We wrote the first paper on Women Hold Up Half the Sky in 2008, stating at the time that the old Chinese proverb was more aspiration than fact. In developed and developing countries alike, gender gaps persist in education, health, work, wages and political participation.

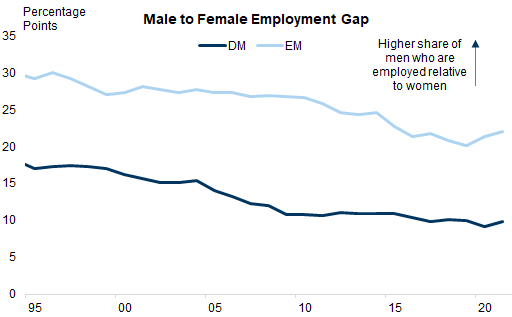

Looking at these issues afresh, we find that shrinking working age populations mean that it is now more important than ever to utilise the full resources women have to offer (and to reward them fully). We estimate that even just halving the pay and employment gap between men and women could raise the level of GDP across DM and EM by between 5% and 6%.

We have seen plenty of progress over the past 15 years – especially with respect to education and labour force participation – but we also see persistent gaps. Despite recording stellar GDP growth, India, which already had low female labour force participation, has seen it fall further. Japan and Korea have seen their pay gaps fall, but these gaps remain notably higher than elsewhere.

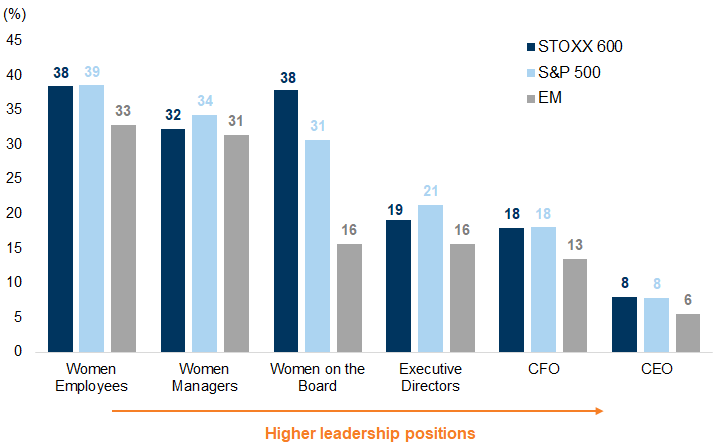

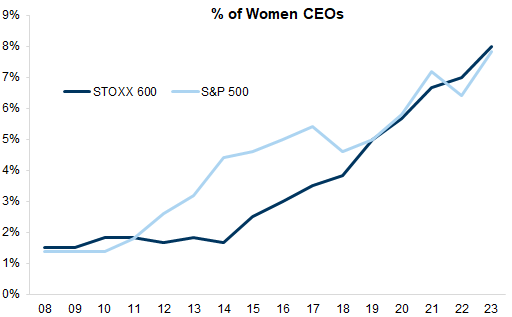

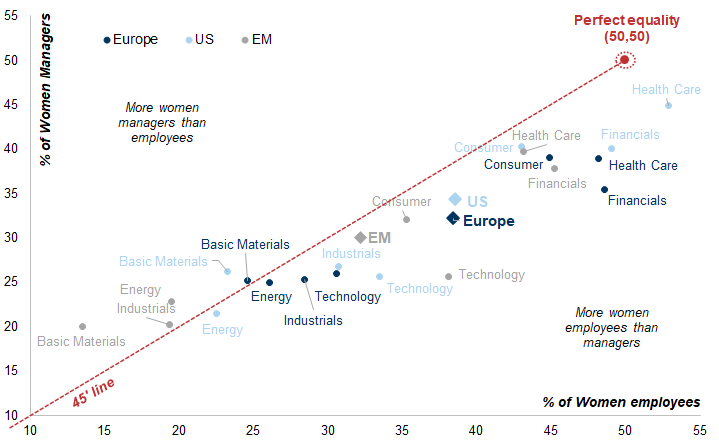

Women are moving into positions of leadership in politics and business. But, as with much of the recent progress, it is slow, and representation at the very top remains elusive. Men account for 92% of CEOs in large-cap listed DM companies and 94% in EM-listed companies.

