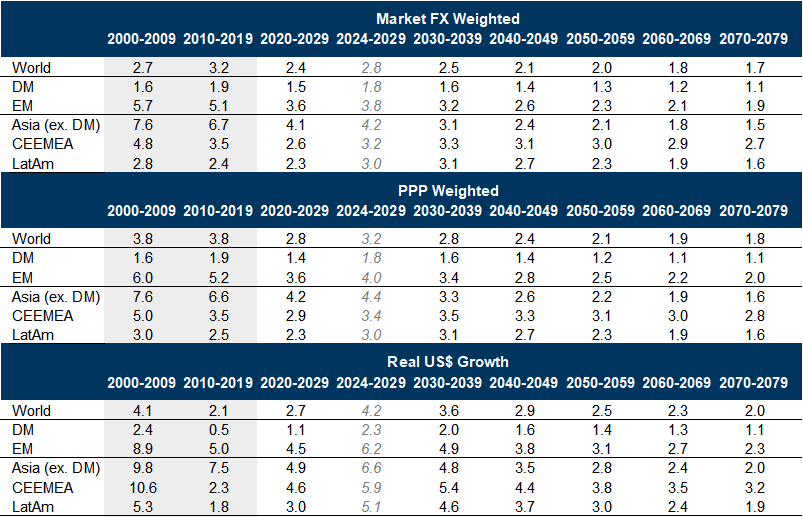

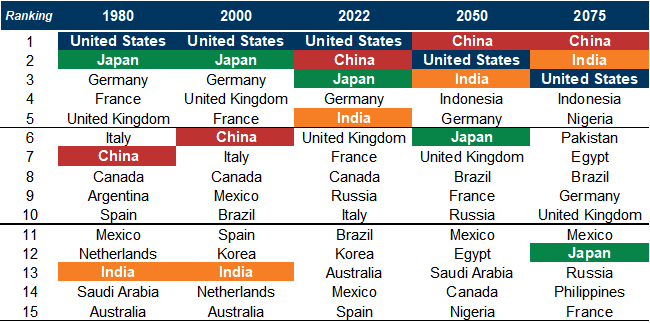

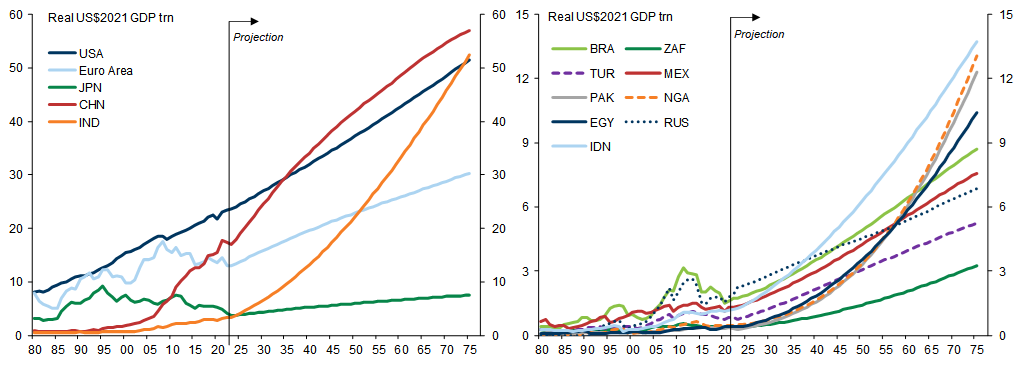

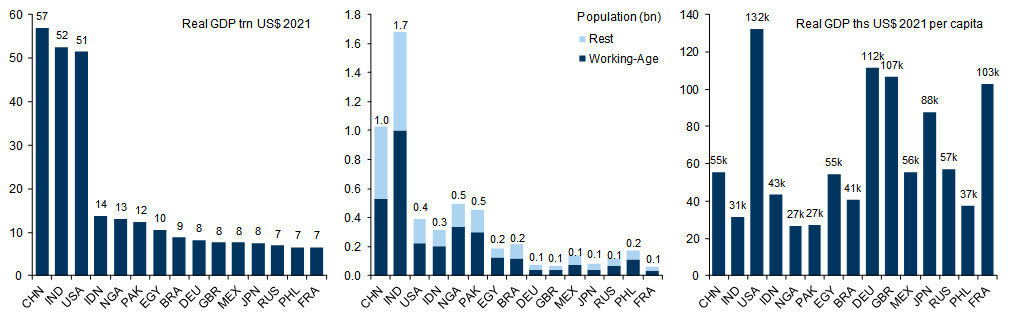

We recently set out long-term growth projections for the global economy, covering 104 countries out to the year 2075. We expect EM growth to continue to outstrip DM over the remainder of this decade (3.8% vs. 1.8%). In 2050, we project that the world's five largest economies (measured in US$) will be China, the US, India, Indonesia, and Germany. By 2075, China, the US, and India are likely to remain the three largest economies and, with the right policies and institutions, seven of the world's top ten economies are projected to be EMs.

