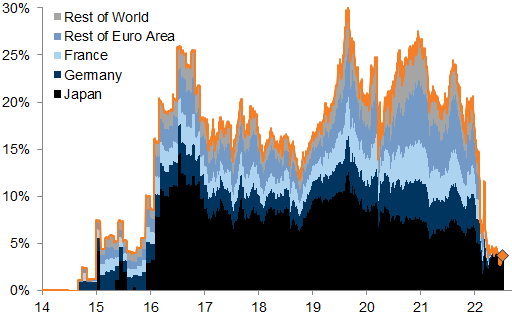

More Alpha than Beta

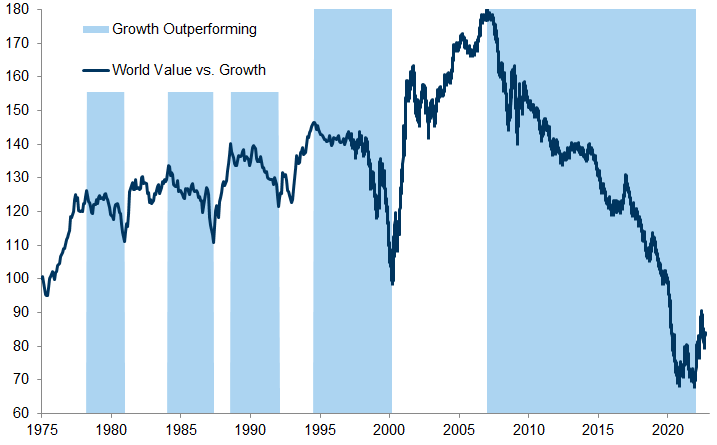

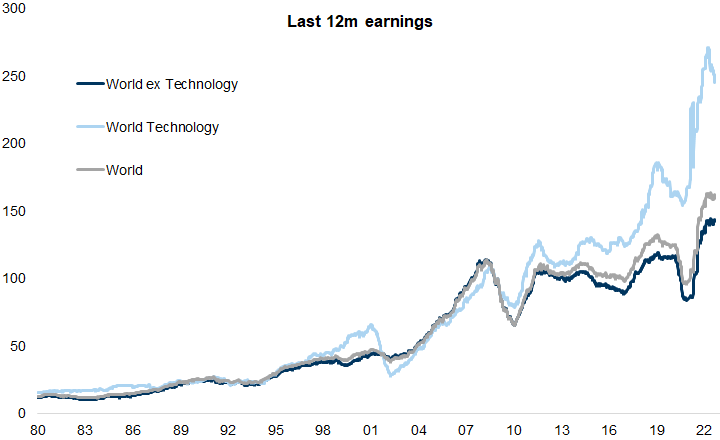

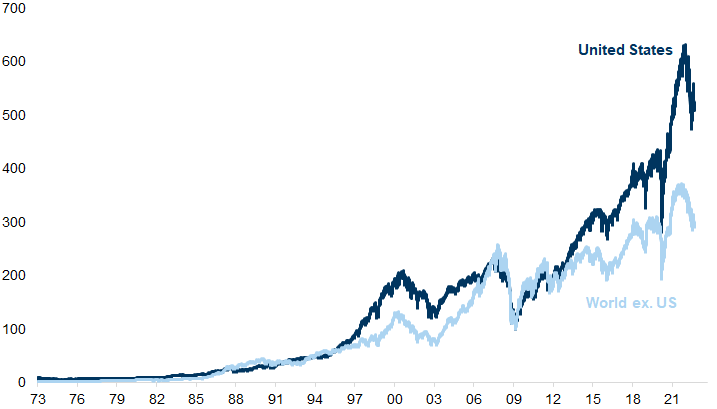

The secular decline in bond yields and inflation expectations has boosted the value of longer-duration Growth companies (while hitting Value companies most at risk of deflation).

A secular decline in long-term growth expectations, together with greater uncertainty about growth.

The bifurcation of industry returns, with impressive growth in the returns of the Technology sector and, at the same time, a secular decline in returns in sectors such as Banks and Energy.

Specific headwinds facing many value industries. For example, banks needed to de-lever and face tougher capital requirements and regulation, while commodity-related stocks suffered from falling commodity prices.

Diversification

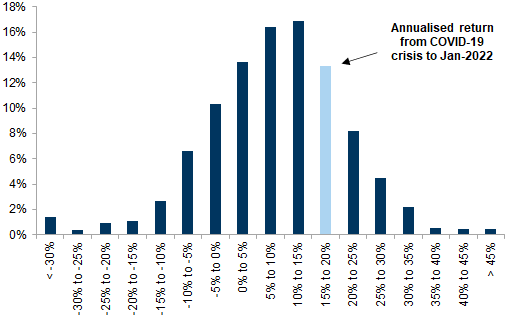

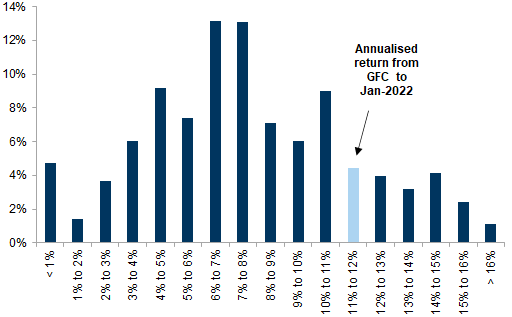

Exhibit 48: Since the COVID-19 crisis a US 60/40 portfolio has delivered strong annualised returns

Exhibit 49: Despite the COVID-19 crisis the annualised 60/40 returns since the GFC remain in the top quartile

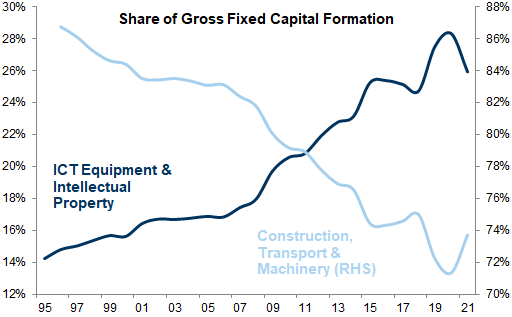

Greater Efficiency

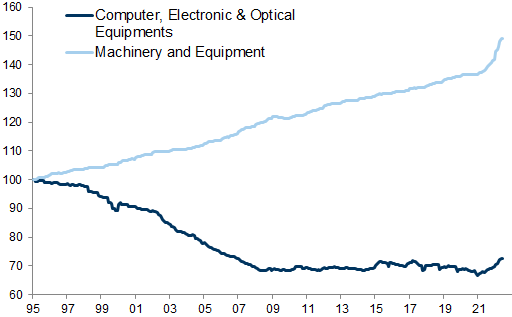

Exhibit 52: The aggregate spend on gross fixed capital has declined just as spending on ICT has increased

Exhibit 53: Deflation in technology costs and inflation in capital costs

Appendix

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.