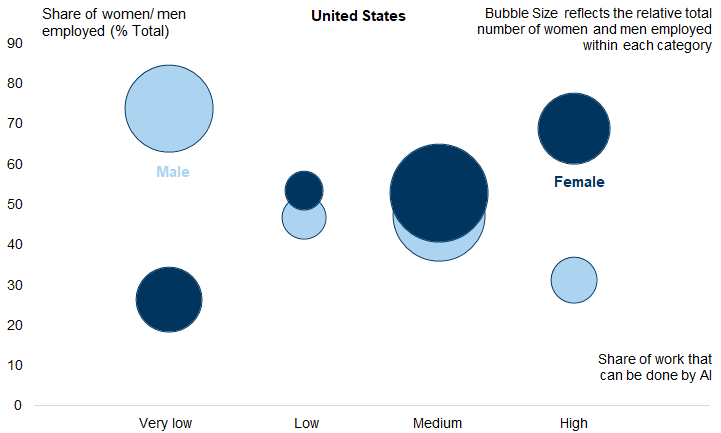

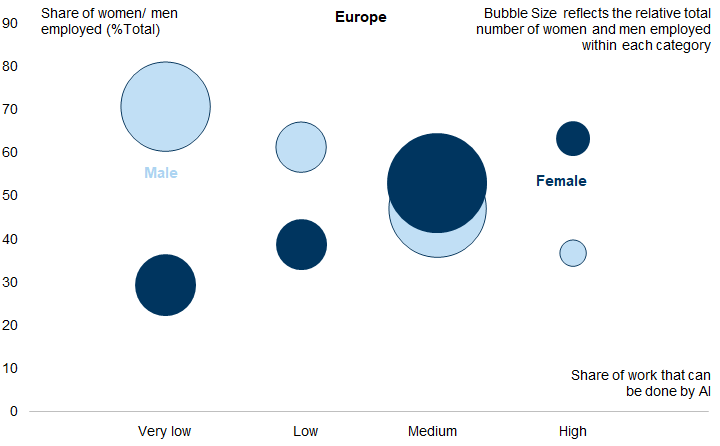

New challenges have emerged as well. The jobs that our economists assume will be most impacted by AI also tend to be held by women rather than men: ~60-70% of the workforce in these areas are women. That said, roles that require a high degree of face-to-face interaction, or caring professions – both areas where women dominate – are likely to be made more productive via AI and are unlikely to be supplanted by it.

Gender equality becoming more pivotal

1. Ageing Demographics

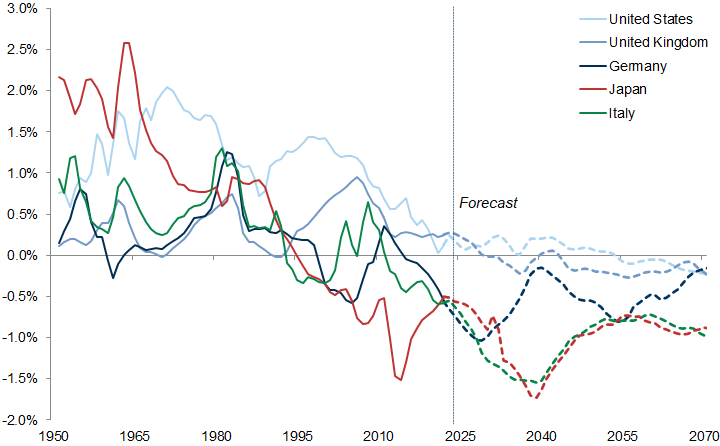

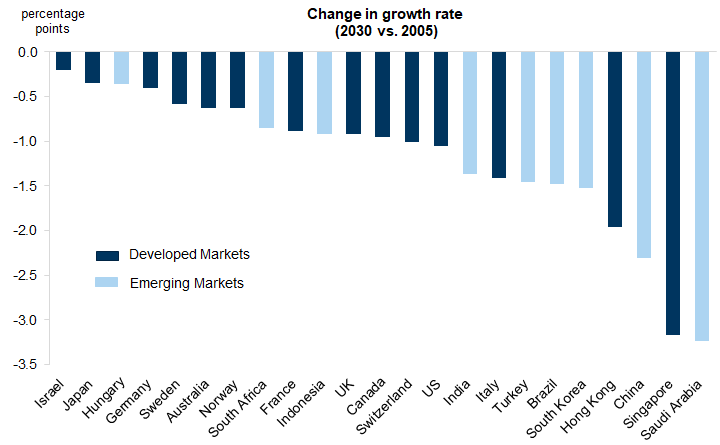

Exhibit 1: Working age population growth is declining in developed markets...