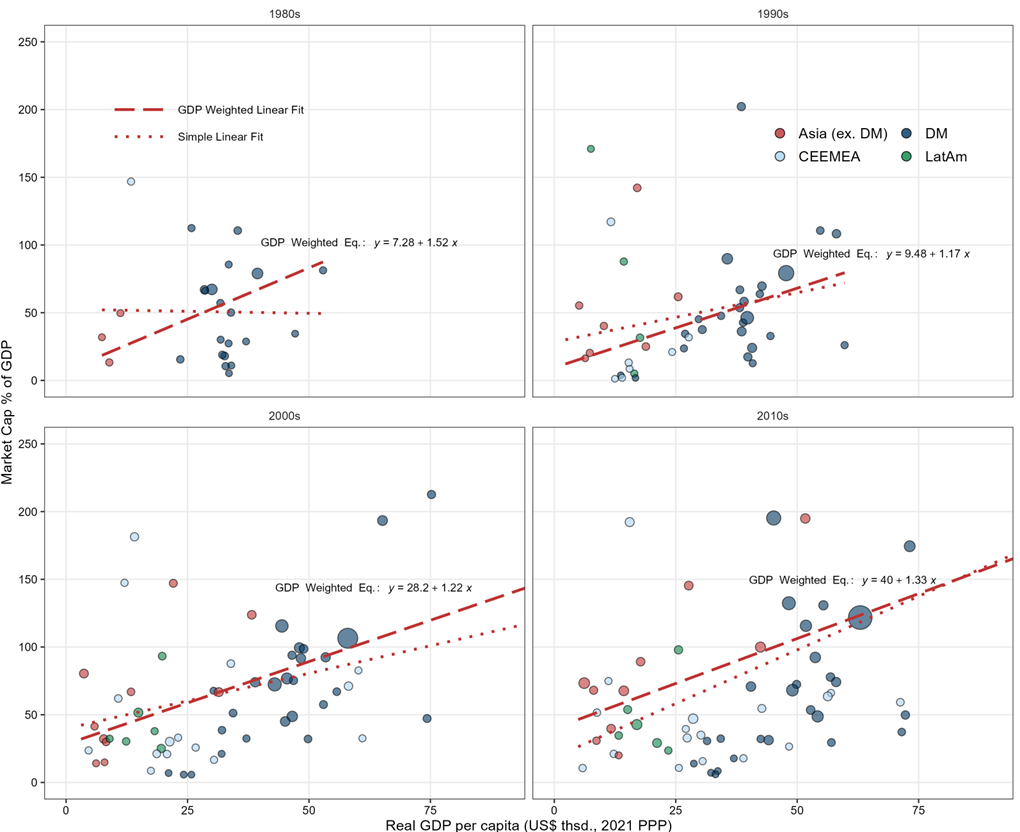

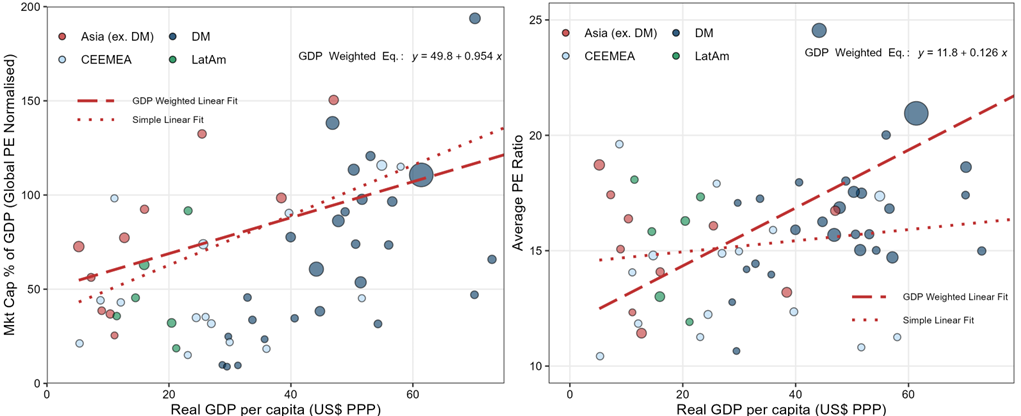

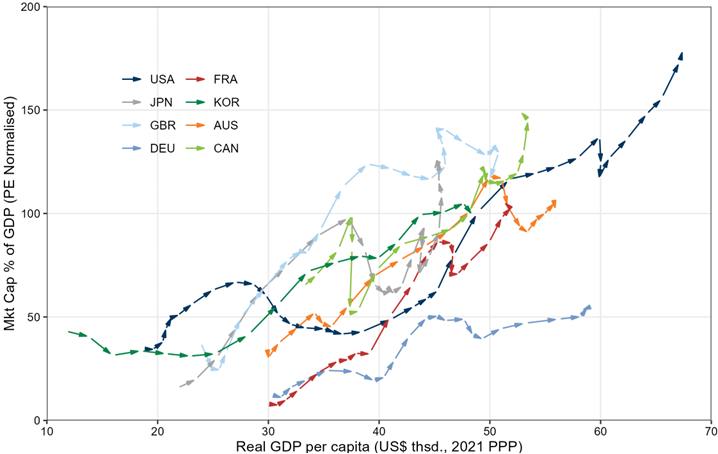

We now extend our analysis to project the future growth of global capital markets, focusing on equity market capitalisation. To convert our long-term GDP projections into estimates of future equity market capitalisation, we exploit the fact that equity market capitalisation-to-GDP ratios tend to increase with GDP per capita. Given the convergence taking place in EM GDP per capita levels, this implies that EM equity assets are likely to grow more rapidly than GDP.