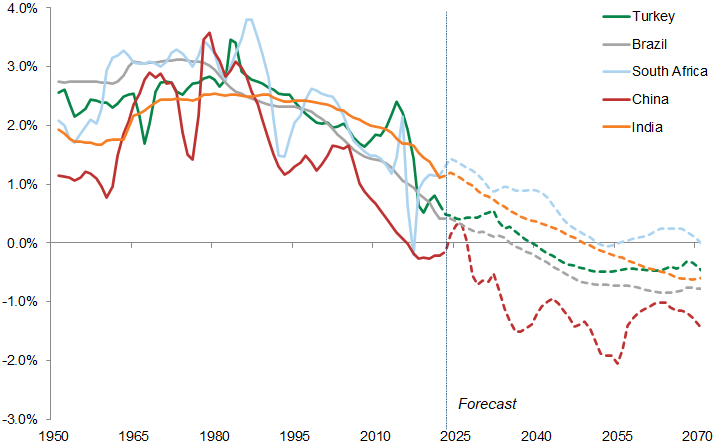

Exhibit 2: ...and in many emerging markets

Geopolitical risks – and, as a result, public policy – are increasingly pushing companies towards home-production just at a time when WAPs are declining and wage demands increasing. The US IRA and the recent European Green Deal both have an element of local sourcing of supply chains.

In addition, many developed markets have a pension funding problem exacerbated by the decline in the workforce and the increased dependency ratio.

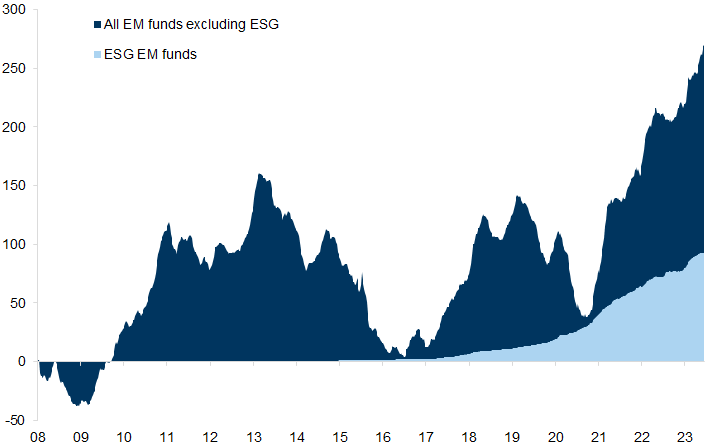

2. ESG funds are growing

Exhibit 5: Countries that do well on gender equality tend to do well on other ESG metrics

Women's equality and its progress

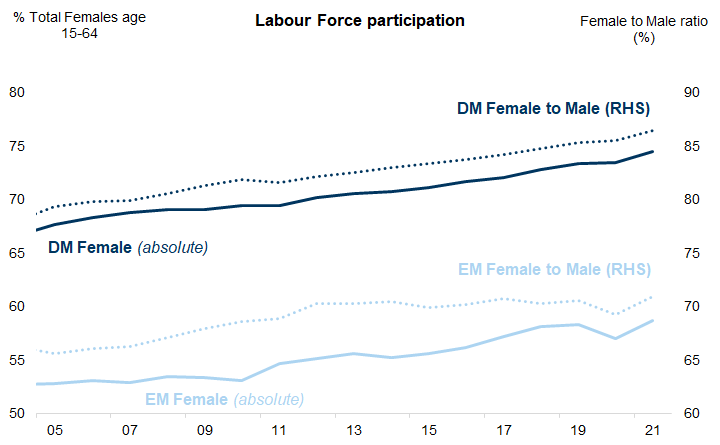

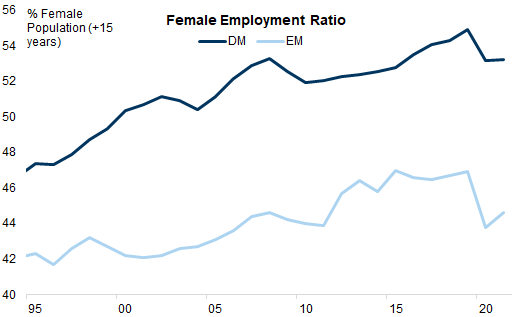

Female labour force participation is on the rise

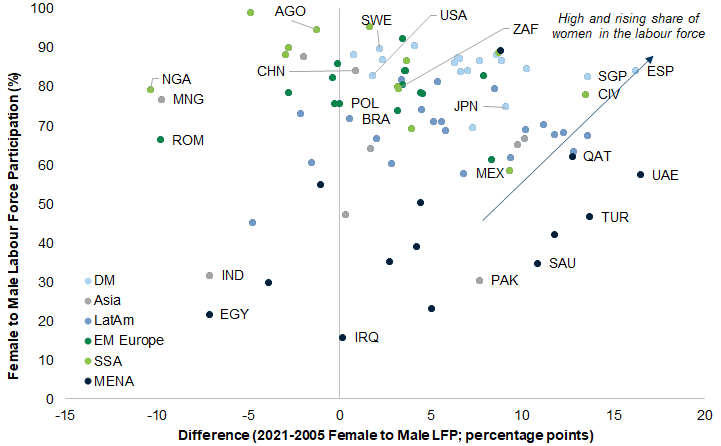

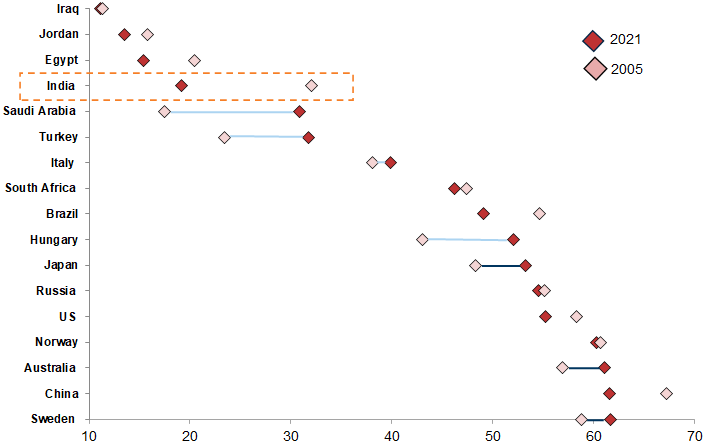

Exhibit 6: The female labour force participation rate has inceased across DM and EM over the last 15 years

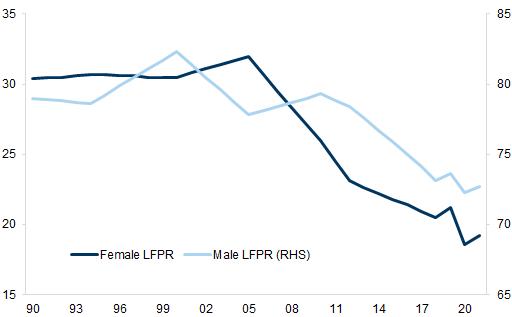

India: Female labour force participation has fallen despite rising GDP

Exhibit 11: The decline in women's LFPR has been greater than that of the male LFPR, and from a lower level than for men

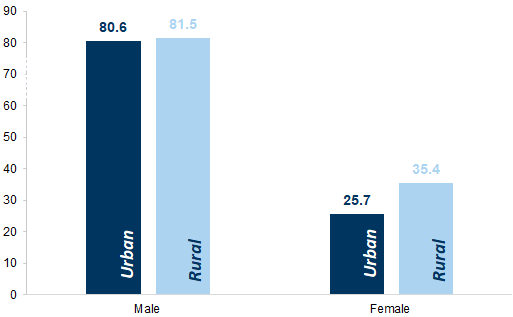

Exhibit 12: In rural India, women's LFPR is slightly higher than the urban counterpart