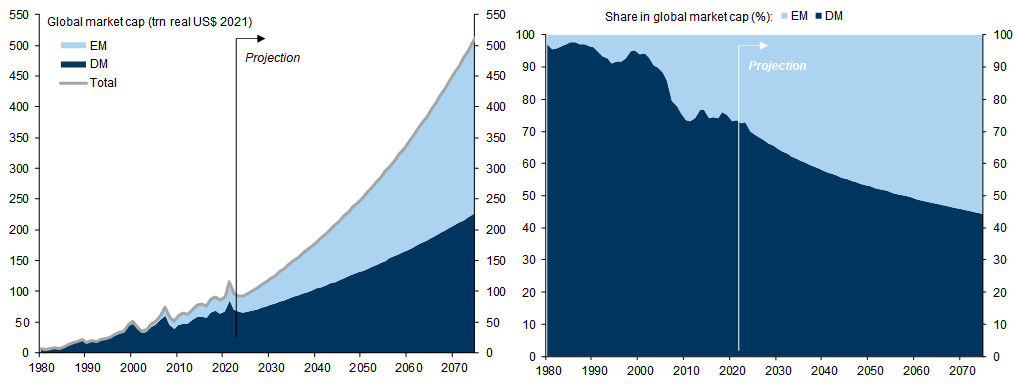

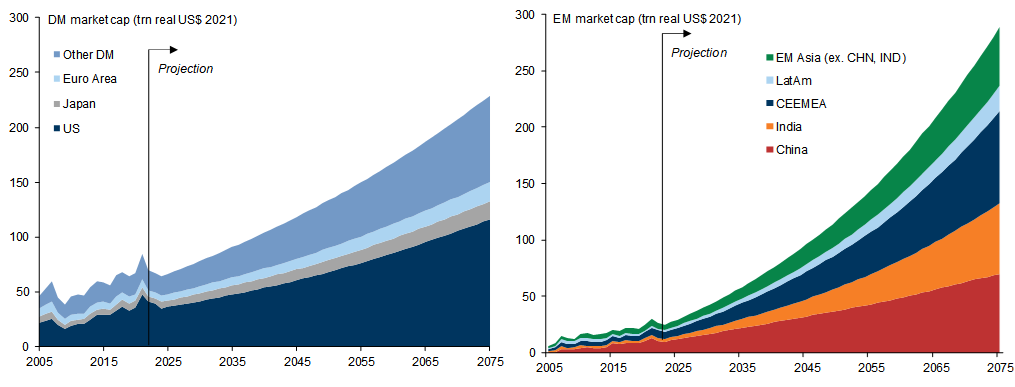

We expect EM equities to outperform DM in the longer run, due to stronger earnings growth and, as risk premia fall, multiple expansion. However, the most important dynamic underlying EM capital market growth in our projections is the equitisation of corporate assets, the deepening of capital markets, and the disintermediation that takes place as financial development proceeds (processes that do not, by themselves, imply EM equity outperformance).

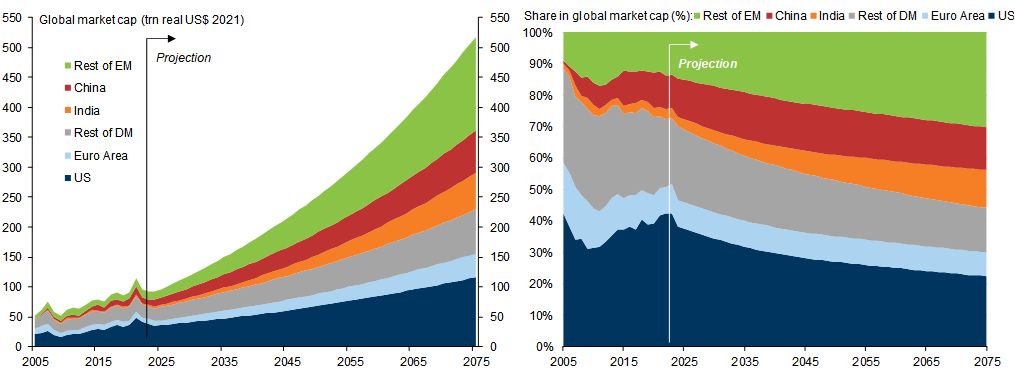

Our projections imply that EMs' share of global equity market capitalisation will rise from around 27% currently to 35% in 2030, 47% in 2050, and 55% in 2075. We expect India to record the largest increase in global market cap share – from a little under 3% in 2022 to 8% in 2050, and 12% in 2075 – reflecting a favourable demographic outlook and rapid GDP per capita growth. We project that China’s share will rise from 10% to 15% by 2050 but, reflecting a demographic-led slowdown in potential growth, that it will then decline to around 13% by 2075. The increasing importance of equity markets outside the US implies that its share is projected to fall from 42% in 2022 to 27% in 2050, and 22% in 2075.

Openness to trade and capital flows is a necessary condition for the successful development of capital markets. Of the many risks to our projections, we view the possibility that populist nationalism leads to increased protectionism and a reversal of globalisation as the most significant.