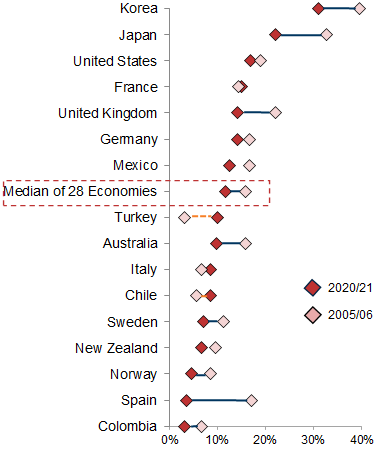

Gender pay gaps have edged lower across many countries

Exhibit 13: The median gender pay gap has come down over the last 15 years

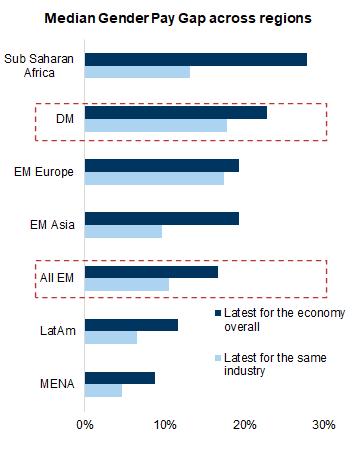

Exhibit 14: EM has a lower gender pay gap than DM

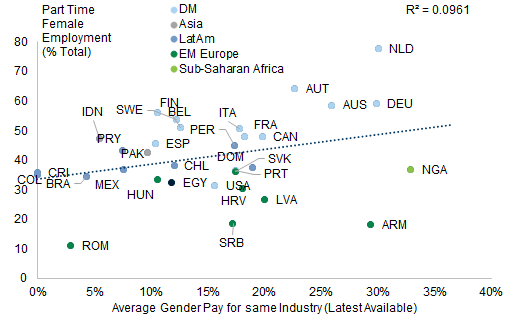

Exhibit 15: The higher propensity for part-time work in DM explains some, but not all, of the variation in gender pay gaps relative to EM

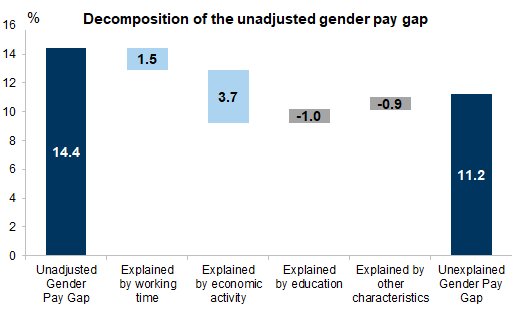

Exhibit 16: The adjusted gender pay gap remains largely unexplained (in Europe)

The economic case for equality

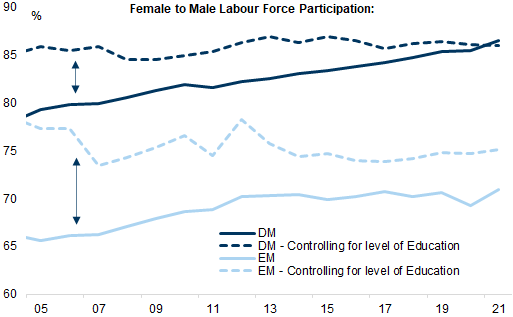

Drivers of the improvement in female labour force participation

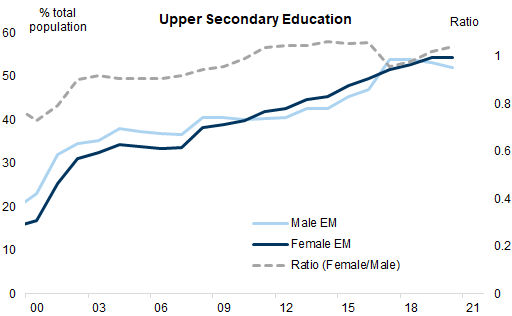

Women's Education

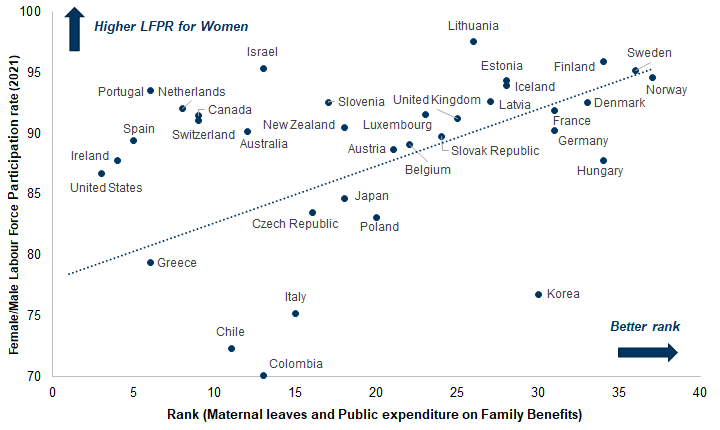

Family-friendly policies

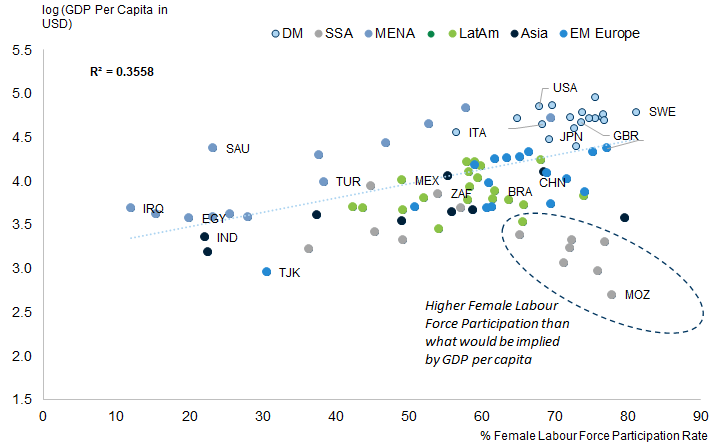

Economic development of the country

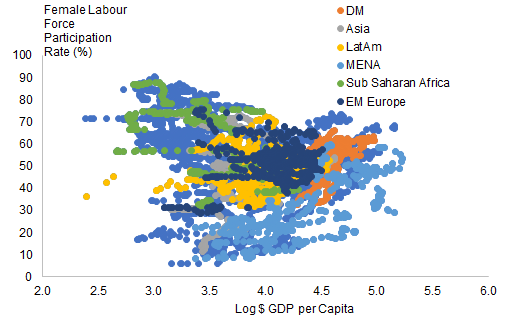

A U-Shaped Relationship between Female Labour Force Participation and Economic Development?

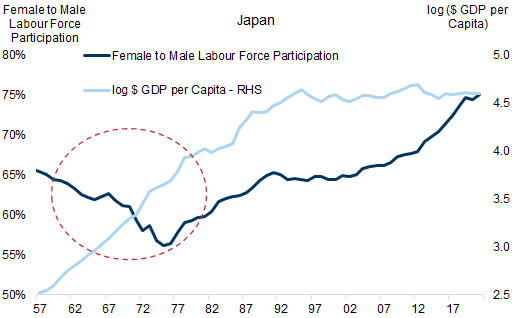

Exhibit 21: Japan initially saw a drop in the female labour force participation before it rose again

Exhibit 22: Is the relationship between female labour force participation and GDP per capita U-shaped?

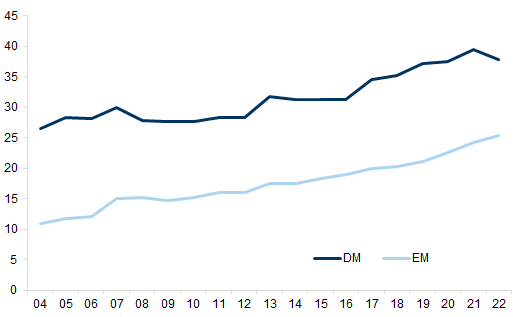

Women in leadership: Improving (slowly)

Exhibit 23: There are more women in parliament in DM and EM countries

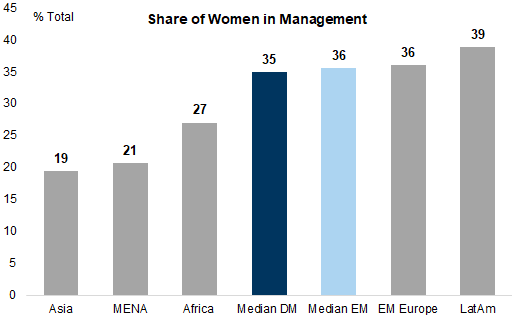

Exhibit 24: Women now make up about a third of company managers in many regions, although the Middle East and Asia lag behind