The Path to 2075 — Capital Market Size and Opportunity

Our Long-Term Projections — The Rising Importance of Major EMs

First, there is a large gap between the largest three economies (China, India, and the US) and all other economies (although the Euro area represents a fourth economic superpower if it is treated as a single economy). Thus, although Indonesia, Nigeria and Pakistan are projected to be placed fourth, fifth, and sixth in the 2075 GDP rankings, each is projected to be less than one-third of the size of China, India, and the US.

Second, while China and India are projected to be larger than the US by 2075, our projections imply that the US will remain more than twice as rich as both (and five times as rich as countries such as Nigeria and Pakistan). This reflects the relatively conservative assumptions on income convergence that we have factored into our projections and underlies the importance of demographic differences in driving the projected ordering of country size in 50 years' time.

Projecting Capital Market Size

Exhibit 6: Richer Economies Typically Have More Equitised Capital Markets and Higher Equity Valuations

Capital Market Size and Opportunity: Growing Importance of EM, With High Potential in India

Equity Market Growth ≠ Equity Market Outperformance

Key Long-Term Risk to Capital Markets Growth — The Rise of Populist Nationalism

Appendix

Data Sourcing

Adjusting EMC Ratios for Short-Term Fluctuations in Valuation

- 1 ^ “The Path to 2075 — Slower Global Growth, But Convergence Remains Intact”, Global Economics Paper, 6 December 2022.

- 2 ^ Given the recent pessimism around China's long-term growth prospects, some readers may be surprised that we expect China to overtake the US at this horizon. However, three points are worth bearing in mind in this regard: First, China has already closed most of the gap with US GDP (China's GDP has risen from 12% of the US in 2000 to around 80% currently). Second, despite significant downward revisions, potential growth in China remains significantly higher than the US on our revised estimates (4.0% vs. 1.9% for 2024-29). Third, in addition to differences in potential growth, we expect some of the US Dollar’s real overvaluation vs. the Chinese Yuan to be unwound over the next 10-15 years.

- 3 ^ For our projections, we assume that EM economies are a fixed group – i.e., they do not become re-classified as DM economies as they become more developed.

- 4 ^ The most important source of forecast uncertainty over longer horizons is productivity growth because errors in forecasting productivity trends tend to accumulate over time, whereas cyclical fluctuations tend to be mean-reverting.

- 5 ^ We focus on equity market capitalisation as, in contrast to debt capital markets and banking sector development, it is relatively straightforward to measure on a like-for-like basis across many countries. In practice, stock market development is also closely correlated with debt capital markets and banking sector development (see “Stock Markets, Corporate Finance and Economic Growth: An Overview”, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine, World Bank Economic Review, 1996). One consequence of focusing on each country’s equity market capitalisation is that we exclude the value of foreign direct investment (FDI). However, we view this as a positive feature because, while FDI plays a key role in economic development, it does not directly contribute to the development of domestic capital markets.

- 6 ^ See “The BRICS and Global Markets: Crude, Cars and Capital”, Global Economics Paper, 14 October 2004 and “EM Equity in Two Decades – Refreshed”, GOAL – Global Strategy Paper, 15 March 2013.

- 7 ^ By comparing decadal averages for P/E ratios and GDP per capita ratios, we effectively control for the effects of cyclical and other temporary fluctuations in P/E ratios that might otherwise distort this relationship.

- 8 ^ Exchange rate developments are a separate factor driving the US$ value of equity markets over time. However, our economic projections are already converted to real US$ values, using exchange rates that assume convergence towards PPP equilibrium rates as economies grow richer.

- 9 ^ In our 2004 projections for the BRICs economies, it was assumed either that equity market capitalisation-to-GDP ratios remain fixed at current levels or that they would converge over time to the same level. In our 2013 projections for EM economies, equity market capitalisation ratios were modelled as a non-linear function of GDP per capita levels.

- 10 ^ “EM Long-Term Growth and Equity Earnings – Stronger Growth, (Somewhat) Better Earnings”, EM Macro Themes, 25 May 2019.

- 11 ^ “The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth”, Global Economics Analyst, 26 March 2023.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.