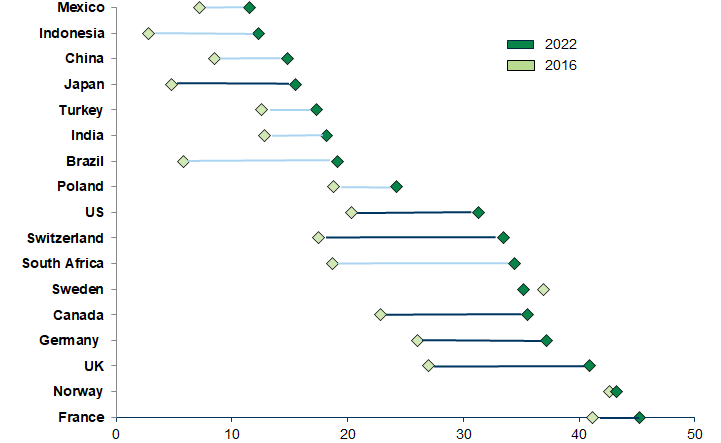

Exhibit 25: Almost every country has seen women’s representation on company boards rise

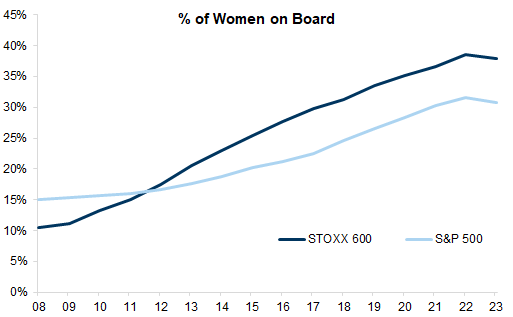

Exhibit 27: Focus on WoB in Europe has meant an outsized representation of women at that level

Exhibit 28: Just 1% of Europe/US CEOs were women in 2008 compared with around 8% now

Women under-represented in high-paying industries

Exhibit 29: We find in every sector that women are under-represented at the management level

Women and AI: More impact, but more potential to gain

Women are under-represented in the development of AI...

....and potentially by biases in the data

Women are more likely to be more affected by a changing jobs market

Exhibit 30: Jobs most likely to be impacted by AI tend to employ more women relative to men in the US...

What can policy-makers, corporates and investors do?

Education is all-important. As we show earlier in the report, female participation hasn't risen when adjusted for the level of education. It is women with a higher level of education who are both more likely to work and more likely to earn more when they are employed (and who typically spend this increased income on their families, enhancing their children's educational attainment, health and welfare, and providing a secondary boost to growth).

Family-friendly policies, including maternity and paternity leave, as well as subsidised (and good quality) childcare. All these policies are associated, albeit loosely, with higher female labour force participation.

Pay gaps, which are still large and still largely unexplained. The UK requires pay gap disclosures, and we think more transparency is often times helpful. The UK pay gap has fallen more than in most other DMs (albeit from a higher starting point) and research suggests that some of this may be accounted for by the pressure from disclosure. However, we recognise that at least some of the pay gap is down to different choices by men/women in terms of the type of jobs done and/or total hours worked. Again, it is equality of opportunity that matters rather than equality in outcomes.

Broadening out the leadership pipeline. There has been a sharp rise in the share of women sitting on company boards, especially in Europe, where this metric has been a particular focus. The change has been dramatic in one generation, and we think it should be applauded. But there has not been a comparable rise in the number of women in other leadership roles: neither further down the business hierarchy at the management level nor further up at the executive director, CFO or CEO level. Focusing too much on one statistic has the advantage of being transparent and easily traceable but it can distort outcomes. We think focusing on broadening the pipeline at all levels is important. The sectors where we think the focus should be greatest are Technology and Financials, as these sectors are lagging both in terms of female representation generally and also at more senior levels. These sectors are also crucial when it comes to financing for women-led businesses and the implications of AI on work patterns for both men and women.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.